We love interacting with new designers on our social media platforms and getting a feel for their upcoming games. Over the past couple of years, we have posted a few interviews with a new designer named Joe Schmidt and I have really enjoyed his insights about these games which cover such very cool historical happenings such as Guerrillas of the Peninsular War, This Present Winter: Washington’s Crossing and the Battle of Trenton, Anzac Cove and Kettle Hill: The Battle for San Juan Heights. He also is on the design team for the very cool looking In the Shadows: French Resistance 1943-1944 from GMT Games and it has been very cool to see him grow and stretch himself as he is becoming his own designer. Last year, his newest design was announced as a part of the GMT Games Monthly Update which is an entry into the fast expanding and ever more popular Levy & Campaign Series. His entry is the fifth in the series and focuses on Henry and the drama of the famous Agincourt campaign.

*Note: The pictures and game art used in this interview, and pictures showing any of the various components are still in design and are intended to be illustrative at this point. Also remember that rules might still change prior to final development and publication.

Grant: What is the history behind your new Henry: The Agincourt Campaign, 1415?

Joe: Henry tells the story of the eponymous King Henry V of England and his campaign into Northern France in the Fall of 1415. Part of what is known as the Hundred Years War, it is most famous for its culmination in the Battle of Agincourt and the myths and legends that it created. I would assume that most of the readers have heard of Agincourt before, as it has been an important part of English culture for many centuries now.

I find the most fascinating part of the history of the Agincourt Campaign to be the historiography, or the study of the study of history. Just take a moment and think about the first time you learned about Agincourt. What was the story you were told? Was it about a small band of brothers against a massive army of one hundred thousand evil French knights? Was it a patriotic story about the power of the common yeoman archer? Or, was it something much more real?

Our modern historical understanding of the campaign is very different from the story that Shakespeare tells. King Henry V sailed with an army of around 11,000 professional warriors from Southampton to Harfleur. After an extended and costly siege, Henry sent home his sick soldiers and marched an army of around 7,000 across the Somme towards Calais. On the way, they were intercepted by a disorganized French army of less than 15,000 in the muddy fields of Agincourt. This is the history that the game models. Less mythical, but still an epic tale.

Grant: Why does this conflict fit the Levy & Campaign Series parameters?

Joe: For me a Levy & Campaign game should have two main areas of focus; to show the logistics of medieval warfare and to share a compelling and interactive historical narrative.

Henry allows the players to experience the logistical puzzle of invasion during the early 15th century as both the attacker and the defender. The English player will need to plan for the logistical challenge of a war fought on foreign soil. The French player must react to the invasion by mustering a defensive force in an incredibly tenuous political environment. Both players are left with an experience that uses the modern historiography of the campaign in order to provide an accurate and enjoyable gaming experience.

Grant: What needed to change in the system to properly tell the story of the Agincourt campaign?

Joe: The first thing that I needed to change was the time frame. The rest of the Levy & Campaign Series operates on a 40-day or longer calendar turn. In this case, the entire campaign lasted less than three months, so I decided to use a 15-day calendar instead. This allowed me to fit a full game into the timeframe while also teaching the calendar system to newer players.

Another change was the Levy Phase. While the English will have a more traditional Levy Phase but only at the beginning of the game, the French will use their Commands to build their armies. It would not have made historical sense to split the game in the usual Levy & Campaign Series way, and we’ve found that the puzzle of mustering a French army while the English are on campaign makes for a really compelling gaming experience.

Grant: What is your overarching design goal for this entry in the Levy & Campaign Series?

Joe: I want players to walk away from Henry having a strong understanding of Levy & Campaign gameplay. When I first played Nevsky my biggest points of confusion were the various actions and supply. The core element of gameplay is managing and collecting provender in order to fuel the operations of your army. Henry creates a streamlined experience that makes these core concepts easier to understand. Every part of the design was a focus on making the system more approachable in order to open up access to this wonderful series.

Grant: I understand this could be used as a gateway to the Levy & Campaign Series. What makes this design more approachable? How have you taken care to simplify and streamline but not dumb down or cheapen the depth of the mechanics?

Joe: This was a major concern for me in the design process. As I mentioned above, I want players to leave the game feeling comfortable enough with the supply and action mechanics that they can move onto any other Levy & Campaign Series game to enjoy the historical narrative that the designer presents. A couple of the key changes were:

- Creating a version of the game that can be played in full in 60 to 90 minutes.

- Limiting the total number of available Lords in order to allow for more focused play.

- Consolidating the Lordship and Command Ratings into one single Command Rating.

- Removing the Battle Board and simplifying the Battle Process.

- Offering a full solo scenario to allow new players to learn the ropes before they play their first two player game.

Now, just because I streamlined the design doesn’t mean it isn’t fun! In fact, I think I was able to push the limits of the system a lot in order to create a really dynamic game about the Agincourt campaign. Huge credit goes to Volko and Christophe for their excellent development work in helping me achieve this balance. Couldn’t have done it without them.

Grant: What elements from the history did you need to include in the design?

Joe: One of the many things I wanted to model were the English Longbowmen. It was important to me that their role in the design was portrayed as accurately as possible. So important that I took up archery as a hobby (which is very fun, by the way). I really wanted to understand more about how the archers fought, and how they should be represented in the game. This, along with the rest of my research, led to an Archer unit I am super proud of.

English Archers were not effective because of their armor piercing abilities. They were effective because of the volume of arrows they fired and their ability to also fight as skirmishers in close combat. Couple that with the fact that a Lord on a budget could get two Archers for the cost of one Man-at-Arms, and it makes perfect sense why the Longbowmen were such a vital part of the English army. I feel that Henry does a great job of modeling this history.

Grant: What sources did you consult and what one must read source would you recommend to anyone wanting to know more?

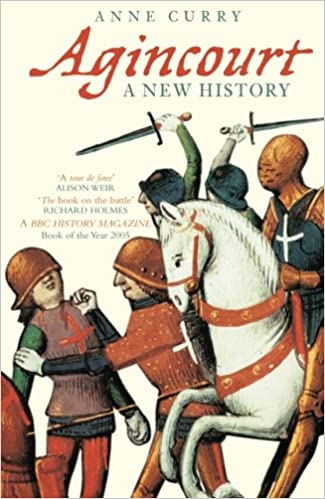

Joe: There are so many sources for the Battle of Agincourt that it can feel a little bit intimidating. But, I also think that in order to have a full understanding of the legend it is important to study various ways the story has been told. And, lucky for us, Professor Anne Curry has made it her life’s work to help us out. I don’t think this game would exist if not for the incredible work that Professor Curry has done.

The Battle of Agincourt: Sources and Interpretations by Curry is a great compendium. This book reviews everything from primary source chronicles to the movie adaptations of Shakespeare’s Henry V. Seeing the development of the myth over time is a good way to understand the history. I also enjoyed an online course of Curry’s called Agincourt 1415: Myth and Reality. This course presents a lot of information that helped in building my model for the game. Also, I would be remiss to not mention the website Medieval Soldier. This site is a treasure trove of indentures and muster rolls from the English army, and was a key to understanding the real numbers of soldiers who were part of the campaign.

If you could only read one book on the subject, I would suggest Agincourt: A New History by (you guessed it) Anne Curry. An exciting read, and a great encapsulation of all of the wonderful work that Curry has added to the historical study of Agincourt over the course of her career.

Grant: What factions are represented in this time period?

Joe: The three factions in Henry are the English, Armagnac French, and the Burgundians. 1415 sees France divided by a bitter conflict between the Armagnacs and the Burgundians as they both position themselves for control over the sickly King Charles VI. This era of French history is dripping with incredible infighting and drama (it would make a really fantastic Netflix show), so modeling this discord is super important to telling an authentic historical story.

Grant: What Lords are available to both sides?

Joe: The English are led by King Henry V and his uncle, Duke Edward of York. The Armagnac French are led by Constable Charles d’Albret, Marshal Boucicaut, and Duke Jean of Alençon. The Burgundians are represented in the game via some interesting limiting mechanics on the Armagnac player and the optional English Lord, Duke Philip of Burgundy.

Grant: How do the French have to deal with their ongoing civil war between the Armagnac and Burgundian factions? Why was this civil war important to model in the game?

Joe: The French forces were hampered by the Armagnac-Burgundian conflict throughout the Agincourt campaign. Add in a lack of leadership from King Charles VI, and it made mounting the defense of Northern France even more difficult. I approached this a couple ways in the design.

Each 15-day Turn the French player will need to include a Forced Pass Card into their Command Deck. This limits their ability to act as quickly as necessary, and gives the English more time to operate as the French muster their forces. This process is also made more difficult by the discord amongst the French nobles.

When the French muster Units and Arts of War Cards they have two options. To spend two Commands to collect the Unit or card they want, or to spend one Command to randomly draw from the French Muster Cup or Arts of War Deck. So, the French player will have to decide whether they want to sacrifice vital time in the field in order to build the army they want to fight with. I’ve found that these changes make for a really compelling puzzle, and model history well.

Grant: How does the English player set their victory conditions based on their choices in building their army at the game’s outset?

Joe: Henry uses Royal Burden to represent the wealth and power the English King needed to use to build his army. At the beginning of several scenarios, the English decide how much Royal Burden to incur in Mustering up their army. As the English levy items, they mark the cost on the Royal Burden Track. In order to win the game, the English must reduce their Royal Burden by conquering strongholds, capturing French Lords, and campaigning through Northern France.

I really enjoy this mechanic for a couple reasons. First, it really models the motivations behind Henry’s campaign. He wanted to prove himself not just as the rightful ruler of France, but also as the legitimate King of England. A couple weeks before the beginning of the siege at Harfleur, Henry was almost killed by some rebel nobles, so his success was vital to his future.

From a gameplay perspective, it adds a really interesting gamble. Can you improve on Henry’s result? Can you lead a different type of army to success in Normandy? All of these opportunities make for a game that offers a lot of replayability and a lot of space to better understand the history of this famous campaign.

Grant: How do the French Nobles start their game?

Joe: One French Lord, the Constable Charles d’Albret, begins on the map at the start of the game. The other two French Lords, Marshal Boucicaut and the Duc de Alençon, begin on the calendar with the ability to be levied during the game. This represents the fact that the French weren’t really ready for the English invasion so the player will need to play catch up. This is also a feature in other games in the series, so serves as an opportunity to teach newer players about this part of the system.

Grant: How has the process of designing a game based on logistics opened new understanding into the legend of this event?

Joe: Oh man, what a question. As I mentioned earlier, the number of soldiers at Agincourt has always been heavily disputed. In designing a logistics game about the campaign, it was easy to see how ridiculous some of these numbers were. Managing an army of even 30,000 people in a game of Henry would be incredibly difficult. But, creating a smaller and more focused army of half that number allows for way more tactical flexibility. It really helped me understand the limitations that a 15th century commander would operate under. It also made it very clear that even though the legends weren’t true, the reality is much more compelling.

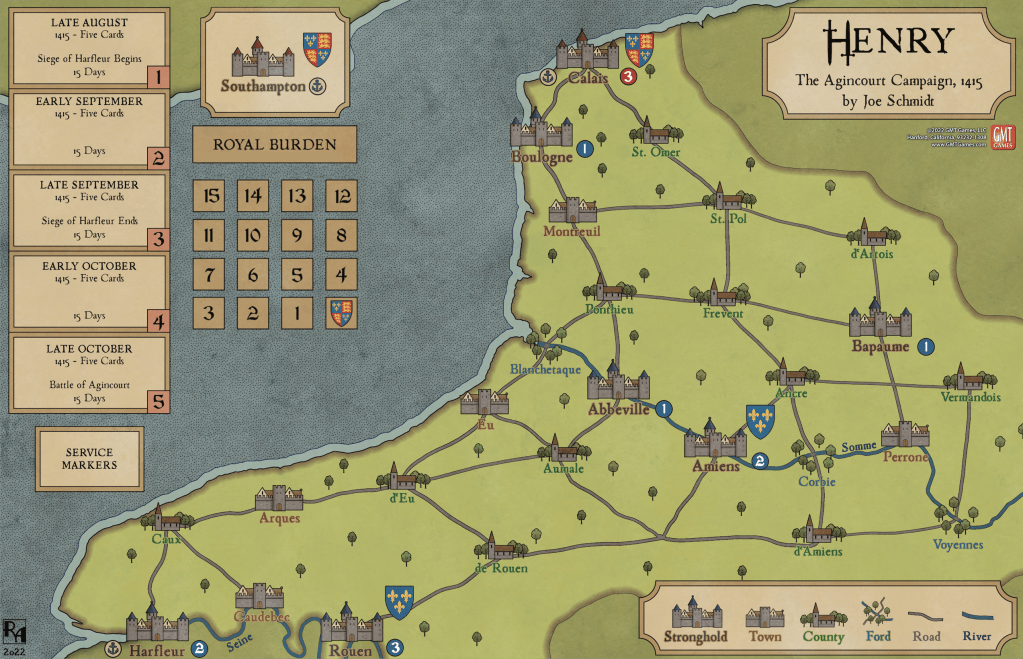

Grant: What area of France does the map cover? What strategic considerations or pinch points are created by the layout of the point to point movement lanes?

Joe: The game uses a point-to-point map of Normandy and Picardy in northern France in 1415. My favorite aspect of the map design was the focus on the importance of the Somme River. Crossing a river with an army is always an arduous and vulnerable task. I had bounced around a lot of ideas on how to incentivize this decision for the English player and the French player. Thanks to my great development team of Christophe and Volko, we ended up with a really cool solution.

The English player can reduce their Royal Burden by 4 if they are able to march from Harfleur to Calais, or vice versa, by crossing the Somme at Strongholds or Fords. Crossing at a Stronghold would force the English to start a Siege and leave them vulnerable to a French attack. So, the best option for the English is to find a Ford to cross. In order to make life more difficult, the French can take a Block Ford action. This puts a small garrison at the Ford that makes crossing at those spots incredibly difficult.

This makes for an interesting race between the English and the French. Can the English get across the Somme before the French are ready? Or, will the French block the fords in order to further dwindle the already meager English supplies. The result makes for fun gameplay and focuses on the historical importance, which is a total home run for me as the designer.

Grant: What types of asymmetry are built into the design and how specifically do the English units differ from those of France?

Joe: The main asymmetry is victory conditions for both factions. The English are the attackers, and must lead a successful campaign in order to win. The French are the defenders, and must rally their forces to defend Northern France. While the nature of the actions taken by both players is very similar, their asymmetric goals make for two very different play experiences. It also serves as a great opportunity for new players to learn different Levy & Campaign strategies to prepare them for other games in the series.

The English and French forces at this time were pretty similar. Retinue and Men-at-Arms units on both sides consisted of well-trained and heavily armored soldiers who predominantly fought on foot. The major difference was the English Longbowmen. The French Militia, representing archers and crossbowmen, were nowhere near as capable or as ubiquitous as the English Archers. To model this, the English Archer unit is less expensive to muster and has a strong Archery Strike in Battle. This helps to show why they were such an essential part of English armies during the Hundred Years War.

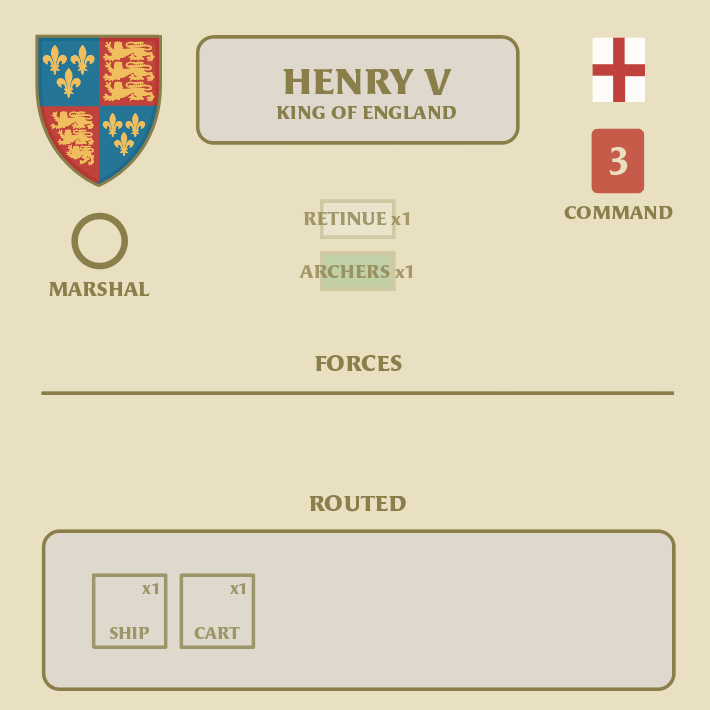

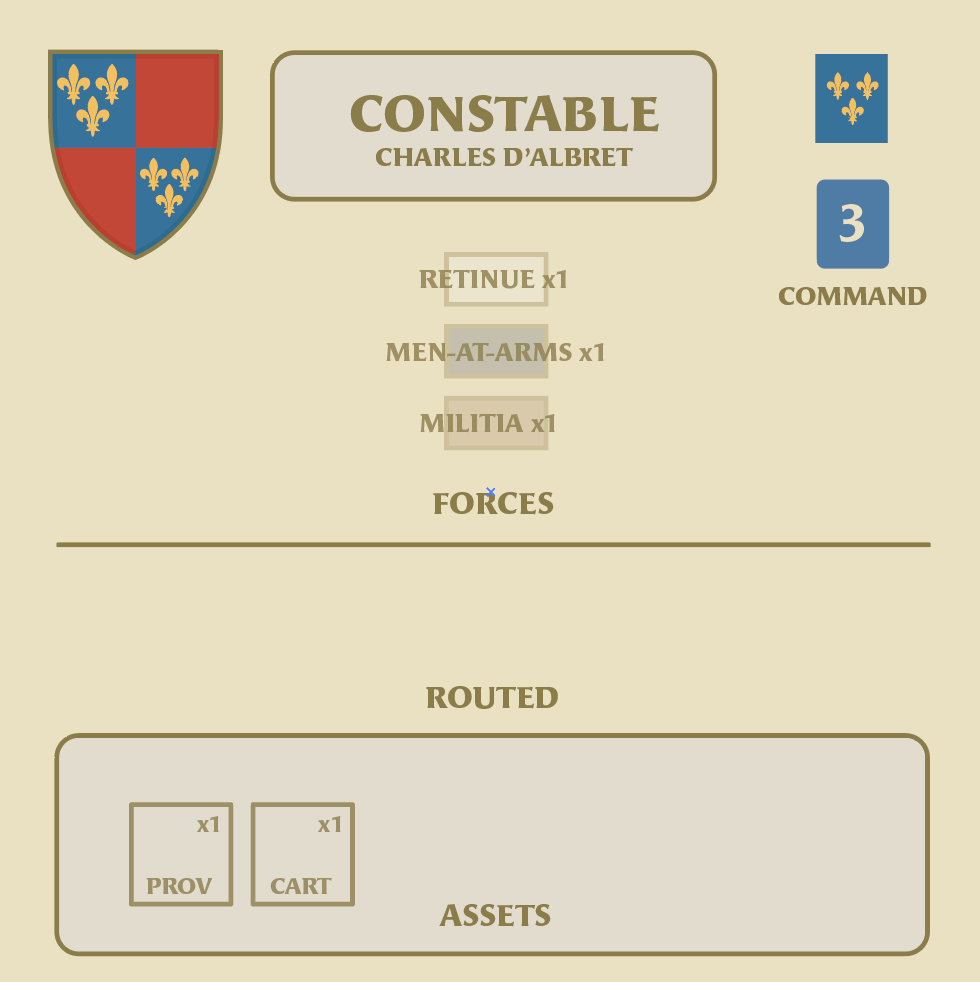

Grant: Can you show us a few of the Lord Mats and explain the different parts?

Joe: Here are the Lord Mats for King Henry V and Constable Charles d’Albret. The Lord’s personal heraldry is in the top left hand corner of the mat. This is used to identify different components in the game as belonging to the Lord. On Henry’s mat below the heraldry you can see a gold ring that reads “Marshal”. This is a special ability that allows the Lord to move multiple friendly Lords with a March action.

In the top right hand corner is a banner, representing the faction, and the Command Rating (more about that below). The rest of the Mat shows the Units and Assets that each Lord starts the game with. The Routed area is used during combat to show units that have failed their Armor range rolls (more about Combat later). I love the Lord Mats in this series because they are such a clever way to represent so much important information.

Grant: What is the Command Rating on the Lord Mats? How do these values compare across the different Lords for both sides?

Joe: The Command Rating of a Lord represents their ability to lead both on and off the battlefield. When a Lord’s Command Card is flipped, they are able to take actions based on their Command Rating. Five of the six Lords have a Rating of 3, which represents their experience and ability as commanders. The sole Lord with a Rating of 2 is Duke Jean of Alençon, which just represents a lack of experience in comparison to the other Lords in the game.

Grant: What role do the cards play in the design?

Joe: Just like the other Levy & Campaign Series games, Henry uses Arts of War and Command Cards. Arts of War Cards add Capabilities that Lords can use to improve their chances of success throughout the game. I like these cards because they offer a lot of variability and replayability. Command Cards are used by the players in a Command Deck to determine the order that Lords will act during the turn. The other card type are Encounter Cards, which are new to the system.

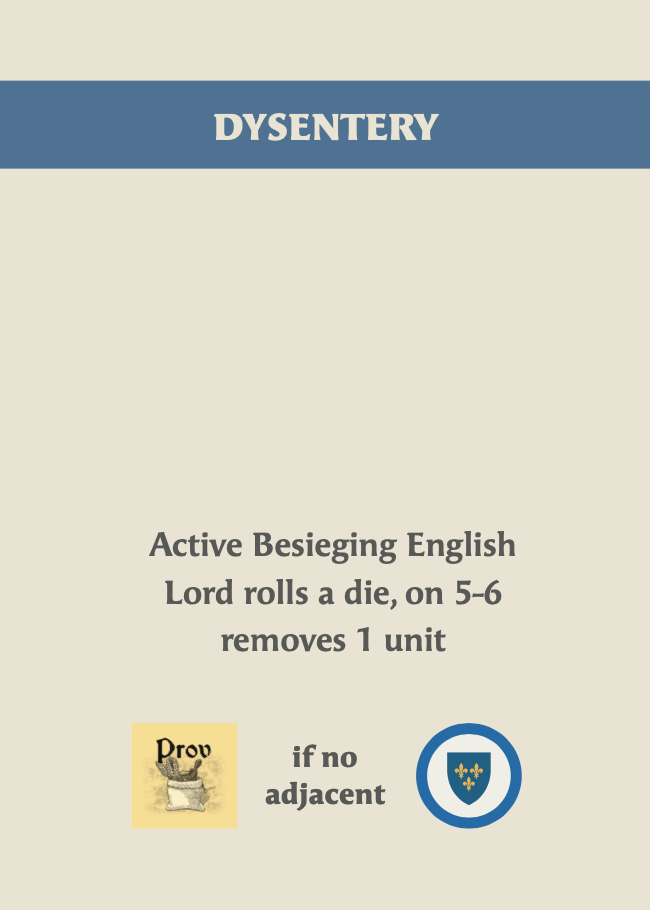

In Henry, the Arts of War Cards don’t have events on them. Instead, the Encounter Deck is used to help add interesting narrative moments to the game. These cards are flipped each time the English player attempts to Forage for Provender to feed their soldiers. While a couple of these cards have events that help out the English player, the majority of them are very bad. From skirmishers to dysentery, the Encounter Cards really help to model the difficulty of campaigning on foreign soil.

Grant: Can you show us some examples of cards and explain how they work?

Joe: These are two of the Encounter Cards that I mentioned above from the game. I like these cards because they model the difficulties of Foraging in enemy territory while also introducing some interesting decision points for the English and some help for the French.

On the left is one of the Dysentery cards. When this card is flipped during a Forage action the English player would collect one Provender, if there was no adjacent French Lord, and roll a die to see if they lose a unit. Dysentery was a huge problem for medieval armies, so it was important that I found a way to model that in the game.

On the right is one of the positive Encounter Cards for the English. When this card is flipped the English would collect one Provender and have the option to take this card out of the Encounter Deck. In a Battle this would add +1 to any Archers Protection in Melee (changing their Armor range to 1 – 3). Now, taking this card out of the Encounter Deck lowers your odds of success during Forage, but the trade off is still pretty good.

Grant: How does combat work? How did you go about deciding to assign relative strengths to different unit types? What is the best unit on the field?

Joe: Medieval battles were a huge gamble. A commander could enter the field with an army that was fully prepared and still suffer a devastating loss. So, the combat in the Levy & Campaign Series is dice based. Units have two Strike Values (Archery and Melee) and an Armor Range. Strikes are automatic, and are resolved based on a unit’s Armor Range. For each Strike you receive you select a unit and roll a die. If the roll is equal to or less than the Armor, you’ve made the save. If it is higher than your Armor Range, then you fail.

For me, the best unit is a tie between the Retinue and the English Archers. Each Lord starts the game with one Retinue with a Melee Strike of 1 and an Armor Range of 1 – 4. These units are great in Battle and also have excellent survivability. The English Archer has a lower Armor Range of 1 – 2, but has an Archery Strike of 1 and you can buy two for one Royal Burden. This makes for a powerful unit that English Lords can use to cheaply fill the ranks of their armies.

Grant: What have been some changes that have come about through the playtest process? What still needs work?

Joe: The playtesting process has been fantastic. I’ve learned so much about designing and modeling in historical design. The game has seen a great deal of evolution since the beginning, and it’s been a really fun challenge. Playtesting is a key part of my design process, so I have a great deal of appreciation for my testers. I’d love to give a shout out to a couple testers.

Stephen Rangazas and Joe Dewhurst played an earlier version of the game and shared some really impactful feedback that helped move things forward. Also wanted to shout out to the Levy & Campaign Discord and designer Jason W. (EPIPOLAE) and his young son. They both had great feedback, but I loved that a parent and their kid played one of my games. I still play games with my Dad, so creating a moment like that was really special for me.

Grant: What are you most pleased about with the design?

Joe: One of the first games I ever designed as a little hex and counter game called St. Crispin’s Day. I did all of the art in Keynote and shared it with everyone. I brought it with me to the San Diego Historicon where I got to meet Volko and show him my game. At that same con, Volko had a really cool prototype of a new game called Nevsky that he was playtesting. It was an awesome trip, and really made me feel like I could be a part of something really special.

Fast forward five years and here I am talking about my very own Levy & Campaign Series game on the Battle of Agincourt. I’m thrilled I’ve gotten to work with and learn from Volko. I’m proud that I have been able to tell this story that means so much to me. And, most of all, I’m so excited to share this game and the amazing Levy & Campaign system with all of you wonderful gamers out there.

Grant: What other games are you currently working on?

Joe: Dan Bullock and I are getting really close to finishing up In the Shadows and sending that over to the art department, so be on the lookout for that. I’ve also been doing work on the solo design for Gunnar Holmbäck’s The Weimar Republic which is in the final stages of development.

I’m also doing development work for Damon Stone’s Ten to One (formerly Liberation – Haiti) about the Haitian Revolution. It’s a really lovely cooperative game about a really important moment in world history, and I feel honored to be a part of it. And, as if I wasn’t doing enough, I’m also working with the wonderful Taylor Shuss on our cooperative game The Sacred Band.

Thanks Joe for the look inside this very cool entry to the Levy & Campaign Series. I can feel your passion for the game and its history and believe that this will shine through in the game play experience as always. Keep up the good work Joe and we look forward to talking with you about your future upcoming game projects.

If you are interested in Henry: The Agincourt Campaign, 1415, you can pre-order a copy for $49.00 on the GMT Games website at the following link: https://www.gmtgames.com/p-975-henry-the-agincourt-campaign-1415.aspx

-Grant

Very nice

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very excited for this one.

LikeLiked by 1 person