Brian Train is one of my favorite designers. I simply love his style of games with their focus on insurgency and urban warfare and have loved many of his games including Winter Thunder, A Distant Plain, Colonial Twilight and The Scheldt Campaign. He has also done many interviews for our blog and I truly appreciate his willingness to do them. He always takes them very seriously and provides great and detailed looks into the games. To date, we have done 7 interviews with Brian, and this one makes #8 so you can see that he has a lot of great games, and a lot to say!

Recently, I asked him what he was working on and frankly the flood gates opened as he shared updates on about 4 different projects. One that looked very interesting to me was his upcoming quad The District Commander Series and its first volume called Maracas.

*The images used in this interview were cajoled out of the designer against his free will and choice as I simply needed some pretty pictures to break up the monotonous text. I have been told that these are near final graphics but still are subject to change.

Grant: What’s been going on since we last spoke in 2018? Sorry we haven’t stayed in close contact.

Brian: Yes, you are right, it’s been about a year since we last talked. Certainly we have both been busy!

Last time we talked, you mentioned wanting to attend CSWExpo 2019 in Tempe, AZ, and meeting your second favourite Canadian – me, that is, after Geddy Lee. Well, I didn’t see you at the Expo this year…I generally go to only two conventions a year, this one and BottosCon, a small weekend Con run by my friend Rob Bottos in Vancouver in November. I had a good time as always, perhaps you can make it next year. And I note that Geddy (as I call him) has just wrapped up a long book tour for his Big Beautiful Book of Bass; maybe he orbited somewhere near you.

Editor’s Note: I don’t know about you guys but I definitely see the resemblance in these two cool dudes hailing from the The Great White North!Grant: I understand you are designing a new series quad called The District Commander Series. What is the focus of this series and what new directions in counterinsurgency will it explore?

Brian: The District Commander series is an idea that I started working on in 2012. It in turn had evolved out of an unpublished but rather ornate game I did in 2010 called Kandahar I (not at all like the Kandahar that was eventually published by One Small Step in 2015, that one started life as “Kandahar II”) that was in turn inspired by another unpublished game from 2008, called Virtualia, that was an amplification of many of the mechanics in my Tupamaro game (which we have discussed before), and even some bits and pieces from Green Beret. So my ideas might evolve, but my lack of talent for clever titles stays pretty much constant.

I had the vague idea that this could be a simple manual game I could give to the professional military, who could use it in classes to cover the “Clear and Hold” concept contained in US Army counterinsurgency doctrine (later it became “Clear, Hold and Build”) with no need for any technical gizmos more advanced than a glue stick. But it was a silly notion. Professional military people are usually far too busy and time-starved to indulge in anything like this – even if many of them do realize the value of manual games over computer ones…even if you get rid of the dice that make it seem a trivial exercise to some senior officers…even if you split it into basic, intermediate and advanced versions, etc.

Chapter 3 of the US Army Field Manual 3-07.22 Counterinsurgency Operations defines and describes this in the following:

“The clear and hold operation focuses the three primary counterinsurgency programs (Civil-Military Operations (CMO), combat operations, and Information Operations (IO)), supported by intelligence and psychological operations on a specific geographical or administrative area or portions thereof…. The clear and hold operation is executed in a specific high priority area experiencing overt insurgency and has the following objectives:

· Creation of a secure physical and psychological environment.

· Establishing firm government control of the population and the area.

· Gaining willing support of the population and their participation in the governmental programs for countering insurgency.”

Anyway, the first District Commander module was a simple “Red vs. Blue” test bed for all kinds of mechanics and variations I wanted to try at the time, that reinforced these objectives.

Grant: Why is this an important project for you?

Brian: As you know from past interviews, at least half of my body of work is about some aspect of irregular warfare. I am always looking for different ways to explore the asymmetries between the antagonistic parties, and the oddities of time and space that irregular warfare (or a game on irregular warfare) exploits. Certainly no revolution, insurgency, guerrilla war or dinner party is exactly like any other, but I reasoned that there were certain basic operations that were common to any and every armed force arrayed in the conflict; you have to move your people and things around, you have to do something about the civilian population, you need to get or organize more goodies, and so forth. I’d already done something like this in my “4 Box” series of games that evolved over a number of years, in response to both the different situations and better ideas I’d had over time…so Shining Path begat Algeria which begat Andartes which begat EOKA which begat Kandahar, but I didn’t go back and retrofit later versions of the rules to the earlier games. So why not take a page from the old SPI quadrigame book and create a set of core rules for people to learn out of the gate, with modules reflecting the peculiar nature of each of the conflicts through slight additions, exceptions and changes to those core rules?

Grant: What periods and locations will the games focus on?

Brian: Right now there are four District Commander modules I have done:

• Mascara, which takes place in the Zone Nord Oranais, the hill country southeast of the city of Mostaganem, Algeria, about 1958-59.

• Binh Dinh, in that province in the Central Coast of Vietnam, 1969.

• Kandahar, in that province of Afghanistan, about 2009-10.

• Maracas, in that fictional large-city capital of the nation of Virtualia, 2010-20.

Certainly I might work on others in the future…Iraq, Mexico, the Philippines, who knows.

Grant: I understand this is a dice-less system. How does that work in the design and what advantage does it give gameplay?

Brian: During the Operations Phase each player will normally hold a hand of Chance Chits so as to influence operations. These chits will be expended during play as players perform (or defend against) certain Missions. Note that while chits initially are drawn randomly, the chits you play during the turn are selected deliberately.

It’s like being able to choose many of your die rolls in advance; the randomness comes from the initial random selection at the beginning of the turn, and the decisions made by each player because of the unequal ratings of the chits…you might want to play a chit that is not good for one particular situation, in order to save a better one for a different situation later. Also, you don’t always have to play a chit, and each player will always have one blank chit (with ratings of zero) that will always sit in their hand of chits and can be used to fake out the other player.

Grant: Please tell us more about these Chance Chits. And what are the Intelligence Chits and how are they used?

Brian: Chance Chits are used by the players to accomplish things during the turns composing the game. They are an abstraction of the amount of support the authorities to which the players are responsible are prepared to provide, and the capacity of the troops involved to complete their assigned tasks. They represent both material goods (e.g. money, weapons, ammunition and explosives, vehicles, choice recruits) and intangibles (patience, time and effort spent preparing for operations, staff officers’ experience and competence, priority for administrative and intelligence resources, etc.). There is no physical equivalency implied between one chit held by the Government player and one held by the Insurgent; they have different scales of effort.

Each player will get an allotment of chits at the beginning of each turn to help them to accomplish various tasks. The units the player controls also have a limited organic capability to do things, so it is not always necessary (or desirable, or even possible) to play a chit as well.

Each Chance Chit has three ratings on it, from 1 to 5: Intelligence Rating (eye); Troop Rating (medal); and CIMIC Rating (heart). The Combat Units the players have also have such ratings.

Chance Chit random draws are also made to show the uncertain reactions of civilian populations when trying to recruit, or the attitude of the Higher Authority, or to derive random events.

Intelligence Chits are used for several functions in the game. They are drawn randomly out of a pool. The Government player generally uses them to locate and engage Insurgent units on better terms, and the Insurgent player uses them to evade Government scrutiny, have more effective Ambushes or Attacks or spread further confusion. There are also blanks that show faulty intelligence. Exclusive game rules and modules add other types of Intelligence Chits and functions: for example, in the Maracas module, the Government can get Informers who nullify the Area’s Terrain Modifier in Patrol Missions. They are swiftly and cruelly removed if the Insurgent player successfully disrupts all paramilitary units in the Area in an Intimidate mission (showing the loss of police protection – guard your snitches, lest they get stitches!). The Government player can also draw a Command Node Identifier, which forces the Insurgent to give away where the matching Command Node counter is.

Grant: What is the “No Chit, Cherlock” optional rule? Love that Brian Train humor.

Brian: Well, someone has to love it. If you are playing the game alone, there is not a lot of suspense in hiding a rack full of Chance Chits from yourself, so you might want to just roll a six-sided die in any situation where you would play a chit. Because the three ratings on the chits are not equally distributed, and the outcomes on a die are equally probable, this will add a greater degree of randomness to the game than was intended as you can no longer choose chits to fit the mission. There will also be a greater range of results as the chits are rated 1 to 5, while the die gives results of 1 to 6.

Grant: How are Activations handled? Why does the system allow players to “run a deficit” on Task Points? What does this model in the real world of insurgencies?

Brian: During a turn, players activate stacks of units to perform missions with Task Points, representing fairly abstractly the overall staff competency, cohesion, logistics and so forth of that side. Each side has a Task Point Maximum that is reset at the beginning of each turn, and during play you expend points (usually 1 point per Mission, though the same stack can perform multiple tactical class missions). You can expend more than your initial allotment, at the price of driving your Maximum down in future turns; you can regain and build up your Maximum by leaving Task Points unexpended at the end of the turn. You can optionally change the ratios by which you lose and regain points, to show the overall effectiveness (or brittleness) of a side.

This mechanic is not there just as a reflection of irregular warfare, but as a rebuke to many wargames I’ve played in the past, at least among the simpler designs: all sides can go all out, every turn, with no ill effects. Move everything at full speed down the road every day, everyone gets to fight a full scale battle every turn…Nonsense! Staff officers get tired, vehicles wear out, ammo runs low, morale and discipline can take a nose dive as people get exhausted. You can take a run and go into overdrive for a bit, but at a price, but then you need to pull back and do a bit less in order to regain your potential for a good tempo of operations.

This mechanic is not there just as a reflection of irregular warfare, but as a rebuke to many wargames I’ve played in the past, at least among the simpler designs: all sides can go all out, every turn, with no ill effects. Move everything at full speed down the road every day, everyone gets to fight a full scale battle every turn…Nonsense!

Grant: What is the basic Sequence of Play?

Brian: Each turn begins with a Planning and Preparation Phase, during which players will resolve a random event, receive their turn’s allotment of Task Points (TP), and prepare for action in the subsequent Operations Phase (they can expend TP to undisrupt units, and to remove hits from regular force units). Both sides will then deploy counters representing troops onto the map. Optionally, there is an Intelligence Segment where players will acquire Intelligence Chits for use later.

After this, there is the Operations Phase, during which both players will expend TP to perform discrete operations (missions) with stacks of units. The action will shift back and forth between the players during the Phase as they resolve actions in the different areas on the map. Some missions are tactical missions; that is, straightforward military tasks such as performing patrols, ambushing or attacking the enemy forces, or moving from place to place. These missions may be performed multiple times by a stack during the Phase since they are shorter in duration. Other missions emphasize the “non-tactical” end of the campaign, mainly establishing friendly or reducing enemy influence or control of a given area, or recruiting or training troops. These missions take more time to perform and so may be the only mission performed by a stack in the Phase.

Finally, there is a Turn End Phase, where both players may redeploy their units to the Unit Box, adjust their TP Allotments, and record Victory Points as directed by their current Strategy. They may also appeal to their respective Higher Authorities for additional resources.

Grant: Why does the sequence start with a Planning and Preparation Phase and how does this reflect real world methods?

Brian: Well, before you go out to play, you have to get ready and suit up. You have an opportunity at this point to see to the overall health and combobulation of your forces, organize them into task-oriented stacks, do some Intelligence Preparation of the Battlefield, and so forth.

Grant: What random events are included and how are they introduced into play?

Brian: There is a random event determined each turn by drawing two Chance Chits from the pool and reading their Intelligence Ratings. This gives a random event result that the players try to resolve if possible. Each module has a different Random Events Table (I love these things and try to put them in every game I design). So in Maracas you can have things like:

• Black Market. The Insurgent gets 1 free Infrastructure Unit anywhere on the map, or they may place up to 2 Criminal units (if available) in the Area or Areas of his choice. The Government player adds 2 TP.

• Struggle Session. The perennial discussion on tactics continues, and one side temporarily has the upper hand. This turn only, the Insurgent player must conduct either Tactical or non-Tactical missions; they may not do both.

• Coup Scare. The Government player must immediately place 3 combat units, from the Available section or from those already on the map, in the Quick Reaction Force (QRF) section of his Unit Box. The units may not Move out of the QRF section during this turn.

Grant: What occurs during the Operations Phase and what options are available?

Brian: The Insurgent player will begin by choosing one Area on the map to have the Combat Units there perform operations, in the form of discrete missions. The player who currently has the higher number of Task Points has “Tactical Initiative” (Insurgent player wins ties) and may EITHER perform missions with one stack of his units in the Area, expending TP as he goes until he wishes to stop, OR he may pass. If he passes, or when he stops performing missions with that stack, the player who now has Tactical Initiative (which may be the same player) may now perform missions with one stack of his units in the Area, expending TP as he goes until he wishes to stop, or he may Pass. The Tactical Initiative will swing back and forth between players depending on what they are doing.

When both players pass in succession the Insurgent player chooses the next Area to perform operations. He may not return to an already-activated Area, and he must activate all Areas on the map that have units in them (the order in which he activates the Areas is up to him, though). When all Areas have been activated and all activity completed, the Operations Phase is over. As players go across the map, they mark activated Areas with a bingo chip, tile spacer or other strangely-well-suited household object.

Players can choose from the following missions:

• Patrol, Attack, Ambush and Move Missions are called “Tactical Missions”. They may be performed by a given stack of units any number of times during the Operations Phase, at the rate of 1 TP expended per mission.

• Building or Reducing Infrastructure, Recruiting/ Promoting Militia, Intimidate, and Removing Terror Missions are “non-Tactical Missions”. These represent activity sustained over a long period of time, weeks if not months. So if a player chooses to have a stack perform one of these missions, it costs 1 TP (because these kinds of things need time more than they need a lot of resources) and will be the one and only Mission performed by that stack during the Phase.

Insurgent units can hide out in the Underground box of an Area, where they are generally safe from interference, but may perform only non-kinetic things: Build Infrastructure, Recruit/Promote Militia, or Remove Terror missions.

Grant: Secrecy and hidden information seems to be a large part of the design. Why was it important to include this and how does it affect play?

Brian: Hidden information is another thing that doesn’t get done very well in most wargames. I can understand why; a lot of people just want to play, and sure we should let people enjoy things. But let people sit down to play a double-blind game or some other game with a lot of unknowns, and watch how their style changes!

Hidden information is another thing that doesn’t get done very well in most wargames. I can understand why; a lot of people just want to play, and sure we should let people enjoy things. But let people sit down to play a double-blind game or some other game with a lot of unknowns, and watch how their style changes!

It’s also important to know as much as possible about the enemy, and to make that as difficult as possible too. Separate record tracks and holding boxes are provided for each player to keep track of his various Points and units during the game. The number of Chance Chits and Victory Points a player holds, as well the contents of his Unit Box, are a secret: the player is under no obligation to tell the other player anything about them except when it materially affects the operation of the game (for example, when announcing he has sufficient VP to end the game). The number of Insurgent Task Points is a secret, but the number of Government Task Points is not; the Insurgent must know this in order for players to determine which side has Tactical Initiative in a given Area in the Operations Phase – but he can lie about the number of TP he has, to make the Government player think he has fewer than he actually does.

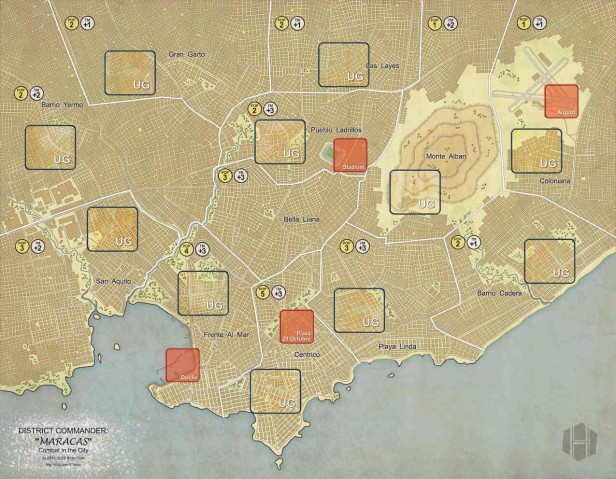

The Insurgent player’s units are concealed (placed face down) unless they have been revealed (turned face up) by a Government Patrol mission, have performed a mission of their own, or otherwise exercised their abilities. He also enjoys the use of an Underground (UG) box in each Area of the map. This represents space or time where he can hide out covertly, though with limited actions open to him. Normally the Government player cannot interfere with units in the UG box, but can perform Patrol missions (representing surveillance and population control measures) to move them out of the box to be “at large” in the Area. In the Turn End Phase, all Insurgent units are moved back to the UG Box of the same Area; non-Militia units may also go to the Available section of the Unit Box for redeployment elsewhere on the map in the next turn.

As an optional rule, players may use Intelligence Chits to peek at the other player’s unit boxes, or current strategy, or ask them one (game-related) question they must answer truthfully.

Grant: What troops are available to players to deploy on operations? What is the unit scale?

Brian: Unit scale is really variable; small group or so for the Insurgents, groups of technicians/operators up to companies and battalions for the Government.

Grant: What are the different combat units and what is the anatomy of the counters?

Brian: Combat units have three large numbers beside the unit icon. From top to bottom, they are the Intelligence Rating (IR), the Troop Rating (TR), and the CIMIC (Civil-Military Cooperation) Rating (CMR) of the unit. Respectively these represent:

Brian: Combat units have three large numbers beside the unit icon. From top to bottom, they are the Intelligence Rating (IR), the Troop Rating (TR), and the CIMIC (Civil-Military Cooperation) Rating (CMR) of the unit. Respectively these represent:

• IR = how good the unit is at finding, evading or outwitting the enemy (searching an area, patrolling, operational security, setting ambushes and traps etc.);

• TR = how good the unit is at fighting the enemy (partly a measure of the unit’s intrinsic firepower, but more a measure of its morale, discipline and cohesion in battle);

• CMR = how competent the unit is at establishing civil-military cooperation (activities that not only promote the physical security of the local inhabitants, but also confirm or deny local support of the government or the insurgent movement – depending on which side you’re playing) and putting across the political and social agenda of its side.

There are also Assets, which are a subclass of combat unit. These represent small groups of specialist troops or equipment that normally operate in support of Combat Units, to give them special temporary abilities. They are marked with an icon and a notation of how they affect the Ratings of units they are stacked with.

Paramilitary combat units (Militia, Police, Guerrilla, Non-State Militia and Criminal) are shown with an icon of an armed man. Regular combat units (regular troops, Main Force guerrillas, Foreign units, all Assets) are shown with a “NATO box” symbol or a picture of a piece of equipment.

Grant: What is the purpose of Infrastructure Units and can you give us a few examples to illustrate the purpose?

Brian: These units represent local political and administrative authorities (either the national government, or the “shadow” Insurgent government) and also immovable environmental features or improvements that support operations (e.g. training facilities, schools, wells, barracks, safe houses, weapons or food caches, tunnels). They are needed for several purposes: to give the Insurgent player a place to deploy his reorganized units; and for both sides to recruit or promote Militia, to help Areas recover from being Terrorized, and to gain Victory Points through control of the civilian population.

Grant: How do Attacks work and how do fights get concluded?

Brian: Either player may do this. A given stack may Attack one enemy stack of Combat Units that is “at large” in the same Area (that is, not in the Underground Box). A stack may be Attacked any number of times during an Operations Phase.

• The Government player may not Attack a stack unless it has at least one revealed (face up) Insurgent unit or Asset in it.

• The performing player will indicate a given stack in the Area, declare the mission and the enemy stack to be Attacked, and expend the required Task Point. If attacking, the Insurgent player will reveal any units and Assets in his stack used to affect the Attack (turn them face up). Both players simultaneously play one Chance Chit.

• The players compare their respective totals of Troop Ratings in the stack (which may be altered by any Assets present), plus the respective Troop Ratings of chits played. (If either player expends an Intelligence Advantage chit at the same time, he uses the highest of the three Ratings on the chit instead of the chit’s TR.)

• The player being Attacked also adds the Terrain Modifier of the Area to his total.

• The player with the smaller total is the loser and must inflict a number of Hits on his units equal to the DIFFERENCE between the totals of the Troop Ratings among the Combat Units and Assets used (ignore the chits). Depending on the composition of the stack, this will be a combination of Disrupting paramilitary units and placing Hit markers on regular units (which reduces their Ratings). The player must also deduct 1 TP for each Disrupted unit (this represents temporary damage to his command and control networks, use of resources to extricate a defeated force or treat casualties, emergency reinforcements or replacements, replenish supplies etc.).

• The player with the larger total is the winner and must inflict a number of Hits on his units equal to the DIFFERENCE between the Troop Ratings of the Chance Chits played (ignore the units). Subtract the smaller Troop Rating of the two Chits from the larger (it doesn’t matter who played which). As above, this will be a combination of Disrupting paramilitary units and placing Hit markers on regular units. The player must also deduct 1 TP for each Disrupted unit.

• If there is a tie between the two totals, the fighting is inconclusive – nothing happens.

• If a player Disrupted all units in his stack, all Assets in the stack are also automatically Disrupted , and if there remains a number of Hits to be made up that is greater than the Area’s Population Number, then the Area is Terrorized.

Example: An Insurgent stack of two Guerrillas (both 4-2-2) performs an Attack mission against a stack of one Police unit (2-2-1) in an Area with a Terrain Modifier of +2 and a Population Number of 2. The Insurgent player plays a Chance Chit with a TR of 2, the Government plays one with a value of 1. The two totals are 6 (2+2+2) to 5 (2+2+1). The Government has the smaller total so he is the loser. The difference in player TR totals among the CUs used is (4-2=) 2, so the Government player must inflict 2 Hits on his units. He Disrupts the Police unit and deducts 1 TP. This leaves 1 Hit to be made up but this is less than the Area’s Population Number of 2, so the Area is not Terrorized. The Insurgent has the larger overall total so he is the winner. The difference in Troop Ratings on the chits is (2-1=) 1. He Disrupts one of the Guerrillas and deducts 1 TP.

Grant: What is Foreign Firepower Advantage and why is this included?

Brian: Foreign troops have access to heavy weapons, artillery or air support assets not otherwise shown in the game. Any stack with a Foreign Combat Unit in it that is involved in an Attack (either performing one or defending against one) may play TWO Chance Chits if the Government player wishes. Each Chit adds its TR to the total. If the Government player is the one with the higher total, use the lower Troop Rating of the two chits when calculating Hits he must take. Foreign Combat Units are Disrupted last. This was a simple way to show the firepower and logistical advantages that professional armies and elite troops have.

Grant: How do Ambushes work? How do you make this type of attack advantageous in the design?

Brian: An Ambush is a type of Attack where the Insurgent can target a single Government unit within a stack for attack.

The Insurgent player compares the total of all Intelligence Ratings in the Ambushing stack plus any effective Assets plus the Terrain Modifier of the Area, to the total of the Troop Ratings of the Ambushed Combat Unit and the Chance Chit. (If the player expends an Intelligence Advantage chit at the same time, he doubles the Terrain Modifier of the Area.) So this gives the Insurgent a considerable advantage: their Intelligence Ratings are normally higher, and Ambushes are more effective in difficult terrain (and the modifier is applied to the ambusher, not the ambushee). Casualties are based only on the DIFFERENCE between the totals of the Troop Ratings among the Combat Units and Assets used (subtract the smaller total from the larger, no matter who the totals belong to; ignore the chits and Terrain Modifier). While the Insurgent player may not play a Chance Chit in an Ambush (he adds only the Terrain Modifier), none of his units are Disrupted if he has the larger total; also, Ambushes do not cause Terror.

Example: In an Area with a Terrain Modifier of +2, an Insurgent stack of two Guerrillas (both 4-2-2) performs an Ambush mission against a stack of one Militia (2-(1)-(1) and one Dispersed mode CBT unit (1!-3-0). The Insurgent chooses to Ambush the CBT unit. Government plays a Chance Chit with a TR value of 3. The two totals are 10 (4+4+2) to 6 (3+3). The Insurgent player had the higher total so he does not Disrupt any units. The difference of Troop Ratings is (4-3=) is 1, so the Government player places a “-1” Hit marker on the CBT unit.

Grant: Intimidation appears in the design as does Terror. How do these differ and why did you feel the need to make them different distinct actions?

Brian: Terror is a semi-random byproduct of combat. The player who caused the Terror may be penalized Victory Points, depending on his current Strategy. For as long as an Area is Terrorized, neither player may count it for population control Victory Points, nor may they build Infrastructure units, or recruit or promote Militia units there. An Area will recover from being Terrorized if one player performs a successful Remove Terror mission later in the game

Intimidation is a deliberate mission used by the Insurgent to target only the paramilitary forces (Militia and Police) in an Area. If they take too many casualties, the Area might become Terrorized into the bargain.

Grant: How does population of areas make a difference in the game? Is this mechanic generally needed to make a good counterinsurgency simulation?

Brian: Most counterinsurgency games acknowledge that “the people are the prize”; even people who like to talk wistfully about building pyramids of skulls accept that it’s nicer to have a few civvies left around to cart the (now headless) bodies away for you.

Each area on the map has a Population Number (Pop) from 0 (waste ground, desert or hilltops where no one decent lives) to 5 (a densely urban, built-up area). This measures the relative population density in the Area, and is important in deriving Victory Points (for controlling the local population and the Area’s Lines of Communication). Each Population Number represents a variable number of people, depending on the game. In the Maracas module it’s about 100,000 people per point, so the city as a whole is about 3 million people.

Control of the civilian population is usually one of the more important things to have or seek in the game. You get it by having more Infrastructure Units in the area than your opponent; how many Victory Points this gets you depends on your current Strategy card.

Grant: There are multiple Victory Conditions such as population control, Lines of Communication control, etc. Why is this needed?

Brian: During the game, both players will be working under one Strategy or another, representing the overall direction, plan, or priority of effort that they have been given by the higher authorities that they report to. Game modules offer four possible Strategies for each side, with variable player rewards and punishments for scoring Victory Points (VP).

So for example, in the Maracas module the Government player might be using “Counterinsurgency”, which will give him the most VP for disrupting enemy Infrastructure and paramilitary units, and punish him if he causes Terror in an area. Another time he might be using “Control Key Territory”, which gives him greater rewards for controlling Population and Lines of Communication, and nothing for eliminating enemy combat units.

Grant: What is Appeal to Authority and how does it work?

Brian: In their role as local commanders, players may appeal to the capricious and seemingly vindictive higher echelon that commands them for additional resources to fight the battle. In this Segment at the end of the turn, a player may (but doesn’t have to) draw one Chance Chit randomly from the Randomizer. This is “his” Chit. Then he draws a second Chit randomly to represent the reaction of “Headquarters”, and compares the three ratings on two Chits:

• Intelligence Rating: If the Rating on “his” Chit is higher, the player’s TP MAX goes up by the difference between the two Ratings (it may exceed the number specified at the beginning of the game). If the Rating on the “Headquarters” Chit is higher, his TP MAX goes down by the difference. No change if tied.

• Troop Rating: If the Rating on “his” Chit is higher, the player gains one regular unit or two Assets: add it to the Available section of the Unit Box (if Government, choose randomly among the Combat Units or Assets available: if no domestic Combat Units or Assets are available, he may choose Foreign ones). If the Rating on the “Headquarters” Chit is higher, one regular unit or Asset is removed from the game (player’s choice of which, from either the regular units on the map or in either section of his Unit Box). No effect if there is a tie.

• CIMIC Rating: If the Rating on “his” Chit is higher, the player may change his Strategy to one of his choice (he may also opt to leave it as it is). If the Rating on the “Headquarters” Chit is higher, then he picks a new strategy randomly from those available (so he may end up with no change after all!).

• Finally, the lowest of the three Ratings on the “Headquarters” Chit is the minimum number of turns that must elapse before the player can again make an Appeal to Authority. (You can’t bug the boss for a raise every week.)

Grant: What Special rules are included in the system rules? Why are these important to your vision?

Brian: The core rules contain 18 optional variations on play, from “Accidental Guerrillas” (if Government Terrorizes an area, they create insurgent Militia there) to “Xenophobic Locals” (Areas where Foreign Combat Units or Assets are present will have the Government’s VP award for Population Control halved).

One of my favourites is “Strategic Switcheroo”. At the beginning of the game, each player will secretly choose a Strategy at random for themselves to use, and one for the enemy that will be the “true” Strategy that will earn him Victory Points throughout the game. During the game, both players will record both their own Victory Points according to their current Strategy, and the enemy’s Victory Points according to his “true” Strategy (which, for simplicity, does not change during the game). When one player declares that he has sufficient Victory Points to win the scenario, play stops and the two players reveal each other’s “true” Strategy and Victory Point level. The winner of the scenario is the one with the higher “true” Victory Point level. What I’m attempting here is to show the disconnects between formal doctrine and direction (what is thought to be needed), experience (which can be just as misleading) and what actually works. Not knowing exactly how to win is a frustrating experience, but one that is typical of actual field commanders – on both sides – in an insurgency.

Grant: The first game in the series is called Maracas. Never heard of it. Where is this setting? Why start the series in this manner with a fictitious city and fictitious insurgency?

Brian: Maracas is the fictional capital of the equally fictional nation of Virtualia, and is a place where I have set some of my other games – notably Caudillo, a free card game on filling the power vacuum left by the untimely departure of the charismatic strongman leader Jesus Shaves.

I offered all four modules at once to Hollandspiele and asked them to start with Maracas, because I wanted to have a game out there that focused on urban irregular warfare.

Grant: What are the different Assets available to both sides?

Brian: In the Maracas module the Government player has a choice of:

Heavy Weapons, A-Team, Engineer Detachment, Psywar Cadres, sensors and drones, Informer networks, and Combined Intelligence Teams.

And the Insurgent player:

Double Agents, Heavy Weapons, IED Cell, Suicide Bombers, Cadres, Dummies, and Command Nodes.

Grant: How does this first game in the series set the tone and what can we expect from future iterations?

Brian: Maracas was actually the last of the four modules I designed. I asked Hollandspiele to put it out first, and even offered it on my website for free print and play (I think fewer than 100 people have had a look), because I wanted something of mine out there on modern urban irregular warfare.

As I said, the other three modules are from past conflicts and are more or less rural insurgencies. Some of the items they feature include:

Mascara: Insurgent supply units running through to the coast, airmobility, random terror, population resettlement

Binh Dinh: Agent Orange, airmobility, monsoon rains, the Phoenix program, US and South Korean forces

Kandahar: ISAF forces under incomplete player control, airmobility, non-state militias, Criminal elements

Grant: This game seems to focus on mega cities. Why is this important and how did you use this as the foundation for the system?

Brian: I have designed a lot of games on irregular warfare, and some of them are about irregular warfare in large cities (Tupamaro, Operation Whirlwind, Nights of Fire and now Maracas). I think it’s crucial to study this form of conflict.

In 2013 David Kilcullen, the noted writer on counterinsurgency, wrote an important book called Out of the Mountains. He articulated very well what I had always known, and had not forgotten in my plans for future designs:

In 2013 David Kilcullen, the noted writer on counterinsurgency, wrote an important book called Out of the Mountains. He articulated very well what I had always known, and had not forgotten in my plans for future designs:

• Most of the world’s population now lives in littoral cities, many of them “megacities” of 10 million or more.

• Increasing crowding, wealth inequality, strains on resources and infrastructure and climate change make it more and more likely that there will be widespread disorder and insurgent violence in these cities.

• Governments of whatever stripe or structure must anticipate this development, or they risk becoming failed states.

The nature of fighting in a densely populated area with elaborate social and physical infrastructure is partly reflected in the addition of several concepts for this module:

• Quick Reaction Force: this reflects the ability of the security forces to keep some units and Assets in readiness for anticipated action by insurgents, although their being withheld from the map means they will not affect the enemy until they are actually committed.

• Sabotage: the Insurgent player will find it relatively easy to interfere with the services and civic functions the civilian population expects the government to provide, so undermining the latter’s legitimacy. The Government player will have to expend time and resources to repair this damage.

• Informer networks: a densely populated and active city affords many opportunities for casual surveillance of the civilian population. Players can assume that informer networks already exist in much of the city to some extent to help the Insurgent player. The Government player will get random chances to create such networks during play, though their Informers are vulnerable to being terminated by Intimidate missions.

• Command Nodes and identifier chits: insurgent movements often rely on particularly intelligent, dynamic or inspiring individuals to lead and organize them. In the game these are shown as Command Node Assets. Their effects are to give the Insurgent player extra Task Points at the beginning of each turn, and therefore to enable the player to squeeze more out of their TP Allotment during the turn. However, their heightened visibility and activity may allow the Government player to track and identify them, and their loss will affect the overall health of the Insurgent’s command and control system (shown abstractly by the TP Allotment).

• Non-State Actors: the Terror game mechanic shows how normal life breaks down in a state of civil disorder and chronic if spasmodic violence. The Non-State Militia and Criminal factions show that non-governmental forces will arise to fill the vacuum of broken social order and absent law enforcement, in the form of local authority figures or gang warlords (who is which depends on your point of view, I guess).

• Objective Points: Some map Areas will contain Objective Points, features that are especially important or significant for economic or psychological reasons (e.g. The Docks, or the highly symbolic “Plaza 24 Octubre”). The Government player may “guard” them, and the Insurgent player may conduct Attack missions (though this activity is resolved through an Attack mission, it does not necessarily mean that the Insurgent is using violent means: for example, the attack could be a strike at the docks, or staging of a spectacular demonstration at the Plaza.) The Insurgent player may score an additional reward as described by their current Strategy if they do this.

Grant: What does the design do really well? What are you most pleased with in the design?

Brian: My favourite parts of the system are the Chance Chits and the relatively uncomplicated nature of the game. There are a lot of parts but not a lot of math, and while the rules may be a tad long they are chatty and introduce some uncommon concepts.

Grant: What is the plan for release of the game? What about the other games in the series?

Brian: Hollandspiele will have the Maracas module out in August possibly, followed by Binh Dinh. The Algerian and Afghanistan modules should follow in 2020.

Grant: You are always into something. What else are you working on in your spare time?

Brian: I don’t have a lot of spare time right now because my day job is going through an intense phase that will last a year or more. But:

China’s War: a GMT COIN system game on China 1937-41, for four factions (Japanese, Communists, Guomindang – Central and ex-Warlords). It has some different emphases in its game mechanics and I think people will like it.

Strongman: a drastic redesign of Caudillo.

Squares of the City and

Virtualia II Electric Boogaloo: Two semi-abstract games on urban conflict situations – inspired by the reading I’ve been doing lately on intelligence and asymmetric conflict in cities. They’re now in about “beta state”: roughed in, with rules mostly complete, lacking only some assembly and playtesting to tweak them into a more useful state than they are now. I will likely release these for free print and play, and through BTR Games in the near future, as cheap handmade artifacts with common components. It’s one way to reduce the large number of “game bits” I have acquired in years of thrifting (e.g. I rigged the component count of Virtualia II so that I can get three sets out of one copy of RISK).

I really appreciate your time in covering this series and taking a look at some of your thoughts on urban warfare and the megacity. I really learn a lot from your games and appreciate the depth that you include for those that are interested. As Brian said, the first volume of The District Commander Series Maracas should be available for purchase from Hollandspiele games in August.

-Grant

Thanks Grant! Always a pleasure to answer your questions.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure Brian. I’ll be back with you soon…I’m sure.

LikeLike

I hope so, but with only four projects on the cook right now it appears I’m slowing down….

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree that imperfect (at best) information is greatly under-represented in most game designs, and I applaud that focus here. I think the insights gained from operating in that environment is usually much greater than provided by high levels of detail, but a God-like view.

LikeLike

Yes, absolutely. I would have liked to have gone a lot further down this road with these designs, especially the urban module, but you have to keep it somewhat playable because people are easily frustrated.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great interview as usual, Grant!

And wow, if you guys could come out here to Bottoscon, I would definitely be there the full weekend.

I’ll probably be there anyway because I think it would be a great way to finally get some wargaming in.

LikeLike

Note: In May 2020 the mechanisms for Ambush and Intimidation were changed to nerf their effect somewhat.

LikeLike

Players Aid, PLEASE do a video on this!

LikeLike