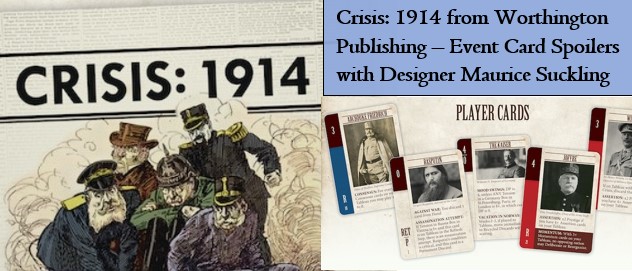

We became acquainted with Maurice Suckling with his game Freeman’s Farm 1777 from Worthington Publishing in 2019 and really enjoyed the mechanics and how they all came together to create an interactive and interesting look at the Battle of Saratoga during the American Revolution. Since that time, Maurice has designed several other games that have went on to successful Kickstarter campaigns including Hidden Strike: American Revolution, Chancellorsville 1863 and 1565 Siege of Malta. He is now working on a game that is tied to the buildup of tensions that led to the outbreak of The Great War called Crisis: 1914 from Worthington Publishing, which was successfully funded on Kickstarter this past summer. He has prepared a series of Event Card Spoilers for the game and we are hosting them here on the blog. These posts will share the cards basis in history as well as how they are used in the game.

If you are interested in ordering Crisis: 1914, you can pre-order a copy for $65.00 from the Worthington Publishing website at the following link: https://www.worthingtonpublishing.com/collection/crisis-1914-pre-order-this-game-will-not-ship-until-february-2024

Card #1 – Grigori Rasputin – Advisor to the Czar

Born in Siberia, Grigori Rasputin gradually gained a reputation throughout the region as a mystic and monk with miraculous power. Prior to World War I, he had used his charisma to ingratiate himself with the Russian royal family – and convinced Czarina Alexandra that he was the only one capable of healing her son, Alexei, of his hemophilia (Jarausch 2015, 110-111, Martel 2014, 34). His involvement with both Alexandra and Czar Nicholas II contributed to their withdrawal from political concerns, as well as their separation from Russian society more broadly (Martel 2014, 33-34); he himself predicted war would lead to the destruction of the Russian Empire and advised against Russian involvement (Albertini 1965b, 572n).

On July 13, 1914, Rasputin was the subject of a failed assassination attempt in his hometown of Pokrovskoye. The assailant, a woman named Khioniya Guseva, proved to be a devotee of Iliodor (Sergei Trufanov), a defrocked monk and rival of Rasputin. Following her arrest, she proclaimed, “I wish to remove from this world that false, infamous prophet who has led so many people astray, and who has falsely instructed the Czar on countless questions” (New York Times 1914a).

Card #2 – The Czar – Nicholas II, Czar of Russia

Although less mercurial than his imperial cousin in Germany, Czar Nicholas II was not exactly naturally inclined to matters of state. His early years on the throne were characterized by “extreme shyness and terror at the prospect of having to wield real authority,” but he never established a personal secretariat to assist with the trivial matters that found their way before him (Clark 2012, 175). Instead, he attempted to shoulder the entire workload alone, despite the fact that he would much rather have preferred to spend time in private away from the court (Martel 2014, 32-34).

During the July Crisis, Nicholas II emphasized his commitment to the idea of protecting Serbia, but his desire to have a direct hand in events often sowed confusion (McMeekin 2013, 163). After ordering a general mobilization on July 29th, he grew nervous, revised the order to a partial mobilization, and was then persuaded by Sazonov to almost immediately reinstate the original general mobilization (Ham 2013, 357-358).

Card #7 – Alexander Krivoshein – Minister of Agriculture

By July 1914, Alexander Krivoshein had become the most powerful figure in the Russian Council of Ministers and in this capacity led a “war party” that skewed simultaneously toward Francophilia and Germanophobia (Clark 2012, 474; McMeekin 2013, 53). He himself had cultivated a growing reputation as a Germanophobe, not least as a result of his years working alongside Peter Stolypin and through the development of multiple ties to nationalist causes in Russia (McMeekin 2013, 53-54; Clark 2012, 473). Needless to say, Krivoshein was a hawk when it came to taking action against Austria-Hungary and Germany, despite his acknowledgement that the Russian military had yet to recover from its losses in the Russo-Japanese War. He consequently advised the Council on July 24th to adopt “a firmer and more energetic attitude towards the unreasonable claims of the Central Powers” (Clark 2012, 474).

Card #15 – Nicholai Hartwig – Ambassador to Serbia

A long-time supporter of Serbia and “one of the most ardent pan-Slav sympathizers amongst imperial Russian diplomats” (Otte 2014, 129). Only a few months prior to the crisis, Hartwig had supported Nikola Pašić, the Serbian Prime Minister, against an attempted ultra-nationalist coup; in the wake of the assassinations, though, he cautioned the latter to act with restraint (Otte 2014, 33-34, 129-130).

Hartwig would ultimately die of a heart attack just under two weeks into the crisis on the night of July 10th – in the middle of a somewhat late-night conversation with Baron Wladimir Giesl. Despite the suspicious timing of his demise, as well as the rumors that began to spread immediately thereafter, it is worth noting that he was known to have “suffered from a serious heart ailment for a long time” (Joll 1984, 30; Otte 2014, 130).

If you missed the previous entries in the series, you can catch up on the posts to date by following the below links:

Series Introduction and General Mobilization Cards

If you are interested, we posted an interview with the designer and you can read that at the following link: https://theplayersaid.com/2023/07/12/interview-with-maurice-suckling-designer-of-crisis-1914-from-worthington-publishing-currently-on-kickstarter/

-Grant