In the October 2019 Monthly Update from GMT Games a new and very interesting looking Card Driven Game was announced called The Weimar Republic designed by Gunnar Holmbäck. The game covers the Interwar Years between 1919-1933 and represents all of the different fighting factions trying to gain control in Germany’s regions and major cities, to maneuver the political landscape of the Republic, and to dominate through a combination of propaganda, parliamentary elections, street violence, economic influence, and ideological zeal. This situation sets itself up perfectly for a game to explore the various parties involved.

We reached out to Gunnar, who is a first time designer, to see if he could give us some insight into the game and how it tells the story of this turbulent time in Germany’s history.

Grant: First off Gunnar please tell us a little about yourself. What are your hobbies? What’s your day job?

Gunnar: I’m a skipper – I drive boats for a living. But I’ve always been a history nerd (I also have a Master’s degree in History) and a gamer, so it should perhaps come as no surprise that historical board gaming is one of my main hobby interests. I’m also very much an outdoors person, spending a lot of time in the woods trying to hone my bushcraft skills. I enjoy that a lot partly because, just like game design, it’s a learning process where you never really reach perfection.

Grant: What motivated you to break into game design? What have you enjoyed most about the experience thus far?

Gunnar: When I was “just” playing games I was always thinking about how they were designed; how seemingly simple tweaks to mechanics can solve difficult design dilemmas, how certain historical situations should be represented, etc., and I always wanted to play a heavier, more in-depth game about the Weimar Republic. No such game existed at that time, at least not that I was aware of. After a while I just came to a point when I decided to make that game myself. Of course I had no idea of what I was getting into, but I liked the challenge.

What I’ve enjoyed the most is probably the creative brainstorming at the beginning of the design process, when you’re not limited by the decisions you’ve already made and the game exists as much in your head as in physical form. The more complete the actual game is, designing becomes less a matter of creative freedom and more a matter of “killing your darlings” and re-working, tweaking, proofing and editing stuff on a more and more detailed level. But seeing all your hard work bear fruit is also very rewarding of course.

Grant: What is your design philosophy?

Gunnar: The general aim of The Weimar Republic is to make people reflect on this complex and difficult historical period, while also enjoying the game as a game. I guess it’s a classic design dilemma – to strike a balance between historical accuracy and playability – but since my game is about such a dire and ominous subject, I feel it’s extra important that the player experience doesn’t veer to much in any of those directions; the game should be enjoyable simply as a game and not just as a history lesson, but at the same time it shouldn’t necessarily be “fun” in a light-hearted or shallow sense.

Grant: What do you find most challenging about the design process? What do you feel you do really well?

Gunnar: Trying to create an asymmetrical multiplayer political game without building on an existing system has certainly proven to be a challenge, especially as a new designer. But the main conundrum is probably the one I outlined in my answer to the previous question: how to tackle a subject that many people find very uncomfortable, using it to make a game that many people (hopefully) will find enjoyable.

One thing I enjoy doing, and also succeed at from time to time I think, is “boiling down history”; immersing myself in detailed descriptions of complex historical processes and then reducing (or abstracting) them to a single card event or a game mechanic that mostly amounts to placing, moving or removing a wooden block or a cardboard counter. I like trying to capture the essence of things, but of course the result is always imperfect in some way.

Grant: What caused you to want to design a game around the history of the Weimar Republic?

Gunnar: It’s a fascinating period that is well suited for the board game medium, so I was actually quite surprised when I couldn’t find any recently published title that dealt with it. It’s also a very important period in European history for obvious reasons, so why not make a board game about it?

Grant: What from this history did you want to model in the game?

Gunnar: Mainly the struggle between democracy and totalitarianism, and how the same historical context could provide fertile ground for political ideals that were so extremely opposed to each other. I wanted to examine the frailty of the democratic system, but also how it managed to survive for so long through such severe hardships. That’s actually an interesting thing about the Weimar Republic – it’s easy to say that it was an experiment in democracy that was bound to fail, but then you haven’t taken into account how resilient it actually was to both right-wing and left-wing attacks. If the Weimar Republic was bound to fail it would have failed during the turmoil in 1919/1920 and that would have been the end of it. But it endured for 15 years and it was democracy itself, not revolution or civil war, that finally spelled its end.

Grant: The game is a Card Driven Game. How do you feel this mechanic helps to tell this story?

Gunnar: I’ve always loved CDG’s because I’m a sucker for narrative and role playing, and CDG’s lets you tell a compelling story based on historical events. I also think that a card-driven system allows you to explore all the “what-ifs” of history in a tangible and visual way that I personally enjoy. It’s always a kick drawing a hand of cards and seeing which weird combinations of historically very separate events you can pull off during a particular session. In The Weimar Republic I’ve enhanced this aspect (but also restrained its potential unhistorical craziness a bit) by making a number of cards dependent on each other; you can play them for points but the events don’t trigger unless a prerequisite card has been played. These “chains of events” are usually short but some, especially during the later stages of the game, can consist of three or four cards. This can create interesting situations game-wise, but of course it’s also intended to reflect the way that some crucial situations with severe consequences could have been avoided.

Grant: What are the factions involved and what special powers and weaknesses do they bring to bear on the struggle?

Gunnar: There are four factions in the game: the Democratic Coalition, the KPD, the NSDAP and the Radical Conservatives.

The Coalition consists of three parties (whose internal relationship is modeled by a Unity track) and represents the German government. Initially it has strong public support, but its influence will inevitably be eaten away by radical forces and it has to fight hard to defend its positions. The unstable economy and questionable loyalty of the armed forces – most notably the infamous Freikorps – doesn’t make the struggle any easier. The Coalition can win either by soldiering through to the end of 1933 or implementing enough Reforms to transform Germany into a functioning liberal welfare state.

The KPD (Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands), the Moscow-aligned Communist Party, has the straighforward aim of transforming Germany into a Soviet-style Dictatorship of the Proletariat. This can be achieved through democratic elections or through a violent revolution, depending on which general strategy the KPD player chooses to follow. The KPD can instigate Strikes and Uprisings and takes the fight to the streets with their Worker Militia units.

The NSDAP (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei) is Hitler’s National Socialists, initially just a splinter faction of the much larger Radical Conservative movement (actually the minuscule embryo of NSDAP was still a Bavarian extremist group called DAP in 1919, when the game begins). Much like the KPD, NSDAP can choose to go for a revolutionary or a democratic stance, each of which makes different tools available; among those are political murder sprees and stealing Mittelstand sympathies from the Radical Conservatives faction.

The Radical Conservatives is not a political party or organization, but a heterogeneous movement consisting of the old élites – i.e. those who used to call the shots before the 1918 November Revolution: military officers, wealthy landowners, businessmen, white collar workers, etc. They are united by their burning hatred for “decadent” modern values, democracy and the Treaty of Versailles, and have strong ties to the army, the Freikorps and big business, which make them an elusive yet very tangible threat to the fledgling Republic.

The factions are asymmetrical, yet several of their abilities overlap and their playstyles can be both similar and markedly different. For example, both the Coalition and the Radical Conservatives can use economic Leverage and both the KPD and the NSDAP can place Cadres (securing a foothold in a given region); yet due to the differing aims of each faction and how their other abilities interact, when and how these tools are used may vary considerably.

Grant: How much opportunity for diplomacy and betrayal exist between the factions? Are some better able to coexist and work together than others?

Gunnar: It’s a dog-eat-dog environment for sure. There is ample opportunity for temporary alliances and the making and breaking of deals. We have not formalized this much in the rules, so players can chose the level of diplomatic play themselves, but we do have some features that open up for interesting potential partnerships – for example certain situations allow the use of another faction’s units in Assaults, and the Radical Conservative has the ability to either mess with or improve the economic situation (which in turn influences a lot of what both the Coalition and the extremist parties can do).

The factions tie into each other along a left-right axis where the Coalition and the KPD are a bit closer connected (for example, the Coalition can neutralize Strikes with economic Leverage) and of course the NSDAP and the Radical Conservatives have a parasitical relationship throughout the game – the Nazis need to steal reactionary Middle Class Sympathies, and the Radicals can usurp an NSDAP electoral victory.

Grant: How do you tell the story of this German history in the fabric of a playable game? What mechanics are used to demonstrate the history and allow players to possible change that history?

Gunnar: To be playable at all, any game based on historical facts needs to simplify complex phenomena, sometimes in pretty harsh ways. The Weimar Republic abstracts all the dynamic interchanges of interwar German politics into four playable factions (a gross simplification of course), an Economy Track ranging from Hyperinflation to Mass Unemployment (another simplification), and a Progress/Reaction Track that reflects the constant struggle between progressive and reactionary ideals that defined much of this period (perhaps the harshest simplification of them all). There are also tracks that represent US and USSR Deals, extremist Stances, each factions’ current political influence, and a few more things.

The three Event Card decks present key figures and events and also provide the Action Points that players use to conduct Actions during the game’s three Eras: Crisis (1919-1923), Golden Twenties (1924-1929) and Decline (1930-1933). Each deck is unique and cards are not carried over from one Era to the next. This obviously makes the game flow in a certain direction because events can only happen during the general time frame in which they happened historically, but it doesn’t make it deterministic; players still have plenty of room to change the course of history and create some wonderfully weird “what if” situations.

Grant: What does the strategic placement of influence cubes on the map open up for players to do?

Gunnar: Having one or more Influence Cubes in a map space gives you Presence in that space, allowing you to place more of your own Cubes, or remove opponent Cubes, in that or adjacent spaces. Having the most Influence in a space gives you Dominance there, which in turn allows you to e.g. Muster units, place Leverage and Cadres, and several other things. Having the most Influence in a Region (a given group of spaces, e.g. Prussia) during a Regional Election gives you Parliamentary Control in that Region, which provides all the benefits of Dominance plus extra benefits like DRM’s in Assaults and that Region’s Parliamentary Control Card, which can be used for several effects.

Grant: How do you hold elections in the game and how are they influenced and ultimately decided?

Gunnar: Each Era has a number of Election Cards (based on the historical number of Elections) that are shuffled into the Event Card decks. When an Election Card is played, both a Regional and a General Election is held at the end of that round. Election scoring is based on players’ Dominance over spaces and Regions, with modifiers such as Middle Class Sympathies, Cadres, military Supremacy, etc. Regional Elections gives Parliamentary Control over the game’s Regions (see previous question), while a General Election can potentially end the game – if anyone but the Coalition wins a General Election, that player also immediately wins the game.

Grant: What role do strikes, violent coups and street fighting play in the influence game?

Gunnar: Strikes have several uses, but their main purpose is to lay the foundation for a Communist Revolution. When a Strike counter is flipped it becomes an Uprising, and when there are four Uprisings on the map and the KPD manages to place a Revolution counter on the Timeline, the KPD player wins the game. This is one of two ways that the KPD can win (the other being through a General Election), and both the NSDAP and the Radical Conservatives have similar victory conditions – either go the parliamentary route or seize power the violent way.

As for street fighting, that’s actually an area we’re currently reworking. A design dilemma that I’ve struggled with from the start is that a game about the Weimar Republic should not be a wargame in the classic sense (i.e. mainly or only about combat), yet must incorporate violent confrontations that range from full military intervention on an almost civil war-like level to riots and pub brawls. Combat and units should be important, yet not be the most important part of the game. One way I’ve approached this is to make players pay a political price for instigating violence; if you Assault someone you’ll lose some Influence in that space regardless of whether you win or lose (winning lets you remove opponent Units and Influence and also Strikes and Uprisings).

While this makes historical sense, it has led to a situation where players rarely engage in combat because they don’t want to risk paying that price. So what I’ve done now is made Unit presence much more important: if you have more Units than anyone else in a space you have Supremacy there, which has several positive effects and also weighs in when determining Election results and even some VC’s. This has created a more tense situation where players will need to build up their Unit presence in key areas and also inevitably fight it out sooner or later, and that’s exactly the type of “gathering storm” feeling I’m after. Escalating tension and the ever-present threat of violence was an important part of the Republic’s political landscape.

Grant: Can you please show us the playtest map and explain what the significance of the various regions shown are?

Gunnar: The map contains 26 Spaces. A Space can be either a State (yellow, orange or khaki rectangle), a Prussian Province (blue rectangle), or a City (circle). All Spaces except Bayern and cities are grouped into Regions: Northern States, Southern States, and Preußen. Spaces in the same Region share a color.

Spaces connected with lines are adjacent to each other. Spaces that are overlapped by a City are adjacent to that City and to all other Spaces overlapped by that City.

All Spaces have a Population Number and a Political Value. The Population Number represents a Space’s Population, and limits the number of Influence cubes that a Space can hold. A Space’s Political Value represents the parliamentary significance of the Space as well as its position in Weimar politics and economics, and is counted during Elections.

Grant: What role does momentum play?

Gunnar: Momentum is an initiative system (the Momentum Player decides turn order for each year), but it also provides important bonuses, e.g. in Elections, and it’s important in many Events.

How do US deals effect the game and what from history does this represent?

Gunnar: US Deals are crucial for the Coalition, as they make Leverage available. Leverage is used to raise the Progression Level, implement Reforms, and neutralize Strikes, among other things. However, when the Great Depression hits a high dependence on US loans it will create severe problems for Germany (which happened historically). This is represented by the Dollar Dependence counters, which accumulate as the number of US Deals increase. The more Dollar Dependence, the higher Unemployment will be at the start of the Decline Era which starts in 1930.

Grant: How are cards used in the design? I see that cards contain both action points and events. How does a player use these cards?

Gunnar: You draw a hand of cards for each Era and use their AP to conduct Actions. You don’t chose between AP and Event; when you play an Event Card the Event always takes place, unless there are some requirements that aren’t met. You don’t need to play a card every turn – in fact you can’t, as there are fewer cards in a hand than turns in an Era and you may only play one Event Card per turn. However, you always have a basic 1 AP that may be used by itself or in combination with any Event Card played, so during some turns you will be using only that basic point. You can also pass which allows you to discard a card and draw a new one.

Grant: I also see where some of the cards are a chain of events that work together. How does this work and can you show us an example of a few of these cards?

Gunnar: I’ve already mentioned this in relation to an earlier question, but I’ll elaborate and give an example from the Decline Era (1930-1933): Heinrich Brüning is a Mandatory Card which means that it cannot be discarded or kept. Besides having some severe Event effects, it also allows play of the Grossraum card, the SA Banned card and the von Papen Appointed card. The latter allows play of the Preussenschlag card and the von Schleicher Appointed card. To make things even more interesting, von Papen cancels the Brüning card, so if it’s played before Grossraum or SA Banned those events will not take place. And von Schleicher cancels von Papen so Preussenschlag is moot unless played before von Schleicher.

This of course models the fact that Heinrich Brüning became a very unpopular Chancellor because of his aggressive yet ineffective measures to combat the Depression. When he was forced out of office, conservative politician von Papen seized the opportunity and tried to use Hitler’s rising popularity to his own advantage but failed miserably, in turn opening up for his closest rival von Schleicher, who made the situation even worse. Each of these steps towards Hitler actually seizing power led to the other, and had any one of them not taken place (or taken place at a later point in time) things could have turned out quite differently. Within the abstracted and simplified context of a board game, these interwoven cards can create some pretty interesting situations game-wise but also make players reflect on how key points in history usually are results of pretty complex chains of events.

Grant: How did you model the instability of the economic and political instability of the time?

Gunnar: The Economy Track is a core aspect of the game. It ranges from Hyperinflation to Mass Unemployment, and has a very tangible impact on gameplay because a rising inflation makes it more expensive for the Coalition to place Influence (reflecting the general public’s distrust in the government), while high unemployment lets KPD and NSDAP place more Influence (representing mainly the working classes turning to the radical parties). The Economy Track also contains Middle Class Sympathies that can be grabbed by either the Coalition (if the Track is at Stable) or by the Radical Conservatives (if it’s at either extreme). The Economy automatically moves towards Hyperinflation during the Crisis Era (1919-1923) and towards Mass Unemployment during the Decline Era (1930-1933), but both the Coalition and the Radical Conservatives can influence it by placing Leverage. This of course opens up for some interesting diplomatic situation between those two factions.

Gunnar: The Economy Track is a core aspect of the game. It ranges from Hyperinflation to Mass Unemployment, and has a very tangible impact on gameplay because a rising inflation makes it more expensive for the Coalition to place Influence (reflecting the general public’s distrust in the government), while high unemployment lets KPD and NSDAP place more Influence (representing mainly the working classes turning to the radical parties). The Economy Track also contains Middle Class Sympathies that can be grabbed by either the Coalition (if the Track is at Stable) or by the Radical Conservatives (if it’s at either extreme). The Economy automatically moves towards Hyperinflation during the Crisis Era (1919-1923) and towards Mass Unemployment during the Decline Era (1930-1933), but both the Coalition and the Radical Conservatives can influence it by placing Leverage. This of course opens up for some interesting diplomatic situation between those two factions.

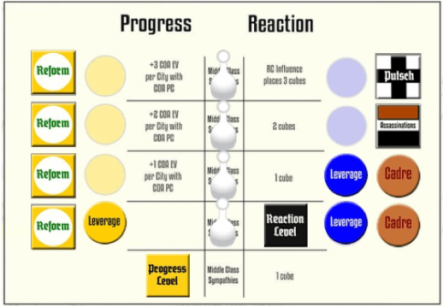

As for political instability, that’s what the game is all about! Player Actions and Event Cards create a shifting and unpredictable environment where most plans are bound to change. The constant struggle between progressive and reactionary ideals are modeled by the Progress/Reaction Track, on which the Coalition and the Radical Conservatives place Leverage to increase Progress and Reaction, respectively. More progressive Reforms are made available as the Progress Level rises, while a high Reaction Level gives both the Radical Conservatives and the NSDAP access to Assassinations, Cadres and the Black Putsch counter which is required for the Radcial Conservative sudden death victory.

As for political instability, that’s what the game is all about! Player Actions and Event Cards create a shifting and unpredictable environment where most plans are bound to change. The constant struggle between progressive and reactionary ideals are modeled by the Progress/Reaction Track, on which the Coalition and the Radical Conservatives place Leverage to increase Progress and Reaction, respectively. More progressive Reforms are made available as the Progress Level rises, while a high Reaction Level gives both the Radical Conservatives and the NSDAP access to Assassinations, Cadres and the Black Putsch counter which is required for the Radcial Conservative sudden death victory.

Grant: How did you abstract the combat system? Why was this your chosen way to represent this aspect?

Gunnar: As I mentioned earlier, a dilemma with this subject is that violence was very prevalent historically, yet the main focus of a game about the Weimar Republic should not be military operations. Consequently, the combat system needs to capture the essence of how violence shaped the political realities of the Republic, without getting bogged down in too much detail.

The system itself is a basic “roll below” variant: all units have a Survival Value which represents their prowess in combat. When conducting Assaults, both sides add up the combined Survival Values of their units and then roll a D6 with the aim of rolling as low as possible. Factors like Parliamentary Control, Strikes, Uprisings, and Middle Class Sympathies provide DRM’s.

I feel that this system, especially in combination with the concept of Supremacy and the political price the attacker always has to pay, provides reasonable realism and a decent amount of tactical depth without overshadowing the political focus of the game.

Grant: I understand the design rewards offensive and aggressive play. Why is this the case and how do players get aggressive?

Gunnar: The Weimar Republic was a chaotic and unpredictable period where the political landscape shifted constantly and dramatically. To model this the game is built around offensive play, but this isn’t necessarily a matter of violently attacking everybody all the time. Rather, it means taking risks, grabbing opportunities, utilizing opponent rivalry to your advantage, and of course stabbing people in the back when you get the chance. To be successful you either act before your opponents force you to react, or force your opponents to act in ways that allow you to react in a way that is favorable to you. Needless to say, this requires good timing and a developed sense for when the circumstances favor a given approach. There are multiple layers to how the factions, Events and Actions interact.

Mechanics like Momentum and Supremacy, as well as the Economy Track and the “sudden death” victory conditions all contribute to this. To get the Events on the table and make players use all their AP’s, there’s a penalty for holding cards at the end of the Era.

Grant: What are the victory conditions for the game?

Gunnar: Each faction can win in two ways: the Coalition either stays in power until the end of 1933, or implements a Reformation, which is a remodeling of German society into a functioning liberal welfare state. This requires both a number of Reforms on the board and the absence of too much opponent Supremacy. The KPD and the NSDAP win either by scoring highest in a General Election, or by launching a successful violent power grab (Revolution or Putsch). The latter approach requires a number of Uprisings in KPD’s case and Supremacy in key cities plus Middle Class Sympathies for the NSDAP. The Radical Conservatives can also launch a Putsch to win, which has requirements similar to the NSDAP’s Putsch, or win by usurping an NSDAP electoral victory. This is meant to reflect the fact that the far Right’s strategy during the decline of the Republic was to use Hitler’s exploding popular support to secure their own position, something that of course failed historically but could have been successful given the right circumstances.

Grant: What scenarios are included in the design?

Gunnar: There are 4 scenarios included as of now: the full campaign (1919-1933), a shorter “tournament” scenario modeling the final years of the Republic, a very short tutorial scenario with simplified rules that focus on just a few years at the end of the Crisis Era, and a medium-length scenario with the full rules that is suitable as a follow-up to the tutorial scenario when players feel ready for the “real” game.

Grant: I understand there is a solo bot. How does this work? What does the bot do well?

Gunnar: This is still very much a WIP and we are not really ready to reveal much about it, but suffice to say that the solo system will be in the line with recent GMT developments, i.e. we’ll keep it simple and focus on cards rather than detailed flowcharts. Developer Jason Carr is working on several other GMT projects involving solo systems and there have been some very interesting innovations on that front lately, so there’s no shortage of ideas and inspiration. Our intention is to have bots for all factions, so you can play the game solo or with one, two, or three human opponents and with any combination of factions.

Grant: What are you most proud of with the design?

Gunnar: I’m pretty happy with how the game captures the “Weimar feeling” that I was after when I first started the design. I think the mechanics, the factions and the events combine to tell a compelling story about this fascinating period. I like how we’ve streamlined the game during the development process and yet retained the core systems and the asymmetry of the factions. Much credit goes to Jason, as he’s really helped me understand the need to assassinate my darlings over and over again (they have a tendency to rise from the dead sometimes).

Grant: What other games are you working on or what games are you considering?

Gunnar: I’ve got several projects lined up, one of which is pretty far along in the conceptual stage and has seen quite a lot of private testing. As soon as TWR moves into art department I’ll focus on getting an official prototype ready for that and pitch it to a publisher. Not quite ready to talk about it in any great detail but it’s a modern-era geopolitical conflict simulation game for two players, featuring a considerable level of bluff and deduction. I’m also outlining a 4X game set in a premodern era, and a solo ancients game that’s been in the back of my head for many years and that I’ve finally managed to zoom in on a bit more. We’ll see what happens. Right now my main focus in getting TWR ready for publication and making sure that it’s as good as it can possibly be when it finally hits gaming tables.

I want to say thank you to you for your willingness to answer my questions and give such thorough and well thought out answers that help us get a great visual of the game. I personally love the idea of this game and cannot wait to get 3 friends together to try it out. We love lots of player interaction and back and forth and this appears to have all of those elements plus so much more.

If you are interested in The Weimar Republic, you can pre-order a copy for $55.00 from the GMT Games website at the following link: https://www.gmtgames.com/p-841-the-weimar-republic.aspx

-Grant

I became engrossed in this time period between the wars in Germany when I began research for a novel I am currently writing. Naturally, this game caught my eye. Thanks for the detailed discussion on how this game came to be and on its general design. Given the backlog of GMT games, I will waiting for some time for this one to come out.

LikeLiked by 1 person