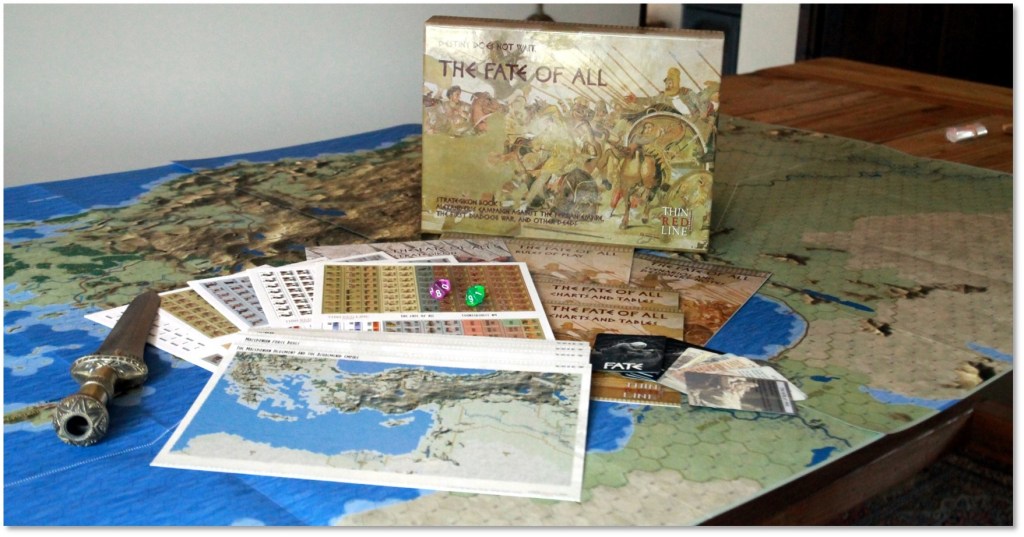

If you are a monster wargame fan then you are probably familiar with Thin Red Line Games and the genius behind the madness Fabrizio Vianello. They are a small but passionate publisher and my favorite thing about them is that Fabrizio speaks in his military jargon so fluently that it is such a thematic boost to the games they produce. Last year, we posted an interview covering their most recent Cold War Gone Hot game called Die Festung Hamburg and now they have a new Ancients game that was put up on pre-order last June called The Fate of All: Alexander’s Campaign Against the Persian Empire. We reached out to Fabrizio and he was of course more than willing to discuss the upcoming release.

Grant: What historical period does your upcoming game The Fate of All cover?

Fabrizio: The period covered by The Fate of All starts in 336 BCE, a few months before the assassination of Alexander’s father Philip of Macedon, and ends in 319 BCE, four years after the death of Alexander.

Grant: What was your inspiration for this game? Why did you feel drawn to the subject?

Fabrizio: Classical Antiquity has always been my other great passion, rivalling my interest for the Cold War, and I think that the campaign of Alexander is the most epic military feat ever accomplished: The distances covered, his military genius, and also his unstable and unpredictable temper are the stuff of legends.

Grant: What was your design goal with the game?

Fabrizio: The first and foremost goal was to give a realistic representation of ancient warfare. More

often than not, the games covering this subject have a simplified area movement, basic supply rules not pinpointing the real logistical problems of the era, or a strategic scale leaving out important details. In the end, some of the historical decisions are forced by the rules or remain incomprehensible, because the reason for those decisions is not correctly represented.

Grant: What type of research did you do to get the details correct? What one must read source

would you recommend?

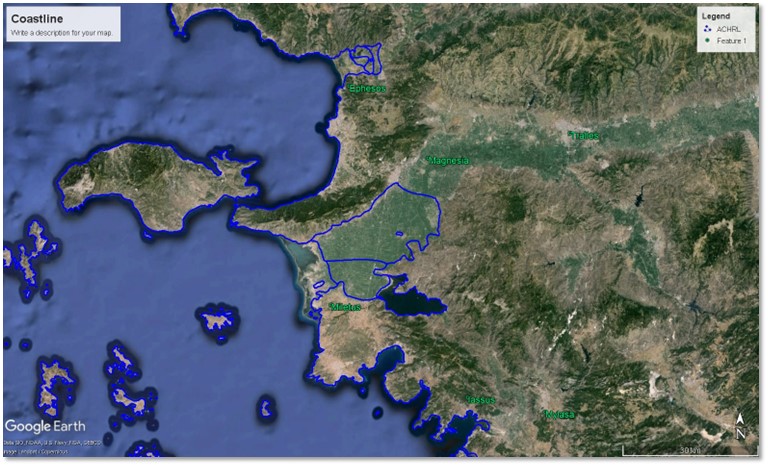

Fabrizio: When we started to deep dive into the events of Alexander’s reign, I quickly discovered that I had vastly overestimated my knowledge of the period. The research covered every possible

field: the changes in the layout of the coastline, the fertility of the different regions, the existence and size of the cities, the pounds of food and forage consumed daily by an army, the equipment and composition of the armies, and a lot more.

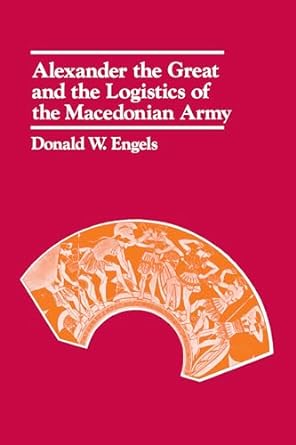

I think there are at least two pivotal studies on the subject: Conquest and Empire by A. B. Bosworth, and Alexander the Great and the Logistics of the Macedonian Army by Donald W. Engels. Engels in particular was a revelation, as after reading it, everything suddenly made a lot of sense to me. Aside from that, all the classical sources and several modern military-focused studies are being used during development. In particular, The Anabasis of Alexander by Arrianhas been chosen as the main and most reliable classical source for two reasons: Arrian based most of his writing on the now lost Ptolemy’s account of the campaign, and he was himself a military commander, thus having a better understanding of the problems and key facts of a military campaign.

Grant: What other published games have given you inspiration on this project?

Fabrizio: The initial idea came from The Conquerors by Richard Berg, and also from Imperium Romanum by Al Nofi. I’ve played and loved both, and they are still among the few simulations with an operational approach to ancient warfare.

Grant: What about ancient combat and particularly during the time of Alexander the Great most

important to model in the game?

Fabrizio: As you may expect, morale, leadership, terrain and fatigue all have an impact on combat

capabilities. The superiority in a specific troop type is also important: A significant numerical advantage in heavy infantry, heavy cavalry, cavalry in general, or missile troops can be decisive during a battle.

Hoplites, phalanx and heavy cavalry were also trained to fight in compact formation, using

the depth of their formation to add mass and kinetic impact in combat. This is a key aspect of

melee combat, often giving the Macedonians a considerable advantage.

Grant: What is the scale and force structure of units? How has this choice in the design assisted

you in telling this story?

Fabrizio: A land unit typically represents 500 to 1,500 infantrymen or 200 to 1,000 horsemen, depending by its Size. The Macedonian army has smaller units, allowing to concentrate them on a critical point, or to cover a wider front at the expense of troop density. For example, the Royal Companions are often used in a packed formation, with up to four squadrons charging and fighting

together at the decision point.

According to most studies, the Persians had a more rigid approach, with a basic tactical formation of 1,000 men no matter if infantry or cavalry. A naval unit represents from 10 to 20 triremes or quinquiremes, plus an undefined number of support and transport ships.

Grant: What is the anatomy of the counters? Can you share several examples of units for

comparison?

Fabrizio: Each land unit may have the following values:

Type: The generic type of unit represented on the counter, such as Heavy Infantry (HI), Phalanx (PH), or Light Cavalry (LC).

Size: An indication of the number of men and horses contained in the unit, determining both its supply needs and its “weight” during combat.

Combat Value: The strength of the unit in a Siege, and in battle when using the simplified

Land Combat.

Melee Value: The strength of the unit in Melee when using Tactical Combat.

Morale: The resistance of the unit to losses, fear and fatigue before giving up and routing from the field.

Missile Value: The strength of the unit’s missile volley.

Missile Type: The type of missile weapons used by the unit including things like Arrows, Bullets or Javelins.

Long Range: The possibility of the unit’s ability to fire a long range volley.

Origin: The background colour indicates the geographic area where the unit can be recruited.

A Naval unit is simpler, as it only uses Type, Size and Combat Value.

Here are some sample units from Alexander’s army (top row) and from the Persian hordes

(bottom row).

Grant: The game has 4 maps. What areas of the ancient world do they cover?

Fabrizio: The map covers the area where the first five years of Alexander’s campaign took place, from Greece to Babylon, and from the Balkans to Egypt. The inclusion of Greece is particularly

important, as it allows an aggressive Persian to threaten the very foundations of Macedonian power. Also, Sparta and the Thracian tribes could be a source of additional problems for Alexander.

Grant: How did you go about out centering the rules to focus on the problems of army organization, supply and morale?

Fabrizio: We wanted to recreate not only the strategic problems, but also the limitations and

constraints that Alexander and Darius faced constantly during the campaign. For example, a big army is slow, and must be organised in different columns to march at the required pace, with every column needing a detachment of light cavalry for foraging. Supply can be problematic for both sides: The huge Persian armies may require an insane amount of food and forage, while the Macedonians have initially significant money problems and cannot afford to waste their gold in supply. Morale has an impact on almost every activity and event, more on this later.

Grant: What role do Leaders play in this process?

Fabrizio: Leaders are a key asset, as nothing can voluntarily move without a commander. Also, a

leaderless army cannot retreat before or during combat, but it can (and probably will) rout. Leaders also strengthen the determination of an army in battle, by increasing the losses that can be sustained before routing. They also have an effect during combat, during a siege and when assaulting or defending a city. Last but not least, both sides have a Faction Leader (the King), whose death could have serious repercussions on morale and on the stability of the controlled territories.

Grant: How do players go about foraging, raiding and reconnaissance?

Fabrizio: Foraging, Raiding and Reconnaissance are all handled by Light Cavalry, a key component of

the army. The total Size of the Light Cavalry available is normally assigned to Foraging, but when the enemy is near, things get more complicated: Both sides may also assign their Light Cavalry to Raiding and Reconnaissance, suffering and inflicting losses during these activities. The Persians normally have an advantage on this, thanks to the sheer quantity of light cavalry they can field.

Grant: How is Supply handled?

Fabrizio: Supply can be obtained in several different ways: Foraging in the countryside, Requisitions from friendly cities, Sea Shipping to a friendly port city, or Plunder. It can also be transported on a fleet, stored in a depot in a friendly city, or carried by a baggage train attached to the army.

Despite the apparent abundance of possibilities, keeping a big army assembled in a single spot is a problem, as Foraging will quickly deplete the local resources, even in a fertile region. As all the other methods require the expenditure of money, the maintenance costs will rise, and when there is no nearby port even money could be not enough to avoid attrition.

Grant: What is the process of dealing with Morale? What positive and negative effects with Morale

are modeled?

Fabrizio: Each Faction has its own Morale that can be changed by military or political events: land battles, conquest or loss of a satrapy, insufficient food, and the death of the Faction leader

are some examples. The King may also decide to donate to the troops in order to increase morale, but this method becomes less effective the more often is used. A particularly low or high Morale affects several things: The possibility for a city to surrender to the enemy, the will to withstand a siege or an assault to the walls, the effectiveness of an army in land combat, and also the losses incurred by an army during a retreat or a rout.

Grant: How do you incorporate Political aspects into game play?

Fabrizio: Most provinces have an Alignment, representing the stance of the local governor and the

ruling class toward the warring Factions. The alignment of a province can be altered by the actions of a Faction within its territory: When an army plunders or sacks a city, or implements a Scorched Earth policy, the alignment of the impacted province will shift towards the opposing side. Military events also have an effect: When a satrapy is conquered, its alignment is shifted toward the conquering Faction, as the Satrap and any strongly hostile element is “removed” by the conqueror.

The Persian gold can also be used to convince regions not firmly under Macedonian control to revolt, as in the case of Sparta and Thrace. Alexander cannot consider his backyard secure and must always keep a credible army and leader in Greece. Historically, this was the role of Antipater.

In the end, the Alignment of a province will influence the taxes raised, the determination of the defenders during a siege, and the possibility of revolts and surrendering.

Grant: What role do cards play in the design?

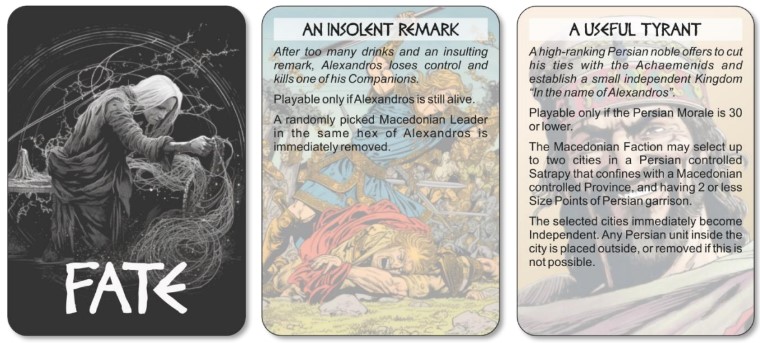

Fabrizio: The Fate Cards are all based on historical facts or events that cannot be controlled.

Conspiracies, treasons, natural disasters, and spies are all in the deck. In a couple of cases, they also show the darker side of Alexander’s personality, his Daemon as the Greeks called it.

Grant: Can you show us a few examples of these cards and explain their effects?

Fabrizio: Sure! Here’s two of my favourites.

An Insolent Remark is inspired by the murder of Cleitus the Black by Alexander, after an argument between the two went out of control during a drinking party. Alexander simply killed Cleitus on the spot, using a javelin taken from one of his bodyguards. The event removes a random Macedonian leader in the same hex of Alexander, and also decreases the Macedonian morale by two.

A Useful Tyrant is inspired to Dyonisius of Heraclea, and other nobles who formally submitted to Alexander and were granted a certain degree of independence over their territory.

Dyonisius was particularly well versed in surviving, and was able to maintain its position as Tyrant of Heraclea under Darius, Alexander, Perdiccas and Antigonus, simply by switching side at the right moment. The event makes a couple of Persian controlled cities independent, expelling any on-site

Persian garrison.

Grant: How is combat handled?

Fabrizio: The “simplified” Land Combat maintains a high degree of realism, and allows players to determine the result of a battle rather quickly. The battle is resolved in rounds, with each side

determining the losses inflicted on the enemy. As I said earlier, the composition of each army, the terrain, and the leadership all play an important role. A new round is fought until one of the armies successfully retreats or is routed. At that point, Pursuit and the retreat itself may cause additional heavy losses.

Grant: What are the main differences between Strategic and Tactical Combat?

Fabrizio: The two are completely different, and Tactical Combat is strongly suggested for a decisive

clash. When using Tactical Combat, a full-scale battle takes place. Each army deploys on the battlefield, and fight using every tool at its disposal: Oblique order, Cannae-style double encirclement, archers, cavalry charges, the wall of the phalanx, morale of each contingent, melee, rout, elephants, chariots….you name it.

Tactical Combat is inspired by the Great Battles of History Series, even though in my opinion the rules are simpler and more streamlined.

Grant: How do Satrapies, Taxation and Bribes work? Why were these important to include?

Fabrizio: Each province has a basic tax value, but the exact amount of taxes collected each year will also depend upon its alignment and by the presence of cities still under enemy control. The main source for the Persian tax values has been a report by Herodotus, listing the tribute in talents for each satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire. Of course, the Persians can raise a huge amount of money, most of them coming from the far east satrapies. Bribes could play a decisive role. A successful Bribe changes the Alignment of a province, influencing taxation, and making revolts and surrendering more or less probable. Bribery can be used both on friendly and enemy controlled provinces, and it is a particularly useful tool for the Persians as they have plenty of gold to use.

Bribing an enemy controlled province could also backfire if the treason is discovered and the corrupted functionaries are removed or executed. Alexander showed particular attentiveness to this type of news.

Grant: How is victory achieved?

Fabrizio: In the campaign, it’s all or nothing. The Macedonians must conquer at least 15 satrapies, bring the Persian Morale to a critical level, and control the power centers of the Achaemenid Empire. Killing Darius could also facilitate victory.

The Persians must keep control of their satrapies, bring the Macedonian Morale to a critical

level, and undermine the Macedonian hegemony in Greece. In their case too, killing Alexander early could deliver the decisive blow.

Grant: How many different scenarios are included?

Fabrizio: The Fate of All includes five scenarios.

The Anger of Achilles: The first five years of Alexander’s campaign (334 – 330 BC)

Ten Thousand, Again: The preparatory expedition of Parmenion into Asia Minor (336 – 335

BC)

Arise, Hellas!: The Greek revolt following Alexander’s death (323 – 322 BC)

The Shattered Bonds: The first Diadochi War (320 – 319 BC)

It All Comes to This: The decisive clash between Alexander and Darius (331 BC)

Grant: Who is the artist? How did the art help to realize your vision for the game?

Fabrizio: Our small budget never allowed the use of graphic artists, except a couple of times for the

box art, but this project required additional help. Jose Ramon Faura realized the art for most of the counters, I’ve been impressed by his ability to define the characteristics of an ancient soldier using only a few colours and strokes. Everything else has been made as usual by me, starting from scratch or from a base drawing created by an AI program.

Grant: What is the next game in the series?

Fabrizio: I think that Caesar and Pompey are eagerly awaiting their turn, not to mention the possible

expansions involving Alexander including Xerxes, Leonidas, and the Diadochi.

Grant: What other games are you working on Fabrizio?

Fabrizio: With The Fate of All now concluded, we are ready to begin the fourth module of the C3 Series, titled In a Dark Wood and covering the Warsaw Pact offensive in the Hof Gap sector.

Thank you so much for your time in answering our questions Fabrizio. I know that you have been busy not only designing the game but in getting it produced and packed so you can ship those off soon to the many interested wargamers.

If you are interested in The Fate of All: Alexander’s Campaign Against the Persian Empire, you are encouraged by the designer to reserve a copy immediately by writing a Votive Tablet (email) to info@TRLGames.com! You can also find more about the game at the following link: https://trlgames.com/the-fate-of-all/

-Grant