With this My Favorite Wargame Cards Series, I hope to take a look at a specific card from the various wargames that I have played and share how it is used in the game. I am not a strategist and frankly I am not that good at games but I do understand how things should work and be used in games. With that being said, here is the next entry in this series.

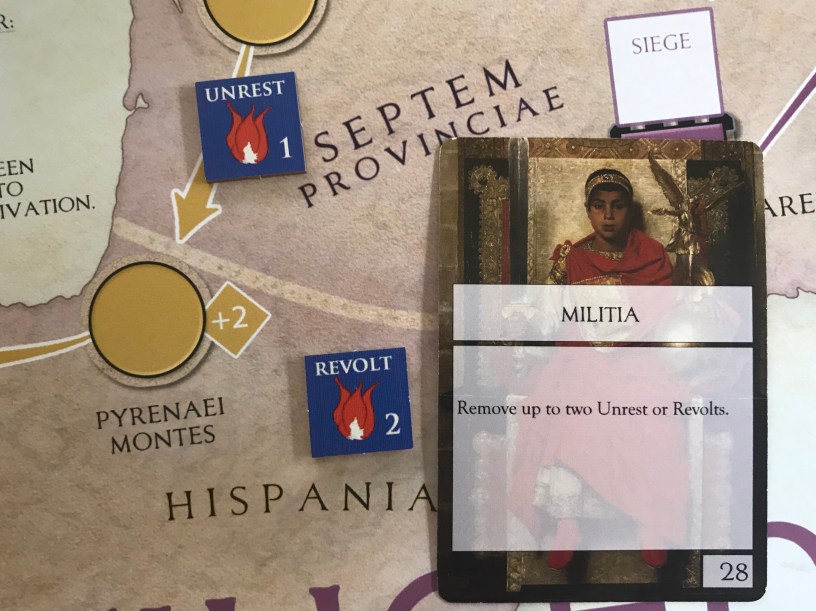

#63: Militia from Stilicho: Last of the Romans from Hollandspiele

Stilicho: Last of the Romans is a very well designed and interesting solo experience that plays in 60-90 minutes. But, due to the unforgiving nature of the random card draws and its reliance on dice luck, that admittedly can be mitigated through cagey card play and proper decisions, the game can be over very quickly. In fact, my very first play a few years ago lasted only 2 rounds and was over in about 15 minutes. Remember that the historical Stilicho only made it to Round 3! The cards are at the heart of the game here and make it a very tense and decision filled experience. Having to analyze each card, measuring its utility against the board state and what pressing matters the player must address while also fretting over having to discard a good Event Card that just isn’t useful at this point in time to take an action can be really agonizing. I think that this design works even better than its predecessor Wars of Marcus Aurelius.

The cards are a form of multi-use cards, as most Card Driven Games are, as they can either be used for the printed events on the cards or simply to be discarded to take one of a number of actions available to the player. It is important to read every aspect of the card thoroughly as some cards have multiple effects, differing effects depending on what the state of the game is or whether one Barbarian has surrendered or may have several prerequisites to that card being allowed to be played.

There are some events that are too important to your efforts to ever discard to take an action as they provide you with such great benefit and are more efficient than taking individual actions. Don’t get me wrong though the playability of a card is always dependent on when in the course of the game the card is drawn. An example of what I am talking about is the Militia Roman Card.

During the game, some cards will cause Unrest Markers to be placed on the various tracks that wind their way through the provinces. These Unrest Markers represent the erosion and weakening of Roman control, the spread of fear throughout the populace due to the threat of usurpers and ultimate civil war as well as the logistical difficulties of defending against barbarian incursions. They act as a critical, accumulating threat that, if left unchecked, can lead to widespread revolts, which are one of the primary ways a player loses the game. Unrest Markers are placed in Dioceses when specific enemy cards (particularly the Vandals) are activated or reach the end of their movement tracks. If a Diocese already contains an Unrest Marker when a new one is triggered, it indicates increasing instability, requiring the player to flip an existing, lower-level Unrest Marker to its “Revolt” side. Unrest/Revolt Markers increase the difficulty of battles in that province. When attacking or defending in a affected Diocese, the marker adds to the enemy’s strength. Also, a major loss condition in the game is having too many Revolt Markers on the board simultaneously. Managing and removing these markers is essential for survival. Unrest Markers are placed in a specific order across the board—starting from Hispania and moving through Gallia to Italia—which dictates the geographic spread of the crisis. Players must spend valuable actions (usually by discarding cards) or use specific Event Cards such as the Militia card to remove these counters from the board.

Before the late 2nd century BC, Rome used a citizen militia or levy of property-owning men aged 16–46, serving unpaid during summer campaigns. Organized by wealth, they formed three lines—hastati, principes, triarii—and provided their own equipment. They were crucial for seasonal defense and expansion, as well as for patrolling and safeguarding supply lines, trade routes and newly conquered territories, ultimately transitioning to a professional army after 107 BC. The citizen troops were grouped into maniples based on age and wealth, with the poorest acting as light-armed skirmishers (velites). Service was typically restricted to the annual campaign season, often ending with the Festival of the October Horse on 19 October. The militia employed a three-line, checkerboard formation to allow for tactical flexibility. Due to many reasons, the militia system was phased out after 107 BC in favor of a full-time, professional army, although conscription remained as a, mostly unpopular, option for raising forces.

I wrote a series of Action Points on the various aspects of the game and you can read those at the following links:

Action Point 1 – the Mapsheet focusing on the three Fronts down which your enemies advance, but also covering the different spaces and boxes that effect play such as the Olympius Track, Game Turn Track, Army Box, Leader Box and Recovery Box

Action Point 2 – look at the cards that drive the game and examine the makeup of both the Enemy Deck and the Roman Deck.

Action Point 3 – look into the Roman Phase and examine how cards are discarded to take one of nine different actions.

Action Point 4 – look at a few examples of Battles and how they are resolved.

Action Point 5 – look at a few points of strategy that will help you do better in the game.

I shot a playthrough video for the game and you can watch that at the following link:

I also followed that up with a full video review sharing my thoughts:

In the next entry in this series, we will take a look at Guns of August from Paths of Glory: The First World War, 1914-1918 from GMT Games.

-Grant