A few months ago, I came across a very interesting looking game that focused on the Maccabean Revolt against the Seleucid Greeks in Judea in 167BC. This game was from a new company called Catastrophe Games and was heading toward a Kickstarter in late February 2021. To my knowledge, there has never been a game on this subject and that immediately piqued my interest but also the fact that the design is asymmetric in the way each of the factions in the game work. I reached out to the designer Robin David and he was eager to share information on the design ahead of the Kickstarter.

If you are interested in the game and want to check out the Kickstarter Page you can do so at the following link: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/judeanhammer/judean-hammer

Grant: First off Robin please tell us a little about yourself. What are your hobbies? What’s your day job?

Robin: Hello. I’m an English teacher and a videogame and television writer, living in a small town just outside of Dublin, Ireland. I’ve been designing tabletop games – in all kinds of genres – as a hobby for about six years now. That’s culminated in a few published designs, some self-published Kickstarter projects, plenty of print and play games, and so on.

Grant: What motivated you to break into game design? What have you enjoyed most about the experience thus far?

Robin: I consider myself “a maker”, by which I mean, whatever hobby I find myself in, I strive to make things related to it. Well, when I discovered tabletop gaming and wargaming in my late 20’s, I knew I wanted to start making games! By far, the most enjoyable aspect has been the excitement of getting a game published – going to the conventions to play it with the public and seeing people enjoy it first hand. Hopefully, we can see more situations like that in the near future.

Grant: What designers have influenced your style?

Robin: Right now, I split my design time fairly evenly between Eurogames and wargames, and each of those comes with significantly different influences, but overall I really value designers who are able to boil games down to a simple core and shift the complexity over to player decisions rather than rules minutia – that’s exactly what I strive to do too. In wargaming, I find that I’m really inspired by Richard Borg and Mark Herman. I’m adoring Commands & Colors: Medieval at the moment. My favourite wargames are definitely CDG’s, which often shift rules out of rulebooks and onto cards. They let you jump in without knowing EVERYTHING!

Grant: What do you find most challenging about the design process? What do you feel you do really well?

Robin: Right now, the biggest challenge is definitely in getting playtests done. In normal times, I run a public playtest group every two weeks in Dublin – called Playtest Dublin. Designing games without that sounding board is a different experience and is leading to quite different designs on my part.

What I do well in game design is really up to the player to decide, but I always endeavour to make my games as streamlined as I can, without sacrificing too much gameplay for that purpose. I want players to be able to jump in and be able to enjoy the fullness of a game without having to go and check rule 3.2.4 again…

Grant: What is your upcoming game Judean Hammer about?

Robin: The game is about the Maccabean Revolt, which was a fascinating uprising that happened in 167 BCE. The Seleucids were in control of Judea at the time and were forcing the locals to convert to Hellenism. Well, some locals refused – the Maccabeans – and they started a bloody guerilla campaign that spread across the region. The Seleucids didn’t see the revolt coming, nor did they anticipate the tactics the Maccabeans would use, and despite their military strength, they lost control of Jerusalem. This is the story that forms the basis to Hannukah.

So Judean Hammer puts two players in the shoes of the Maccabeans and the Seleucid Greeks and lets them battle it out over ancient Judea. It’s a card-driven game with a small footprint and a low rules overhead.

Grant: What does the title mean in relation to the history and your game?

Robin: Maccabee was the nickname given to Judas – the leader of the revolt – and the name quite literally means “sledgehammer”. It might have been a reference to his weapon of choice or it might have been a reference to his fighting style. Regardless, he and his forces were known for quick strikes and ambushes – exactly what you’ll do in the game.

Grant: What inspired you to design a game on the Maccabean Revolt?

Robin: I’ve always really enjoyed asymmetric wargames and guerilla warfare. Well, the Maccabean Revolt is one of the iconic guerilla wars of history and I’ve wanted to make a game about it for some time. Even though the Maccabeans were at a huge disadvantage, they were able to leverage what they did have into a victory. It’s inspiring!

Once I’d chosen the conflict, it was a matter of finding the right mechanisms to suit – something that could present the asymmetry and let the players perform tricky manoeuvrers around one another.

Grant: What from the history did you need to make sure to include in the design?

Robin: There were a few key aspects of the revolt that I wanted to make sure were in the game:

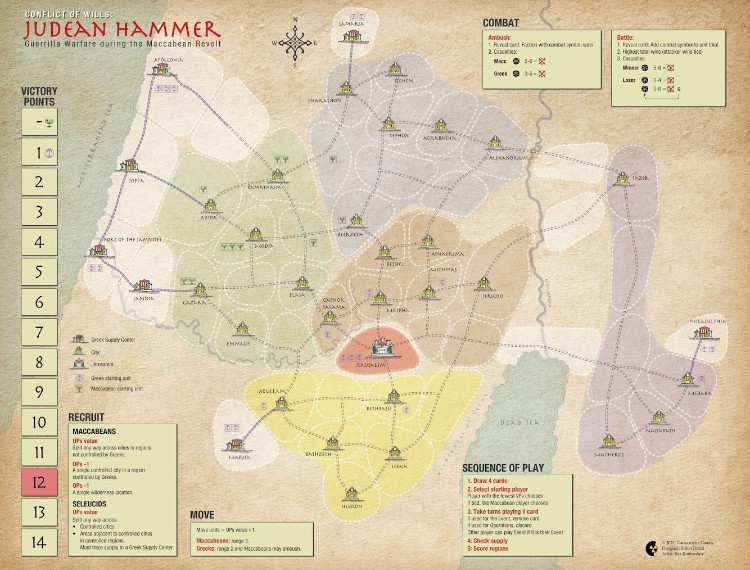

The Seleucids didn’t expect a revolt and the military leaders in Judea were inexperienced and undertrained. So in Judean Hammer, the Greek player relies heavily on keeping contact with Greek cities in other regions, hoping for timely reinforcements. In game terms, if the Maccabean player can block off Greek supply, the Greek player suffers heavy penalties. This makes the game really tense.

The Judeans were masters of guerilla warfare. They regularly sprang out of the wilderness and performed deadly ambushes, hindering Seleucid attempts to pacify the region. In Judean Hammer, the Maccabean player is able to recruit far more easily than the Greek player (who can only recruit where they have a level of influence), appearing in the most awkward of places and often striking supply lines that very turn.

While the revolt began in Modin, the key objective was Jerusalem. Once it was taken, Greek strength in the region was shattered and the Maccabeans could appeal to the Romans for peace. In Judean Hammer, Jerusalem is clearly the most powerful location, granting a significant boon – points and card events – to whoever holds it.

Grant: How did you make each side play differently while simultaneously keeping the game somewhat balanced?

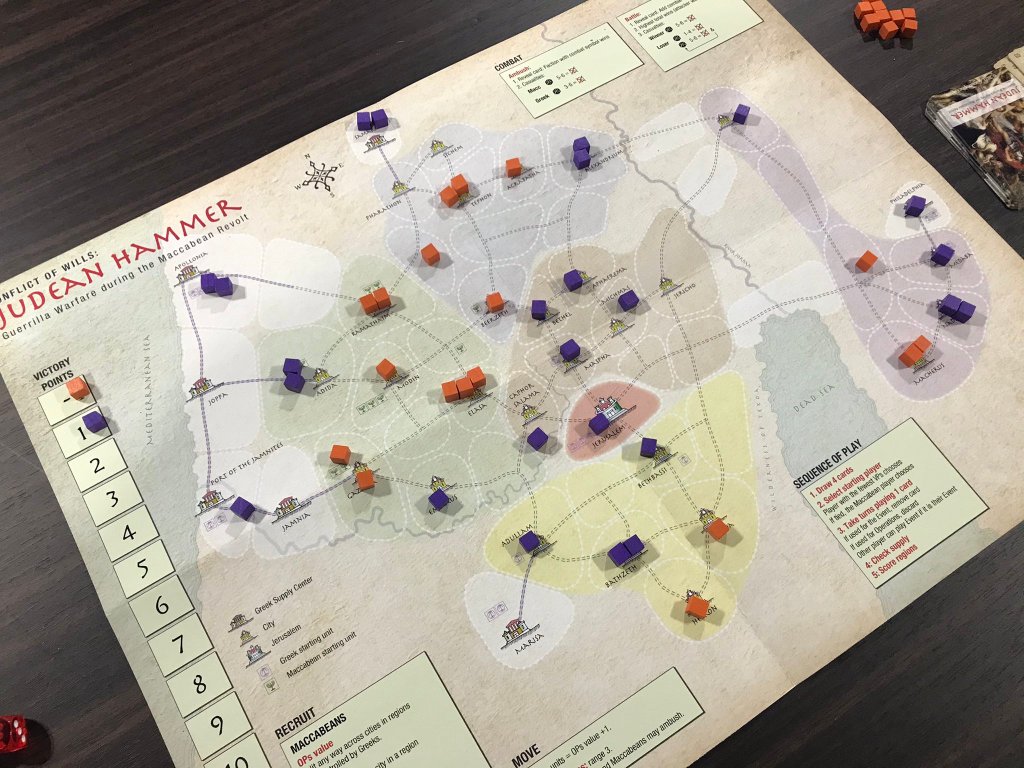

Robin: With a lot of experimenting! The most significant asymmetries come in recruitment rules, which I touched on before, the need for supply (the Greeks need it, the Maccabeans don’t) and the ability to use guerilla tactics. Overall, this means that the Maccabeans need to play a very aggressive role, while the Greeks are generally more defensive and will project strength from regions they already control.

The way combat is resolved in the game also helps balance things out. You see, when a battle is begun, the players flip a card off the shared action-card deck and applies the combat modifier on that card – granting bonus strength to either the Maccabeans or the Greeks. Simple enough, and the deck starts out evenly balanced between the two players. Now, during a turn, when a player uses a card, they can either use it for a weak effect (recruit or move) and it will get shuffled back into the deck, or they can use it for a strong event (all kinds of effects), but that will remove the card, and their combat modifier, from the deck. So, if a player uses all their events, they will get loads of units out, secure key locations, etc., but they are going to have a tough time when it comes to battles. While a player who only uses their events at key moments will have much better odds when it comes to a fight.

Just one more point about balance – the game is short. Typically about 4 rounds and usually finished in about an hour. It’s much easier to balance a short game – when one player gets ahead, they can only leverage that for a short time.

Grant: What are the major differences between the Maccabeans and the Greeks?

Robin: As I mentioned before, they have their own rules for recruitment and movement, the need for supply, and the events on the cards. One thing that I didn’t mention is that the Maccabeans have an ability to ambush Greek movement. Once per turn, when the Greek player is moving units adjacent to Maccabean units, the Maccabeans can TRY to spring an ambush. As above, they rely on drawing an appropriate modifier from the deck to succeed, so maybe the Maccabean player should avoid playing all their events too soon. But this key ability can halt Greek movement and really throw a spanner in the works.

Grant: The game is card driven. Why did you feel this was the best mechanic to tell the story?

Robin: I’m a huge fan of card driven games. I like that they provide a fog-of-war, allow for exciting moments, and help simplify the core game rules. I think the fog-of-war is really important for a game about guerilla warfare. If the Greeks know too easily what the Maccabeans can do that turn, how would they be surprised? And if the Maccabean player knows too well the available Greek tools, then it would too easy for them too!

Grant: How are the Operations Points used by the players? How do you go about assigning the different values?

Robin: Operations Points provide the actions a player can take when they can’t or don’t want to do a card event. They allow a player to only move or recruit following standard rules. If a player is holding an opponent’s event, they only have the option to use Operations Points. Values are typically in line with the strength of the event on the card so it really became about making the event effect match the Operations Points on the card.

Grant: How are the cards used for the Events? What happens when an Event is played?

Robin: Players can play a card associated with their faction and choose between the event or the operations points. Most of the events are unique and provide stronger abilities – they can move AND recruit, or battle with greater ferocity, those kinds of things. As mentioned though, if you take one of these events, you must also remove the card and your own modifier from the game.

Grant: Why did you make the decision to have opponent Events go off when a player takes the Operation Points from an opponent aligned card?

Robin: So when you play a card with an opponent’s event, you have to use it for the Operations Points. Then, after you have taken your action, the opponent can choose to trigger the event. This is exactly the same as if they had played it – they will remove the card from the game, along with the attached battle modifier. Now, this helps balance the game – if you have a terrible hand of cards at the start of the round, there is a good chance that your opponent is holding a bunch of your cards. So you’ll end up getting these bonus turns.

It also creates a lot of tension. When you hold an opponent’s event card, you know you are going to face this tough event at some time in the round. All you can do is control WHEN it happens and maybe try to make it a bit less enticing and useful!

Grant: Why are there some Maccabean Events and some Greek Events that if played actually hurt them with the Event?

Robin: So there a few card events in the deck that buck the trend of being souped up abilities. For both factions, there are actually cards which they can choose to trigger and that will hurt their own forces. One particularly brutal event requires the Maccabean player to remove all Maccabean units that are next to the Greek Supply Centers. BUT these events, while causing a short-term setback, allow the player to remove a combat modifier belonging to their opponent. Now the balance of the deck is more in their favour for the long term – if only they can hang on for long enough to take advantage of that.

Grant: How does combat work in the design?

Robin: Combat is super fast and easy. A battle breaks out at the end of a turn whenever the two sides occupy the same location. We compare numbers of units and flip a card from the shared deck, which modifies these numbers. A card event might modify the numbers too. Now, whoever has the higher value (and attackers win ties) wins the combat and both players roll dice to determine unit losses. If the attacker can eliminate the defender, the attacker takes the location.

Grant: Where did the idea for combat modifiers on cards come from? What type of strategy does this create?

Robin: The idea behind the shared deck modifying battle is that it creates a lot more moments for decision making. Playing a card for an event is no longer always a good thing. There are only 26 cards in the deck and taking out even just a couple of your own events can swing the deck in favour of your opponent. I find that tension really satisfying. Players shouldn’t always be exerting their forces to their maximum – sometimes you should hold back and those big moves should be well considered.

Grant: How are losses from battles decided?

Robin: Initially losses were determined through a fairly standard CRT. It worked fine. But when I brought the game to Catastrophe Games, Tim Densham really wanted to figure something else out – something a bit more accessible and a bit more fun. Tim devised a simple mechanism where both players roll dice for their own losses – the winner has slightly better odds to come away without losses. The loser will lose at least one unit and perhaps more – if they roll a 5 or 6, they lose a unit and roll again. This ended up being remarkably close to the original CRT but much more fun to do.

Grant: Why the exploding 5-6 result? What does this reflect from the history?

Robin: Simply put, losing a battle needs to be scary! It shouldn’t be a given that you just leap into a battle. And even if an opponent has a larger force, as was often the case, a well planned assault has the potential to devastate.

Grant: How does Ambush differ? How should the Maccabean player use best this key ability?

Robin: Ambushing is a Maccabean ability that is primarily used to halt Greek movement, although it does whittle down forces just a little bit. The Maccabeans are the manoeuvrable force in the game, and the ambush ability let’s them show off these skills, granting free movement opportunities, etc.

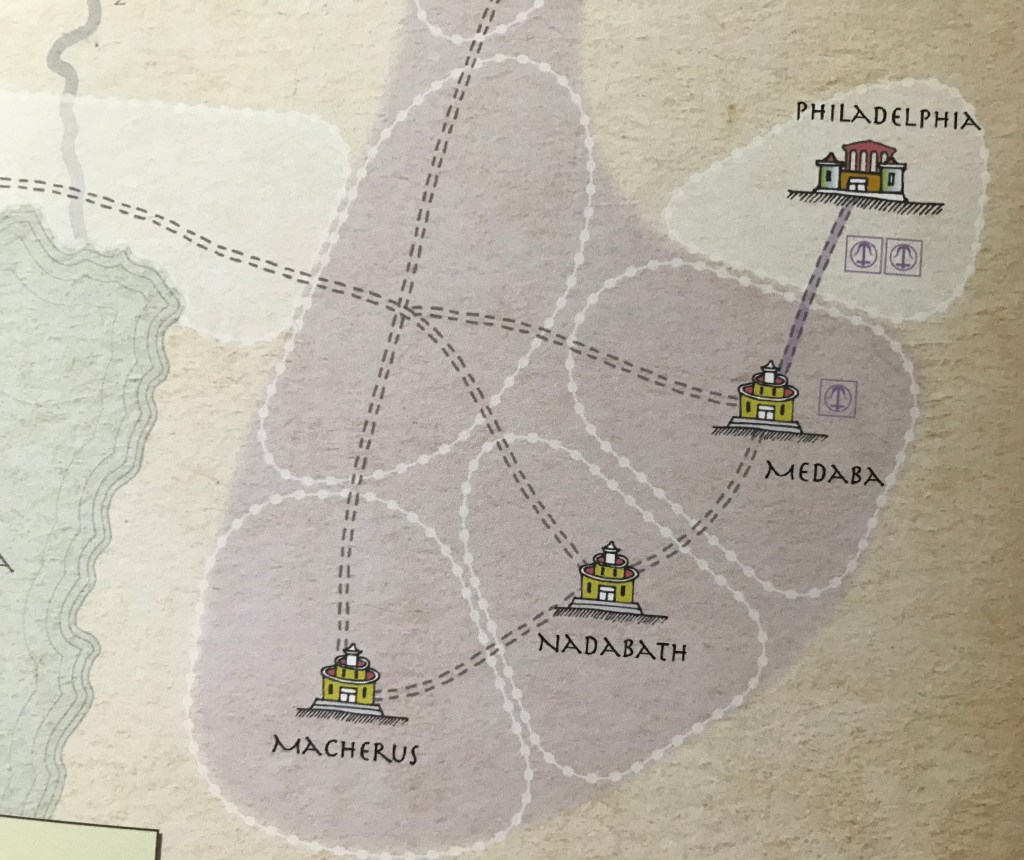

Grant: How does Supply effect the game?

Robin: Only the Greek player needs to supply their units and this supply is checked when recruiting and at the end of a round. Supply is available if the Greek player can trace a route back from a given unit to a Greek Supply Centre without encountering Maccabean units. Now, if Greek units at a given location cannot trace supply, they can’t call in reinforcements until they get that supply line open. And even worse, at the end of the round, every Greek controlled location that is out of supply will lose one unit, potentially costing control of a whole region. Supply checks happen just before scoring regions, so that’s a big deal!

Grant: How did you decide on the locations of Greek Supply centers? There are really a lot of them. Why so many?

Robin: The Supply Centres were based on real locations of Greek cities at the time. There are a lot because this is the form of Greek strength in the game. The Maccabeans have a lot of tools at their disposal – just a single Maccabean unit springing up in the wilderness can be enough to disrupt Greek supply – so there needs to be options for the Greek player.

Grant: What strategies should players take in relation to Supply?

Robin: If the Maccabean player manages to cut off supply to a significant area, that is HUGE. The Greek player could atrophy 6 or 7 units in that round and it could easily swing control of a region. If it happens with Jerusalem, well, it’s more or less game over for the Greeks! The Maccabean player should be seeking every opportunity to grab this initiative, using ambushes to get free movement, and using their ability to recruit into the wilderness. The Greeks should be reinforcing their supply lines, distracting the Maccabean player with other, more pressing battles, and keeping several supply routes open, if possible. The Greeks are stronger – they have more units on the board and better locations, if they can keep hold of it!

Grant: How are Victory Points scored?

Robin: At the end of every round, we check who controls each of the five regions. This is down to who occupies the most cities in a given region. Then players score 1 point for each region they control. Jerusalem is also worth 1 point to whoever controls it.

Grant: Why does the Greek player start the game with a VP lead? Why when the Greeks appear to be setup from the start to score 3-4 VP’s in the first turn if they hold their locations?

Robin: In many ways, this is a game of momentum and with the potential for supply issues, the Greeks have a much greater chance of losing that momentum. Sure, they can reinforce their current locations and do OK, but they won’t win that way – the Maccabean forces will spring out of the hills, surround them, and clean up.

That opening board state looks very unfair on the Maccabean player – particularly with the Greeks having a big force in a well supplied Jerusalem. But the Greek player is going to have similar feelings about the Maccabean player when they get ambushed!

Overall, playtests have shown that both sides win a roughly equal number of times.

Grant: How does the game come to an end?

Robin: The game ends when a player gets a total of 12 points for control of regions/Jerusalem. That generally takes around 4 or 5 rounds. The game can also end early if players are greedily playing all the events in the deck and there are not enough cards left in the game at the start of a round. That can happen as early as round 3 and in that case the player with the most points would win. And if there’s ever a tie for points, the Maccabean player wins.

Grant: What are you most pleased about with the outcome of the design?

Robin: I’m really happy that each play of the game can feel very different from one another. Even for a static set-up, things can pan out very differently, with different regions becoming key and different approaches working out or failing for players. And that’s all on the back of a very easy-to-understand game system.

Grant: What type of experience does the game create for players?

Robin: I usually find that games are really close – often just a point or two between players – and it allows for lots of heroic moments. It’s an amazing moment if the Maccabean player gains control of Jerusalem – it starts the game so heavily defended!

I think the game is really tense and exciting and, even though it’s short, it rewards strategic planning and considered moves.

Grant: What other designs are you currently working on?

Robin: I always have a load of games on the go. I will be making more games using the same system as Judean Hammer. The next one, I think, is called No Tyrants, No Slaves and is about the Philippine-American War (1899-1902) – again, Guerilla fighters against a huge overseas force. It’s quite a different experience because this time, it is the overseas force that controls supply and is able to cut off the guerilla fighters.

I’m also working on a game about the Bruce invasion of Ireland (1513 AD). It’s a 4-player only game, which forces players into strange and uneasy alliances. Players take roles as the Scottish, the Gaelic Irish, the Anglo-Irish, and the English. The English and the Scots are massive forces, constantly fighting, while the two Irish factions sometimes help each other, sometimes help their foreign-ally, and sometimes try to undermine that same power. It’s been a fun project and has had some significant changes in recent months, but it’s so hard to test during the pandemic…

Thanks for the excellent information about the game and its design process. As you mentioned, I too love the CDG mechanic and feel that it is the perfect form to tell the details about history and make sure they are included into the game, not deterministically but with the opportunity for those events to happen and effect the course of history. I have played this game several times now and agree with most of what Robin said about the number of decisions, the tension about battle and losses, the interesting asymmetry of the two sides and the simplicity of the rules (in fact most of the rules are written on the board itself for easy reference such as Recruiting limitations and movement).

If you are interested in the game and want to check out the Kickstarter Page you can do so at the following link: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/judeanhammer/judean-hammer

-Grant

Very interesting. I signed me up!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Got me …

LikeLiked by 1 person