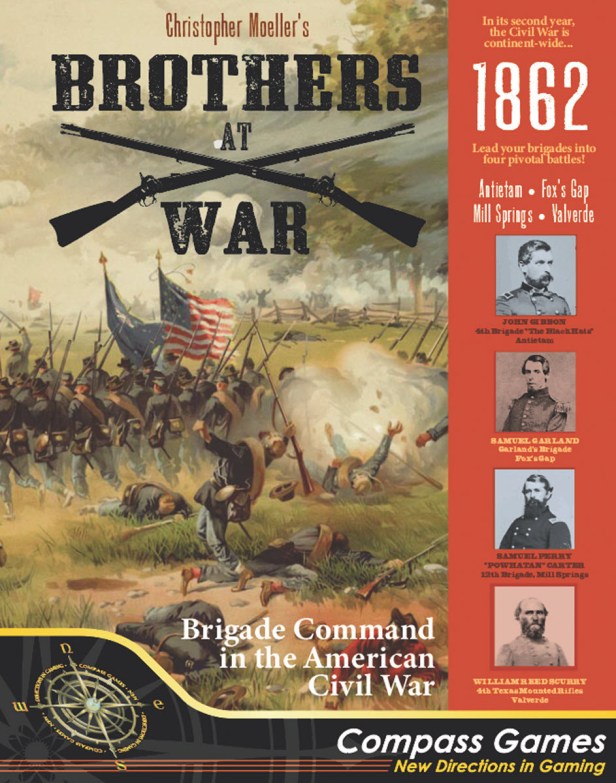

While attending WBC this year in July, we met up with a new designer named Christopher Moeller to take a look at his new game called Brothers at War: 1862 from Compass Games. We were not only impressed with the game but Christopher is an interesting person and really has a lot of good ideas that he is working on and we hope to see many of those on our tables in the near future. After our encounter, we asked if he would be willing to do an interview and he was more than glad to talk with us about the game.

Grant: First off Christopher please tell us a little about yourself. What are your hobbies? What’s your day job?

Christopher: I was an author and illustrator for 30 years: both writing and painting graphic novels (JLA: A League of One, JLA: Cold Steel, The Iron Empires trilogy, Interview with a Vampire, etc…), as cover illustrator (Lucifer, Shadow of the Bat, The Specter), and as an illustrator for most of the big game companies, primarily Wizards of the Coast (Magic the Gathering and Dungeons and Dragons), but also FASA, White Wolf Games, and others.

Grant: What motivated you to break into game design? What have you enjoyed most about the experience thus far?

Christopher: I’ve always loved games (historical wargames in particular, but in no way limited to them). Now that I’m retired, I’ve made game design my new vocation. It’s a total passion. I love losing myself in all the elements of the work…design, testing, art, graphics. I’m teaching myself Adobe Indesign now so that I can do my own rulebooks (the one piece I’m still missing).

Grant: What designers would you say have influenced your style?

Christopher: Kevin Zucker, Frank Chadwick, Mark Walker, Dan Verssen, Ben Hull, Bowen Simmons, I’m sure there are others I’m not remembering…

Grant: What do you find most challenging about the design process? What do you feel you do really well?

Christopher: Well, for starters, I’m no mathematician. I have a friend who checks my numbers for me, and I’m always just amazed at how his mind works. Numbers are just a bunch of mysterious magical symbols to me. On the other hand, I’m no mathematician! So, I don’t suffer the limitations of a logical, structured, procedurally focused mind. I can make intuitive leaps (that comes from painting I believe). I can imagine many different branching design paths and quickly decide which are helpful and which aren’t. It helps me discover alternative, often counter-intuitive solutions to problems.

Grant: What historical event does your new game Brothers at War cover?

Christopher: Brothers at War covers four battles in the year 1862 during the American Civil War. Each battle occurred during an invasion of the north by the Confederacy: the Maryland Campaign, which included the battle of South Mountain and climaxed at Antietam, the confederate invasion of Western Kentucky in January (Battle of Mill Springs), and the invasion of New Mexico by an army out of Texas (Battle of Valverde).

Grant: What was your inspiration for this design? What challenges did you have to overcome?

Christopher: I love to paint landscapes, particularly on battlefields. I set up my easel and my chair and my umbrella and watch the wind in the trees, the clouds going by. I try to imagine what the place must have looked like in the past. I imagine what it would have looked like full of troops and smoke and conflict. That was my inspiration for this design. I wanted that scale… he one I see when I’m painting. Not a satellite view of armies and corps moving over a network of roads, but the woods and slopes and buildings that I see when I’m walking around a battlefield. So, tactical. That was established early, and dictated the brigade as the maneuver unit. There are challenges when dealing with tactical games, ever since Squad Leader opened that door, and they primarily involve detail. How much is enough and how much is too much? Squad Leader has conditioned gamers to expect a high level of detail in tactical games. I wanted a tactical design, but I wanted to lean further towards the low-detail end of the spectrum. I wasn’t sure if that was possible, or if it would be accepted by players who would expect a tactical game to emphasize different weapon types, ammunition consumption, etc…

Grant: What was your overarching design goal?

Christopher: I want all my designs to accomplish two main things. First, I want the game to be fun. Second, I want to be historical (in the broad sense). If a game isn’t fun to play, for me, it sits on my shelf. I want a game that moves quickly, doesn’t have a lot of down time, gets me excited, gives me lots of interesting options to play with, while injecting enough uncertainty to throw off any sort of scripted approach to victory. For historical subjects, a game has to feel grounded in its period. When I play a game that’s too abstract, I don’t learn much, even if the game itself is fun. There’s an educational element that’s important to me. I want to learn about the historical period of the game. Games can enhance understanding of history in a way books or films can’t. So historical accuracy needs to be a core piece of the design, while also being streamlined and playable. That’s a balancing act.

Grant: What sources did you consult regarding the history of these battles in 1862? What one must read source would you recommend?

Christopher: I include a bibliography in the game. For Antietam the classic is A Landscape Turned Red by Stephen Sears. For Mill Springs, Ken Hafendorfer’s book Mill Springs. For Valverde, John Taylor’s A Civil War Battle on the Rio Grande. For an overall excellent history of the entire war Battle Cry of Freedom by James M. McPherson. Finally, for folks in the U.S., walking the battlefields is essential. We are fortunate to have an amazing bounty of preserved sites to visit and one can learn more from a day on a battlefield than from a hundred written histories.

Grant: Why did you choose the battles included in the game? What would you say their general theme is?

Christopher: The battles were chosen to test the limits of the system I am using. I plan to use this system to explore many battles down the road, and wanted to ensure it was flexible enough to handle a variety of battle sizes, terrains, orders of battle, etc…

Grant: What is the scale and force structure of units used for this game?

Christopher: Players maneuver Brigades composed of Regiments and Skirmishers (abstracted, Battalion to Company sized units). Divisional Artillery (including off board direct-fire batteries), are also included.

Grant: How many maps are used in the game? What does the map look like and what area does it cover?

Christopher: The game has four maps, one for each of the battles. Three of the maps cover the entire battle area: Fox’s Gap at South Mountain, Mill Springs, and Valverde. Antietam was a huge battle, and our map deals only with the fight for Miller’s Cornfield on the morning of the 17th. Hexes are 100 yards across, and the maps are roughly 15 hexes by 20 hexes. That’s a relatively small footprint, so the system is designed to cover smaller battles or portions of large ones. Fortunately, there are hundreds of small battles that most other civil war designs are too zoomed-out to handle. Fertile ground for future games using this system.

Grant: What are the areas of major concern in regards to the terrain?

Christopher: The only thing I haven’t really dealt with in this volume are urban areas….fighting inside Gettysburg for example, or Fredericksburg. They’ll be interesting design problems when I get to them.

Grant: What is the anatomy of the counters? What special units are included?

Christopher: The counters are quite simple. The unit symbols indicate formation, which is very important at this scale, versus “uniform details”, which may be decorative, but are functionally unimportant. So, an infantry unit symbol indicates “formed” or “unformed”. Formed infantry is tough and hits hard. It’s not equipped to move through broken terrain or take advantage of road march. Artillery is deployed or limbered. Cavalry is either mounted or dismounted.

Special unit types would be Skirmishers, which have a variety of special functions, primarily screening friendly troops and harassing enemy formations. At Valverde and Mill Springs, I had to develop units representing irregular formations that weren’t part of the brigade structure. These are handled as “independent skirmishers”, which vary in a few key ways from the brigade skirmishers. Artillery units can have very long ranges at this scale, so some of it had be handled as off board units. These guns can target units on the board from as far as 30 hexes away, provided they can trace line of sight. Units on the map can return fire if they have sufficient range.

Grant: What does a game turn look like?

Christopher: Brothers at War uses a chit-pull system. At the beginning of the turn, two Activation Markers for each brigade (plus 2 for each side’s divisional artillery) are placed in an opaque container. Along with the activation markers is one Countdown Marker, which is used to determine when the turn ends. During the activation phase, these markers are drawn, one at a time, and placed on an Activation Track. The brigade indicated on the activation marker is activated: first the brigade Recovers (all “finished” markers are removed, and disrupted units attempt to rally). Then its Ready units may activate, one at a time or in stacks of 2, spending their movement points to do things like move or assault (spending movement points for each hex entered), fire (2 movement points), change formation (2 movement points), etc… When a unit has fired, assaulted, or spent its movement points, it’s marked finished, and another unit/stack is activated. When the brigade is finished, the next marker is pulled from the cup and that brigade activates. As activation markers are placed on the track, certain spaces will add additional Countdown Markers to the cup. Once 2 Countdown Markers have been pulled the turn ends.

Grant: How are Countdown Markers used? Why was this your chosen method to depict the passage of time? What interesting tension do these counters create for the players?

Christopher: Something I value as a designer and player is uncertainty. It tests a player’s courage and ingenuity. If everything is known, all the parameters of a question are understood, the task for you, as a player, is simply to figure out what the next optimal move is and then do it. If you do that better than your opponent, you will always win. War (reality in general) doesn’t work that way. You can make a brilliant decision, and then something goes horribly wrong. When you have a system with significant levels of uncertainty, your task as a player is to decide what gives you the best chance of success, understanding that it may not work out in the short run. If you make the best decisions overall, even if uncertainty turns against you, you have a good chance of winning. Even with inspired play however, there are no guarantees. That is the kind of game I like. Things can go very, very badly for you, despite you doing everything right. That’s a test of courage…can you keep making sound decisions and not get discouraged? If you can, your opponent will most likely face his own very, very bad moment in the future, giving you a chance to take advantage of it. That’s how life works, and makes for the most exciting narratives in games.

Grant: How is victory determined?

Christopher: Victory is battle dependent. Brothers at War has 13 different scenarios, each with its own victory conditions.

Grant: How are Battle Cards used in the game?

Christopher: Battle Cards affect nearly all the mechanics in the game in some way or other, so they ratchet up that level of uncertainty. What card is your opponent trying to set up to use? What is he likely to do that I can prevent or counteract with my own card? The cards create storytelling moments. One that’s always satisfying is “Stampede”. When a unit retreats (this is usually chosen by the retreating player, vs. a combat effect), you can play Stampede to cause an additional, adjacent unit to retreat as well. This can create a gaping hole in the enemy line at a key moment, creating opportunities for the active player.

Grant: How does combat work in the design?

Christopher: All dice rolls in Brothers at War use one (or more) d6’s, each roll succeeding on a 5+. Combat is resolved by throwing dice equal to the attacking unit’s firepower hoping to score as many successes as possible. If the attacker scores one or more successes, the defender then rolls saves (same idea, each save involves rolling a d6 looking for a success). Saves come from terrain, elevation, range, etc… The defender may gain 1 save by retreating. Each successful save roll cancels one of the attacker’s successes. All uncanceled successes inflict Hits on the defender. The first hit disrupts the defender. The second hit eliminates it. That’s where reserves come in. Each brigade has a limited number of reserves which it can spend to prevent its regiments from being eliminated. If a disrupted regiment takes two hits, its brigade can spend two reserves to prevent its elimination. Once all a brigade’s reserves have been spent, it can no longer prevent its regiments from being eliminated, and it becomes vulnerable to breaking (removing all its regiments from play).

Grant: What different types of Fire Attacks are there? How do they differ?

Christopher: Infantry and dismounted cavalry can fire out to 3 hexes in range (300 yards), with fire at 2-3 hexes generating saves for the defender. There’s been a lot of research in recent decades that shows that lethality beyond that range was negligible, even though a trained marksman with a rifled musket could fire much further than that with a high degree of accuracy. The “trained marksman” factor is the key… most troops weren’t. There were selected units in the civil war composed of hunters, marksmen, or trained sharpshooters. In the game, such units can deploy Skirmishers that can fire out to 4 hexes.

Artillery are rated for range: generally, 6 hexes for unrifled guns and 9-10 for rifled guns. These are “effective” ranges. All guns at 3 hexes gain 1 dice for using cannister, are -1 to hit out to double their printed range, and are limited to doing 1 hit maximum out to triple their printed range.

Grant: How does Assault work? Why is it necessary to include?

Christopher: Assault reflects fighting within 100 yards (one hex), it might be just fire at close range, or it might involve bayonets and sabers. There are no saves during an assault, so every success a unit rolls inflicts one hit. That makes assault decisive, and potentially damaging to both sides. The defender has an opportunity to avoid an assault by retreating but suffers one hit doing so. Long range fire in the Civil War was rarely decisive on its own. It served to “soften up” a unit so that the attacker could charge towards it and force it to break. The assault represents the culmination of that process. Formed infantry gains +1 to hit when assaulting (meaning it needs 4+ to hit). Disrupted units suffer -1 during assault (meaning they need a 6+ to hit). So, disrupting a target with fire, then sending in formed infantry is the key to a successful attack.

Grant: What are you most pleased with about the design?

Christopher: The battles tend to develop historically and are fun to play. Those were my key goals. You will learn how different Civil War battles happened, and why. The games always have great storytelling moments, when units hold against the odds, or entire formations break and flee. It feels very much like the history.

Grant: What other games are you currently working on?

Christopher: The sequel to my card game Napoleon’s Eagles is next up from Compass. The first game Storm in the East dealt with the battles of Leipzig and Borodino, two of the largest battles in the Napoleonic Wars. Volume 2: The Hundred Days deals with the Waterloo campaign, featuring all four key battles: Quatre Bras, Ligny, Wavre and Waterloo, as well as a scenario covering the entire campaign.

The game I’m finishing up right now is a fantasy wargame called Burning Banners, also for Compass Games. It’s a sprawling 9-year war set in an imaginary fantasy world, playable by up to six players (there are over 20 scenarios, each featuring different numbers of players, and vary in length from a few hours to a long weekend). The lore and history of the world are deep. Magic is handled through card play, while units fight on the map like a conventional wargame. Again, the aim is fun but immersive, combining fast play with lots of surprises and impactful decisions. When I was a youngster, Divine Right from TSR captured my imagination. This is my ode to that game. I’m proud of how it’s developed. It’s going to be gorgeous visually…I’ve done hundreds of original pieces of artwork for it, including a huge hand drawn 44″ x 34″ map. I will be delivering the final files to Compass this fall (2022).

After that, it’s on to Volume 2 of Brothers at War! This time we’ll travel to the outbreak of the war: 1861. Right now, the battles that will be covered include Bull Run in Virginia, Belmont (U.S. Grant’s debut as a commander) and Wilson’s Creek in Missouri. The fourth battle is up for grabs… possibly Ball’s Bluff or one of McClellan’s West Virginia battles. We’ll see! Thanks for giving me the opportunity to chat with you.

Thanks so much for your time in answering our questions Christopher and it was a pleasure to meet you at WBC this year! Really am excited about this game and about your upcoming Burning Banners.

We videoed a quick designer interview covering Brothers at War: 1862 at WBC and you can watch that at the following link:

If you are interested in Brothers at War: 1862 you can order a copy for $79.00 from the Compass Games website at the following link: https://www.compassgames.com/product/brothers-at-war-1862/?sfw=pass1665069911

-Grant

Burning Banners – related to Burning Wheel TTRPG?

LikeLiked by 1 person

No. Total new creation by Chris.

LikeLike