Several years ago, we became aware of a new upcoming game that tackled the politics and processes of the U.S. Supreme Court in a 2-hour game. At that time, I reached out to the designer Talia Rosen to get some information on the game and have her answer our questions. Due to several circumstances, 2 years has now come and gone and now the game is finally prepared to go onto Kickstarter soon. Talia reached back out to us and asked if we would still do the interview and of course we said yes. I really appreciate Talia and her effort in doing this but also with her great insights into the game and how it plays.

If you are interested in First Monday in October: The U.S. Supreme Court, 1798-2010, you can check the project out at the Kickstarter preview page at the following link: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/fortcircle/first-monday-in-october

*Please keep in mind that the artwork and layout of the various components shown in this interview are not yet finalized (although they are nearing final art) and are only for illustrative purposes at this point. This means that things with the components might change and rules and other details may still change prior to publication.

Grant: First off Talia please tell us a little about yourself. What are your hobbies? What’s your day job?

Talia: My main hobby is of course board games, which I’ve loved since I was a little kid. Growing up, I was always begging family and friends to play board games with me, and this only grew when I later discovered Diplomacy and Settlers of Catan in high school in the late 90’s. I founded my first board game club in law school in 2004 and started collecting games in earnest then

I do also very much enjoy cooking, video games, podcasts, skiing, and playing tennis.

I’ve worked as an attorney for the Public Broadcasting Service for over 15 years now. I’m passionate about public media, and I’ve had the privilege of working on countless different projects over the years.

Grant: What motivated you to break into game design? What have you enjoyed most about the experience thus far?

Talia: After moving from New York to D.C., I met Jason Matthews (designer of Twilight Struggle) and started playtesting prototypes with him. I also started attending the Gathering of Friends with Alan Moon, where I had the opportunity to playtest games with Vlaada Chvatil, Tom Lehmann, Matt Leacock, William Attia, and others. I found that I really enjoyed trying prototypes and giving feedback on areas for potential improvement. I had no intention of designing my own game, until Jason Matthews mentioned off-hand that he could not figure out quite how to design a game with a Supreme Court theme that would cover the arc of history. I stewed over that for years, very gradually jotting down ideas, and shelving those ideas for years.

Ultimately, I rediscovered those notes when I was moving to a new apartment, and I happened upon a New York Times article about the designer of Wingspan at the same time, and the convergence of those events made me wonder if I could do it too. I brought a very rough prototype to a convention in early 2019, expecting and/or hoping to be done with it, but the reception and encouragement was so positive that I felt compelled to dive into working on the idea for First Monday in October more. I brought the game to a day-long “Break My Game” event in D.C., which was similarly uplifting and motivating.

I’ve enjoyed getting to play a game that combines most of my favorite concepts in gaming over and over. And I’ve really enjoyed seeing the game click with strangers!

Grant: What designers have influenced your style?

Talia: Jason Matthews, Vlaada Chvatil, Reiner Knizia, Mac Gerdts, Wolfgang Kramer, and many others. I like games with a limited action menu (like Stephenson’s Rocket), area control (like El Grande), and small quick turns that build a larger tapestry (like Imperial and Hansa Teutonica).

Grant: What do you find most challenging about the design process? What do you feel you do really well?

Talia: The most challenging process has been adjusting the strength of the actions to ensure that they are balanced and that each player’s decisions will ultimately be challenging. It’s critical to me that players be torn in multiple directions, wanting to do more actions than they can and therefore having to make difficult choices. I suppose this is the most challenging part, and I think what I’ve managed to ultimately do really well.

Grant: What games have you designed?

Talia: None. My shelves are literally overflowing with wonderful games that others have done all the work on, so I’ve always intended not to design a game. But the idea for First Monday in October would not let me be, so after years of assuming someone else would create a Supreme Court game that I could simply enjoy, I finally decided to try doing it myself.

Grant: What is the design goal of your upcoming First Monday in October?

Talia: First and foremost to make a game that I personally enjoy. Given how many times I need to play it to finetune the rules, I need to love playing it for that to make sense. Second, to demonstrate that a German-style eurogame can be driven by its theme, that the theme can be unique, and that the game can be historical yet balanced.

Grant: What was your motivation to design a game on the U.S. Supreme Court? Why did you think this was a topic well suited to a game?

Talia: The history and institution of the U.S. Supreme Court is just so fascinating that it’s hard for me to imagine not wanting to design a game about it. This is a small deliberative body that, at its finest, moves society forward and safeguards “discrete and insular” minorities against the “tyranny of the majority.” And yet, it’s a remarkably antidemocratic institution that leverages enormous power. I did not originally think that the topic was necessarily well-suited to a game, but I’ve chipped away at it for a decade, and I think I’ve found the diamond in the rough.

Grant: What sources did you consult on the history of the U.S. Supreme Court and this infamous concept of the First Monday in October?

Talia: The Supreme Court’s own website (www.supremecourt.gov) and the Supreme Court Historical Society (www.supremecourthistory.org) are both wonderful resources, as is the Oyez archive (www.oyez.org).

Grant: What one must read source would you recommend?

Talia: Read the actual opinions themselves. Read Marbury v. Madison, Brown v. Board, Korematsu v. US, Roe v. Wade, Tinker v. Des Moines, etc. The remarkable thing is that the Supreme Court explains itself in great detail, and the opinions of the Justices are often much more nuanced and thoughtful than the press reports. Or for a more contemporary opinion, check out the recent 2022 decision involving Prince and Warhol (available here). Lastly, while it’s not reading, as a public media person, I also can’t help but recommend the exceptional More Perfect podcast by WNYC Studios, a “series about how the Supreme Court got so supreme.”

Grant: Players take on the role of institutions, associations and think tanks to try and influence the High Court. How does this work?

Talia: At the beginning of the game, each player is dealt 3 Philosophy Goal Cards from a deck of 24 cards. Those cards represent the potential secret identities and motivations of each player, and they include a wide range of institutions (such as the New York Attorney General’s Office, the Department of Labor, or the Catholic Dioceses) or longstanding schools of thoughts (such as Natural Law Theorists, Strict Constructionists, or The Chicago School). Each card depicts three judicial philosophy goals, such as a Federalist interpretation of the commerce clause, an Anti-Federalist interpretation of Article II of the Constitution, and a more expansive interpretation of the 1st Amendment. This gives the player a unique set of goals in the ongoing tug-of-war over shaping the composition of the Court and influencing its aggregate philosophical leanings. Over the course of the game, each player will discard one of those goals one-third of the way through the game and another goal two-thirds of the way through the game, leaving them with their actual role or identity to reveal and score for at the conclusion. Ultimately though, this is not the biggest source of points, which can also be earned in many other public ways, so it’s just one piece of the puzzle.

Grant: What philosophies are at work here and how do they get represented in the game?

Talia: The core of the game revolves around 4 Judicial Philosophy Tracks, which each represent a different part of the Constitution, and the meaning of which have been litigated over the past 200+ years. Those tracks are: (1) Commerce Clause (Article I, Section 8) from which a vast amount of Federal legislation flows to regulate commerce among the states; (2) Executive Power (Article II) which enumerates the powers of the executive branch; (3) Free Speech (1st Amendment) that Congress may make no law abridging a person’s freedom of speech; and (4) Equality, which represents individual equality and liberty, including equal protection and due process. When you dig into cases through history, it’s really fascinating and surprising to see how these provisions have been variously interpreted over the years, particularly the 1st Amendment.

Grant: Where did your biggest influence on the design come from?

Talia: The biggest influence certainly came from Jason Matthews and his games like Twilight Struggle, Founding Fathers, Campaign Manager, and 1989. I definitely hope that the game appeals to fans of Twilight Struggle (and that they appreciate not having to roll a die to advance on my version of the Space Race track, which is the Robing Room).

Grant: How did it shape your thoughts on translating this subject to a playable game?

Talia: The push and pull of the discussions with Jason throughout development on translating this subject to a playable game was fascinating and I think made the game better for it. Jason has been an invaluable mentor for years now. His work and his advice definitely shaped the translation of this subject into a playable game by constantly pushing me to consider how to embed the underlying theme as deeply as possible into the mechanisms of the game throughout.

Grant: The game uses cards. What different type of cards are there and how are each used?

Talia: The game includes 117 cards, which includes:

- 24 Case Cards (which are based on real historical cases, including 6 cases about each of the 4 Judicial Philosophy areas, such as 6 cases about the powers of the Executive Branch)

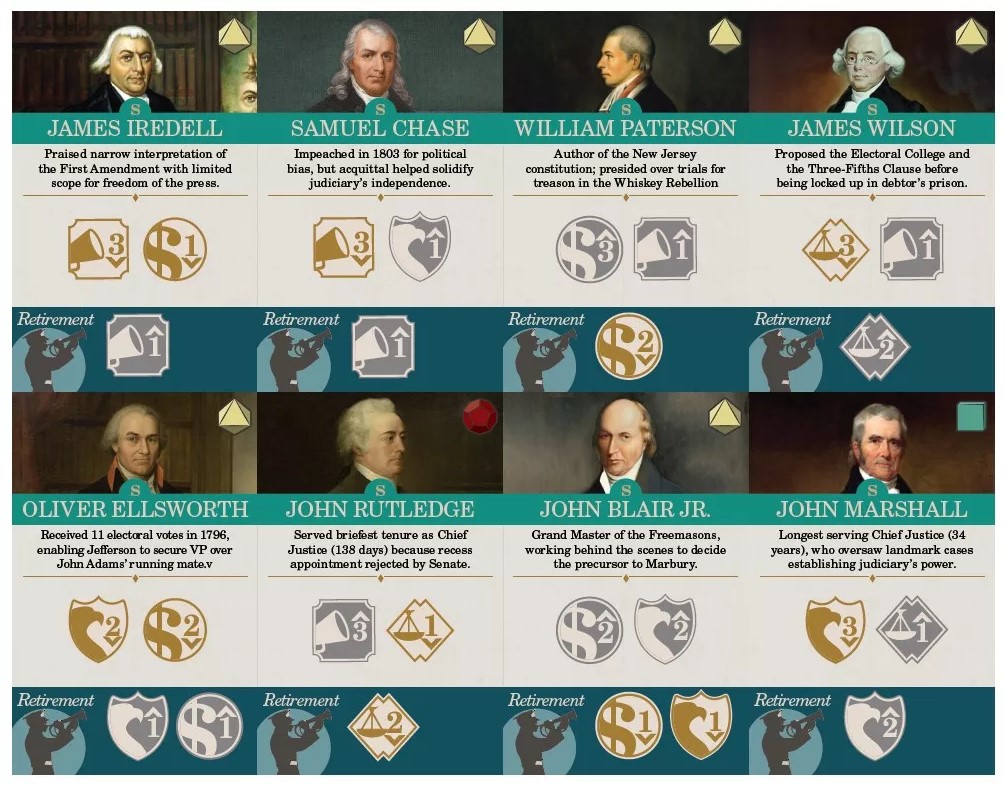

- 59 Judge Cards (which are all real historical Supreme Court Justices, but only some of whom will make it onto the Bench in any given game based on the actions of the players)

- 24 Goal Cards (as described above)

- 10 Solo Cards for the solo mode, which I’ve just recently figured out how to make work and which I’m really enjoying these days.

Grant: What is the goal of the game? How do players go about reaching this goal?

Talia: The goal is to earn the most Renown Points, which largely come from winning cases. Players can win cases by having the most clerks on the prevailing party of the case when it resolves. Case Cards are gradually added to the board and then resolve after a few rounds, so players have a few rounds to become counsel to either litigant in the case, aiming to do so for the party that they expect to prevail. Players can of course influence who prevails by shaping the composition of the Court and adjusting the Judicial Philosophy Tracks. There are also a variety of ways to earn Renown at the end of the game, but ultimately the game is largely about winning cases.

Grant: What actions are players able to take each round?

Talia: The game lasts up to 15 rounds (because it ends when either the Cases or Justices Deck runs out of cards), and in each round players get to do 3 different actions from a menu of 6 possible actions. These actions are: (1) gather influence to gain the resources needed to put clerks onto cases; (2) advocate to put your clerks onto cases; (3) retirement to attempt to remove a Justice from the Court; (4) support candidate to try to determine who will be the next Justice appointed; (5) law review article to directly shift a Judicial Philosophy Track; or (6) rest to move up the Robing Room Track for a special ability. My goal is to make choosing among these actions tough!

Grant: What is the Robing Room Track used for?

Talia: The Robing Room Track is a way to give players another option on their turns and a way to do things that would otherwise be against the rules, so for instance, the very first space on the Robing Room Track allows a player to put a clerk directly onto a Justice on the Court, and the very last space on the track allows a player to remove a Justice from the Court. There are also fun spaces related to remanding cases and asserting original jurisdiction that can be very powerful when timed right in certain circumstances. These are like events that depend on the context, but can be anticipated and planned for to some extent.

Grant: What type of Cases are included in the game? How did you decide on 24 Cases?

Talia: I decided on 24 total Case Cards because: (a) I wanted to have an equal number of cases for each of the four Judicial Philosophies; (b) I wanted the game to take about 2 hours or less to play; and (c) I wanted some variance in the deck composition but not too much. I would have loved to include more Cases, but over a few years of playtesting, it became clear that having 2 Cases per philosophy per era was the best way to meet those goals (i.e., 8 case cards per era). With players randomly removing 2 cards per era, they use 18 in any given game, and deal 3 onto the board at the start. This means that the Cases Deck has 15 cards at the start, which caps the duration at 15 rounds.

Grant: How are the Philosophy Goal Cards incorporated into the design and what type of challenge do they create?

Talia: The Philosophy Goal Cards ensure that each player is in a slightly different position at the start of the game, so players will enter the first round with different priorities and incentives when evaluating the starting cases and the starting judicial candidates. There was a lot of playtesting and iteration about how to incorporate these, what types of goals to have, how many goal cards to have, how much to make them worth, how many philosophies to have on each card, how to have players select their goal card, and more. So the challenge was getting this aspect of the game to fit within the larger structure, but ultimately I think the game is better for this addition.

Grant: What happens during the Adjudication Phase?

Talia: The Adjudication Phase happens at the end of each round (after each players has completed their 3 actions for the round), and this is where a number of things resolve: (1) elevate new Justices to fill vacancies on the Court, which will shift the Judicial Philosophy Tracks and potentially change which parties are currently prevailing on the various cases; (2) advance all of the Cases toward resolution and score one Case, awarding it to the player with the most clerks on the prevailing party; and (3) age the Justices to advance time and make room for new Justices.

Grant: When does the game end?

Talia: The game covers 1789 to 2010, divided into 3 eras: 1789-1865, 1866-1954, and 1955-2010. The game ends when either the Cases Deck or the Justices Deck is exhausted. This means that the game lasts up to 15 rounds because one card is revealed from the Cases Deck each round, but about half the time the game ends earlier (somewhere between 12-14 rounds) if the players are more frequently retiring Justices and going through the Justices deck more quickly.

Grant: What type of end game scoring is there?

Talia: There are 5 ways to earn Renown Points at the end of the game: Case Breadth (winning a set of cases related to each judicial philosophy), Case Depth (winning the most cases in any given judicial philosophy), Dissents (being on the defeated side of cases and using a clerk from a Justice to “write a dissent”), Bench (having the most clerks on Justices at the end of the game), and Goal (earning between zero and nine points for your Philosophy Goal Card at the end). The goal is to give players a lot of difficult and meaningful decisions to wrestle with over the course of 2 hours simulating over 200 years of history.

Grant: What has been the experience of your playtesters?

Talia: The experience has been profoundly gratifying and encouraging. Working on this game has been an enormous privilege and challenge over the years, but the playtesters and their enthusiasm is what has kept me going. I’ve gotten so many wonderful specific ideas from playtesters, but I’ve also gotten an invaluable amount of energy from playtesters.

Grant: What do you believe the design does well?

Talia: I think the design does a good job of presenting the players with many difficult and meaningful decisions with minimal downtime. I love board games that force me repeatedly to make difficult decisions (that I have a wrestle with and that make me feel like I don’t have enough actions or time to do everything I need to do) and meaningful decisions (that will quickly have a material impact on subsequent turns, the overall game state, and the outcome). I think the design puts players in the position of confronting a barrage of such decisions with limited downtime and an overall game that generally clocks in right at 2 hours for me. I also think the design layers on that a pretty comprehensive arc of history from 1789 to 2010, leaving players with a memorable narrative of the Court that they collectively empowered and of the cases that they collectively resolved. Each game creates a story of a country that might have been and hopefully inspires players to learn a bit more about this fascinating institution.

Thank you so much for your time in answering our questions Talia. I really am looking forward to this game and cannot wait to give it a go. Games on these type of subjects are always very interesting as our minds are expanded as we have a good time playing a game with friends and I look forward to learning more about the U.S. Supreme Court.

If you are interested in First Monday in October: The U.S. Supreme Court, 1798-2010, you can check the project out at the Kickstarter preview page at the following link: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/fortcircle/first-monday-in-october

The Kickstarter Campaign is scheduled to commence on Tuesday, November 19th.

-Grant

Grant, you always do a great job in these interviews. You are very thorough and always help me understand the game. This one is really fascinating. I might need to add this one to my (over) growing collection.

Thanks, as always!

Nick Stasnopolis

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks Nick. I will say that these designers are really good and filling in the gaps in my questions and even responding to things that I should have asked so it comes off as these are “good interviews”. They do the work and I appreciate their help.

LikeLike

Thanks Grant. Very informative. I won’t get much household Renown for buying yet another game, but my Philosophy is that I need the unique ones!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes. This one looks to be an ungamed subject.

LikeLike

John, my entire family laughed out loud at this! I hope you have a chance to play the game sometime and you enjoy it!

LikeLiked by 1 person