A couple of years ago, we had the chance to play and do a preview video for a new series called Conflict of Wills from a new publisher at the time in Catastrophe Games. The first game in the series was called Judean Hammer designed by Robin David and was a very interesting and unique card driven area control game. Now, this series is being expanded by a few new designers (Tim Uren and Nick Porter) into a game called Arabian Struggle covering the conflict for the Arabian Peninsula in the early 20th century. We reached out to Tim and Nick and they were glad to answer our questions.

Grant: Tim and Nick, welcome to our blog. First off please tell us a little about yourselves. What are your hobbies? What’s your day job?

Tim and Nick: Hello Grant.

Tim’s now retired after nearly 30 years in the military and a few years running his own company. As well as games, he plays bass guitar in his band Flyover States, which specializes in obscure Americana – hence the band’s name. If you enjoy songs about evil trains from Harrisburg or waking up handcuffed to a fence in Mississippi, Flyover States has it covered.

Nick started out as a working archaeologist and historian, but found himself needing to ‘earn money’ to ‘feed his family’, so now works in financial services. He has been a life long wargamer, lucky enough to meet and game with the likes of Neville Dickinson, founder of MiniFigs in his youth.

Grant: What motivated you to break into game design? What have you enjoyed most about the experience thus far?

Tim and Nick: We’ve both been playing games, including a fair few war games, for decades. We also share interests, both academic and professional, in the use of games to simulate and better understand history, economics, conflict and so on. So we’ve had many conversations about game systems we enjoyed and respected (not necessarily the same thing) and have developed some pretty strong and fairly well informed views. This leads to rules tinkering and then full-on design. Tim’s early designs were workmanlike, doctrinally accurate, but so very dull…zzz. Nick’s designs tended towards extreme diceyness, rumbling like the thunder of wildebeest hooves across the veldt…

So we’d experienced both good games from others and our own design failures when we started discussing the potential of Nick’s Masters thesis as a game. Our first brainstorming session (in 2016) was helped immeasurably by a number of excellent IPA’s at one of Lisbon’s finest micro-breweries. We enjoyed that…. But we also identified some of the key points that could make an actually fun game, and made a few key decisions that have anchored the whole project since; more later.

But probably the single best experience was whilst launching Arabian Struggle at Punched Con in Coventry. A young man stopped by our booth and immediately identified the game setting and subject from the map and counters; it turns out that he was from Dubai. One game later, he delighted us by saying that he’d hugely enjoyed playing a game where Arabs were the central protagonists; apparently very unusual in games designed by westerners.

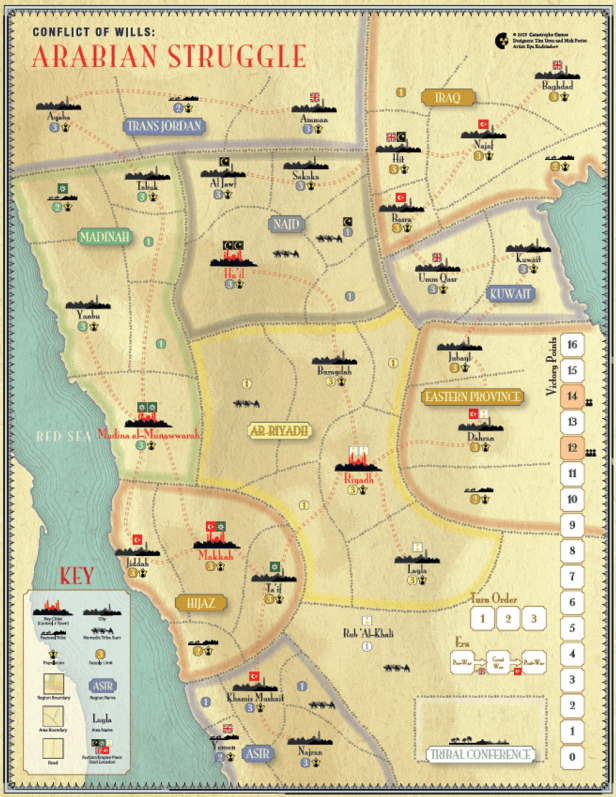

Grant: What is your upcoming game Arabian Struggle about?

Tim and Nick: It’s about the conflicts associated with the unification of the Arabian Peninsula in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. More generally, it’s a card driven irregular conflict game with a dash of area control.

Grant: Why was this a subject that drew your interest?

Tim and Nick: From a historical perspective, it’s an important slice of modern history, but often under-appreciated. The Saudi victory and their adherence to Wahhabism has substantially affected the development of modern Arabia, while the effects of external actors’ decisions (for example, British decisions at the 1920 Cairo conference) are still playing out to this day in the Middle East.

From a game perspective, it had a number of features that looked intriguing. It was multi-factional, had a definite story arc (we think that the three eras play rather differently, especially if you use the historical variant), and it was a finely balanced yet very swingy conflict.

Finally, of course, it’s an under-gamed subject. We found only one other game that addresses it directly – Rise of the House of Saud – and that’s approaching 40 years old.

Grant: What is your design goal with the game?

Tim and Nick: We wanted a game that was brisk (playable within 90 minutes or so), stabby (emphasized player interaction) but also thematic (provided a reasonable historical ‘feel’). But most importantly, we wanted it to be fun; it’s primarily a game for enjoyment.

Grant: What sources did you consult about the details of the history? What one must read source would you recommend?

Tim and Nick: Nick was the historical lead for this project. His primary sources were:

British Library Collections British Library Asian & African Studies – Foreign Office Colonial Papers Collections – Ibn Saud (Various)

St Anthony’s College Middle East Centre Private Papers of Glubb and Philby, India Office Papers

National Records Office, Kew AIR 5/477 to AIR10/1839

Listing his secondary sources would run to several pages, so this is hugely abbreviated and focusses mostly on easily obtainable books and articles. Useful introductions for general reading are in bold:

Alangari, Haifa The Struggle for Power in Arabia Ibn Saud, Hussein and Great Britain 1914-1924 (Garnet Publishing, Reading, 1998)

Al-Rasheed, Madawi A History of Saudi Arabia 2nd Edition (Cambridge 2010)

Al-Rasheed, Madawi Politics in an Arabian Oasis: The Rashidi Tribal Dynasty (New York 1998)

Al-Semawi, MN The Birth of Terrorism in the Middle East, Muhammed Bin Abed al-Wahab, Wahhabism, and the alliance with the ibn Saud tribe (Michigan 2013)

Askar H. al-Enaszy The Creation of Saudi Arabia Ibn Saud and British Imperial Policy, 1914 – 1927 (Abingdon, Routledge, 2006)

Barr, James A line in the sand Britain, France and the struggle that shaped the Middle East (London 2011)

Brown, Malcolm Ed. T.E.Lawrence in War and Peace. The Mlilitary writings of Lawrence of Arabia An Anthology (Greenhill, London, 2005)

Faulkner, Neil Lawrence of Arabia’s War The Arabs, the British and the remaking of the Middle East in WW1 (New Haven, Yale University Press, 2016)

McNamara, R The Makers of the Modern Middle East (London 2011)

J. DeLong-Bas, N Wahhabi Islam: From Revival and Reform to Global Jihad (Oxford 2004)

Khoury, P & Kostiner, J Tribes and State Formation in the Middle East (University of California Press, Berkley, 1990)

Kostiner, Joseph The Making of Saudi Arabia 1916-1936 From Chieftaincy to Monarchical State (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1993)

Lacey, Robert. The Kingdom (Harcourt, Brabce & Janowicz, New York & London, 1980)

Lawrence, T.E. Seven Pillars of Wisdom (Jonathan Cape, London 1935 [Penguin Classics 2000])

Philby, Harry St.J Bridger Arabia of the Wahhabis 2nd Edition (Frank Cass, London, 1977 [ALCS E-Book 2016])

Rogan, Eugene The Fall of the Ottomans; The Great War in the Middle East 1914-1920 (London 2015)

Rogan Eugene The Arabs: A History (London 2009)

Sander, Nestor Ibn Saud King by Conquest (Selwa Press, St Vista, 2009)

Thesiger, Wilfred Arabian Sands (London 1959 [2007 penguin imprint])

Grant: How was the experience of designing a game in an established system?

Tim and Nick: Very straight forward and positive. Our early ideas were a bit more bottom up and simulationist; for example, we had separate pieces for field armies, militia and individual leaders, and different mechanisms for different types of combat and control.

But Robin David’s Conflict of Wills System (first seen in Judean Hammer), was a superb fit, well suited to irregular conflict. It also shifted us to a more abstract, top down, design for effect approach. The excellent fit of Conflict of Wills and our prior design work meant that once we got the go ahead from Catastrophe Games, it took only a weekend to produce the first rules draft, which has changed surprisingly little since.

Grant: What elements did you feel needed to be changed to better capture the history of this struggle?

Tim and Nick: The key change was that Judean Hammer had two factions, but we wanted several. Nick was determined that we should have three Arab factions, but we went through a number of iterations for the external actors, eventually settling on two non-player factions, the Ottoman and British Empires. This latter point is important; we wanted the Arab factions to be the focus of the game play, not the Empires, so making the Empires NPC’s reinforced this design aim.

Grant: What elements from the struggle for control of Arabia were important to model in the game?

Tim and Nick: There were quite a number! But the key ones include:

The role of discussion and negotiation as well as conflict, mostly represented by the Tribal Conference mechanism.

The distinction between ‘battle’ and ‘raiding’ in warfare.

The influence of external actors.

The mobility of part of the population – the bedouin (nomads).

But perhaps most importantly, we wanted to reflect that the historical outcome was far from pre-ordained! Historical examination shows that the key leaders took extraordinary risks in a very unstable environment – we wanted a game that felt swingy, dangerous and full of caprice.

Grant: What are the three playable factions represented in the game?

Tim and Nick: The House of Saud (the Saudis) – the historical victors, led by the wily desert fighter Abdul Aziz.

The House of Hashim (the Hashemites) – eventual rulers of Iraq (for a while) and Jordan (to the present day).

The House of Rashid (the Rasheedis) – undone by a combination of internal feuding, the collapse of their Ottoman allies, and British imperial policing.

Grant: What different types of cards are included in the game? How does the game use the cards?

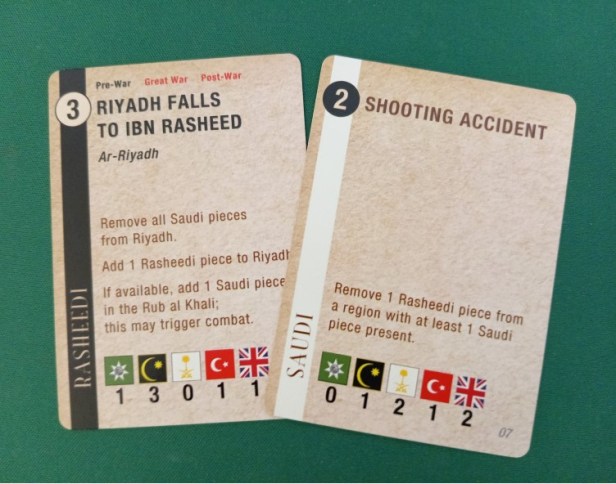

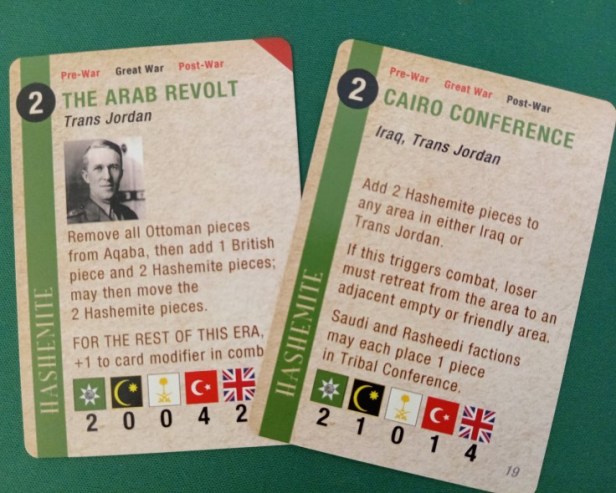

Tim and Nick: There’s one deck of 48 cards, in four suits of 12 each (one suit per faction, plus neutral). They are pretty typical of a card driven game. Generally you can play them for points, to augment or move your forces, or for the event (if playable in that era). When you play a card of an opponent’s suit, you must offer them the chance to play the event. Cards used for the event are permanently removed from the game. This last point can be important, as the cards are also used for RNG during combat (more later). A faction’s best combat RNG are on their own suit’s cards, naturally. So decide; event now or improved future combat odds?

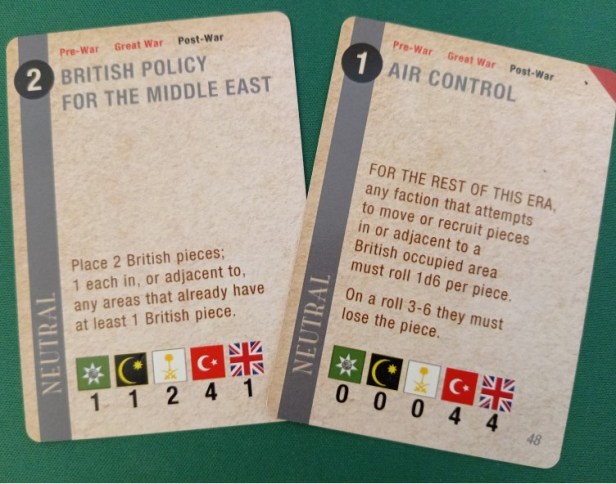

Grant: Can you show us a few examples of cards and explain their use?

Tim and Nick: Here’s a few pictures, along with their background:

02. Wahab. Mohammed ibn Wahab (Wahhab) was an 18th Century Muslim cleric from central Arabia, whose austere, fundamentalist teachings were adopted by the Saudi family. The fortunes of Wahabism and the Saudi family have been closely coupled ever since, and have had a significant influence on the development of the modern Saudi state.

01. Ikhwan. The Ikhwan were nomadic tribesmen who converted to Wahabism (Wahhabism) and provided significant military support to the Saudis. Although effective desert raiders and occasional missionaries (card 10, Ikhwan Missionaries), they were a double edged weapon. During the conflict, their tendency to murder prisoners, including women and children, may have hardened resistance against the Saudis (card 29, Ikhwan Atrocities). After the conflict, they attempted to overthrow Abdul Aziz on the basis that his adherence to Wahabism was insufficiently austere and rigorous. After this rebellion was put down in 1929, the remaining Ikhwan became the core of the Saudi National Guard.

25. Riyadh Falls to Ibn Rasheed. Lead by their Emir, Talal bin Abdullah, the Rasheedis of Ha’il removed the Saudis from power in the Nejd in 1865, exiling the Saudis to Kuwait. Talal died in 1868 in a ‘shooting accident’ (card 07, Shooting Accident). Given the blood thirsty nature of Rasheedi family disputes, the ‘accident’ was possibly pre-determined… Historically, these are the earliest distinct events in Arabian Struggle. Abdul Aziz retook Riyadh in 1902.

21. The Arab Revolt. Starting in 1916, the Arab Revolt was a Hashemite-led, British-supported (card 18, Letters to McMahon), rebellion against the Ottoman Empire in Arabia, with the aim of founding an independent Arab kingdom. It successfully cleared the Ottomans from the Hejaz and beyond by 1918. Subsequently, however, the British, having signed the Sykes-Picot Agreement with the French, reneged on their promise to support an independent Arab state. The card pictures TE Lawrence, a British officer who worked closely with the Hashemites and later wrote ‘Seven Pillars of Wisdom’ about his experiences.

19. Cairo Conference. Perhaps the most significant single event for the long term future of the Middle East, the British convened the Cairo Conference in 1921 to agree a plan for the allocation of previously Ottoman territories to Arab leaders. Heavily influenced by TE Lawrence, the Conference agreed that Turkish Mesopotamia would become Iraq, ruled by the Hashemite Prince Feisal, while his brother Prince Abdullah would rule Transjordan (now Jordan). Unfortunately, the new Iraq was a hodge-podge of Shi’ites, Sunnis and Kurds (with no separate homeland for the Kurds), while Palestine was split in two, with an aspiration to a new Jewish homeland (eventually Israel)…

48. Air Control. The first card we designed, and a core part of Nick’s Masters thesis. Following the Great War, the British successfully experimented with a new form of Imperial policing; control from the air. Notably, one of the RAF unit commanders was Arthur Harris, a WW1 Royal Flying Corps fighter ace and later commander of RAF Bomber Command through much of WW2. Playing this card for the event can have a startling effect on the board state, especially in concert with card 40, British Policy for the Middle East…

Grant: How is combat handled?

Tim and Nick: Combat is very much based on the Judean Hammer model. Base strength is pieces on the map plus any modifiers from previous cards. Flip the top card of the draw deck, add the appropriate RNG to each side, largest wins. Attacker wins ties! It pays to be aggressive…. Then there’s a roll for casualties, which can be brutal for the loser… we’re representing tribal desert warfare, after all? Finally, if any defenders survive, then the attackers must often retreat; this represents a raid, rather than a pitched battle.

Grant: What are some pointers for how best to go about control of areas?

Tim and Nick: Simplistically, always put two pieces in populated areas. That way, if you get attacked and lose, you have a 50:50 chance of surviving the casualty roll and converting your opponent’s victory into a mere raid. But you’ve only got 18 pieces, and card events make holding secure areas or front lines very hard. So more broadly, be opportunistic, be aggressive, ride the instability. More fun(ny) anyway?

Grant: What is the role of the Tribal Conference?

Tim and Nick: Thematically, it represents the role of discussion, negotiation and political/religious authority. Mechanically, it enables players to ditch a particularly harmful card (the event doesn’t trigger, so it has a similar function to the Space Race in Twilight Struggle) whilst having a chance to score a VP. There are about 10 cards whose events affect Tribal Conference. These lean slightly towards the Saudis, to reflect the way that their adoption of Wahhabism increased their religious and therefore political authority.

Grant: How are Victory Points scored?

Tim and Nick: There are three sources of victory points (VP). First, win a ‘great victory’, which requires winning a battle whilst clearing the area of enemy forces and also surviving the experience; 1 VP per great victory. Second, having the most influence in Tribal Conference; 1 VP at the end of each era, so maximum 3 per game. Finally, controlling the most population in each of the 9 scoring regions at the end of each era; 1 VP per region, so potentially 27 per game, although that’s extremely unlikely.

In general, VP are not easy to come by, in particular because ties for Tribal Conference and regions score nothing, but are fairly common. The Empires play a considerable passive role here, as they automatically control the population in their areas, regardless of the number of faction pieces. Most games that run full length score in the teens, with often only a few points between the factions. This was quite deliberate, as we wanted the game to be tight and to swing on small margins.

Grant: How is victory achieved?

Tim and Nick: Most VP at game end (end of the post-war era)! But there’s two early game end conditions:

One faction has scored 12 VP at the end of the first or second era. This implies that they are well on top; it’s a mercy kill for the losing players.

Control the 4 key cities at the end of any era. The 4 key cities are the holy cities of Mecca and Medinah, plus the faction capitals of Riyadh and Ha’il. This is the greatest victory possible. It’s very rare, but glorious.

We also distinguish between levels of victory based on VP differences between factions; petty sheikhdoms, monarchy, caliphate.

Grant: What are you most pleased about with the outcome of the design?

Tim and Nick: To us, it feels right thematically. It’s got some interesting and important history embedded in the cards. It’s fun to play, and although unstable, it’s reasonably balanced. The three player game tends to generate table chat and fleeting pragmatic alliances. Because it’s an unusual subject, we hope that people will find it an engaging introduction to some of the key players and events in this region’s history.

Grant: What type of experience does the game create for players?

Tim and Nick: To a certain extent, that depends on the players. If they are all risk averse and hunker down in their homelands, it can go a bit attritional and is likely to end with very small differences in VP – a ‘petty sheikhdoms’ outcome. But with even a modicum of boldness, it can come alive and you’ll see substantial swings of fortune. We much prefer the latter approach. It’s funnier, and because the game has a fair amount of luck with cards and dice, a low risk approach can come undone anyway. Finally, of course, it’s a pretty quick game, with most games well under 90 minutes, so we think that its designed-in instability and capriciousness is acceptable in that context.

Grant: What other designs are you currently working on?

Tim and Nick: Tim’s got some gigs with Flyover States coming up, so he’s mostly working on his bass lines. Nick’s working with the Devizes war-game group on some rules for battles of the War of the Spanish Succession. We’ve had a few conversations about the Monmouth Rebellion and Glorious Revolution (17th Century Kingdoms of Scotland, England and Ireland) being a good candidate for the Conflict of Wills System, but it’ll have to wait until we’ve a little more spare time.

But mostly we’re very excited about Tim Densham’s upcoming tactical fog of war game system. It’s very playable, very tense and makes a lot of sense to anyone with military experience. One of the problems with war games generally is that that they give the players both too much information and too much agency. Tim’s game addresses both with some beautiful, elegant mechanisms, whilst remaining playable and great fun. We really like it and hope to be involved in its play testing (Tim? Hello?)

Thank you for your time in answering our questions Tim and Nick. It is much appreciated! I had the opportunity to play the game with the development team, including owner Tim Densham and Jim, along with the guys from Legendary Tactics during Gen Con at my place. We had a great time and the game plays in about 90 minutes (quicker once you get the rules down and know the cards a bit better). The game play is fast and furious and it has many of the tenants of a Card Driven Game where players play the cards for the printed event if they are aligned with your faction or for the Operations Points if not and then the event will go off for the aligned faction. The unique elements to the game were two fold. You are not only competing against the other 2 players in the game, trying to come out on top among the various Arab factions, but you are also fighting against the convulsing and dying Ottoman Empire and their forces as well as the British as they come into the region looking to exert their control. Secondly, as an area control game, you are desperately fighting to control as many areas as possible to score Victory Points at the end of each round. But, there is a unique element of moving nomadic groups around the board to increase your population in areas you control which will give you more weight in the areas and push you over the top for ultimate control. Really slick little game and I had a great time. The LT guys also enjoyed it and even though Randy is not a big fan of CDG’s he also felt the game was very solid.

If you are interested in Conflict of Wills: Arabian Struggle, you can pre-order a copy for $50.00 from the Catastrophe Games website at the following link: https://catastrophegames.net/arabian-struggle/

-Grant

Looking forward to this. Not only is Judean Hammer interesting, Rise of the House of Sa’ud was not well done (but it was a brave act to publish anything like this at the time!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

What is this O Canada design I’ve heard about?

LikeLike

O Canada: I worked on this one during lockdown.

Essentially a reboot of the old SPI game Canadian ‘Civil War’ via the GMT COIN system – a completely non-kinetic struggle fought on two levels for 4 players representing factional tendencies in Canadian politics, in 4 scenarios from the 1950s to the near future.

Features a deck of Event Cards with jokes comprehensible only to Canadians.

This will likely be my last essay in the GMT COIN system; like Volko Ruhnke said in a recent interview, I am moving on.

4 players, area map, ~150 pieces, 56 cards.

No solo system; get yourself some friends or be more patient with yourself.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Is it ready to be announced anytime soon?

LikeLike

I’ve mentioned it a few times on my blog; obviously no one is interested in publishing it formally and I find I don’t really care about doing it that way either.

My plan is to spiff up the graphics a bit and make it available as a cheap print-and-play, and sell a few hand-made copies at a price commensurate with time and materials consumed (I don’t own a Chinese factory so I would pay myself at least provincial minimum wage).

Maybe by the end of the year?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I would be interested in paying for one of those handmade (with love I am sure) copies where I paid a provincial minimum wage!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, it’s only fair… the absolute legal minimum one can be paid for their work.

So, that’s three copies to make up then.

I’ll let you know!

LikeLiked by 1 person