We have had a few year association with Francisco “Pako” Gradaille who is an emerging game designer and a really interesting individual. Here on the blog, we have done several interviews with him for his previous designs including Plantagenet: Cousin’s War for England, 1459-1485 from GMT Games and Cuius Regio: The Thirty Years War from GMT Games. We have also hosted a few Guest Posts where he has unveiled his thoughts on game design and how he is approaching it armed with technology and math, which are very interesting. Here are links to those posts:

Men of Iron Series from GMT Games – Variant Chit-Pull System from Francisco Gradaille

Game Design, Software Development and Math by Francisco “Paco” Gradaille

Recently, I caught wind that he had a new design coming out with Salt & Pepper Games called Onoda, which is a solitaire wargame that follows the life and interesting story of Hiroo Onoda who was a Japanese soldier that refused to believe that World War II was over and held his post on Lubang Island from 1945-1974 before he surrendered. The game is a look inside this thirty year period full of adventures, danger, comical situations and tragic moments, life and death and, above all, a demonstration of the resilience of human beings in adverse conditions. I reached out to Francisco and he was more than willing to share about the design.

If you are interested in Onoda, you can learn more about the project on the Gamefound page at the following link: https://gamefound.com/en/projects/saltandpepper/onoda

Grant: Francisco thanks for coming back to the blog. How have you felt about your published

game Plantagenet from GMT Games?

Francisco: The reception has been very good and all the people involved in the project are very happy about it. The nominations for the awards (Golden Geek and CSR) were a huge surprise, especially the CSR nomination for best game of 2023. I can’t complain at all about it, being it my first published game, and it sets a high benchmark for my next designs.

Grant: What have you learned from that experience that will make you a better designer?

Francisco: A lot of things. It is as if I had attended a master class in game design. Now I see how naïve I was in so many things, and how many mistakes I was making at the beginning. I have been able to learn from some of the greatest experts in the field. Volko Ruhnke and Christophe Correia were not only key for Plantagenet but also have been a constant source of knowledge and learning for me. Although, if I had to choose one thing I have learned it would be that I learned to not listen to the inner voice that keeps telling you that the game is already finished and, instead, try to look for new ways to improve upon it.

Grant: What is the status of one of your other ongoing games Cuius Regio?

Francisco: The game is finished (see the previous answer for a good laugh). But it’s not me who says when it is ready. It’s also the developer, Mike Sigler, and the people that are testing it. We are waiting for the art department to finish the graphic design and we are good to go.

Grant: What is your new game Onoda about?

Francisco: This should be an easy answer but it’s really not. We could say that this game is about the thirty years that Hiroo Onoda spent in Lubang doing guerrilla warfare and thinking the WWII had not ended. But that’s not the main theme of the game. That’s simply the setting. The main theme in the game is resilience in the face of adversity. How to face a very difficult situation following the Japanese philosophy of Shoganai. Which doesn’t mean to accept everything that comes to you, but to understand that you can’t control fate and the only thing that is in your hands is how you react to what happens to you. But I always have liked movies, books and games that have a strong subtext. And this game has one that I didn’t want to explain and let players just discover it on their own.

What I have found lately is that games that deal with complicated issues tend to be interpreted at face value, so I have changed my opinion and I’ve started to explain what the game is also showing you. This game explains a tragedy. A sad story for everyone involved. You can play it and see Hiroo only as a hero. But what about the people living in Lubang? What was their perspective? The game, using certain elements, aims to also show that part of the story. The events, the alarm levels that fill the island, the growing paranoia… all these elements explain another story. One that I hope the players can see after they’ve played the main one.

Grant: Why was this a subject that drew your interest?

Francisco: It explains a lot about human nature. The sometimes-misplaced sense of honor, our extraordinary ability in self-deception, resilience in front of adversity… all these elements appear in this story and were something that drew me in.

Grant: Who was Hiroo Onoda? And why should we care about his life and mission?

Francisco: Hiroo Onoda was a young soldier from the Japanese army at the end of the WWII that was sent on a mission to protect Lubang by becoming a guerrilla fighter and performing missions of sabotage. He was a strong-willed man that believed all the information that came to him from the outside was manipulated to make him surrender (which had been forbidden). So, he spent thirty years on the island thinking that WWII had not ended. I think this is an important story on two main levels. One is the main story of somebody that complied with his duty far beyond what most of us would ever do. A stoic man that was willing to give his life to defend his country and never surrender. But there is also the story of the damage a man like this can create around him. And it should make us think about how terrible wars are, for everyone involved, but most of all to the innocent civilians who are caught in the middle.

Grant: What can we learn from his example?

Francisco: From his personal example, extracting all the other parts, I believe that we can learn to not try to control our fate and instead of that to focus on what we can do at any moment to deal with what happens to us. European culture makes us grow with the sense that we have a measure of blame and control about our destiny. That luck (good or bad) is not as important as other other factors. I think Onoda just accepted what came to him and tried to deal with it as best as he could. That’s the main lesson here.

Grant: What is your design goal with the game?

Francisco: Apart from the story and theme, I wanted to create a solitaire game that felt and played more like an adventure than a puzzle to solve. I tried to make a fast game, that rewarded mastery of the process but also that forced players to deal with and to accept what luck might bring them.

Grant: What sources did you consult about the details of the history? What one must read source would you recommend?

Francisco: My first source, that is not reliable at all, was Werner Herzog’s The Twilight World. It was very useful to get the poetic mood of the game. But it’s all about the heroic side of Hiroo. Then I used Onoda’s autobiography called Never Surrender: My Thirty-Year War as the main source for events and missions which he undertook. All of them are taken from that book. Finally, I collected some old newspapers from the Philippines and the US to try to get some perspective on what people of the time thought about Hiroo. And to get the data of the damage that the locals of Lubang suffered.

Grant: What other games did you draw inspiration from?

Francisco: Not a direct inspiration, but I had in mind all the old games about hexagon exploration that were so popular in the 80’s. I wanted players to feel they were in unknown territory with almost every action they took. So games like Source of the Nile were a source of inspiration, although the mechanics were not taken from anywhere else.

Grant: What has been your most challenging design obstacle to overcome with the game? How did you solve the problem?

Francisco: I didn’t want the game to become a puzzle or a luck fest. So, walking that line was kind of difficult. How to add a lot of luck-dependent elements but, at the same time, give an amount of control to the players about it? How to not give so much control that you can start counting cards to see if you can win or not? I tried some mechanics and the chosen ones referred to manage the random generators of the game, mainly the counters that you use for tests, so that players have enough information to know how risky it is to take an action. I think that turned out quite well.

Grant: What is the goal of the game?

Francisco: To survive for 30 years in Lubang without succumbing to paranoia in the process. Players should be also completing missions that Onoda thought he had to do to accomplish his duty as a Japanese soldier. A mix of survival and mission solving ends up telling if Onoda was just a guerrilla fighter or he was more than that.

Grant: What is the general Sequence of Play?

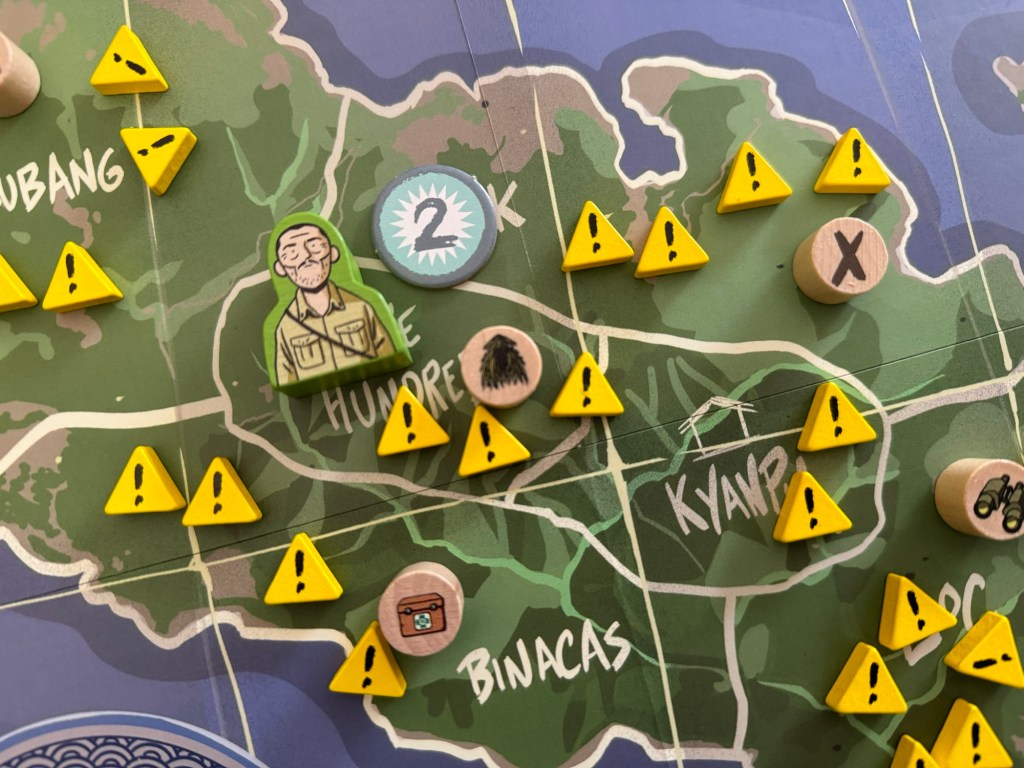

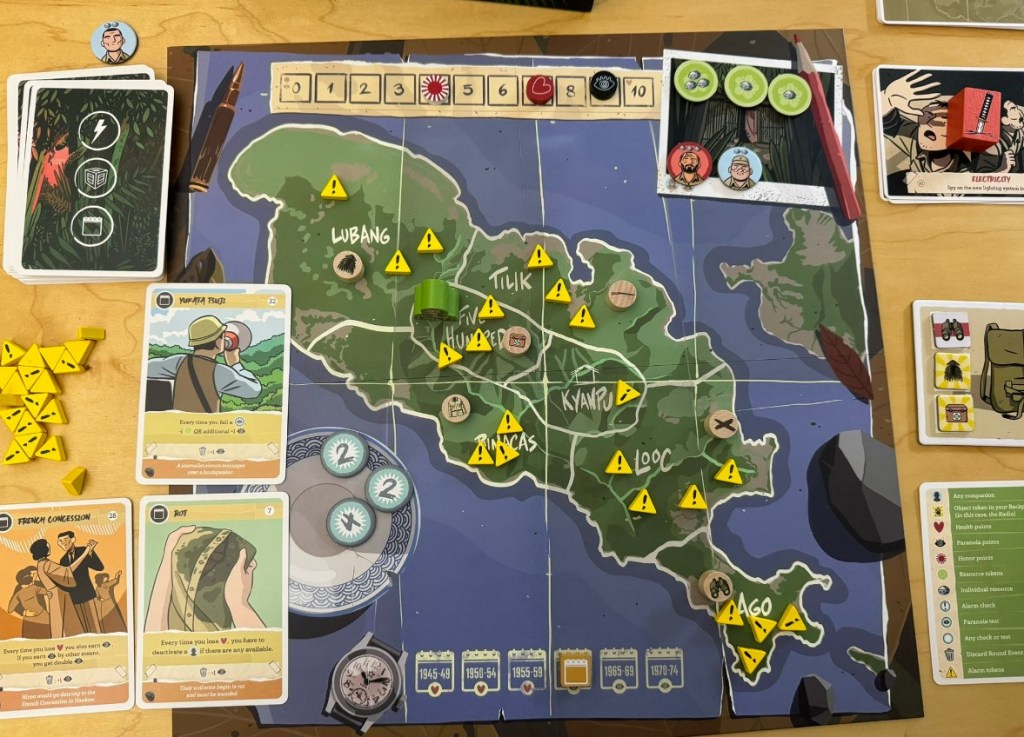

Francisco: Each 5 years is made into a round. A round has no fixed duration. Players can take actions with Onoda until they feel it’s too risky. They can pillage to get resources, they can do the mission of the round, move from one place to another one or try to repair their equipment. As they take actions, Alarm Levels keep increasing on the island in the spaces where these actions are taken and events (usually negative) happen. After they have done everything they can, they return to their camp and end the round only to start a new one.

Grant: What do the concepts of Alarm Levels, Alarm Checks and Paranoia Checks play in the

game?

Francisco: Alarm Levels represent the reaction of the islanders to Hiroo’s actions. The more he acts, the more alert they are and the more dangerous it becomes for Onoda. Any time he has to perform an action he must succeed at an Alarm Check that goes against the level of alarm in a certain region. So, each action he takes in a region increases the difficulty of the next one in the same area.

Paranoia checks represent the declining mental health of anybody that spends 30 years fighting in the jungle. There are certain events and situation that can trigger a Paranoia Check against the current level of Paranoia of Onoda. If he fails, the game ends. And it doesn’t end well.

Grant: How do players resolve these tests?

Francisco: There are no dice in Onoda. They draw a counter from a draw bag (provided with the game) and check for one of the sides. On one side there is a number, like if it was a dice, and compare it to the current level of Alarm or Paranoia. If the number is higher, the test succeeds.

Grant: How is the game lost?

Francisco: If Onoda loses all his health or reaches a high enough level of Paranoia, the game ends. There is also the possibility of losing due to a failed Paranoia Test. When Health levels and Paranoia cross (they start from opposite sides of a track), any movement of any of the two triggers a new Paranoia test.

Grant: What is the makeup of the draw bag? How did you use math to make the distribution

of results?

Francisco: I’m a mathematician, so I created a distribution of numbers that allowed me to calculate the exact difficulty I wanted Onoda to have. There are 12 counters that act as a 6-sided dice. Two counters for each number. But there is only one 6 and there is one 0.

These counters are double sided. They act as the dice but also as the resources. On the other side there is the number of resources (food) that Onoda gets. And the number of resources is paired with the number of the dice. The higher the number, the higher the number of resources. So, when a player has enough resources for the round, there is usually only bad “rolls” left in the bag. But when a player has just a few resources, the good numbers still remain there and it’s less risky to take actions. This combination balances the game a bit and creates some very interesting decisions by the players.

Grant: What is the layout of the board?

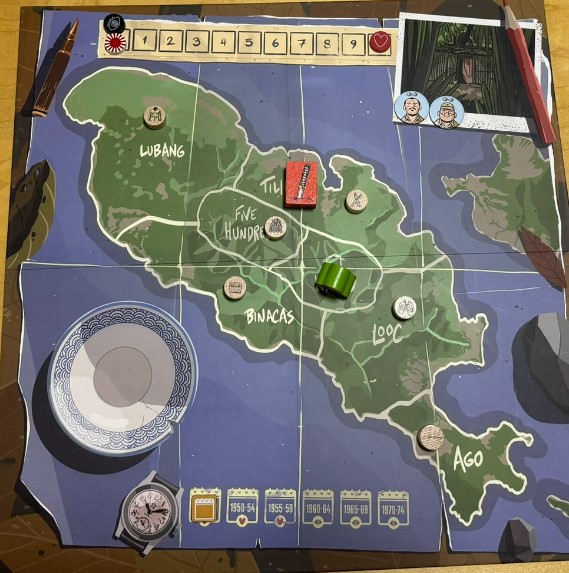

Francisco: The board is a a map of Lubang with its seven regions identified including Lubang, Tilik, Five Hundred, Binacas, Looc, Ago and Kyanpu. The tracks on the board are for Health, Paranoia and Mission Points. There is Onoda’s camp in the upper right corner, which is a place to set some pieces like your companions and gathered resources. And also, a place to leave your counters until the action ends (a rice bowl).

Grant: How does the design utilize cards? What types of different cards are included?

Francisco: There are the Mission Cards, that explain the mission and the consequences of success and failure. There are also the Event Cards. There are 3 different types of Event Cards:

Round Cards that usually have a negative effect and remain active for the rest of the round. These will typically do things such as hindering movement, supply collection or other actions.

Instantaneous Cards that have a direct and immediate effect. They may be good or bad and can involve the use of an asset or a check.

Reserve Cards which are good effects cards that can be kept in the player’s hand and used to retake a failed Check or for the effect that the card shows. There is a limit to these number of cards that players can have though and is constrained by the number of healthy companions you have at the time +1. This typically means a limit of 2-3 of these Reserve Cards.

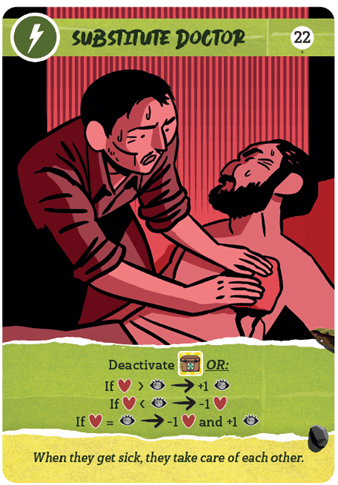

Grant: Can we see an example of an Event Card and a Mission Card?

Francisco: This is an example of an Event Card called Substitute Doctor (Card #22). You will notice the lightning symbol in the upper left hand corner of the card which means this is an immediate effect event. In this Event, we talk about what happened when one of the companions got sick. They had to become makeshift doctors and nurses for as long as it took for their companion to recover their strength. The effect of the card is immediate. They must deactivate the Medicine asset if they have it available but if they are not able to do it, they suffer an effect according to the level of Health and Paranoia as compared with each other on the track on the board. As you can see, these kind of events tend to affect the mental and physical health of Hiroo and can even trigger an abrupt end to the game by causing the player to have to take a Paranoia Check.

Here is an example of a Mission Card. At the bottom we can see where the mission takes place (Looc) and a small description of what the mission is. This was an effort to take food needed to survive but also to make a map of the village. On the right side you see what Onoda must do to succeed: namely an Alarm Check plus deactivating a companion. If he succeeds, he will get an Honor Point and one random Resource Marker drawn from the draw bag and he will recover his companion as well, even the one that was just deactivated to complete the mission. If he fails, he’ll lose one Health, add one extra Alarm Level to Looc and deactivate another companion (potentially causing the death of one of them).

Grant: How does the player feed themselves and his companions?

Francisco: Using the Pillage Action, Onoda gets resources that basically represent rice that he steals from the islanders. At the end of a Round, Onoda must use two units of resources for him and two for each active companion (in full health) or 3 if they are deactivated (ill, hurt, etc.). It can go from 2 if all his companions are dead to 11 if Kozuka, Shimada and Akatsu are all deactivated. If there are enough points, and ending early can be a voluntary decision by the player, Onoda loses one health point for each missing resource.

Grant: Are Onoda’s companions there to help him or do they hinder his mission?

Francisco: In a way they help him, allowing him to fulfil certain Missions and to succeed in certain events. If they are active, they allow the player to hold an extra Reserve Card in hand.

But, at the same time, they need to be fed. So, it creates the necessity of taking more actions to get the resources needed to survive.

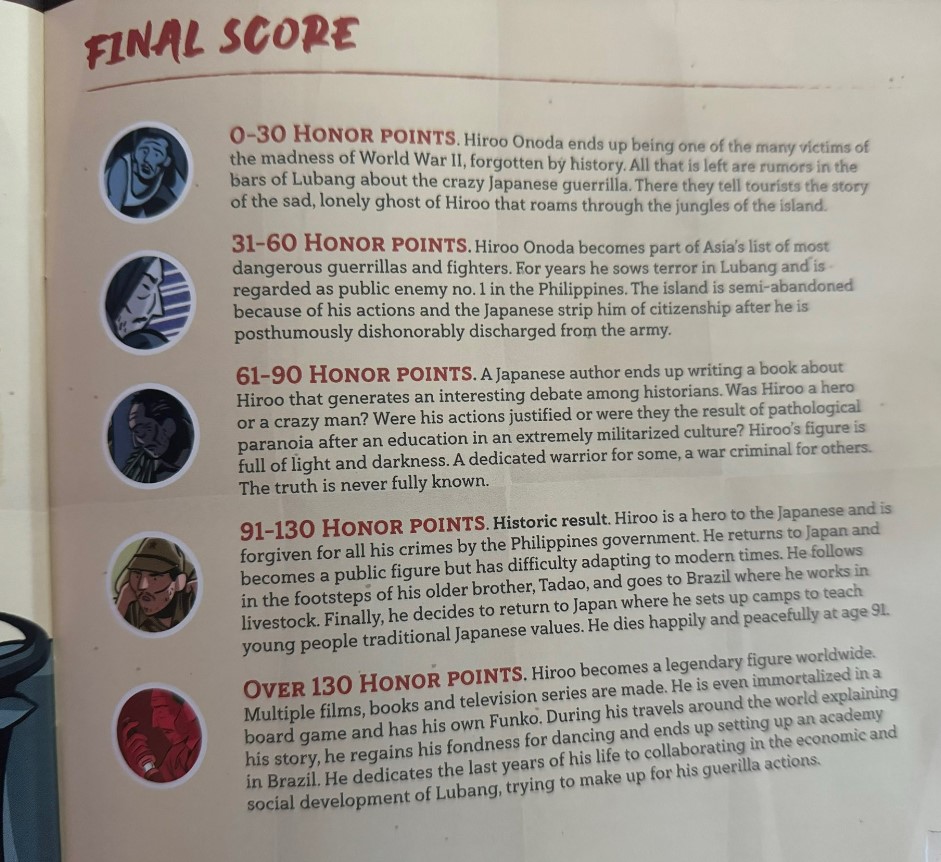

Grant: How are Honor Points and then Victory Points scored?

Francisco: Honor Points are Hiroo’s interpretation of what his Missions are. He believes that completing the Missions is what the Japanese army asks of him and that it earns him honor. When he succeeds at a Mission, the reward always includes an Honor Point.

Victory Points are scored at the end of the game and depend on a number of factors: how many Honor Points are there, how many companions are active, how many assets are active and how far has Onoda descended into the depths of Paranoia and how healthy he is. They can be from negative to more than 130, and they can lead to different endings for Hiroo. From being considered just another terrorist in his story or to being appreciated all around the world.

Grant: What general strategies do players need to keep in mind?

Francisco: They must learn how to properly manage the Reserve Cards, which are one of the keys to controlling the randomness. They also need to understand that when there are a lot of resources in Hiroo’s bag, the counters that are still in the bag are usually bad. So, risks should be taken when the island has not been ravaged but they should be avoided when there are high Alarm Levels and many resources available.

I would recommend players embrace the story the game tells and try to journey with Onoda and his companions through the hazards. Maybe focus more on creating an interesting story than in actual winning. But there’s also a game there for the hardcore competition lovers. Knowing how to calculate the odds of the draw bag and trying to manage it in you favor is not easy.

Grant: How does the art and graphic design efforts of Javi de Castro and João Duarte-Silva help in building the thematic experience of the game?

Francisco: Javi de Castro has conveyed the right tone to the game. It has gone beyond what I expected. How he tells us if an action is epic or it’s just a sad thing with the simple (spoiler: they are not so simple), clean lines and color palette is amazing. I had that tone in my mind when I was designing the game, but he made it into a reality. If anybody likes the style of Onoda, please go and get some of Javi’s comic books. They are really, really good.

João is a master of graphic design and has improved not only the ergonomics of the game but also how it provides the information to the players. This last part is really important because a well graphically designed game can reduce the cognitive load for a player and let them focus on having fun. It allows a player to “see” and understand what’s on the board or on the cards faster and better.

If you find Onoda is any good, it’s in a great part thanks to both of them.

Grant: What type of experience does the game create for players?

Francisco: I have said so before, but it’s a dual experience. On the surface, it is a game about survival, endurance, reacting to fate and taking risks. On a deeper level, it is a game about the consequences of your actions, how war damages us all and how a story that seems epic as seen from one side is a tragedy when seen from the other.

Grant: What are you most pleased about with the design?

Francisco: I’m very happy with tester’s reactions to the game. I’m happy that it triggered an interest in Onoda’s story and that it gave them an experience of excitement and tension. I’m also happy that some of them have seen the story below the surface and have told me so. That was what I was more unsure of as a designer: if I’d be able to make this subtext subtle enough but at the same time not too obscure.

I want to add a disclaimer: if any player has not seen that subtext and finds it hard to get it from the game as it is, it’s not their fault. It’s very probable that it’s because I have to learn much yet as a designer and improve my craft, which I’ll keep doing.

Grant: What other designs are you currently working on?

Francisco: The same as a lot of other designers, I’m always in the middle of multiple projects at the same time. There are three main ones now: One historical, also solitaire, which I hope to be able to show in a short time with a Spanish publisher. Another one that is a political and influence game about the election of the Pope which has been just acquired by another Spanish publisher and it’s having the best reviews that any of my games has ever had. And finally, Cuius Regio from GMT Games, that me and Mike keep taking care of and tinkering with although almost all our real work is already completed.

Thank you for your time in answering these questions Francisco. I have played the game extensively and have really enjoyed the experience. I have very much enjoyed the learning process with the game and the management of risks and find that I am thinking a lot during the game, not just about the mechanics, but also about the story itself and what his life meant and what can be learned. I have a playthrough and a review video upcoming that will be a part of the campaign. Good luck!

If you are interested in Onoda, you can learn more about the project on the Gamefound page at the following link: https://gamefound.com/en/projects/saltandpepper/onoda

The Gamefound campaign is set to start as of Thursday, November 7th at 11:00am EST.

-Grant