Over the past couple of years, I have become acquainted with a newer Spanish wargame publisher called SNAFU Design. I first interviewed one of their partners and designer Marc Figueras in early 2021 on his new game called Ambon: Burning Sun & Little Seagulls. We next interviewed the incomparable Javier Romero for his design with SNAFU called Santander ’37. Then back to Marc with his Equatorial Clash game. These games are very cool and cover lesser gamed subjects so these are right up my alley. Recently, I saw where a newer designer named Ivan Prat was doing a new design for SNAFU in their Small Battles Series called 12 Hours of Maleme that takes a look at the German Airborne landings on Crete during World War II. I reached out to Ivan and he was gracious enough to answer our questions about the design.

Grant: First off Ivan please tell us a little about yourself. What are your hobbies? What’s your day job?

Ivan: Boardgaming has been my main hobby since I was 12. I remember playing Fief, from the Italian publisher International Team, and how it changed my vision about what games can accomplish in terms of narrative, interaction, treachery and sheer fun. None of the games I had previously played offered that experience. More games followed, mainly wargames, of International Team and from Avalon Hill, GDW and GMT. I also played a lot of roleplaying games through the 90’s like Rolemaster, Pendragon and Cyberpunk. I still play card games and roleplaying games but wargaming is the main course. As a side hobby, I play drums in a rock band with life-long friends just for the fun of it.

I studied Industrial Design and worked some time with design related jobs but my day job now is being a trainer in office applications mainly for unemployed people and sometimes for company employees.

Grant: What motivated you to break into game design? What have you enjoyed most about the experience thus far?

Ivan: I remember being told history in the classroom when I was around 13 and started to think about how a game on that subject would be. I wrote down many ideas but lost that paper afterwards.

Nearly 30 years later I wanted to prove to myself I was able to create a wargame, so I chose the setting – the Napoleonic invasion of Catalonia (or as we call it here “The War of the French”) – and the shape of the game: a two player point-to-point single-deck card-driven game. This game is not published – yet – but it got me into the design and production of 1714: The Case of the Catalans, a more political design than a wargame, published by Devir in Catalan and English and distributed by GMT.

At the beginning, what I enjoyed the most was the analysis that needed to be done beforehand, along with the briefing, so the process will become fluent and straightforward. The amount of decisions you need to make on the first steps of the design will shape the outcome, including what sensations you are trying to offer the players with the game.

But I’ve discovered what I really enjoy is seeing the players having fun with the game. That sensation struck me the first time I saw some real people (not play testers) laughing and arguing and backstabbing each other on the first plays of the Case of the Catalans once it was published.

Grant: What historical period does 12 Hours at Maleme cover?

Ivan: The game covers the first day of the German invasion of Crete, in May 1941. The battle for Crete lasted 13 days but its final outcome started to take shape when the Germans got a hold of the Maleme airfield. The first steps of the invasion were aimed at conquering an airfield from where they could start landing troops and equipment. The Maleme airfield was conquered on the first day of fighting and was crucial to the loss of the island. The game depicts that first day, hence the name “12 Hours”.

Grant: Why was this a subject that drew your interest?

Ivan: There is that strange thing about battles where people tend to be a fan of one or another, if being a fan of a battle is possible. In my case, the battle for Crete has always daunted me; the small island causing the sensation of a limited retreat and the enemy falling from the sky always impressed me.

When discussing what could make a good next installment in the SNAFU Small Battles Series and a friend proposed Maleme, I was all in.

Grant: What research did you do to get the details correct? What one must read source would you recommend?

Ivan: The sources are always open to debate, and usually just the choice of them will shape the game and its message (if it has one). In this case, I found no better book than Antony Beevor’s Crete: The Battle and the Resistance. In Battle for Crete by John Hall Spencer, there is a great amount of detail that I found useful too.

To get the details straight on German parachuting techniques, Ramon, my historian friend, offered me German Paratroops in WWII by Volkmar Kuhn and Luftwaffe Handbook by Alfred Price. Both were invaluable in shaping the drop mechanic and its effect on German troops.

And a source I particularly loved is 22 Battalion by Jim Henderson. A journal of the battalion, digitized by the Wellington Library of the Victoria University and available online.

Grant: This game is volume 4 in the Small Battles Series. What are the parameters of that series?

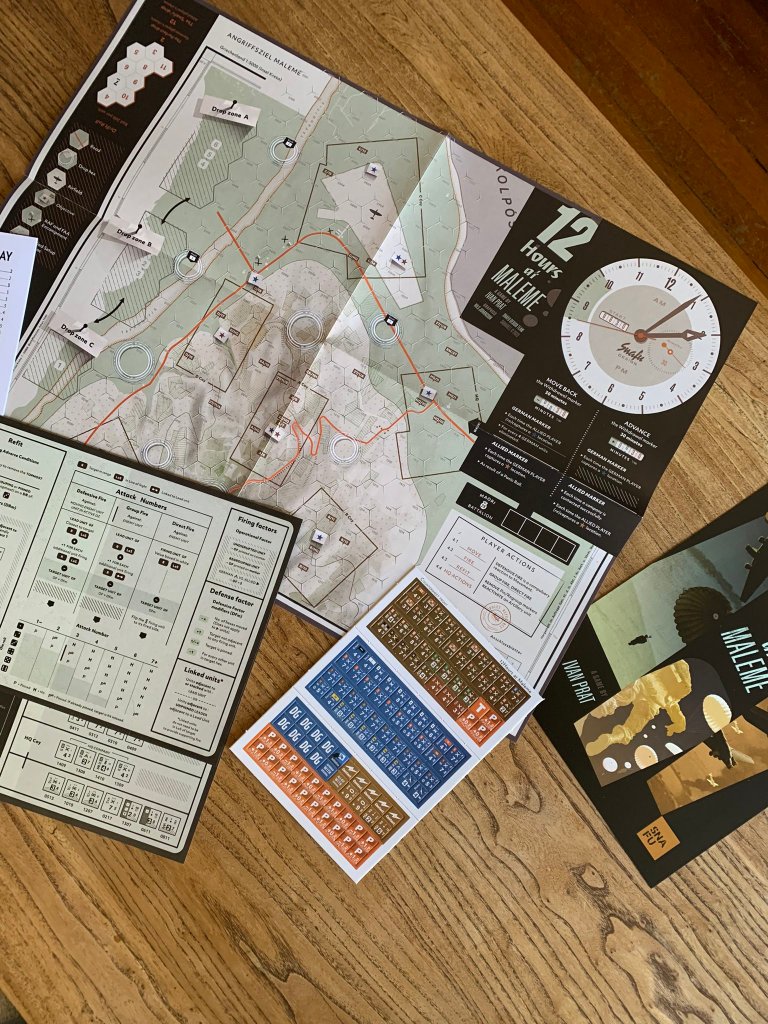

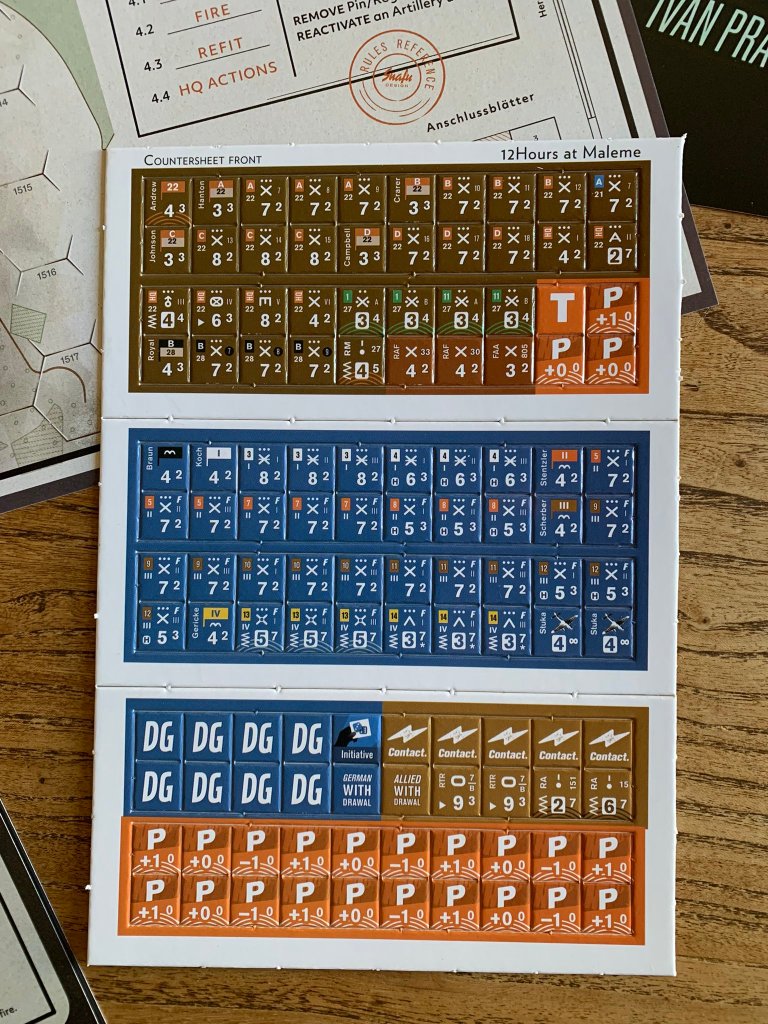

Ivan: These games are distributed in an A4 size ziplock and thus are a bit limited in the amount and size of the components. Usually they have a paper map between A2 and A3 and a countermix of maximum 120 counters. They have a minimum of 2 player aids (cover and back cover), a rulebook and don’t have cards.

On the theme side, we try to focus on less explored battles, as you can see from the first three games. Crete is a more travelled road in wargames but there was no tactical game focusing on one of the drops of the first day of the invasion.

Grant: Did you have any challenges with fitting this game into those parameters?

Ivan: The amount of counters available in a ziplock game has been a constraint in designing the game and caused us some extra thoughts to prevent players running out of informational counters, but this was the only challenge as I had in mind from the beginning to design a SNAFU Small Battles Series game.

Grant: What is the scale of the game and force structure of the units?

Ivan: As the game reproduces the first day of fight in the Maleme area, the turns had to represent something between one hour and fifteen minutes to keep the game playable in a couple of hours. The fight involved all the companies of the 22nd battalion, each one assigned to a specific area, so we needed to represent the companies at platoon level to allow the player a certain amount of maneuverability maintaining a low counter mix at the same time. The intended map was an A3 size, and we had to keep it balanced with the amount of units to be deployed there. We decided the size of the hexagons at 150 meters to allow enough movement options and to match the fire mechanic with the ranges of the firearms used in the battle.

Grant: What unique units are available to each side?

Ivan: There are plenty of unique units due to the nature of the defensive position and of the assault.

Among the Allies there are some units of RAF and FAA technicians, caught by the drop in the middle of their breakfast, two RA cannons which refused to open fire on the German soldiers for they had orders to fire at incoming ships only, and two Matilda tanks, hidden by Lt. Col. Leslie Andrew and released as a winning move only to break at their first maneuvering.

In the German ranks, there are Heavy Weapon units dropped along the gliders and paratroopers, some infantry and anti-tank cannons dropped on the west side of the Tavronitis River bed, out of range of New Zealanders fire, and two Stuka units that may be called upon to soften the defenders.

Grant: What area of Maleme does the board cover? What key features of prominent on the board?

Ivan: Basically the two objectives of the German assault: the airfield, on the northern part of the map, and the Hill 107 from where the 22nd Battalion was directed.

The game has no terrain features affecting movement or fire, as Hill 107 is a very gently slope and there are very few things that can hamper the line of sight.

Grant: What role does Hill 107 play for the Allied defense?

Ivan: In that place Lt. Col. Leslie Andrew planted his HQ as it is the highest point in the area. From there you can easily access the airfield, the Tavronitis River bed and the village of Pirgos. Besides, the two RA cannons were also placed there, and it is an area easy to defend. All this made Hill 107 a crucial objective for the Germans.

Grant: Who is the artist? How does his work contribute to your goal for the design?

Ivan: The artist is Nils Johansson, and it would be difficult to describe in a few words all the contributions he made to it. Not only did he provide a very beautiful and pleasant playing area and components, but he also acted as a developer helping us with the usability of the player aids and counters and how to connect the rules with the components. His use of historical sources, fonts and maps contributes to the immersion of the players, fulfilling completely the goal of every design, which is to encompass at the same level form and function.

Grant: When units are activated, what actions can they take?

Ivan: In 12 Hours at Maleme you activate just one unit and then decide if it has to move, fire or refit. Afterwards, your opponent will do the same, activating one unit or performing an HQ action.

When you decide to move a unit, you do it one hex at a time and check if the unit receives defensive fire, which is mandatory in this game. If the unit doesn’t get fired at or doesn’t receive a Hit or Pin result due to fire, it can continue moving.

When you want to fire with the activated unit, that unit may be supported with its adjacent units and leaders, forming a Fire Group. Some units, mainly artillery units, are capable of a Direct Fire where they can’t be supported by other units, but they disregard the defense of the attacked unit.

A refit activation allows the player to try to remove a condition present on the unit, such as a Regroup or a Pin.

Grant: What HQ actions are available? How do these HQ’s augment actions?

Ivan: The HQ actions are mainly about command and control and calling for reinforcements.

The Allies have some extra units entering as reinforcements via HQ actions, the most important being the Maori Battalion, actually a Company arriving from the West. The Allied player also has two Matilda tanks hidden near the airfield to be released without difficulty, the down part here being the poor state of maintenance of the tanks. But the most important HQ Action for the Allies is to try to contact the companies. This action is crucial to keep fighting, for the impossibility of contact was the historical cause of the loss of the airfield.

The German player has only two HQ Actions: to call for a Stuka to dive bomb an Allied position (can be done twice in a game) and the retrieval of the Initiative Token, a device capable of forcing a re-roll and reorganize (revive) a fallen platoon.

Grant; What is the anatomy of the counters?

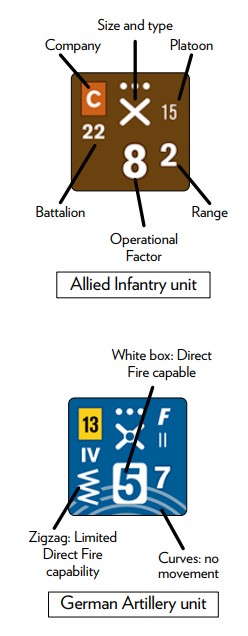

Ivan: One of the core design decisions was the units having only one number to be used as movement and fire capability. Thus, on a counter, there is a big number representing that Operational Factor (movement and fire) and a super index to represent the range in hexes. There is also a NATO symbol for the type of unit and some icons to indicate Heavy Weapons, Direct Fire capable or Immobile Unit. In addition, each unit has the information about its size, number and higher echelon.

Grant: How does combat work in the design?

Ivan: Combat in this game is defined as a Fire action, and it can be done in three different ways.

Defensive Fire is the mandatory fire each unit must endure if moving within range of enemy units.

Group Fire is the activation of a unit to fire at an enemy in range and can be supported by adjacent units.

Direct Fire is the firing of an artillery unit with no support and disregarding the Operational Factor of the attacked unit. That kind of fire “spends” the firing unit, and will need a refit action or wait until the end of the turn to be able to fire again.

The fire mechanic is the comparison of the Operational Factors of attacker and defender, adding a few modifiers to achieve a column number where to check the result with a single die roll. The fire mechanic needed to be very straightforward for in a single game there are hundreds of fire actions.

Grant: How does time advance? Why was this roll a 6 advance of the time added to the game?

Ivan: The length of the turn is variable, ending every time a 6 is rolled on a fire or refit action. If you have it, you may hand to your opponent the Initiative Token to cause a re-roll to try to lengthen the turn.

But this “6 rolled mechanic” is no addition, it was also one of the core decisions I made for this game. This decision was based on having no method of tracing which unit has been activated, as this is no area movement game, but mainly because I wanted to represent the uncertainty those soldiers faced that day.

On the German side, entering a battlefield via paradrop without complete intelligence on what is expected below is a fair amount of uncertainty.

On the Allied side, the inability to contact the other companies and thus incapable of gathering intelligence on the ongoing battle was the fatal uncertainty that led to the loss of their positions and the battle.

This perception on how the time passes differently whether you are winning or losing is also a side effect of this mechanic.

Grant: How many turns are in the game?

Ivan: Each turn represents 30 minutes. The first turn of the paradrop is 8:30 and there are four turns of paradropping. So at the 10:30 turn everyone is on land and the game will continue until the Time Marker hits the German or the Allied Withdrawal Marker, happening more or less around 18:30. So a typical game may last around 22 turns.

Grant: How do players achieve victory?

Ivan: Each side has a Withdrawal Marker placed by setup on the turn track, in the shape of a clock, at 6:00pm. As the game progresses, those markers may be advanced or delayed depending on various situations. When the Time Marker occupies the same turn as a withdrawal marker, that side withdraws from the battlefield and the opponent wins the game.

For the Allies, each German occupation of a brown star hex advances 30 minutes their withdrawal marker. Each company contacted delays 30 minutes that marker. In addition, each o’clock hour the Allied player must make a Panic Roll against the number of contacted companies; in the case of failure, his withdrawal advances 30 minutes.

For the Germans, each occupation of a blue star hex delays 30 minutes their withdrawal marker and every 4 dead units advances it 30 minutes.

Grant: Which side has the tougher time of meeting their objectives?

Ivan: It is a very asymmetric game and it is difficult to answer as every player, no matter which side was playing, felt there were having a tough time. It will depend on the location of your Withdrawal Marker. If you are winning (the Marker is placed later than your enemy’s) you will feel the turns are too long. If you are losing you will feel there is not enough time to achieve your goals.

It will also depend on your preferred style of playing. The German side has the pressure on, has to move boldly preventing at the same time too many losses. The Allied side is more static, has to move the units to achieve killing zones and be patient.

Grant: What type of an experience does the game create?

Ivan: As I said above, the perception of the passing of time was one of the things that came to me when I read the battalion’s journal and the variable intensity of the fight in different areas at different times of the day.

As the players activate their units in alternation, they never know exactly how many units they will be able to use in the current turn. At the end of each turn, the Pin markers are removed and the “used” artillery are able to fire again.

I wanted a game flooded with uncertainty, a feeling not always represented in wargames as you usually know how many cards you can use or how many hexagons that unit will move.

Grant: What are you most pleased about with the design?

Ivan: The decisions at the core of the design – one factor units and a 6 ending the turns – were unique and needed much developing and play testing. The units had to behave as their historical counterparts and this caused some trouble for example with the Matildas, the Anti Tank cannons or the measure of support of a fire group.

The developing process has been directed to correct any deviation caused by the use of a single number for movement and fire, and towards the end to balance the game properly.

Having achieved all that, I am very pleased to see the mechanics running smoothly and seeing the players experiencing the sensations I was in mind at the beginning of the process.

Grant: What other designs are you working on?

Ivan: I have many designs at various stages of developing but one is ready to be published. It is a sequel to 1714: The Case of the Catalans, using the same mechanics and with the same emphasis on negotiation based on the Napoleonic Wars.

Thanks for the great insight into the design Ivan and for responding to my invitation for this interview. I really am looking forward to playing this one as it looks interesting and seems to have some interesting mechanics.

If you are interested in 12 Hours at Maleme, you can order a copy for 25,00 € ($27.00) from the SNAFU Design website at the following link: https://snafustore.com/en/second-world-war/1511-12-hours-at-maleme.html

-Grant

Thank you for the interview/review. You’ve convinced me to part with my money. Not an easy task.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry to hold you up!

LikeLike

Excellent interview, thanks! I played the game shortly before it was published and I liked it a lot. Ivan and the Snafu team have designed and developed a great game: simple rules, short lenght, innovative mechanics, intense, fun and with high interaction. The art by Nils Johansson is gorgeus!

LikeLiked by 1 person