Several months ago, I came across a new game while perusing the VUCA Simulations website that is designed by Brian Asklev. He is a pretty sharp designer as he worked with us on a series of Event Cards Spoilers for another of his upcoming games called Baltic Empires: The Northern Wars of 1558-1721 from GMT Games. His new game is a Napoleonics game called 1812 – Napoleon’s Fateful March. The cover art is amazing, the topic looks great and the approach that he is taking seems to be very novel. I have been pretty keen on this design since seeing it last year and actually added it to my Most Anticipated Wargames of 2024! post. I reached out to Brian to get the scoop on the game and he was more than willing to share.

Grant: What is the historical setting of your upcoming game 1812 – Napoleon’s Fateful March from VUCA Simulations?

Brian: Well, as the name suggests it’s a game that focuses on Napoleon´s 1812 campaign into Russia. The game covers events from the start of the campaign in June 1812, to the march on Moscow and then the subsequent retreat back from Moscow and ends roughly at the point when the French army (or rather the pitifully small remnants of the French army) reached its starting positions in early December 1812.

Grant: Why was this a game that you wanted to design?

Brian: I have been fascinated with Napoleon’s 1812 campaign for years, as it is a highpoint of drama and tragedy found in modern military history. Kevin Zucker´s game Highway to the Kremlin: Napoleon’s March on Moscow from the Operational Studies Group (OSG), an entry in his Campaigns Series, really opened my eyes to the logistical aspects of Napoleonic Era campaigns and how that could become a central part and focus of a game instead of abstracted as in most other wargames on the matter.

This sowed in my mind the idea of a simpler and faster game on the topic with the same overall focus on how an army could be weakened and even destroyed by factors such as weather and starvation. And also, how this attrition, and not the battles, could be one of the decisive factors in a military campaign. As the Russian campaign of 1812 is the epitome of such a campaign, I decided to start with that.

Grant: How did you get connected with VUCA Simulations?

Brian: I sent them an email with a short description of the game and simply asked if they were interested, which they turned out to be. It was almost too easy! 😊

Grant: What is your overall design goal with the game?

Brian: I wanted to make a game that had logistics and planning at the forefront. But in contrast to Zucker´s Campaigns Series, I wanted one that was fast and easy to learn, relatively fast to play and with lots of tension and little downtime. So my goal was merging logistics, planning and fun. Something that luckily proved to be much easier to do than it sounds.

Grant: What is the game’s scale? Force structure of units?

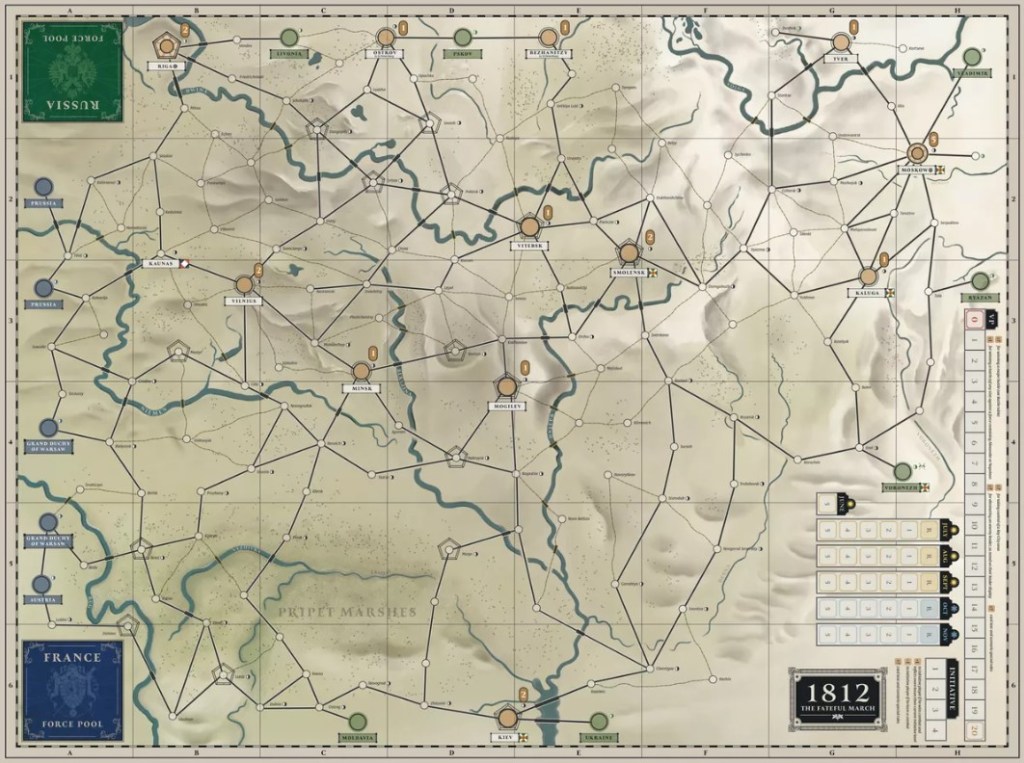

Brian: The game uses generic Strength Points (SP’s) that roughly represent divisional units of infantry of 10,000 men each or cavalry divisions of 5,000 men each. The map is a point-to-point map with the distance between points being roughly 70 km.

Grant: How does the design use cards and what is the anatomy of the cards?

Brian: Cards in 1812 are dual purpose. They have an Orders Value (the upper right number in the scroll) and an Event. Cards can be played for either one or the other. Each turn, players may place a few orders for free and can increase this number by playing a card for extra orders. Cards may also be played for their Event. Each card lists specifically when and how that card may be played for its Event. Battle Event Cards are marked by a crossed sabers icon, and list if there are any conditions that must be fulfilled for it to be played in battle.

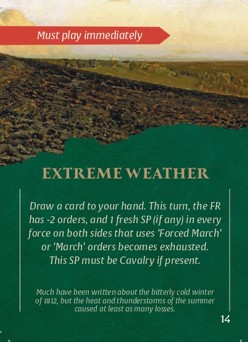

Each deck also have a number of “Must Play Immediately” Cards in their decks. Whenever such a card is drawn it is immediately played for its Event (which is often bad for the drawing player). These events allow the game to handle occurrences outside the control of each side´s leadership and avoids some of the “god-like” effects seen in other CDG’s where players determine when bad weather or disease strikes.

Players draw 3 cards at the start of each turn, and then 1 at the start of each of the 5 turns within a month. Compared to CDG classics like Paths of Glory this gives players a much smaller hand at all times and makes it harder to micromanage which cards will be played, and when, throughout a month. This both handily represents the problems of coordination and planning in the real world and helps reduce analysis paralysis as your choices are fewer. An added benefit as compared to the classic CDG’s is that players won’t run out of cards near the end of the month as easily and the tension of drawing a “Must Play Immediately” is present at all times. It also reinforces the narrative feel of the game that opportunities and problems come and go throughout the month instead of being concentrated at the start of it.

As in all CDG’s some Events are better, or more important, than others. To help balance this and allow an element of scripting, players are allowed to pick one of their cards each month instead of drawing it randomly. The player aid card includes a list of 2 cards per player per month. Players may (but do not have to) choose to pick one of those two automatically as part of their 3 new cards at the start of the month.

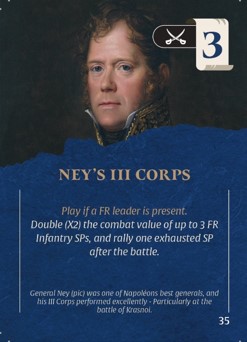

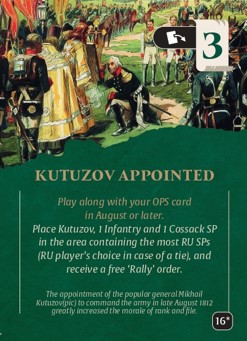

Grant: Can we see a few examples of the cards and can you please explain their use?

Brian: Here are a few examples of cards:

“Ney´s III Corps” is an example of a French (denoted by the blue color of the card) Battle Event Card (identified by the crossed sabers icon in the upper right hand corner of the card). This type of card often has a condition that must be fulfilled before the event can be played. In this case, there must be a French Leader present to play the card. This card provides a doubling of the combat value of up to French infantry SP’s. Then after the battle, the player may rally one of its exhausted SP’s for free.

“Extreme Weather” is an example of a Russian (denoted by the green color of the card) Must-play-immediately Event Card. The Must-play-immediately reminder is denoted by the presence of the red banner at the top of the card. As mentioned above, these cards are automatically played immediately upon being drawn and usually effect either one or both players in a negative way such as loss of strength points, loss of orders, etc. This card happens to have effects for both of the players but first the French player will gain -2 orders this turn and then 1 fresh SP in every force on both sides that uses Forced March or March during the turn must become exhausted. This card mimics the negative effect of the harsh Russian winters on the combatants but more so on the French as the Russians are used to this extreme weather.

“Kutuzov Appointed” is an example of a normal Russian Event Card. These clearly list exactly when the Event Card can be played. In this case, the Event is played along with the card you chose to play to increase your number of orders. The card cannot be played until August 1812 or later. The benefit is that the Russian player gets to place the Kutuzov Leader on the board with 1 Infantry and 1 Cossack SP in the area with the most Russian SP’s. The card also provides a free Rally order.

As mentioned above, some cards can be automatically selected in specific months instead of being drawn randomly. These cards are listed in a table on the player aid and to make it faster to find these cards when searching through the deck all cards listed on that table have their card number (lower right hand corner) in a black box.

Grant: I also see where the game uses secret order placement. What does this mean and how does this mechanic work?

Brian: The game uses wooden blocks with stickers on one side for orders. When players put these on the map only the owning player can see the identity of the order while the opponent can only see that some kind of order was placed in the area. As each player has 4 dummy order blocks that they can use to deceive the opponent and because of that players are always kept in uncertainty about the intentions of their opponent.

Grant: Why was it important to include such secret order placement?

Brian: Two reasons for the inclusion of this mechanic. First of all, no serious wargame should give players full knowledge of enemy strengths and intentions as the fog of war elements has been a critical factor throughout military history. Good commanders were those who were able to anticipate their enemy’s moves while using feints and deception of their own to keep the enemy in the dark about their own operations until it was too late to react. Secondly it is just plain fun and incredibly tense to play games with such mechanisms! 😊

Grant: What different orders do players have access to and how are they resolved?

Brian: Quite a lot actually. Besides having different effects their resolution is also timed, so the following list is both a list of the orders in the game and the order in which they are resolved.

- Forced March, which allows fast movement but with reduced combat effectiveness.

- Cavalry Patrols, which allows stacks with Cavalry/Cossacks to reveal the identity of enemy order blocks and the content of enemy stacks in an adjacent area.

- March, which is a standard move.

- Evade, which allows you to move out of an area if enemy forces entered it.

- Defend, which reduce the losses suffered in battle if defending (all battles are resolved at this point in the sequence).

- Rally, which allows you to flip exhausted SP’s back to their fresh side.

- Cossack Raids, which allow stacks with Cossacks to eliminate an adjacent exhausted enemy SP as well as remove any Forage orders that might be there.

- Place Depot, which allows you to branch out your chain of depots.

- Forage, which reduce the losses suffered from Attrition, which is checked across the board at this point in the sequence.

Grant: What role do the Leader screens play in the game?

Brian: The leader screens have 2 purposes. They make it easier to conceal the number, type and fresh/exhaustion status of the SP’s a leader have under him, while also containing a handy summary of that leaders special rules and abilities. Players may not check the content of enemy stacks but can only see the top unit, but by having the screens it is easier for the owning player to keep track of his own army as you can sort the SP’s by type and state behind them.

Grant: What type of focus does the design put on logistic planning?

Brian: In most wars throughout history losses from disease, starvation, fatigue and desertion have dwarfed losses from enemy actions. When playing 1812 (and future games in the Marshals and Quartermasters Series) players are always, just like their historical counterparts, planning their operations in a way that will create a situation where the enemy army finds itself in an untenable situation. You can lose most of your army in this game without fighting a single battle.

Grant: How do you model march attrition?

Brian: During the “Check Attrition” step of a turn, players check each of their stacks across the map to see how many losses they suffer from attrition be referencing a table. Attrition losses depend on 2 factors: The number of SP’s in the area (both fresh and exhausted) and the distance to the nearest friendly depot. This simple mechanic creates a situation where players, just like their historical counterparts, find themselves spreading out their armies to better allow them to live off the land and only concentrating their forces in anticipation of a battle. A lot of cards also cause extra losses from attrition if certain conditions are met – These conditions usually involve forced marching.

Grant: How do players go about securing supply and what is the role of Depot markers?

Brian: Supply is traced from your supply source to a nearby depot and from there to another nearby depot to form a line of connected depots. Players use the Place Depot order to expand their network of depots, but each player only have one such order to place each turn so players will find it hard to sustain offensive thrusts in multiple directions at once.

Grant: How are the Devastation markers used?

Brian: Devastation markers are used as a modifier on the attrition table. Devastation is placed in areas where battles take place as well as areas where one side resolved an evade order (to represent the scorched earth strategy of 1812). In addition to this, devastation is placed according to event text and one a lot of results on the Attrition table itself. Devastation markers are always placed at the bottom of each stack so for ease of play we made them color-coded according to Devastation Level (from 1 to 3) and round as well as slightly larger than the SP counters so players can easily see which areas of the map are devastated.

Grant: What area of Russia does the board cover?

Brian: The map roughly covers the area cornered by Königsberg, Tver, Moscow Voronezh, Kiev and the Austrian border. It thus covers the entire 1812 theatre of war.

Grant: Why was point-to-point movement the best option here?

Brian: Since armies in this period were deeply tied to the road net point-to-point just felt right. An added bonus to a point-to-point map is that it is easier to design a map and give the designer a way of preventing weird gamey maneuvers that would never have happened in real life. 😊

Grant: How are the off-map areas used?

Brian: Off-map areas represent the regions beyond the map. In game terms they are simply areas that can only be used by the owning side.

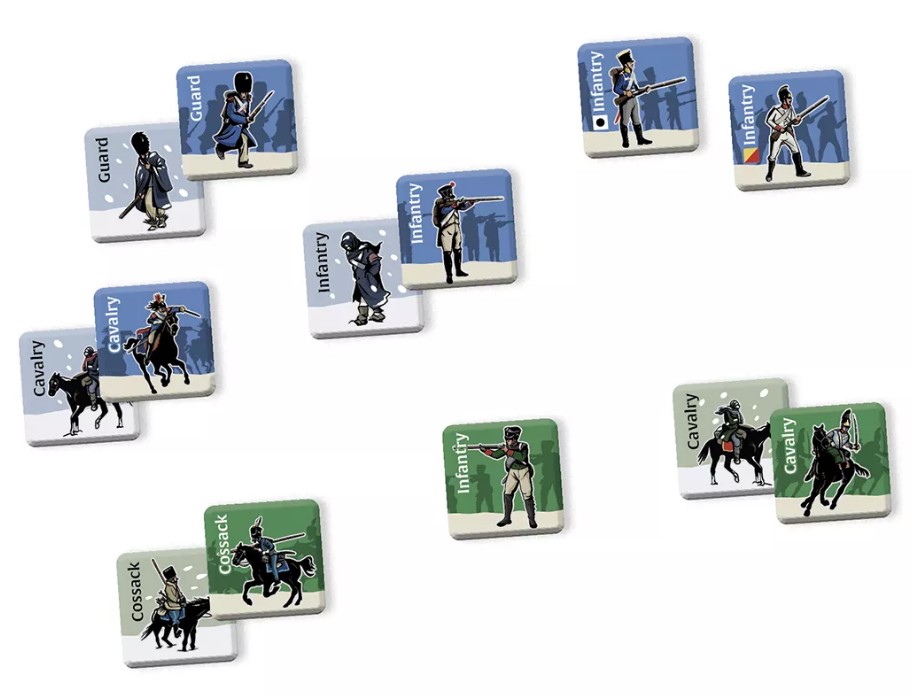

Grant: What is the anatomy of the counters?

Brian: The counters are very simple and only contain the unit type and the number of strength points (if more than 1). This represents the fact that at this scale and with the focus on planning and logistics all units are more or less the same and the only thing that counts is the number of muskets/sabers they can effectively bring to bear in battle and how many mouths there is to feed.

This simplicity had the added bonus of leaving lots of space on the counters for pretty and evocative artwork and Wouter Schoutteten, the graphics artist, really nailed the focus of the design and the historical topic with his graphics for the counters with their fresh frontside and exhausted backside.

Grant: What different type of units are available to both sides?

Brian: Both sides field infantry and cavalry. In addition to this, the French have their Imperial Guard while the Russians have Cossacks. As Napoleons forces also included contingents from his (not too enthusiastic) allies of Prussia and Austria these are also included as a separate SP type while Napoleons many other allied contingents from various European minor states and non-French parts of the empire are treated as French for simplicity.

Cavalry and Cossacks move faster than infantry but fight less effectively in fortress terrain while Imperial Guard fights better than regular infantry, and Cossack fight very badly. Cavalry and (especially) Cossacks are also hugely important when evading from contact or conducting pursuit after battle but other than this the SP’s function more or less the same unless a card is played that affect a specific type of SP in some way (there are lots of these however so the game doesn’t feel as dry and flavorless as I might make it sound).

Grant: In general how does each sides forces compare?

Brian: In terms of overall strength both sides are more or less equal in strength, but the Russians start out far more dispersed than the French. The French have their Imperial Guards and overall better cards to play in battles, while the Russians have their Cossacks which fight with a battle strength of 0 but can raid exhausted French SP’s and negate their Forage orders, as well as being twice as good as normal Cavalry in a screening/pursuing role.

Grant: How does combat work in the design?

Brian: Combat is in essence super simple: Each player counts their number of fresh SP’s present and add/subtract the result of their Battle die. This total is then referenced on a table to see how many losses are inflicted on the enemy. Losses are taken as a mixture of eliminations and exhausting fresh SP’s. The winner then checks to see if he is able to conduct pursuit after battle and inflict more eliminations. This is based on the number of fresh Cavalry and Cossack SP’s both sides have left after the battle. Both players may play between 1 to 4 Battle Event Cards (depending on the presence, and quality of leaders) and these cards may affect the battle results in some way.

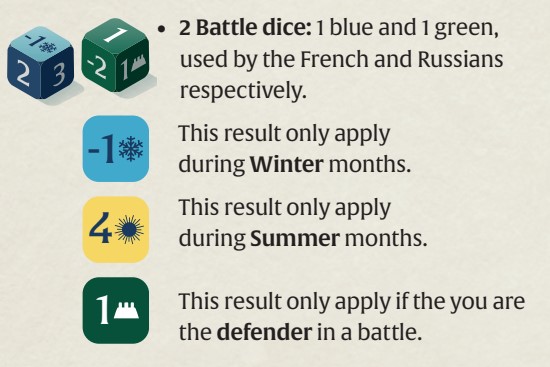

Grant: What is the makeup of the custom battle dice?

Brian: Each side have their own battle die. The results range from -2 to +4. The outcomes on each side´s die are not identical and are not evenly distributed and some of the results are conditioned on factors such as the season (winter/summer) or if you are attacking/defending.

Grant: How is victory obtained?

Brian: The player with the most victory points (VP’s) is the winner at the end of the game. For all scenarios and the campaign, the starting VP’s have been tweaked to create a balanced game. VP’s are won by capturing key cities, which have a VP value listed on the map (with Moscow being by far the most valuable), and by being adjacent to the enemy’s off-map areas at the end of the game. In addition to this, the French also earn VP’s at the end of each turn they control Moscow to represent the pressure on the Tsar to make peace.

VP’s are also won by winning battles, and the VP award for this depends on the number of eliminated SP’s on the losing side as well as for eliminating enemy leaders.

In the campaign and scenarios that cover the end of the covered period, the Russians also earn VP’s depending on the number of French SP’s eliminated during the game (eliminated French SP’s are placed in a special “French Casualties” box on the map).

For the campaign game, this all adds up to a situation where the French must earn lots of VP’s to off-set the Russian starting advantage. If they can crush the Russian armies in a series of large battles this will likely be enough to win but failing that they must keep advancing and get as many VP’s for holding Moscow as possible before the weather and increasing Russian strength make staying in Moscow too risky. At this point the goal becomes to get the army to safety and thus minimize the Russian VP gains for French losses.

Grant: What are some general strategies for each of the sides?

Brian: In the early phase of the campaign game, the Russian player will see his forces spread out while the French juggernaut is concentrated at the border and ready to deal a killing blow. So while the French are chasing the opportunity to end the war in a single blow by crushing the Russian army the Russians must fall back in a way that forces to French to advance cautiously so they don’t simply run into Moscow unscathed and in record time.

The situation on the flanks present a very different situation. The further the French advance towards Moscow the longer, and more vulnerable, their flanks become. And while the French are clearly the driving player on the Moscow axis for most of the game, the Russians have the initiative on the flanks – especially if they can strengthen their forces here. Russian success on either flank has the potential of cutting the French lines of communications and thus bringing total destruction to their main army on the Moscow axis.

Grant: What do you feel the design excels at?

Brian: The simplicity of the rules allows players to focus on fighting the enemy by trying to outsmart the opponent with their hidden orders to create situations where their supply situation worsens while theirs improves, instead of fighting the rules.

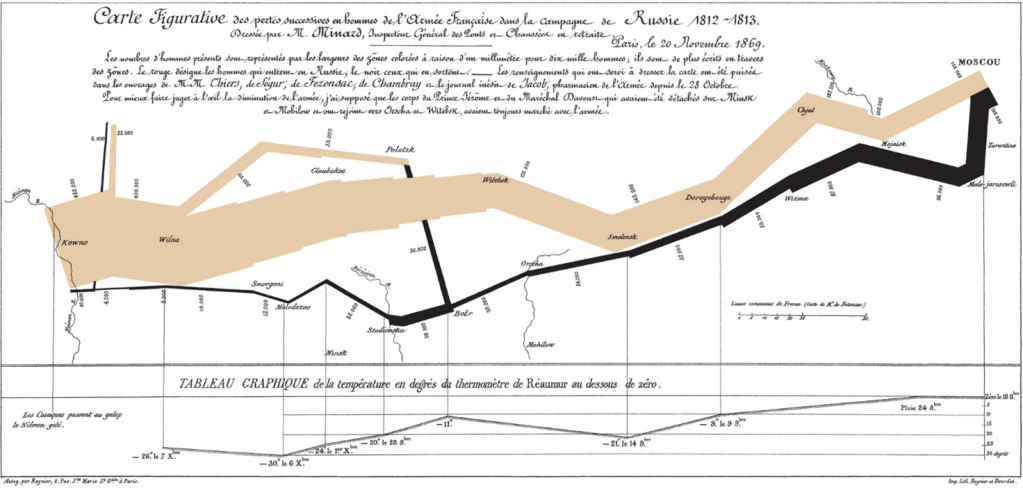

When playing 1812, and especially if playing the full campaign game, players really feel the tension and pain of seeing their army disintegrate before their eyes. In many ways it feels like reliving Charles Minard´s classic statistical graphic on the 1812 campaign. (readers unfamiliar with this should go and check it out – it is an amazing work of infographics). Writing this I realize that the prospect of a chance to “relive a graph” sounds terribly dry, but I promise you that is it actually not!

Grant: What other designs are you currently working on?

Brian: As I am optimistically anticipating 1812 to become a hit, I am already deep into designing a sequel in the series covering the 1813 campaigns in Germany. On top of this, one of the playtesters for 1812 liked the system enough for him to ask me to co-design a game on the 1814 campaign in France with him.

I am also putting the finishing touches on Baltic Empires from GMT Games and can’t wait to reveal the final artwork for that one as it has totally blown me away.

One of the Baltic Empires playtesters has also asked me to join him in designing a game using somewhat related mechanism to Baltic Empires but covering the 1725-1795 period in South-Eastern Europe. This design is also making great progress and if GMT likes it (they haven´t actually seen it yet) we hope to get this on the P500 before Baltic Empires is ready to ship.

I am also co-designing 2 games with Fred Serval (of A Gest of Robin Hood and Red Flag over Paris fame). One for Shakos called Napoleon 1870 on using the same system as their excellent Napoleon 1806, Napoleon 1807 and Napoleon 1815 games (covering another emperor Napoleon and the 1870 Franco-Prussian war). The other Fred & Brian corporation project is one that will become a new game series but this one is still secret 😉.

More info on the 1870 game will become available from Shakos Games soon as they are about to start work on the graphics soon. On top of these I also have a long line of designs with Academy Games: 3 games in their Birth of Series: 1965: Vietnam, 1618: Tragedy and 218 BC: Hannibal. The latter is a co-design with the excellent Spanish designer Jose Rivero. Academy Games are finishing the final touches on the graphics for 1965:Vietnam at this moment and I hope to see it published before the end of the year.

I also have a number of designs ready in their Fog of War Series. The most prominent one is on the Korean War called When Whales Fight. This game (including graphics) has been finished for years so I hope 2024 will be the year Academy Games pushes this out the door as well.

As the above list indicates I hope this is not my last interview with the Players Aid as I have a lot on my desk! 😊

If you are interested in 1812 – Napoleon’s Fateful March, you can pre-order a copy for $80.00 from the VUCA Simulations website at the following link: https://vucasims.com/products/1812-napoleons-fateful-march

-Grant