A few years ago, we did an interview with David Gómez Relloso covering his well thought of Crusade and Revolution: The Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939 from Compass Games that was getting a deluxe edition and on Kickstarter at the time. Since that time, we have played the game and really enjoyed it. Recently, I spoke with Francisco Ronco and he informed me that his company Bellica 3rd Generation was doing a new game by David called An Impossible War. I reached out to David and he was more than interested in providing us some information.

If you are interested in An Impossible War, you can pre-order a copy from the Bellica 3rd Generation website at the following link: https://bellica3g.com/en/product/una-guerra-imposible/

Grant: David welcome back to the blog. What is your upcoming game An Impossible War about?

David: An Impossible War is a historical simulation game about the First Carlist War, a civil war that devastated Spain between 1833 and 1840. After the death of King Ferdinand VII, the succession conflict between his daughter Isabella and his brother Carlos caused a confrontation between the supporters of liberalism and the defenders of tradition (something common in Europe at that time).

In Navarre and the Basque Provinces -the North- the main campaigns, battles and sieges took place, so I decided to focus the game on that theater of operations and on the decisive years of the war from 1834 to 1838.

Grant: Why was this a subject that drew your interest?

David: I was born in San Sebastián, a city that experienced the Carlist Wars firsthand, so it was a topic close to home that seemed interesting to me. It is not a well-known topic in Spain, despite its significance in the 19th century, perhaps because the 1936-39 Civil War overshadowed the earlier ones.

Furthermore, it is a topic that has barely been reflected in wargames. I wanted to play it on an operational scale, and to do so, it was necessary to design a game that suited my preferences and represented a serious simulation of the conflict.

Grant: What is your design goal with the game?

David: First, create a good simulation of the conflict. The historical background is what characterizes and differentiates our hobby from other board games, so it is very important to take care of this aspect. As Francisco Ronco (its editor and developer) says, “we design cardboard simulators.” I agree and I think that it is important that when playing, we feel like we are immersed in a specific historical episode, and not just any indeterminate conflict.

On the other hand, I do not forget that we design board games, recreational entertainment that allows us to enjoy good times in the company of other players. So it is also important to take care of the playability and the balance between sides. The game has to be fun!

Grant: What from the First Carlist War was important to model in the game?

David: It was a very particular war, unlike other more conventional ones. It followed a Napoleonic style of warfare, but on a much smaller scale and with limited resources. To give an idea, at its peak, the Carlist Army of the North had 35,000 men, little more than a Napoleonic corps, and the liberal troops opposing it almost quadrupled that number.

Beyond the numbers, it is worth highlighting that the Carlists were aware they were facing an asymmetrical war and chose to take advantage of the benefits their territory afforded them. They applied the “petite guerre” (small war), avoiding confrontation unless it was on their terms, using guerrilla warfare and resorting to coups de main, ambushes and surprise attacks.

The government forces were superior in number, but they suffered a hell similar to that endured by Napoleon’s soldiers in Spain 25 years earlier. The border with the territory controlled by the rebels measured 500 kilometers and needed to be garrisoned. Penetrating enemy territory was a logistical nightmare, one that required blind advances against an opponent who seemed to know everything.

The cities were under government control and were the Carlists’ main focus throughout the war. They failed to capture any, but several were blockaded and others were besieged and assaulted. Bilbao, in particular, suffered two sieges and was in serious danger. Siege warfare, in general, was important because fortresses were the only way to maintain permanent control over the territory.

The Carlists were not content with simply dominating their own territory. There were other rebel zones (especially in Catalonia and the Maestrazgo), many guerrillas active throughout Spain and the ultimate goal was to achieve a regime change by crowning their pretender, Don Carlos. Therefore, they launched expeditions from the north, seeking to foment rebellion and expand their territory. The expeditions failed, but they caused headaches for the liberals.

All these aspects (and several more) have been taken into account when designing the game.

Grant: What sources did you consult about the details of the history? What one must read source would you recommend?

David: I read different books, articles and magazines, and also listened to podcasts. Of course, there are many sources, and I have only consulted a small portion of them, but I have tried to use high-quality materials. A wargame is not a typical academic work, but I think that An Impossible War achieves a good level of historical simulation.

My two reference books are by Spanish authors and have not been translated to English: The Carlist Army of the North (1833-1839) by Julio Albi de la Cuesta and The First Carlist War by Alfonso Bullón de Mendoza. In English, Osprey’s book Armies of the First Carlist War 1833-1839 by Gabriele Esposito is an excellent start.

Grant: What other games did you draw inspiration from?

David: It was not just one title, but many, that inspired and helped me while designing An Impossible War. Obviously, the first ones that come to mind are some block wargames.

I would like to take this opportunity to make a digression regarding blocks. Many people consider them a genre in themselves, but I think that is a mistake. Just as it would be to consider cardboard tokens or cards a genre. Blocks are simply a tool that designers use in many different ways. There are block games that are similar, but also many others that are quite different.

Columbia Games’ titles are a referent when it comes to using blocks. Napoléon: The Waterloo Campaign, 1815 is one of my favorites and a source of inspiration. However, my desire to increase the simulation has led me to add rules and mechanics that give greater prominence to the historical background. This meant increasing the complexity and length of the game, but I believe both are still more than reasonable.

Although it is not a card-driven game, I also wanted to introduce that component, which I find very attractive and allows for an easy introduction of historical events and unexpected occurrences, increasing replayability.

Grant: What has been your most challenging design obstacle to overcome with the game? How did you solve the problem?

David: There have been several challenges, but to keep things short, I will only mention one. The First Carlist War had a very particular and characteristic aspect that, if ignored, would have resulted in a failed simulation: the expeditions.

Throughout the conflict, successive Carlist forces were launched from the north toward the rest of Spain. These expeditions played a leading role, and it was necessary to give them presence in the game.

To achieve this, it was necessary to include a map of regions and rules to govern their movement, logistics, and influence. Consequently, a way for the liberal player to hunt them down had to be added.

The map of regions has an additional benefit: it allows the Carlist uprising to be reflected in the rest of Spain. Let’s not forget that the game focuses on the northern theater, but the war affected, to a greater or lesser extent, the entire country. Just as I was clear from the outset that these aspects had to be present in the game, I also understood that it would be necessary to abstract and simplify them, preserving the simulation without increasing complexity or resulting in a bloated rulebook.

Grant: Why did you feel a block wargame was the best vehicle to tell this story?

David: Blocks are a useful and convenient tool for reflecting the fog of war and for scaling the number of steps (from 1 to 4) for a unit. I like how they work in “open front” wargames, as is the case here.

The peculiarities of the First Carlist War (some of which I have already mentioned) led me to believe that blocks would be the best option for the type of game I wanted to design. First-person accounts from Liberal officers emphasized their intelligence problems and the fact that they were often forced to operate blindly. The Carlist numerical inferiority was mitigated by the enemy’s lack of knowledge of their true number and location.

Furthermore, the chosen scale allows for the right number of blocks—neither too many nor too few.

Grant: What different types of units are included? Do any of these units provide special abilities or attacks?

David: Infantry and cavalry are represented by blocks. Artillery and logistics units are represented by counters.

There are different types of infantry units. In the case of the Liberal Army, the typologies typical of a Napoleonic-style army are used: Royal Guard, line infantry, light infantry, etc. In the Carlist Army, units are associated with their province of origin: Navarre, the Basque Provinces, or “Castilians” (soldiers from the rest of Spain).

Liberal cavalry is varied (guard, line, light, etc.). The Carlists were always short on them and have few mounted units.

Artillery is divided into two types: field artillery (larger pieces) and mountain artillery (smaller cannons that were easier to transport). It had little significance on the battlefield, but was essential for siege warfare.

Finally, there are two types of logistics units: supply trains (wagons and mules) and backpacks (the limited resources carried by the soldiers themselves). The quality of the troops varies on both sides, although it is somewhat better in the Carlist army, which also has elite units. The Liberals have acceptable regular units, but also provincial regiments that represent raw recruits or poorly trained soldiers.

Under the Treaty of the Quadruple Alliance, the Liberal government received military aid from Great Britain, France, and Portugal, whose troops, of varying quality, also appear in the game.

Combat units do not have “special abilities”. However, the value of their characteristics (efficiency and morale) has a direct impact on combat.

Grant: What is the purpose of the Logistics units?

David: I wanted logistics to be an important aspect of the game because it was crucial in this war and because I believe it is an aspect that should be present in the design of any wargame. In the north, the Carlists had fewer problems because they were in their own controlled zone, but for the liberals, supplying the columns that ventured into enemy territory was a nightmare. In contrast, Carlist expeditions that moved to other Spanish regions were forced to be constantly on the move and rely on the terrain, with adverse results for their cause.

Combat units can obtain supplies from their space, depending on which one and where it is (which abstractly simulates logistical networks), but this supply has its limits, and maneuver armies must rely on logistics units to conduct campaigns.

A lack of supply has draconian consequences, and players (especially the Liberal) must play with this factor in mind.

Grant: How does combat work in the game?

David: Combat is an aspect I devoted a lot of work to during the design phase. I already mentioned that the First Carlist War was not a conventional war, but rather a conflict of guerrilla warfare, skirmishes, brief actions, and sieges. There were few battles worthy of the name.

Consequently, there are two types of open-field combat: skirmishes, when one of the combatants has few units involved, and battles, when both players commit a significant force.

Skirmishes are resolved quickly: players reveal their units, play cards, roll dice, apply casualties (which are usually few), and determine who retreats.

Battles have their own rules and a board (the battlefield) where both armies are deployed. They can last up to three rounds, during which players alternate activating units. Morale becomes important, casualties increase, and reinforcements can arrive. A complete defeat can give the opponent a victory point.

A battle is an exciting moment and can have great significance. Once the rules are known, players will resolve a battle fluently. But they are rare; actually, if they were common, they would hinder the game and it would not work. Intensive playtesting has determined that there is an average of one battle per year, sometimes even less, rarely more.

Controlling the tempo of combats, when to engage in a battle and when to avoid one, is an interesting aspect of the game that players must learn to manage.

Grant: What is the role of the Leaders and what benefits do they provide?

David: Many wargames include leaders in tokens or blocks. These officers tend to be very important in the game, for better or worse, depending on their abilities.

In An Impossible War, I did not want to give that prominence to the leaders. There are games where everything is centered on having the right leader at the right time. I preferred to let the players lead their troops. As we have seen before, the quality of the units varies, but here there are no leaders with “superpowers” nor useless officers.

Obviously, as in any conflict, there were figures who stood out for their skill or their ineptitude, and there are aspects of both armies that derive from the actions of those leaders. For example, the genesis of the Carlist Army of the North could not be understood without the figure of Zumalacárregui, who was its organizer and inspiration. And in the second half of the war, the liberal army cannot be dissociated from General Espartero. I did not want to completely ignore these characters, so several of them appear on the game cards and can influence operations when played.

Grant: How does the game use cards?

David: This is not a card-driven game. Here, cards are a complement. In their phase of each turn, each player draws a card from their deck and either resolves it immediately if it is an event, or keeps it in their hand to be played later.

Cards are a design tool with several uses: introducing historical events, influencing operations and combat, representing the element of surprise, and so on. They also increase replayability, since a card may appear in one game but not in another, and if it does, it will not always be available at the same time.

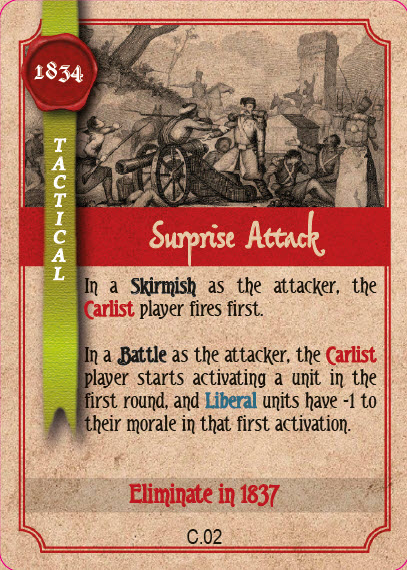

Grant: What different types of cards are included?

David: There are three types of cards:

- Event: Played as soon as the player has taken it.

- Operational: Can be played when the conditions stated on the card are met, during the player’s own phase or, sometimes, during the opponent’s phase.

- Tactical: Can be played in combat as stated on the card.

- Can you share a few examples and describe their use?

Example of Liberal Event Card: Mutiny.

As soon as the Liberal player draws this card from their deck, a mutiny breaks out in one of their cities or regions, at the Carlist player’s choice. Liberal troops present may not act for the entire turn as they are disrupted due to the event. This can cause a temporary reprieve for the Carlist player and be a very welcome card.

Note: This was a serious problem that the Liberal army suffered throughout the entire conflict and which harmed the Liberal player in unpredictable ways. These types of cards will create an uncertainty about the disposition of armies and players must plan for their appearance and deal with the consequences. And yes, a card in your own deck may harm you!

Example of Carlist Operational Card: Capture of Enemy Code.

The Carlist player can evade or intercept automatically and for free with the play of this card without the need to roll of spend any Command Points, that is, they can escape from an enemy force to avoid combat, or they can intercept enemy movement to force an engagement on their terms. Tactically, these type of cards are very important to the Carlist as they wish to fight on their terms and under the circumstances that are best for their possibility of victory.

Note: The rules allow evading or intercepting under certain circumstances, for a cost and by rolling the die. The advantage of this card is that the action is free and automatic.

Example of Carlist Tactical Card: Surprise Attack.

If the Carlist player plays this card in attack, they will shoot first. The advantage of this card is that shooting first, thereby reducing the units attacking, leads to fewer hits on the attackers side and can be the difference between winning and losing the battle.

Note: In combat, the defender shoots first. This tactical card modifies that rule in combat, reflecting the Carlists’ ability to ambush and surprise attack the enemy.

Grant: What is the objective of each player? How is victory achieved?

David: There are common objectives for both players: the main objective is to control the main cities and towns on the map. Also, to win overwhelmingly in battle. At the end of each year, the fortresses held by the liberal player in Carlist territory are counted, which gives an idea of the government’s or rebel’s success.

From there, each player has their own path to victory. The Carlist player increases their prestige by besieging cities and launching expeditions. They also benefit from the growing Carlist uprising in the rest of Spain.

The liberal player will be busy countering Carlist prestige, putting down uprisings, and hunting down expeditions. They have the advantage that, in the long run, war fatigue will affect the enemy.

To determine the winner, a marker is used, which moves on a table toward one side or the other based on the victory points each player earns, for the reasons listed above.

If the marker advances too far toward one side, an automatic victory may result. The Carlist player also wins the moment he controls two cities (historically he failed to capture any).

Grant: What different scenarios are included? How do they differ?

David: The game includes three scenarios:

- Zumalacárregui’s War (1834-36)

- Espartero’s War (1836-38)

- Entire War (1834-38)

The Entire War scenario allows players to play through the entire conflict. Players will explore its various stages, from the beginning of the uprising, the mobilization of both armies, the expansion of Carlism throughout Spain, the first expeditions, and so on. Later, the tables will turn, and the liberal player will take the initiative, improving the quality of his troops and obtaining more resources. Despite war fatigue and the first signs of decay, the Carlist enemy will never cease to be dangerous.

Zumalacárregui’s War (the great leader and organizer of the Carlist Army of the North, who died prematurely during the siege of Bilbao in June 1835) covers the first three years of the war, the sweetest moment for Carlism.

Espartero’s War (who took command of the liberal army at the end of 1836 and achieved victory, becoming a leading political figure in Spain in the following years) covers the last three years of the war. The Carlist army begins at its peak, but a turning point in favor of the liberal forces arrives.

A short scenario can be played in a morning or afternoon session. The full war will take a day.

Grant: What is the General Sequence of Play?

David: Each year is divided into five turns, and a game turn is organized as follows:

1) Reinforcement Phase

2) Carlist Uprising Phase

3) Order of Play Phase (until 1836 inclusive the Carlist has the initiative, then the Liberal)

4) First Player Phase

- Take a Card

- Complete Fortress construction

- Take an Action Point marker

- Deploy/conceal Artillery (Carlist player only)

- Actions

- Combat: Skirmishes, Battles, Assaults, and Sorties

- Supply (own units only)

5) Second Player Phase (as for first player)

6) Victory Check Phase

Grant: How are units activated? What is the role of Action Points?

David: At the start of their phase, the player randomly draws an Action Point token. These points are the “fuel” they spend to perform actions: build fortresses, obtain replacements, etc. And, of course, activate spaces.

Activated units can move. Their movement allowance will depend on how many units move together and the roads used (main or secondary). The liberal player must roll on a table. Cavalry is faster and field artillery is slower.

If units enter a space occupied by enemy units, a combat will ensue (skirmish or battle, depending on the number of troops present).

Instead of spending them, the player can save Action Points, converting them into Command Points. Command Points can be converted into action points in a later phase, they are used to contest the initiative and to carry out interceptions (which, unlike in other games, are not free here).

Grant: What is the layout of the board?

David: The main map (or map of the north) is point-to-point, showing spaces connected by main or secondary roads.

For victory purposes, the most important spaces are the five cities and several major towns. There are also two “Carlist refuges,” areas where the rebels were particularly favored by geography and popular support.

The terrain is simple: each space can contain rough or open terrain, depending on the relief of its area. Much of the northern geography was rugged, which played an important role in favor of Carlism, as it mitigated three of the advantages of government troops: their superiority in numbers, cavalry, and artillery.

The spaces at the western, southern, and eastern ends of the map have connections to regions on the map of the rest of Spain, which can be used to move from one map to another.

The map of regions is smaller and simpler. It consists of nine large regions that cover large territories. As previously mentioned, this map serves to record the spread of the Carlist uprising, to enable Carlist expeditions to operate, and for the liberal player to hunt them down.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that the map includes various game tables (year, turn, initiative, victory points, Carlist prestige, etc.), as well as a lot of information about commonly used rules, so players don’t need to consult the rulebook.

Grant: What optional rules are included? Why did you want to make them optional and not part of the base game?

David: The game includes a good bunch of optional rules. There are pro-Carlist, pro-Liberal, and neutral ones.

To answer the second question, I will quote the note that precedes the optional rules section in the playbook:

The game has been tested with its basic rules without adding any optional rule. The following rules are offered to players to use at their discretion. They modify the balance of the game in favor of one or other side, increase the detail of the historical simulation, add counterfactual events or, simply, spice up the gaming experience. We discourage their use in the first few games – later, experienced players can use them at their own risk.

Grant: What do you believe the game does really well in modeling the war?

David: As it has become clear throughout this interview, historical simulation is an aspect that I consider crucial when designing a wargame. With so many board games at our disposal, there are titles with excellent mechanics, systems, and matrixes. But when it comes to wargames, many of us demand a well-crafted background, in addition to working and being fun, of course. For a “sticked theme”, we already have eurogames.

I think that An Impossible War manages to transmit and recreate what the First Carlist War was, and places players in the position of those who led both armies. With their advantages and weaknesses, with the tools they had to deal with, and in a particular theater of operations. An unconventional war, frustrating for both sides.

To mention something more specific, I am very satisfied with how the Carlist expeditions work. A specific aspect of the war that occurred throughout almost the entire conflict. The Carlists placed great hopes in these columns they launched from the north toward the rest of Spain, although their overall result was a failure.

Nothing obliges the Carlist player to organize expeditions. Knowing their risks and opportunities, they will decide whether to do so. Likewise, the liberal player will choose how to react to them. All this is done with rules that abstract and simplify to avoid complicating the game.

Grant: What has been the experience of your playtesters?

David: The testing phase is absolutely vital in the development and fine-tuning process of a wargame. Dozens of volunteers have participated in test games of An Impossible War, and without them, the final result would undoubtedly have been worse.

The testers’ involvement has two facets:

On the one hand, they are essential for verifying that the rules can be understood, detecting typos, testing the mechanics, and balancing the game.

On the other hand, it is important to obtain their subjective opinions on the playing experience, discuss with them, and receive criticism and suggestions.

The vast majority of testers are satisfied with the game, although, naturally, some have liked it more than others. Sometimes players have made excellent contributions to improve the game. Other times, they made suggestions that I had to discard, for various reasons. This is the ultimate privilege and responsibility of the designer.

In my short experience as a designer, I have always wanted to create a game that fits my preferences and that I look forward to playing. It is very satisfying that other players also enjoy it and share their positive feedback with me.

I do not want to end without paying tribute to the game’s developer and editor, Francisco Ronco. He’s one of the best Spanish authors, and working with him has been exceptional. His partner, Daniel Peña, an experienced game analyst, has been the other pillar of this project.

Grant: What other designs are you working on?

David: None right now. I do not have the ability to work quickly or on more than one project at a time. I will soon start working on the 3rd edition of Crusade and Revolution. The Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939, so it will be a while before I even consider starting any other design.

Occasionally, if time allows, I like to playtest games or review rulebooks, which is also satisfying.

Thank you very much!

If you are interested in An Impossible War, you can pre-order a copy from the Bellica 3rd Generation website at the following link: https://bellica3g.com/en/product/una-guerra-imposible/

-Grant

So happy to see more about Spain’s history and Spanish designers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

We love to have our Spanish friends on the blog.

LikeLike

FWIW, there was a previous game on the Carlist War in Alea magazine back in ’07 and they were working on a standalone reprint, but no idea where that is at the moment

https://boardgamegeek.com/boardgame/31776/dios-patria-y-rey-the-carlists-wars-1833-1840/credits

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for pointing that out.

LikeLike