I am always very interested in games that are designed by veterans as they bring a very real experience and viewpoint on the subjects they are trying to tackle. What’s that old saying…“straight from the horse’s mouth”. And this one is a simple deck building (or they use the term construction) game that is sure to be one of those fast playing affairs that can be used as night cap for game night.

My only true concern with the project is the use of AI art. I am not as against it as others in our space but I do prefer real art as it can add so much to a game and give it a really thematic integration for us as players. I understand the use of the technology but am not as sold on it as others are. But this is not my game and not my say.

If you are interested in #Maneuver Warfare, you can order a copy for $30.00 from The Dietz Foundation website at the following link: https://dietzfoundation.org/product/maneuver-warfare/

Grant: Ian welcome to our blog. First off please tell us a little about yourself. What are your hobbies? What’s your day job?

Ian: I’m fortunate in that my day job—at least more days than not—also lines up with my hobbies. I’m a retired Marine Corps helicopter pilot, and thanks to some stars aligning I spent my final years in uniform as the operations officer at the Brute Krulak Center for Innovation and Future Warfare at Marine Corps University in Quantico, Virginia. Part of my duties at the Krulak Center was using various wargames as tools to support the professional military education (PME) curricula across the various schools of Marine Corps University. I retired in 2023 and jumped to my current day job, which is as a wargame analyst for Group W, a Systems Planning and Analysis (SPA) company. We do work on many different contracts for the Defense Department and other national security organizations, and that includes frequent analytical wargame events.

As to my hobbies—first and foremost, I love playing games with my kids. They’re not always interested in the same types of games that I used to run for PME, but sometimes there’s overlap, such as when I used several different variants of the Commands & Colors Series to help teach my eldest son American military history from the American Revolution through World War II. I’m a huge Star Wars fan, and so I’ve also jumped into the pool of Star Wars games—X-Wing, Armada, Legion, Rebellion, Mandalorian Adventures, and the recently released Battle of Hoth—for, you know, the kids. I also like facilitating wargames for others to get them into the genre, and I regularly run games at Origins, Connections, Circle DC, and the Armchair Dragoons Fall Assembly.

Other hobbies include writing—I’ve written two books on John Boyd and maneuver warfare, topics which heavily influenced design decisions for the #Maneuver Warfare card game, as well as professional articles, short stories, and a graphic novel script that explore military history, military theory, and aspects of future conflict. I periodically co-host a podcast for War on the Rocks. Besides #Maneuver Warfare, I’ve done play-testing and design work for the Littoral Commander series of games, and have a couple of other prototype game designs on the back burner. And during the fall, every Sunday I wait for the New England Patriots to break my heart yet again, though I know that after two decades of great times no one feels sorry for us.

Grant: What motivated you to break into game design? What have you enjoyed most about the experience thus far?

Ian: A big part of the answer is tied to my former work at the Krulak Center. I came to the Krulak Center in 2019, just before the then-Commandant of the Marine Corps General David Berger released his Planning Guidance which heavily emphasized wargaming as, among other things, a valuable PME tool. From our perspective it was great that our Center’s activities had just gotten top-down endorsement, so we started looking at game options to put in front of our PME students. The problem was that commercial wargames don’t always meet the necessary criteria for PME. PME curricula always have a time constraint, and instructors aren’t looking for subject matter that falls outside the learning objectives of the course. So the wargames we offered had to be accessible and relevant. And as our Center looked for options that were accessible and relevant, it turned out that there were not many choices when it came to games that focused on current and future conflicts, which could be taught and run in a few hours, and which captured the problems across all domains that PME learning objectives gave to their students. There are hundreds of choices when it comes to re-fighting the Eastern Front at the operational level in World War II. There were far fewer choices when it came to things like a Marine Expeditionary Unit conducting humanitarian aid/disaster relief, or a Marine Littoral Regiment facing off against Peoples’ Liberation Army (PLA) forces in the South China Sea.

Some fortunate timing helped solve that problem, as well as offer me the chance to start dabbling in game design. In 2020 during the COVID pandemic, one of the members of the Krulak Center’s Non-Resident Fellow community, Sebastian Bae, said that he had a team of graduate students working on a wargame prototype as a COVID project. This prototype game focused on Marine Littoral Regiment tactical operations in the future against PLA forces in the Indo-Pacific region. Sebastian asked if I thought this game might be useful for our PME students; my answer was a resounding “YES,” because this game was both obviously relevant given its subject matter, and accessible because it was being designed as an introductory wargame intended to be played in a few hours.

The full story of how I leveraged this game—which would go on to become the Littoral Commander commercial tabletop game—for PME is beyond the scope of this interview. Suffice it to say that it became my “go to” wargame for Marine Corps students. And as it became more integrated into PME courses as a teaching tool, I started getting requests from both students and faculty to design new scenarios, new mechanics, and new orders of battle that were not in the core game. This is really where my game design journey started, by first experimenting with how to push the boundaries of the Littoral Commander game engine to its limits. Once I got comfortable enough pushing, tinkering with, and rewriting the core game engine through numerous additional scenarios, geographic locations, and then real-time prototyping of what was almost an entirely new game following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, I started thinking to myself: what if I tried making a Marine Corps-focused game that was also accessible and relevant, but with a different form-factor and teaching objectives?

This thought led me all the way back to my pre-Marine Corps life, when among the many games I played was the Star Wars Customizable Card Game from Decipher (popular in the mid-1990s). And then I wondered how a game in that style might be used to help teach Marines both more about their own doctrine—a separate topic where I’d devoted a large amount of professional writing—and current and emerging trends in multi-domain warfare. That’s where the idea for #Maneuver Warfare: The Card Game took shape.

Grant: What lessons have you learned from designing wargames?

Ian: Oh, so many lessons! But a few stand out. First, there is no substitute for lots of play-testing, and ensuring you play-test with many different audiences. I hoped my game would be played primarily, though certainly not exclusively, by U.S. servicemembers, especially Marines, so I sought play-testing opportunities with that demographic to see how well my game design matched the military problems they might have to face. But not all Marines are gamers, and so I also looked for events where I could get input from gamers who might not necessarily have any military background. Finally, I was fortunate to have access to a few wargame designers and PME instructors who used wargames for their own courses.

All of these play-testers were vital to the process. The servicemembers could tell me if I was effectively capturing the different challenges of multi-domain operations I wanted my game to cover. The non-military gamers helped me refine game mechanics, the design and “feel” of the cards, balancing complexity with richness of what decisions players made. The wargame designers and PME instructors had actually designed games and used them as teaching tools, and so provided insights from their experiences to solve deeper design questions and ensure that the game was actually teaching the lessons I hoped it would teach.

Second, there is no room for ego in a good design process. I spent more than two years doing play-testing, from one-on-one sessions with people I’d invited to play-test to civilian play-testing groups like “Break My Game” to professional organizations like Connections to big game fairs like Origins. I got a lot of feedback from these events, and it wasn’t always things I liked to hear. I figured I had a pretty thick skin since I already had a paper trail as an author, and every article or book I’d written had gone through some kind of editorial process where I would sometimes have different opinions than the editor on whether a change was really necessary. But play-testing was like having dozens of editors, telling you month after month that your game would be much better if only it did X, or you changed Y, or eliminated Z; and then you start your changes over again at A, and cycle through the whole alphabet several times to boot.

#Maneuver Warfare was my baby, my first major game design, and I poured countless hours into making each aspect of the game the best I possibly could. Nobody likes hearing that their baby is ugly, but by keeping my ego in check and accepting criticism as objectively as I could, it made the game much better. Had I reflexively rejected feedback because I thought the critic was too nit-picky, or not from a military background, or lazy because they didn’t want to read all the words on my cards, I would have missed many opportunities to actually move the game closer to my own vision for it.

This included a very late-breaking change that came exactly two years in the play-testing process during the 2024 Origins game fair. I talked about this experience at length over at Armchair Dragoons, but here’s the short version. In 2024, I had The Dietz Foundation lined up as a publisher for #Maneuver Warfare, I’d done two years of play-testing at that point, and so in my mind the design was locked in—Origins 2024 would simply be to promote interest in the game before finalizing the design with the publisher. Then came a couple of very experienced wargamers whom I greatly respected, I proudly showed the game off to them…and they said my core mechanics for performing actions and achieving victory conditions needed to be radically restructured. I was stunned. They gave me 5 hours of feedback and I didn’t sleep that night as I mulled it all over in my head. I was terrified that their changes would “break my game,” forcing me back to the beginning of the design process, forcing me to tell my publisher that he might have to wait another six months or a year for a final version. There was a voice in my head tempting me to say “thanks, but no thanks,” because I’d walked into Origins believing my game was finished and couldn’t bear the thought of walking out and starting over.

I’m glad I didn’t listen to that voice, because there was another voice telling my ego to shut up, process the new information, and see whether it would make the game better—you know, just in case I actually cared more about the game than taking the easy way out. After that sleepless night, I came back to Origins the next day with a few new rules to try out in the hope that the 5 hours of feedback could be integrated into the game framework without breaking it. Turned out, the feedback could not only be integrated but created the chance to add a true OODA Loop to gameplay. The absence of an OODA Loop had always bothered me given I was naming the game after maneuver warfare doctrine of which the OODA Loop is an integral component. But despite two years of play-testing, up to that point I hadn’t found an organic way to use the OODA Loop. Thanks to the late-breaking feedback, I had an OODA Loop and it elevated the game flow to more fully achieve the educational aims I wanted the game to fulfill.

Ego would’ve had me ignore eleventh-hour feedback. After all, I’m the designer, not the players; I know when the game is “done,” right? But good feedback is good feedback no matter what point in the design process it pops up. Good writers know to listen to their editors and “kill their darlings” if the editor thinks it will make the piece better. I learned that to be a good game designer, you better get used to killing your darlings and be ready to do so no matter how deep in the design process you are.

Grant: What is your new upcoming game #Maneuver Warfare about?

Ian: #Maneuver Warfare is about two things: turning Marine Corps maneuver warfare doctrine into something tangible, and providing Marines—and hopefully members of other military services, and non-military players—with a simulated environment in which they can explore the problem sets of modern and future warfare.

Grant: Why was this a subject you wanted to focus on?

Ian: Maneuver warfare doctrine was a professional focus area of mine well before I thought about designing a game around it. The Marine Corps adopted maneuver warfare as its capstone warfighting philosophy in 1989 following more than a decade of debate and introspection. Maneuver warfare was intended to be the approach through which the Marine Corps would organize, equip, and train itself in order to contribute to American defense objectives even though it was the smallest and least-funded of the service branches. The story behind how the Corps adopted maneuver warfare—the “why” behind the decision, as opposed to adopting other doctrines like AirLand Battle—is deeply fascinating. But for my generation of Marines, the GWOT generation, that story was largely unknown. We’d be handed a copy of MCDP-1 Warfighting during entry-level training and told to study it, with the implication that its insights were self-evidently valuable and applicable.

And for most Marines…that was it. The term “maneuver warfare” might come up later during formal PME courses with a few page citations from MCDP-1, but the space between those courses was measured in years. During flight training the OODA Loop would be mentioned as part of the decision-making cycle in the cockpit but not explored any more deeply. I was largely ignorant of how the Corps came to maneuver warfare and why its adoption was so radical at the time, until that very story became the focus of graduate work I did starting in 2015. Once I dug into the story, I found it fascinating but was also frustrated that the Corps had done such a poor job telling its own story. That frustration motivated me to write a book to retell that story. The book seemed a sufficient solution to me, for a while; but then as I saw the “aha” moments created by wargaming at Marine Corps University, I thought there might be value in letting Marines actually “play” their doctrine instead of simply reading about it.

The second goal of the game—exploring modern and future warfare—was important to me because following the end of the GWOT era, the U.S. military has, with very isolated exceptions, been a peacetime military. Unfortunately, we don’t live in a peacetime world. The possible future challenge of facing off against a peer adversary in the form of the PLA would expose U.S. servicemembers to a scale of war none of us in uniform had any experience in. And then Russia invaded Ukraine, and gave us a stark picture of what modern combat would look like. Modern war was highly violent and required leaders at even the lowest tactical levels to think beyond the terrestrial domains in front of them. A Ukrainian squad leader doesn’t just fire their rifle on the land domain, but uses drones in the air domain to attack Russians from above, uses space-based Internet via StarLink to communicate with higher headquarters and adjacent units, and sends recorded video from successful drone attacks into the information domain to raise funds or their unit’s military hardware. And despite not having a navy, Ukraine has leveraged drones and long-range precision fires to deny Russia the advantages of a conventional navy on the Black Sea.

There’s not a Marine in uniform today who has experienced war like this. Even that more senior generation of Marine who fought in the GWOT did not experience war like this—their adversaries were deadly, but a Marine in Iraq or Afghanistan never had to worry about fighting to control air, space, or maritime domains. Against a peer adversary like China, we could not assume anything approaching dominance in air, space, sea, or information. So I wanted to create a wargame where military players could experience, in an admittedly abstract and simplified sense, the challenge of having to fight across all domains simultaneously.

Grant: What are the unique features with the system used for the game?

Ian: While I adapted mechanics I’d seen in many other games, I think there are a few things that are unique to #Maneuver Warfare. First, the game has a semi-randomized terrain laydown mechanic that I included to ensure that no two battlefields would ever be the same. Players have some control over where they fight by getting to deliberately select a small number terrestrial domain cards that match their deck strategy. But then there’s a blind draw of additional terrestrial domains, and further randomization by adding a separate layer of cards that capture things like weather, natural disasters, and even space debris—all things that two adversaries might encounter on a battlefield and which can’t simply be wished away. A mantra in the U.S. military is that you don’t always get to pick where and when you’ll fight, but you’re still expected to go forth and win. With two different layers of randomization for the game’s battlefield, players will find that they’ll have to adjust their strategic approach because the “gear” they brought to the fight—their deck of cards—may not work as well in the battlefield they’re forced to fight on.

A second unique feature is that I took the Clausewitzian notion that “war is a clash of wills” and made that the literal victory condition of the game. Each side starts with a repository of “will to fight” that ebbs and flows throughout the game as they inflict or take losses, succeed or fail in the information domain, and care for or ignore the civilian population impacted by their military actions. “Will to fight” will inevitably go down as players take combat losses because no war is bloodless, so a key part of player strategy is thinking about what cards to include to mitigate that loss of will, or regenerate it during the game.

Third, that late-breaking feature of the OODA Loop is something that I don’t think any other wargame has tried to capture the way #Maneuver Warfare does. I made the OODA Loop into the cycle of action each players takes during their turn, with a delay in between when players spend actions and then have those actions come back to them. This is intended to represent the inherent sequencing of the OODA Loop, where you decide what to do, then do it, but then you have to watch the outcome of your action and then analyze what your next set of actions will be based on your previous actions.

But a fundamental part of maneuver warfare doctrine is degrading your opponent’s decision-making cycle—their OODA Loop—while preserving or accelerating your own OODA Loop. And so I included many different ways in which tactical actions on the battlefield have a second-order effect on player OODA Loops. For example, if you destroy an enemy unit, your opponent has to remove that unit from the battlefield and takes a hit on their “will to fight.” But there’s a mental impact as well on a commander to losing a unit unexpectedly; the commander is forced to pause, adjust, reassess, and figure out how to execute their own plan absent expected resources. All of this adjustment slows down the opponent’s OODA Loop because they’re now forced to deal with the unexpected. So when you destroy an enemy unit, not only does the opponent lose “will to fight,” but action cards in their OODA Loop are forced back to an earlier step to reflect sudden limits on their freedom to act. Conversely, you can do other things which “fast forward” actions in your own OODA Loop, expanding your freedom to act.

I don’t think any other game includes such a literal manifestation of a mental decision-making cycle, or how one’s cognitive state can be influenced by battlefield actions.

Grant: What is your design goal with the game?

Ian: In addition to teaching maneuver warfare, and teaching lessons about the modern battlefield, I had a very specific design philosophy for #Maneuver Warfare: make it “expeditionary,” or as I’ve said in some promotional material, “put future war in your cargo pocket.” I wanted this to be a game that Marines could play in the most austere of locations, with the absolute minimum of external support needed. All you need to play the game, in addition to the cards, is a light source and a flat surface.

This was important to me because as much as I love any number of tabletop wargames, most of them—especially the more detailed ones—require a good amount of table space to set up. Moreover, most tabletop games have a fair number of bits and pieces, like a map, unit counters, potentially unit trackers, dice, wooden cubes or blocks. That’s a lot of stuff to lose should someone jostle your table, should your table be rocked back and forth by waves, or if you need to frequently pack and re-pack all your personal belongings to move to a new location. These are all things likely to happen to Marines in austere environments.

So I wanted to make the game as simple and portable as possible. There’s only one component: cards. Throughout the design process I had to make myself cap card counts at manageable numbers. This was so that players could literally carry the entire game in the cargo pocket of a military uniform, and that even when fully laid out, the game would require only a modest amount of table space. And I’ve tested this, to include play-testing the game on the tailgate of my truck.

Grant: What other games did you use as inspiration?

Ian: I was certainly heavily influenced by Littoral Commander, which uses cards as a key part of gameplay, and more importantly, captures the integration of all-domain operations in a way that few other modern wargames do. Other older, classic wargames shaped parts of my design as well—my turn sequence has players deploy units only after all combat operations are complete, similar to Axis & Allies. But the Star Wars Customizable Card Game I mentioned above had perhaps the strongest influence, because when I first toyed with the idea making an “expeditionary” wargame that was also educational, I realized with the benefit of hindsight that the Star Wars game covered a lot of things that I wanted my game to do. Semi-randomized battlefields? Check. Using deck construction to mirror the military challenges of force design and task force specialization? Check. Having a random number generator (i.e. dice) integrated into the game cards? Check. I wound up taking each of these elements in different directions in my own game, but the Star Wars CCG gave me a good foundation for how to build a rich military-focused game with lots of interesting decisions and replayability while only using a single component: cards.

Grant: How does the deck construction element of the game work?

Ian: While deck construction is certainly not a new mechanic, in my game I frame it to the players as a force design/task organization decision that military leaders face every time they’re given a mission. On paper, a battalion commander might have access to a huge amount of support–logistics, aviation transport and fires, cyber, space-based ISR and communications, joint force assets–but for a specific mission you may only be allowed to use a fraction of those assets. For a Marine commander in an expeditionary environment like embarking on a Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU), this problem has an especially hard limit on it: there is a physical space limitation on how much equipment that MEU ships can embark. So even though a battalion commander might have a number of assets like vehicles and fire support that they have direct control over and don’t need to beg or borrow from higher headquarters, MEU ships simply can’t fit it all.

Thus the commander has to do an assessment of their assigned missions, what assets are essential to that mission, what capabilities a potential adversary might bring to bear, and make judgment calls on what assets to take and which ones stay at home. And there’s always the chance that your mission assessment may be wrong, or the adversary has an unexpected capability that you’re not optimized to deal. In those cases, turning around and saying “sorry, I’m not able to fight this fight” is not an option. You go to war with what you have.

That’s what I tried to build in to the deck construction mechanic. The Red and Blue players have roughly 90 cards on their side representing different capabilities across all domains, but they can only build a deck of 30. They have to make judgment calls on what to include and exclude, and once the game starts there’s no calling ”time out” so you can swap out cards that you may have omitted. Players construct their deck based on the same considerations as a military commander: what’s my bid for victory, what do I think my enemy might do, and how do I hedge both against my enemy and unexpected factors like poor weather or terrain for which my assets may not be suited? Players build their decks ahead of time, and have the option to change cards at any point before the terrain set-up phase of the game begins; but once players start building the semi-randomized battlefield, their “task force”–their decks of cards–is locked in, and they’ll have to go to war with the force they have.

Grant: How do players add and remove cards?

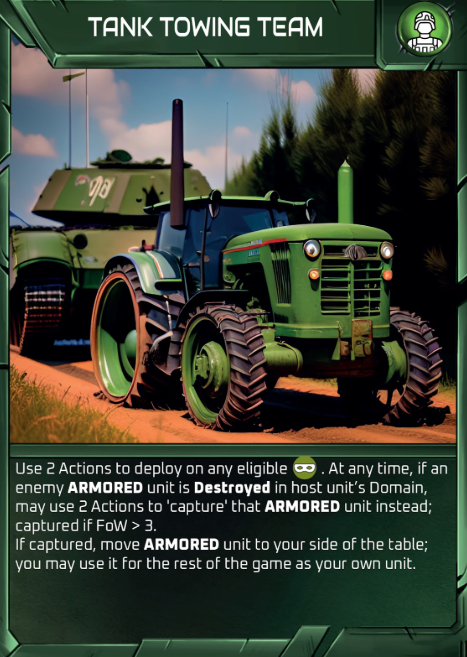

Ian: Once both players have constructed their decks, done the terrain laydown, and started the game, the flow of cards from the deck to the hand to the table (and often, back to the deck), is as follows. I should first start by noting that there are two categories of cards: Action cards and Maneuver cards. Actions cards are the players’ currency for doing virtually everything within the game and I’ll talk more below about how they cycle through the OODA Loop.

The Maneuver cards represent military units, more intangible capabilities, and ways to inject Clausewitzian “friction” into the opponent’s plan. These are the cards players fight each other with. The game’s hand size is seven Maneuver cards, and players start the game having pre-selected their initial seven cards. The remaining Maneuver cards form the Maneuver deck, essentially the player’s task force reserves that will be deployed as the game unfolds. Players spend Action cards to deploy Maneuver cards to the battlefield; once deployed, players use additional Action cards to move the Maneuver cards around, to conduct combat with them, and to play those special “friction” cards outside the normal turn sequence. As Maneuver units get destroyed in combat, they come off the table and go back into the Maneuver deck where they can potentially be redeployed on future turns. I use the military definition of “destroyed” which is to be rendered combat ineffective; so when a Maneuver unit is destroyed and comes off the table, that doesn’t necessarily mean that every human or machine in that unit has been utterly annihilated, but that it’s no longer able to contribute to combat and would have to be reconstituted before it can be used again.

Just as assembling, deploying, and moving forces in the real world isn’t “free” – it costs you gas, money, time, etc. – pulling new Maneuver cards out of your Maneuver deck isn’t free either. EVERYTHING in the game costs at least one Action. So after players deploy units from their hand, on future turns they can refill their hand from the Maneuver deck; but drawing each card costs an Action. Likewise, if the unfolding battlefield situation requires that you discard certain Maneuver cards from your hand to make room for more useful ones, discarding a Maneuver card costs one Action as well. There are certain card capabilities that can reduce the Action cost of doing things, but in general, nothing in the game is free, and players will quickly realize that they have to manage their flow of Action cards to ensure that they can move, fight, and deploy each turn without burning through their resources and thus potentially limiting their future decision-making.

Grant: What type of units are included in the game?

Ian: The two player faction options are Blue and Red – the Blue faction features abstracted versions of U.S. Navy and Marine Corps units, while Red is an amalgamation of Russia and China with some terrorist attributes mixed in as well. I’d say about 70% of Blue and Red units mirror each other, so both sides have “naval” or “maritime” infantry (i.e. Marines. However, for specific legal reasons I could not actually call them Marines, having watched my friend Sebastian Bae go through a lot of heartburn with the Marine Corps Trademark Office over using the term “marine”), special forces, fourth and fifth generation fighter aircraft, cruisers, amphibious ships, submarines, various types of satellites, logistics units, etc.

But that 30% differential makes for interesting asymmetries on each side. Red, for example, has tanks – the U.S. Marine Corps divested its tank companies several years back as part of Force Design 2030 – and hypersonic missiles. Conversely Blue has International Affairs units and Civil Affairs Groups that represent our collaborative soft power as opposed to China and Russia’s strong-arm tactics.

Even in the mirrored units, however, I implemented some differences that reflect the U.S. military’s more qualitative approach to personnel and equipment. Overall, Red units are cheaper to deploy and don’t incur as much of a “will to fight” penalty when destroyed; lives are cheaper for Red than Blue. But Blue’s equivalent units are generally more capable – Blue fighter aircraft, for example, can move a little farther and have better offensive and defensive values than Red’s. Blue units also have higher leadership values to reflect better training, delegation of authority to lower levels, etc.

Should there be sufficient demand for #Maneuver Warfare to justify future expansions, I already have a number of ideas for adding more Army, Air Force, and Space Force capabilities, as well as potentially creating a third faction that is specifically modeled after terrorist/criminal organizations.

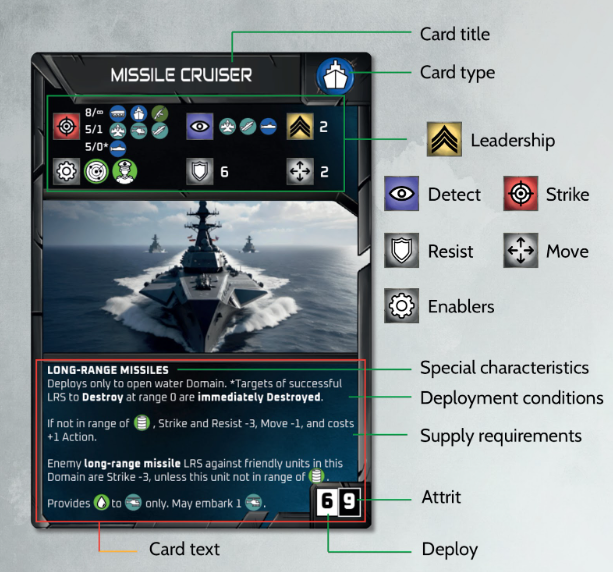

Grant: What is the anatomy of the cards? What different types of cards are included?

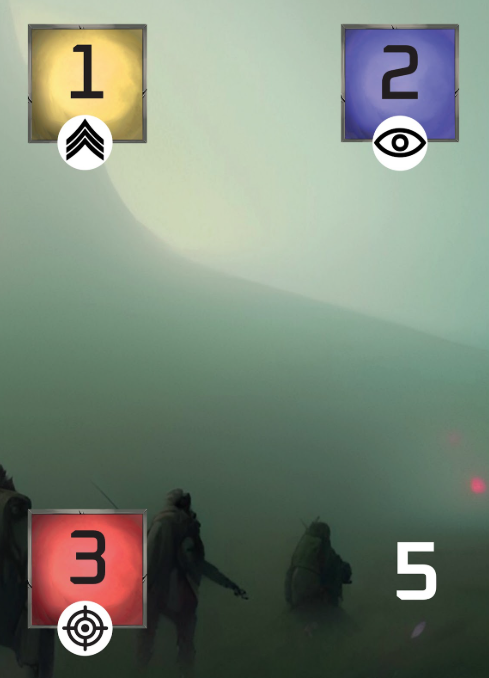

Ian: Here is a graphic that shows the layout of each card.

There are four card categories which I’ve touched on already but will explain in detail here. For the player deck, the two main categories are Action cards and Maneuver cards. There are a total of 30 Action cards in the game, and these function as the game’s currency—just as nothing’s free in life (or war), nothing’s free in the game either. Everything costs at least 1 Action to do (though players have a few modifiers available to reduce costs). Players cycle Action cards through the OODA Loop Cycle to draw or discard cards from their hand, initiate combat, move units, deploy new units, or play “friction” cards to mess with their opponent. Action cards also work as random number generators; in other words, dice.

On the face of each Action card are four number categories that can be used to adjudicate four areas of the game: detecting hidden units, conducting long-range strikes, leadership bonuses, and then a generic number to adjudicate any other player action. They’re based on D6 values, and the numbers in the four categories are randomly distributed so that a card with a high Leadership value may have a low Detection value. I did this partly to add a “fog of war” element to these adjudications, and partly as a subordinate element of deck construction strategy. Player decks are a total of 60 cards, and that means a player can have up to 30 Action cards and 30 Maneuver cards; or they can opt to reduce the number of Action cards in order to add more Maneuver cards. Players can make a risk decision that, for example, having 5 fewer Action cards is worth it to have 2 more naval units and 3 more aircraft in the Maneuver deck. In this case, the player still gets to select which Action cards they use—so if they have a firepower-heavy strategy, they’d want their 25 remaining Action cards to have higher numbers in the Strike category to improve the chances of successful long-range strikes. However because of the random number distribution, that player is then also accepting greater randomness in all other number categories. Is that a smart risk or foolish risk? It’s up to the player to weigh that.

Maneuver cards are functionally the player’s task force. Most of them represent conventional military units like ships, aircraft, infantry, logistics, etc. These cards deploy, move, and fight on the game’s battlefield. Enabler cards are enhancements to these normal unit cards; Enablers like small drones, tactical action officers, or jamming pods make either the host cards, or all the cards in the host unit’s domain, more capable in some fashion. Information units are a unique type of card that only deploy to the Information domain, and I took care not to prescribe whether Information units are specific people, machines, or data. Information units represent an amalgamation of all these things; the point is that, while information capabilities are more nebulous than something as obviously kinetic as a missile cruiser, things in the Information domain can still affect activity in terrestrial domains. Hackers, cyber commands, artificial intelligence—all of these are Information units players can use to help themselves or hinder their opponent in the “real world” of battle.

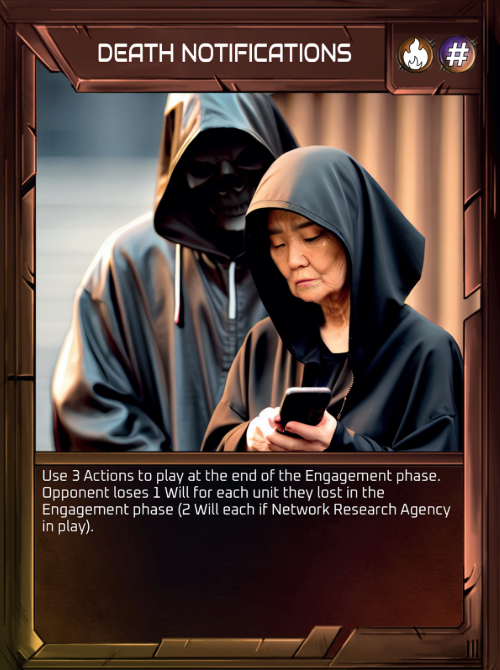

Maneuver cards also include “friction” cards, which as mentioned above are unexpected capabilities that can be played outside of the normal turn sequence to ruin your opponent’s plans. Some “friction” cards represent kinetic actions like a car bomb. However, many enhance effects in the Information domain, and in some cases, if a player has a certain Information unit in the Information domain, these “friction” cards can either be deployed more cheaply or have a more powerful effect.

A final type of Maneuver card are what I’ve called “focus” capabilities (focus is a term lifted from MCDP-1). Focus cards are powerful asymmetric advantages but they require an investment of Action cards at the very beginning of the game, and those Actions cards are permanently unavailable to the player for the duration of the game. I did this to represent capabilities that have to be cultivated long before the battle starts—for example, the Blue player has a “focus” card called NCO Leadership. A good non-commissioned officer doesn’t have a switch on their back that you can flip in the heat of combat to make them good leaders; you have to invest in that years ahead of time, keeping an eye open for promising leaders among junior Marines and then promoting them, sending them to good PME schools, and placing them in positions of responsibility where they can practice leadership and grow in their role. So I reflect that in the game by requiring players to permanently dedicate Actions cards to using the “focus” capabilities as a simulation of the resource investment it takes to train a good NCO.

Aside from Action and Maneuver cards, the game includes two types of cards that create the battlefield the Red and Blue players fight on. Domain cards depict various types of terrain, like maritime, land, or urban terrain. Some Domain cards can affect movement or modify defensive values. Urban Domains include an extra modifier that generate a penalty in “will to fight” for any player that decides to initiate combat there. I did this in reaction to how I’ve seen a lot of wargames depict urban areas, which is essentially to treat them as modifiers to mobility or attack/defend values, but which give no consideration to the human beings that actually live there. So each Urban domain has a built-in penalty to reflect the harm inflicted on civilians occupying those areas, and Urban domains that represent higher population densities have higher penalties.

Finally, there are Domain Variables, which are an extra layer of cards that are randomly assigned after players create their semi-randomized battlefield of regular Domain cards. Domain Variables represent unexpected non-combat factors that apply equally to both players, and which both players will simply have to deal with during the game. Many of these are environmental factors like flooding, wildfires, or storms. The Space and Information Domains also have Variables that can affect them, like solar flares or severed underwater cables. Additionally, some Domain Variables represent key terrain on the table which, for whatever reason, has assumed some strategic significance and control of which allows a player to drain their opponent’s “will to fight” simply by controlling it.

Domain Variables are tied to specific Domain types, and I play-tested the random distribution of the Variables to ensure that players wouldn’t play on unrealistic battlefields where their every move was subject to a thunderstorm or swarms of refugees or squalls on the high seas. But there will almost always be a few Domain Variables present to add to the game’s replayability and force players to deal with the unexpected.

Grant: Can you show us a few examples of these different types of cards?

Ian: Here are several different types of cards as examples.

Example of Maneuver unit

Example of Domain

Example of Domain Variable

Example of “Friction” card

Example of “Fog of War” numbers on Action cards

Example of Enabler

Grant: What is the purpose of the Will Trackers? How is Will built and lost?

Ian: The Will Trackers capture your side’s current “will to fight,” which is directly tied to the victory condition: drain your opponent’s “will to fight” to zero while protecting your own. I deliberately did not try to define “whose” will, or at what operational level, this “will to fight” represents. It’s an abstracted representation of many different threads of human will: the individual warfighter on the battlefield, the morale across military units and military leadership, the overall commitment of the nation to continuing the fight that is unfolding on the game’s battlefield.

Both players start at 30 Will. The main way that Will is lost is—naturally enough—through the loss of units in combat. Dead comrades, dead sons and daughters tend to negatively impact the “will to fight” of those who knew the deceased. Each Maneuver unit card has an “attrition” value which is an amalgamation of the unit’s relative size and the attributes of that unit’s equipment or capabilities, and when that unit is destroyed in combat, the owning player loses Will equivalent to the unit’s attrition value.

But Will can be lost in other ways as well. There are a number of Information and “Friction” cards which can increase an opponent’s Will loss depending on the circumstances. Should key terrain Domain Variables be on the table, players can seize control of them to further drain their opponent’s Will. Using the “humanitarian aid” mechanic of logistics units is another way to drain an adversary’s Will—if a logistics unit is present in an urban Domain, it can conduct humanitarian aid for the civilians who are notionally present there. The idea is that being seen to alleviate the suffering of warfare is a powerful strategic narrative, and showing that your side cares about civilians when the other side doesn’t can undermine the adversary’s own strategic narrative about the “rightness” of their cause.

Humanitarian aid is a key way for recovering “will to fight” as well; logistics units can either drain an adversary’s Will or regenerate your own under the same logic of strategic narrative. Both have sides have an NGO aid unit that can regenerate Will doing humanitarian aid well. And again, certain Information and “friction” cards can help you recover lost Will.

”Will to fight” is going to ebb and flow for both players during the game. That’s inevitable in war—you’re going to take losses, nothing is bloodless. So this forces both players to strategize on how they are going to absorb those Will losses and then regenerate it at a sufficient rate to keep their faction committed to the cause. And this strategy may impose some hard military decisions on players; for example, logistics units can only conduct humanitarian aid in urban Domains, but providing supply lines to combat units might require moving a logistics unit away from that urban Domain. There’s no right answer for managing the ebb and flow of Will. Players will have to exercise creativity and assume risk to achieve military goals while sustaining their “will to fight.”

Grant: What is the general Sequence of Play?

Ian: Prior to the game, both players should have constructed their decks of 60 cards. For the terrain set-up stage, players shuffle their Action cards and then draw the top one; whoever has the highest generic “fog of war” number has initiative for the game. They get to go first in the terrain set-up stage, and players alternate selecting Domains that support their deck’s overall strategy. Following that, the player without initiative randomly draws several additional Domains and inserts them across the battlefield; this is where the game’s randomization and uncertainty immediately takes shape. The Domain Variable layer is then laid down, and any Domain Variables that match the Domain they land on remain in effect for the duration of the game.

Then the player with initiative begins the turn sequence. It’s an “I GO-YOU GO” format; the player goes through all the turn steps, ends their turn, then the other player goes through the turn steps. There are some opportunities where players can do things during the opponent’s turn—“friction” cards, mentioned above, is one those ways but there are a few others.

The first turn step is cycling cards through the phases of the OODA Loop to ready what Action cards the player will have available during the turn (the OODA Loop Cycle is discussed in more detail below). Then the player has the option of expending Actions to draw new cards into their hand, and/or discard cards from their hand that aren’t immediately useful to make room for new ones.

The third step is Movement to Contact—this is one of two possible movement steps in which the player can maneuver units on the battlefield. The player can spend Actions to move units; however, these units must participate in the subsequent Engagement step. There may be circumstances in which an Engagement is so massively successful that other units no longer have any targets to shoot at. But the player can only move units during this step with the intent of fighting with them.

The fourth step is the Engagement phase, where all combat happens. There are two types of Engagements: Long-Range Strikes (LRS), and Same-Domain Engagements. LRS is one “shooter” on one target; the active player declares what unit of theirs is conducting the LRS, what the targeted unit is, declares whether they are attempting to merely suppress the target or destroy it outright, spends the appropriate number of Actions (and potentially loses Will if the fight is happening in an urban Domain), and then does the adjudication necessary to see if the LRS succeeds or fails. Once that specific LRS Engagement is resolved, the defending player may now conduct an LRS of their own (assuming they have firing units in range of eligible targets, and Action cards available to use). Players can go back and forth conducting LRS against each other to their heart’s content, or until they run out of Actions (which is not necessarily wise, since they may have wanted to use Actions to do things later in the turn like additional movement, humanitarian aid, or deploy new units).

Once all LRS are complete, the active player only can then conduct Same-Domain Engagements. Rather than one shooter on one target, this compares the total offensive combat strength of all units present in the Domain together, and the player with the lower total must lose Will equivalent to the difference. A player may choose to sacrifice a unit present in the Domain rather than lose Will, and there are certain conditions where a high leadership value on one side may force a player to lose a unit from that Domain whether they want to or not.

When all Same-Domain Engagements are finished, there’s a clean-up step at the end of the phase where any cards that were destroyed during LRS are removed from the table, and the owning player loses “will to fight” equivalent to the attrition value of those cards.

The next step is Non-Combat Movement. The active player may spend Actions to move any units which weren’t moved during Movement to Contact (units can move in one movement step or the other, not both). This is also when players can spend Actions to conduct humanitarian aid with eligible logistics units in order to drain their opponent’s “will to fight” or recover some of their own.

After this comes the Deployment step, when the active player can put new units on their board from their hand by spending the appropriate number of Action cards.

The final step is a clean up step—the active player first checks to see whether they have effective control of any key terrain Domain Variables, and if so, their opponent loses “will to fight” based on the card text of the Variable. After that, any units on either side that were suppressed during the Engagement step return to normal status; any stealthy units that were revealed during the time “hide” again; and then it’s the other player’s turn to go through the turn sequence.

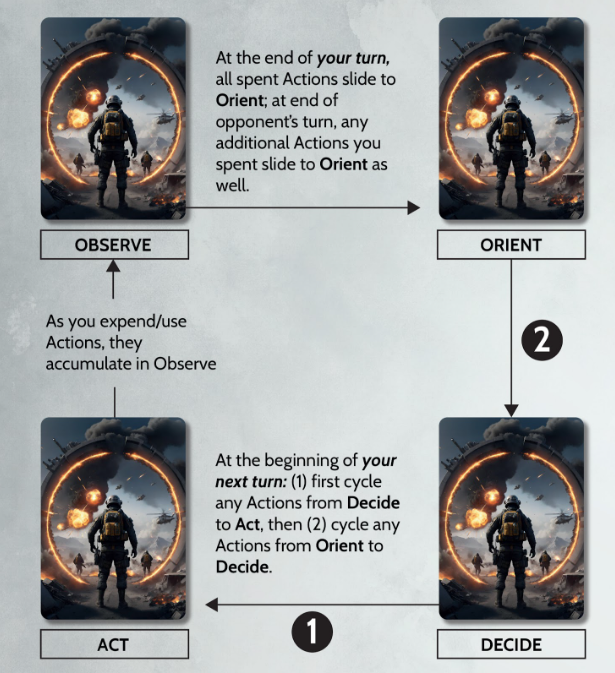

Grant: What is the concept of cycling cards and OODA Loop?

Ian: Despite the sleepless night at Origins 2024 that was the genesis of the OODA Loop mechanic, once I’d fleshed it out I was very excited about how it works in the game (and grateful for the feedback that kick-started it; don’t let your ego get in the way!).

If readers really want to delve into the history and workings of the OODA Loop, I’ve written a couple of books on it and won’t regurgitate the whole thing here. But the short version is that the Observation-Orientation-Decision-Action or OODA Loop was a decision-making framework developed by fighter pilot, military reform gadfly, and theorist John Boyd. It’s an underlying part of the Marine Corps maneuver warfare doctrine that my game tries to make tactile.

The loop is continuous and so doesn’t have a clear starting and ending point, but let’s choose one for the sake of argument to explain the cycle. You’re a Marine on a battlefield—you take the action of shooting your weapon at a target. As soon as you’ve executed the action, you OBSERVE what happens. Did you hit the target or not? Did the target move? Did other targets join it? Did something in the environment around the target change when you shot at it? You see the result of your action, you pull in the information about the action’s result along with other information you pull in from your surroundings at the time, and then you ORIENT on what to do next. Now one could write a doctoral dissertation on how ORIENTATION works, but orientation is a set of cognitive and physical lenses that you bring with you to the battlefield, through which all your observations are processed. Orientation has often been described, erroneously, as simply assessing the result of your action in the moment to think about what to do next. In reality, orientation is all of the physical and mental habits, knowledge repositories, training, and decision making ability that you have consciously and subconsciously crafted over your entire lifetime—and then applied to how you understand the observation of what action you just took.

Based on the results of your analysis through orientation, you then DECIDE what your next action in pursuit of your present objectives should be. You then ACT, doing the thing that you decided to do, and the cycle continues.

Now this is not a linear cycle and there are many different feed-forward and feedback mechanics that weave through the OODA Loop but for game purposes, I use the simplified linear cycle. At the start of the game, you can choose how many of your Action cards to have immediately available in an “Act” status, and how many in the “Decide” status as Actions that will come to you on your next turn. When you spend an Action card to do something, it moves forward in the cycle to “Observe;” you spent your Action, now you see what the result is. At the end of each player’s turn, any Action cards that were spent into “Observe” then slide into “Orientation.” My intent here was introducing a deliberate “pause” in the player’s ability to immediately regain their Actions, with the pause simulating the orientation assessment process between seeing the result of one’s acts and then deciding what to do next. It’s in this “pause” that a player can either negatively impact their opponent’s OODA Loop to simulate mental shock, or accelerate their own OODA Loop to simulate the mental resilience gained from good training, effective command and control, implicit communication, and trust between units.

As mentioned above, the first step of the player’s next turn is cycling their Actions; so first, any Actions in the “Decide” status move to “Act,” then those previously expended Actions from “Orient” shift to “Decide.” This stutter-step of activity, as it were, forces players to think about the consequences of their activity, and how they perform actions on the battlefield, in a very literal way. Ideally you establish a flow of Actions, where you are concurrently doing things, seeing the results, and preparing resources to do your next set of things. If you’re making good decisions and have the mental resilience to offset shock imposed on you by your opponent, you will always have options available to you on the next turn. However if you burn through all your Actions at once without thinking about what you want to do next, or if poor decision-making means your opponent is able to repeatedly shock your OODA Loop, you’ll find that your decision-making process, and thus your freedom to do the actions you want to do, becomes delayed, constrained, or exhausted.

It’s incredibly difficult to replicate the richness of human decision-making on something the size of a playing card, but the OODA Loop as a distillation of the decision-making process provides a useful “snapshot” framework, and since that framework also happens to underlie the warfighting theory of Marine Corps doctrine, I’m glad I found a way to include it in the game as a key feature of how players do things on the game’s battlefield.

Grant: Why have you decided to use AI art? How would you address those who have concerns?

Ian: Wow, there are a million different answers I could give to this, and in other venues I’ve made a good-faith effort to provide answers because it’s a current topic within the gaming world, one that generates strong emotions, and one that, frankly, some people will never accept my answers on because they’ve decided at the outset that there are only black and white sides and are uninterested in more nuanced discussion on it. I’ll give a few of those answers here, and readers can decide if they want to read an attempt at a good-faith answers, or simply move on after answer #1.

Answer #1: there’s a small but highly vocal population in the game design world who have made it quite clear that they hate any use of AI at any point in game design, aren’t interested in why designers might use it, and have said they will boycott any games that use generative AI. Very well—don’t buy my game. Nobody’s ever forced me to buy a game, I make my own decisions about games I do buy, and I don’t buy every game that’s available. If the use of generative AI is a deal-breaker, don’t buy my game and go buy someone else’s.

Answer #2: when the controversy really took off over use of generative AI in game design—roughly about the time news got out that a module for Terraforming Mars was using it—I took the critiques seriously and devoted a good amount of written and recorded effort to explain how and why I used it in my game. I’d encourage readers to look at those items because I go into much deeper detail on my design process, and they reflect my thoughts at the time the controversy bubbled up (mid-late 2024).

Answer #3: Realizing not everyone wants to watch two hours of video or read an even longer article, I’ll do my best to provide the short version.

Integrating generative AI products supported my design philosophy for the game: give the players an environment to explore the challenges of modern and future warfare. There was a period in my earlier design stages when I was initially using it to support my highly erratic and zero budget prototyping schedule. However as I got deeper into play-testing, the generative AI artifacts in the game assumed greater importance in helping my game achieve its educational objectives, as well as solving a paradox in the fundamentally analog character of a card game.

I wanted to make a game where Marines, and others, could grapple with modern and future warfare— and artificial intelligence is already part of warfare today. From Ukraine to Gaza, for good or ill, AI has already been deployed to real-world battlefields, and the various military use cases for AI are only growing. But I had no way to magically make card mechanics or rules that performed in the same way as an AI or LLM. So rather than put AI “in” the game, I put AI “on” the game. Every card the player holds in their hand has an image that’s an AI artifact; every action they take has an AI sheen to it.

I also found that the visual style of the images supported my goal of presenting the players with a future world. The future is by definition undefined; we don’t know what it’s going to look like, it’s hazy, it could unfold across many different trajectories. The future is literally another world, one we don’t yet live in. The generative AI imagery I used captured that “otherworldly” aspect very well—objects look familiar, plausible, but just different enough from the present day that they appear to occupy a world that’s not quite like ours. That’s the future: a world not like ours today.

Throughout playtesting, I found that regardless of the audience—military members, experienced game designers, regular gamers—playtesters liked the visual aesthetic of the cards, including the AI imagery, as much as I did. And I was completely transparent about where I got my imagery when playtesters asked. I got lots of playtesting input on card layout, rules mechanics, balance, etc., and I took all that seriously. I adjusted #Maneuver Warfare based on that feedback—no matter when in the design process I received that feedback, see the Origins 2024 story—and if there had been a trend of playtesters finding the AI aesthetic distracting or unpleasing, I would have given serious thought to finding some other type of imagery to use. But I never got any feedback of that type. Modify the rules, shift icons around, reduce the amount of card text—I got plenty of opinions on those things. But when it came to the visual aesthetic of the game, what I got my from playtesters was almost always: “the cards look great.”

Among the criticisms I’ve heard of generative AI in game design is that it somehow “dehumanizes” the design process, removing the human touch from game creation. I’m not sure what to make of that argument because from my own very human perspective, I’d have gotten a lot more sleep in the design process if I’d simply offloaded everything to an AI. Because the imagery aside: every other design aspect of this game, from my first kernel of an idea to approving the final design proof, was done by humans. Card design and iconography, prototyping, rules development, play-testing, proof editing, marketing, background research, play-test logs and data recordation, designing the game box, driving and flying my prototypes to everything from game conventions to small PME events for more play-testing—humans did all that.

Once I shifted from my own prototyping to final production design, I worked with a real live human graphic designer whose own ideas had a huge impact on the final card layout and iconography. This game has her fingerprints on it just as much as mine. At the end of the day, AI’s contributions to the game pale in comparison to the endless hours of human development that put this thing on the table.

So it was part of my design philosophy for this specific game. I’ve designed, or am in the process of designing, several other games on different topics, and I’m not using AI in any of them because I have different design philosophies for each. It’s entirely possible that I never again have a design philosophy that sees AI integration as vital to the game’s intended lessons or player experience.

That’s the short version. Readers who’d like a longer one can check out the links above in answer #2. And if readers don’t agree with my design philosophy, then I’d refer them to answer #1.

Grant: What type of experience does the game create for the player?

Ian: I would never claim that #Maneuver Warfare simulates war—no game does that, ever. What I wanted players to experience was some of the strain of decision-making that shapes battlefield thinking, and do so with some of the tools either they, or their possible adversaries, might have on the battlefield. So I hope players experience the agony of making decisions with limited resources, uncertain information, the constant friction of opponents doing the unexpected, and how their decision-making cycles can be disrupted or accelerated based on their battlefield choices. And I hope there’s enough variety in the game with the card options that each playthrough presents new decisions to make, inculcating new learning every time.

And I want it to be fun. I hope that Marines and other Servicemembers dive into its competitive aspect, talk s**t to each other while they’re playing, and immediately demand a rematch if they lose.

Grant: What other games are you working on?

Ian: There’s a lot in my pipeline. I have several future modules—Norway, Ukraine, and a pirate/insurgent faction—for Littoral Commander that I’ll be upgrading from the original prototype dice system to the commercial D20 system. I have a couple of other games in early prototyping: a “UFO” hunting game with one player trying to shoot down what in modern parlance we now call Unidentified Aerial Phenomena (UAP), and the other flying the UAP and trying to avoid detection. The working title for this is What the **** Is That Thing?, which is an actual quote from a U.S. military pilot’s cockpit recorder after observing the strange behavior of a UAP. I’m also working on an abstracted amphibious landing game where the Red player has to grapple with constraints in amphibious lift, and the Green player has to stop the landing while at a severe firepower disadvantage.

Thank you so much for your time in answering our questions Ian. I very much enjoyed reading about your thoughts and process of designing the game. I also very much enjoy your inclusion of real world military aspects to create a very interesting simulation of modern warfare. I am very much looking forward to playing the game in the near future!

If you are interested in #Maneuver Warfare, you can order a copy for $30.00 from The Dietz Foundation website at the following link: https://dietzfoundation.org/product/maneuver-warfare/

-Grant

I played a prototype of this in October 2024 and really enjoyed it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think that it does look very interesting. Seems to have real teeth even as a card game. Looking forward to it for sure!

LikeLike