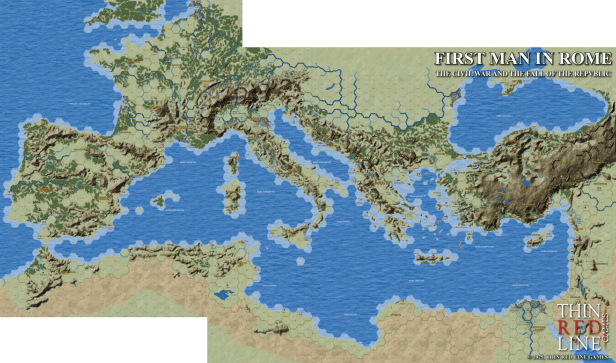

If you are a monster wargame fan then you are probably familiar with Thin Red Line Games and the genius behind the madness Fabrizio Vianello. They are a small but passionate publisher and my favorite thing about them is that Fabrizio speaks in his military jargon so fluently that it is such a thematic boost to the games they produce. Over the past couple of years, we have posted interviews with Fabrizio covering their Cold War Gone Hot games called Die Festung Hamburg and In a Dark Wood as well as the first game in a new Ancients series called The Fate of All: Alexander’s Campaign Against the Persian Empire. Following along in that Strategikon Series is the new volume called First Man in Rome that was just announced. We reached out to Fabrizio and he was of course more than willing to discuss the upcoming release.

Grant: Fabrizio welcome back to the blog. What have you and Thin Red Line Games been up to?

Fabrizio: Hi guys, always happy to be here! It has been a busy year…In July we finally completed the deployment, I mean shipping, of the 4th edition of 1985: Under an Iron Sky, and we are now back to the development of First Man in Rome, the second volume in the Strategikon Series, started two years ago by the Charles Roberts Award winner The Fate of All.

Grant: What historical period does First Man in Rome cover?

Fabrizio: First Man in Rome covers the whole Civil War between Julius Caesar, leading the so-called Populares faction, and the Optimates, initially led by Pompey the Great and then in sequence by Marcus Porcius Cato, Quintus Caecilius Metellus Scipio and Pompey’s sons.

The Civil War lasted from 49 BCE to 45 BCE, ravaged the whole Mediterranean area and beyond, and involved practically every major and minor power of the period.

Grant: What does the tag line “Two is Already Too Many” mean?

Fabrizio: Plutarch tells us that, upon approaching a small village near the Alps, Caesar remarked: “I would rather be first in that little village than second in Rome.”

The old Republican balance of power was crumbling, and seizing the absolute control of the Roman world was now a possibility. The line in the sand had already been crossed by Sulla only a few decades earlier, and even Pompey was not immune to this temptation. In short, the glory and power attainable through the traditional channels of the Res Publica were no longer enough for Rome’s new, ambitious generation of leaders. The time had come for a single man to rule.

Grant: What was your inspiration for this game? Why did you feel drawn to the subject?

Fabrizio: Since I was a kid, ancient history has always been one of my passions, of course together with the Cold War, and I consider Julius Caesar as one of the most relevant figures of the whole of human history. His traces are still very tangible today in the language, in the calendar we use, in literacy, and of course in the art of war.

Grant: What was your design goal with the game?

Fabrizio: As stated in the rules, the main goal is “to give a realistic representation of ancient warfare, without strange salads of godly interventions, auguries, and Homeric duels.”

First Man in Rome forces the players to face the reality of warfare in the represented period. You are not going to simply move your armies around and hope for the best. The final victory will be achieved by the side with better planning, better organization and better logistics.

And never forget money! To paraphrase Cicero, three things are necessary to wage war — money, money, and money.

Grant: What type of research did you do to get the details correct? What one must read source would you recommend?

Fabrizio: The so-called Primary Sources are a must: Caesar’s De Bello Civili, the subsequent works with still disputed authorship but in any case written in the same period (De Bello Alexandrino, De Bello Africo, De Bello Hispaniensi), Plutarch’s Life of Caesar.

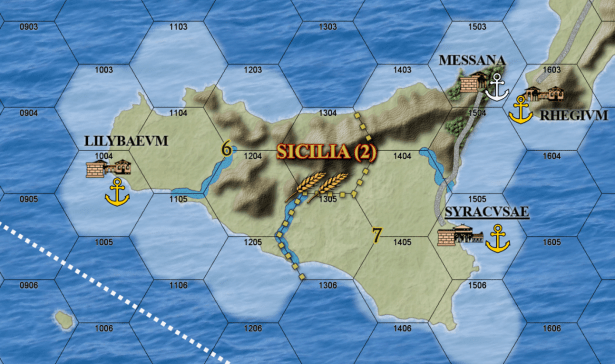

The writing style of ancient historians, Caesar included, is often hard to follow, but there are gems of information hidden in detail. As an example, our doubts about the recruitment capacity in Sicily were cleared by this paragraph in De Bello Civili, Book I Chapter 30:

Cato was in Sicily, repairing the old ships of war, and demanding new ones from the states, and these things he performed with great zeal. He was raising levies of Roman citizens, among the Lucani and Brutii, by his lieutenants, and exacting a certain quota of horse and foot from the states of Sicily.

In just a few words, Caesar tells us that in Sicily triremes could be repaired, legionary troops could be levied, and auxiliary infantry and cavalry could be obtained from the “Free Cities” under Roman control, like for example Syracusae.

A few lines later, Caesar also explains that Cato was not actually able to complete this task, as “when things were nearly completed” Caesarian troops arrived and he fled the island. This tells us that the process of recruiting and obtaining troops from the allies took some time, as Cato probably arrived in Sicily at least one month earlier.

There are also plenty of modern studies covering the period, here’s a few we used:

- The Logistics of the Roman Army at War (264 BC – 235 AD) by Jonathan P. Roth

- Hunger and the Sword, Warfare and Food Supply in the Roman Republican Wars by Paul Erdkamp

- The Roman Cavalry by Jeremiah B. McCall

- Caesar by Adrian Goldsworthy

- Pompey by Giuseppe Antonelli

Grant: What other games have given you inspiration on this project?

Fabrizio: From a gaming point of view, the initial inspiration has been The Conquerors by SPI, covering an earlier period of the Roman history. Please note that it’s only a loose inspiration: the similarities end at the grand operational scale, and the possibility of fighting important battles at tactical level. Some concepts have been inspired by Imperium Romanum II and adapted to the represented period.

Grant: What about ancient combat and particularly during the time of the Roman Civil Wars was most important to model in the game?

Fabrizio: Troop numbers and equipment were of course important, but as in any other historical period a lot of factors made the real difference when it comes to determine the effectiveness of a unit in battle: Experience, doctrine, command structure and morale must all be considered.

Let’s take as example the Macedonian cavalry, the first specifically trained to frontally charge the enemy in wedge formation. This transformed it into a decisive element in battle, despite being equipped practically as any other cavalry of the period.

A lesser-known example concerns the German cavalry, which Caesar consistently describes as superior to both its Roman and Gallic counterparts. Beyond their ferocity—reflected in their high morale—these cavalrymen were supported by light infantry trained to keep pace with the horsemen for short bursts and to strike at enemy mounts. This early form of “combined-arms” tactics was later adopted by Roman imperial forces.

Another important point is the capability of a unit to fight in tight formations, with the rear ranks adding their moral and physical support to the effort of breaking the enemy line. In the Strategikon Series this is represented by the concept of Weight, giving certain units a distinct advantage when fighting in compact, dense formations. Greek Hoplites, Macedonian Phalanx, and Roman Legions all excelled using this approach in battle.

On the command front, the granular command structure of a Legion gave a Roman army a greater flexibility, as even a single cohort was able to react quickly and independently in case of need.

All these elements and more are taken into account in First Man in Rome, no matter if you decide to resolve a battle using the faster “strategic combat”, or to fight it in detail on the tactical map. The composition of your army, the advantage in specific type of troops, the morale, and the leadership will often count more than the simple numbers.

Grant: What is the scale and force structure of units? How has this choice in the design assisted you in telling this story?

Fabrizio: Each unit has a Size, typically going from 1 to 4. For land units, each Size point represents 500 infantry or 200 – 300 horsemen. A typical Roman legion has 5 counters, with each counter representing two cohorts (approximately 1,000 men); A naval unit represents a mix of triremes and transport ships, with each Size point having 10 combat ships.

This scale has been decided during the development of The Fate of All, and it fits well the bigger armies of the late Republican period: Caesar had more than 30 legions at the end of the Civil War, so having 10 counters per Legion would have been a bit too much. 😊

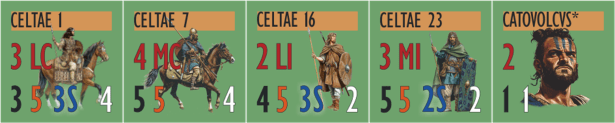

Grant: What is the anatomy of the counters? Can you share several examples of units for comparison?

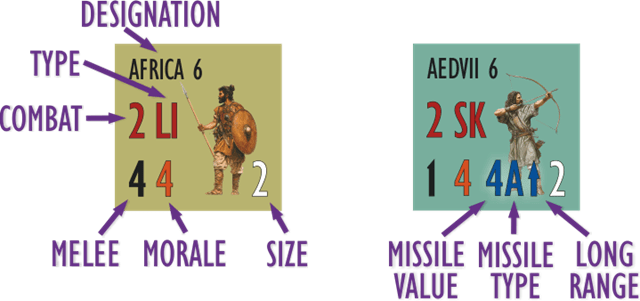

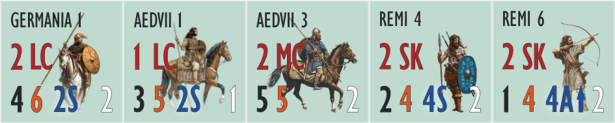

Fabrizio: A land unit has the following information and values:

- Designation: This identifies a specific unit (for example Legio VI Ferrata), or the recruitment area of the unit (for example Gallia Transalpina).

- Type: The type of the unit, influencing several strategic and tactical aspects, and having the following values: SK (Skirmishers), LI (Light Infantry), MI (Medium Infantry), HI (Heavy Infantry), LG (Legionary Infantry), LC (Light Cavalry), MC (Medium Cavalry), RC (Roman Cavalry), HC (Heavy Cavalry), EL (Elephants).

- Combat: The unit’s strength when using the faster Strategic Combat to resolve a battle.

- Melee: The unit’s strength in melee, used when resolving a battle at tactical level.

- Morale: The unit’s morale, defining its capability to resist panic and to recover during a battle at tactical level.

- Size: The size of the unit, with each point representing 500 infantry or 200+ cavalry. This is one of the most important values as it affects several aspects, from logistic to tactical combat.

- Missile Value: The unit’s strength in missile combat, used only during tactical combat.

- Missile Type: The type of missile weapon, influencing the possibility to be out of missiles.

- Long Range: The capability to fire long range volleys, usually limited to archers and slingers.

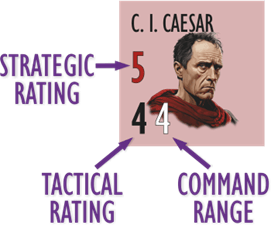

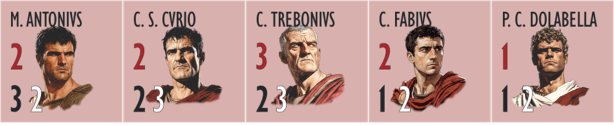

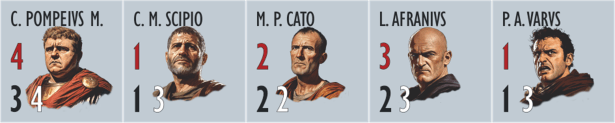

A Leader, one of the most important units as practically nothing happens without him, has the following values:

- Strategic Value: The ability to influence combat, react to enemy moves, conduct forced march, inspire the troops, and minimize losses during a retreat or rout.

- Tactical Rating: The ability to directly lead troops during a melee combat.

- Command Range: The ability to control and give orders to troops during a battle.

Here’s some of the counters of the two factions, minor powers, auxiliaries, and rebels.

Grant: How is Roman Recruitment carried out?

Fabrizio: The recruitment of Roman Legions had a couple of peculiarities, making it different from raising Auxiliary Troops.

First of all, a Legion was always raised from more or less “Romanized” areas, and as a whole: It was ten cohorts, 5,000 men, or nothing.

Second, the Republican Roman army did not normally replace losses within a Legion. Once a Legion was raised, its ranks remained fixed for the entire term of service, which usually lasted several years. By the time of the Civil War, some of Caesar’s veteran Legions had dwindled from their original strength of about 5,000 men to barely 2,000 effectives.

On the other hand, as most Roman legionaries were by the late Republic professional soldiers with no civilian income or skills, it was relatively easy to convince veteran troops to reenlist for another term, usually under the same legionary standard; This gave the Roman army a steady influx of veteran soldiers that could be used as cadre when raising a Legion.

In game terms, recruiting a Legion has the same requisites and limitations described above: Legions can be recruited only from specific areas, losses cannot be replaced, and when disbanded a part of its experience is retained and could be used when recruiting a new Legion.

Grant: How do you model experience in the Legions?

Fabrizio: Each Legion has its own experience level, ranging from 0 (recruits) to 2 (veterans); This experience level is added to the Combat Value, Melee Value, and Morale of all the units in the Legion. As happened historically, a Caesarian Legion of veterans could be able to quickly dispatch a much bigger Pompeian force of green legionaries.

Experience is gained in combat. Each time a consistent part of a Legion is involved in battle, there is a chance to increase its Experience Level.

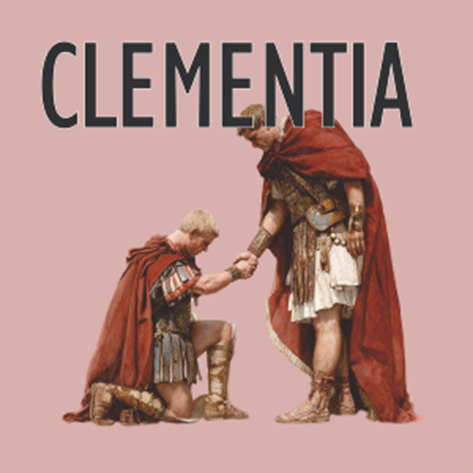

Grant: What rules govern the concept of Clemency (Clementia)?

Fabrizio: The virtue of mercy, leniency, and forgiveness toward defeated foes was a potent weapon in the Roman Civil Wars. Skillfully applied, it could make even the fiercest opponent see that survival was wiser than a hopeless last stand, and sometimes even inspire him to change allegiance. Caesar excelled in this art: His celebrated Clementia won over entire Legions and swayed key political figures, transforming enemies into supporters and turning mercy itself into a tool of conquest.

By contrast, Pompey and the Optimates pursued the opposite course. Since their authority rested on a resolution of the Senate declaring Caesar as an enemy of the state, they were compelled to treat all who supported him as outlaws as well. This rigid stance left little room for mercy and drove many wavering figures into Caesar’s camp, where clemency offered survival and even renewed honor.

In game terms, each Faction has a Clementia Level, determined by its leader’s reputation for mercy or ruthlessness. After every battle, a portion of the defeated Roman troops are assumed to have surrendered rather than been killed outright. The victorious player must then decide their fate:

- Clemency Denied: The captured troops and leaders are executed, and the victor’s Clementia Level may decrease.

- Clemency Granted: The lives of the prisoners are spared. The captured Size Points are then added to a shared Recruitment Pool, representing pardoned or disbanded troops who might later rejoin either army at reduced cost.

And here is the trick: A Faction with high Clementia could successfully persuade most of these pardoned troops and leaders to join (or re-join) its cause. A Faction with low Clementia, however, will find that few — if any — choose to switch faction or serve again under it. In practical terms, this means that showing mercy can be strategically rewarding for a merciful leader, while a ruthless one gains little from restraint: Annihilating its enemies could be a better choice, as it cuts short the possibility they will join the enemy later.

Finally, note that Clementia can never increase; Once lost, mercy’s reputation cannot be rebuilt. It can only decline through executions and acts of brutality: Sacking, Plundering, and Scorched Earth in Roman territories all reduce a Faction’s Clementia Level.

Grant: How does siege work? How have you modeled Roman Circumvallum and Contravallum tactics?

Fabrizio: As you know, the most famous example of Circumvallum and Contravallum is during the battle of Alesia, but the same strategy was used in several other less-known sieges. A Circumvallum will give a besieger an advantage if the besieged army attempts a sortie, while a Contravallum will help against an enemy relief force.

An army may declare it is laying siege to a walled city during a specific phase of the turn. Once Siege has begun, the besieger may also attempt to build a Circumvallum and after that a Contravallum if there is Forest terrain within one hex from the city, and the army contains enough legionary troops. The Strategic Value of the army leader and the size of the besieged city are also taken into account to determine if a Vallum has been successfully built.

Grant: How are Roman Client States handled in the African and eastern regions?

Fabrizio: Ah, the Roman Client States! An endless source of deceit and trickery!

Each Client State has an Alignment: A Neutral client will consider both Factions as “friends”, but its forces will not actively participate to the conflict. Once a Client joins a Faction, its forces are added to that side and the opposing Faction is considered an enemy.

Several things may change the Alignment of a Client: Bribes, the demand of a Tribute, having one of its cities attacked, sacked, or plundered, and some Event Cards. Also note that once a Client aligns with a Faction, it cannot revert to a Neutral status anymore, but it could switch Factions.

Grant: What is the concept of Free Cities?

Fabrizio: Several cities within the Roman provinces held the status of Civitas Libera et Foederata (“Free and Allied City”). Such communities typically paid no fixed tribute and enjoyed a measure of internal autonomy, provided they granted free passage to Roman troops and obeyed directives from Rome. A notable example was Massilia (modern Marseille in southern France), which, despite lying within Caesar’s provincial command, chose to side with Pompey during the Civil War.

In game terms, Free Cities follow rules similar to those governing Client States. They may likewise be required to provide money and troops to their aligned Faction.

Grant: How are Revolts, barbarian incursions and attacks from enemy powers handled?

Fabrizio: Several Event Cards may trigger a Revolt in a controlled province, a barbarian raid, or an offensive from an enemy minor power. The spark is usually a low number of troops in the region, thus forcing both factions to keep consistent garrisons or face possible problems. Once a Revolt or invasion starts, its forces are controlled by a Faction determined by specific rules, different for each event.

Historically, the invasion of Asia Minor by Pharnaces II and the civil war in Egypt happened during the Civil War. Several other things could have happened and are covered: A second Gallic revolt, a raid from Germanic tribes, a Parthian invasion, and a major incursion from the still uncontrolled Gallaecian tribes in Spain.

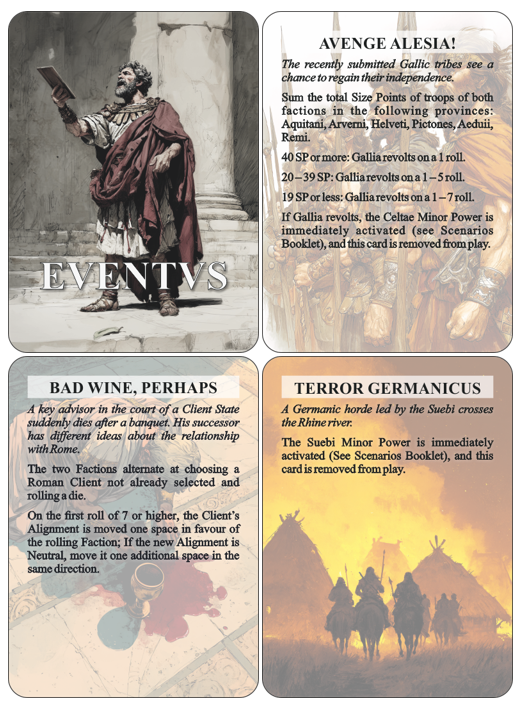

Grant: What role do cards play in the design?

Fabrizio: As usual, cards bring in chaos, natural events, and military or political events that historically happened or could have happened. Each turn has a high chance of having an Event Card drawn, and some of them could cause really big problems. Event Cards are particularly important to reproduce some of the most extreme events that happened during the Civil War, for example the surrender of the Pompeian forces in Spain almost without fighting.

Grant: Can you show us a few examples of these cards and explain their effects?

Fabrizio: Sure! Here are a few sample cards, and a bit of extra explanation about them.

Avenge Alesia: This card may trigger a Revolt in the recently conquered Gallia. The Gallic tribes were mostly subdued by the start of the Civil War, but they were far from having accepted the Roman domination, as stated by the fact that Caesar always left a garrison of at least three Legions plus Auxiliary Troops. If given a solid chance, some Gallic tribes could have revolted again.

Bad Wine, Perhaps: This card may change the alignment of a random Roman Client State. The Roman Clients often switched side during the Civil War, for internal reasons or because they wanted to join the winner’s side. Egypt is a good example: Internally unstable, it initially sided with Pompey, then killed him in an attempt to please Caesar, and finally attacked Caesar when he meddled with the ongoing Egyptian Civil War. Talk about reliability.

Terror Germanicus: When this card is drawn, the forces of the Suebi are placed on the map, east of the river Rhine. Raiding Gallia was a sort of summer sport for the Germanic tribes, in most cases aimed at plundering and not conquering — meaning that these raids left a path of destruction behind them.

Grant: How is combat handled?

Fabrizio: Combat can be resolved with two different methods, at players’ will.

The “simplified” Land Combat maintains a high degree of realism and allows players to determine the result of a battle rather quickly. The battle is resolved in rounds, with each side determining the losses inflicted on the enemy. The composition of each army, the terrain, and the leadership all play an important role. A new round is fought until one of the armies successfully retreats or is routed. At that point, Pursuit and the retreat itself may cause additional heavy losses.

The Tactical Combat is strongly suggested for a decisive engagement; When using it, a full-scale battle takes place. Both armies deploy on the separate tactical map, and fight using every tool at their disposal: Line orders, double encirclement, skirmishers, archers, cavalry charges, melee, morale of each formation, rout, elephants…you name it. The Tactical Combat is inspired by the Great Battles of History Series, even though in my opinion the rules are simpler and more streamlined.

Grant: How is victory achieved?

Fabrizio: Practically every Roman Civil War ended the same way — by eliminating the key leaders of the opposing faction. There was therefore no need to invent new victory conditions: history itself provides the model.

For Caesar and the Populares, achieving such a victory proved complex: New enemy leaders kept rising to replace the fallen, forcing Caesar to pursue his enemies to every corner of the Roman world. The task is much simpler for the Optimates, as Caius Iulius Caesar did not have an obvious replacement, and his death would have most probably caused the Populares faction to fragment or dissolve.

Grant: How many different scenarios are included?

Fabrizio: First Man in Rome includes a total of five scenarios:

Alea Iacta Est: The initial campaign in Italy (49 BCE). A short scenario where time is of the essence.

Fortuna et Celeritas: The first campaign in Spain (49 BCE), with the additional problem of Massilia.

Dies Irae: The decisive clash in Greece between Caesar and Pompey (48 BCE).

Virtus Supra Fortunam: The last stand of Cato and Scipio in Africa (46 BCE).

De Bello Civili: The whole Civil War, from 49 to 45 BCE.

Grant: Who is the artist? How did their work help to realize your vision for the game?

Fabrizio: Thin Red Line Games is, for all intents and purposes, a one-man band — and our modest budget has never allowed for the extensive use of professional graphic artists. As a result, almost everything — maps, counters, document layouts, tables — is created by me, either from scratch or starting from a base design generated by an AI program. It’s a part of every project that demands a lot of time (a single map can take up to two months to complete), but it’s also something I truly enjoy. I’ve had a passion for maps ever since I was five years old! 😊

Grant: What is the next game in the Strategikon Series?

Fabrizio: Good question! The civil war between the Caesarians and the Liberators, the final clash between Octavian vs. Mark Antony, the incredibly chaotic Mithridatic Wars…..Ancient history never runs out of subjects!

Grant: What other games are you working on Fabrizio?

Fabrizio: After the conclusion of this campaign, we’ll probably start working on the 2nd Edition of The Dogs of War; Immediately after that, the last module of the C3 Series: Bavarian Rhapsody!

Thank you so much for your time in answering our questions Fabrizio. I know that you are a busy man, in not only designing games but also in playtesting, creating the art, producing, packing and paying the bills to keep the lights on! I am very much interested in this game and always love a good game on the Roman Empire!

If you are interested in First Man in Rome – Strategikon Book II: The Civil War and the Fall of the Republic, you are encouraged by the designer to reserve a copy immediately by writing a votive tablet (email) to info@TRLGames.com! Don’t miss your chance to join the Legions and defend the Res Publica!

-Grant

Looks intriguing! I also love the ancients, and the Late Roman Republic is my favorite part of it.

Is there any indication how long a scenario (or the full campaign) would take?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not at this point. I think that those types of matters are still in design but we should learn more in the next few months.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Each of the four short scenarios can be completed in a few hours if you are already confident with the rules.

The campaign, well, it takes time….It’s 5 years of total war across the Mediterranean, with a LOT of possible twists 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

More time to move legions around is a good thing 🙂

Thanks for the reply, and all the best for further development!

LikeLiked by 1 person