We have been doing this thing now for 8 years and playing wargames for nearly 10 years. So, I want to say this so that you can take what I am about to write with a grain of salt. I was not exposed to hex and counter wargames when I was younger. As a child of the 70’s and 80’s, I was more influenced by the Gamemaster Series of strategy wargames from Milton Bradley including Axis & Allies, Conquest of the Empire, Shogun and Fortress America than I was The Russian Campaign, Advanced Squad Leader or other classic wargames. Because of this, my experience in the genre is new and I started out with jumping into the deep end of the pool when Alexander and I started playing with games like Empire of the Sun, Wilderness War and Labyrinth all from GMT Games.

But the subject of introductory-level wargames has been a topic that has garnered lots of debate over the years including asking such questions as to whether they are needed, are too easy and water down the genre or don’t really attract the type of gamers that will stick with the hobby. And these are fair questions but I do love introductory-level wargames for a few reasons but also have some issues with them. Introductory-level wargames mainly serve as a gateway into more deep and challenging historical conflict simulations, offering beginners a foundational understanding of basic military tactics and command decisions. These games often provide simplified rulesets and intuitive interfaces, allowing players to grasp fundamental concepts such as troop movement, resource management and combat resolution. Through a manageable level of complexity, introductory-level wargames strike out to create a balance between accessibility and depth that will be approachable to new wargamers while also fostering a learning curve that gets them involved and builds a level of understanding while still offering at least interesting and plausible depth for seasoned grognards.

I have recently read an old letter from Richard Berg that appeared in a wargame magazine (I cannot seem to find which one) where he really criticized the introductory-level wargame. I will share that letter with you so you can get where I am coming from a bit when I write this piece.

“…publishers have had little success with introductory-level games. I think one of the answers (if “answer” is the right word) is that the level of difficulty is not the sole factor in getting someone interested in wargaming. Let’s face it, this is an elitist hobby, appealing to people with specialized interest together with the intellectual capacity necessary to master unusual systems and language. We also live in a country where a sizeable portion of the school-level population truly believes that history, in and of itself, is of no value to their lives. While that may be their problem (and it will be, unfortunately), it is something the industry must come to grips with. T’aint gonna be easy.”

I think that he has some good points but also some that miss the mark. I think that introductory-level wargames are not going to ever replace our more deep and detailed conflict simulations but are intended to reach a more broad audience than just the rabid history enthusiast who wants to see if he can do better than Rommel in North Africa or if Monty can beat Patton to Salerno. In this edition of The Love/Hate Relationship, I will take a look at what I love about introductory-level wargames and also what I hate!

Love

I always enjoy the overall approachability of introductory-level wargames. Typically the rules are fairly standard and the basic wargaming concepts of supply, zones of control, movement and terrain are all modeled well. This basic format creates a formula that new players can feel comfortable with and carry from game to game. I have played some really interesting and engaging introductory-level wargames. Here I will share a few of those experiences with you as I make some more points.

One of the first introductory-level wargames that I really enjoyed was Hundred Days 20 by Victory Point Games. Hundred Days 20 is an introductory-level Napoleonic Wargame that utilizes the Napoleonic 20 System (commonly referred to as Nappy 20), an innovative, quick playing small format wargaming system designed by Joseph Miranda. The hallmark of the system is low unit density (less than 20 counters on the map), medium weight complexity and fast playing turns with some twists. The system provides for interesting operational level maneuvers that set up dramatic battles and cavalry engagements. The system also includes random event cards and night game turns, which provides some additional obstacles to deal with that simulate conditions that affected both sides greatly during the historical campaign. This brings up one of the points that I love about introductory-level wargames, namely low counter density. The game is named for its less than 20 counters on the map and really does a great job with just those few counters. But, low counter density is a good thing in an introductory-level wargame as it really allows the players to focus not so much on balancing their precarious stacks of half a dozen counters but in actually planning their attacks. By being able to see their units quickly and what is arrayed against them, the player can quickly and readily make meaningful decisions about how best to go about doing what they need to do. As opposed to hunching over those large stacks desperately searching for a few more Combat Factors to get to the next odds column on the CRT. This keeps the game play moving along and Hundred Days 20 did this very well and created some palpable tension as we were trying to break through with our limited units and push ahead.

Combat Systems in introductory-level wargames can also be quite rewarding if done properly. I really enjoy a good Combat Results Table but know people that are intimidated by this means of determining the outcome of combats. CRT’s are used in some introductory-level wargames but not all of them and I always really enjoy the ways that designers try to think outside of the box to simplify this process while simultaneously keeping it engaging. A few years ago, I played 1944 Battle of the Bulge from Worthington Publishing and really enjoyed the way they dealt with combat in this Bulge game in under 2 hours. One of the more interesting parts of the game is the simple combat system. This game doesn’t use a CRT and the dice you roll are not looking for a specific number but rather a combination of symbols shown on them. First, you need to understand the information found on the counters and how that translates to the combat system. Across the bottom of each counter, appears 3 numbers. Left to right the numbers stand for Dice Rolled in Combat (DRC), Strength Points or unit steps (SP) and Movement Points (MP). For example, an Armor unit will have 2 to 5 dice that are rolled in combat, 1 to 6 steps and 5 or 6 movement. The important number to know for combat through is the DRC.

The next thing you need to understand is the makeup of the dice. The dice are 6-sided dice but they only have 2 results on each die, a NATO symbol for Infantry and one for Armor. The other 4 sides on the die are blank. Yeah, you read that right, a 6-sided die with only 2 results. There are lots of opportunities for those dice to roll nothing for you and that is both a blessing and curse as you want them to roll well for you but not for your opponent as each combat is simultaneous and both sides get to attack.

The process of attack requires that the attacking player spends 1 Resource Point to attack a unit in a target hex. If the units used to attack are from different Armies/Corps, then 2 RP’s will have to be spent. This simply represents the concept of cohesion of command. It costs a bit more to order units from another formation. As I mentioned before, combat is simultaneous so both players roll for attack and defense at the same time. The attacker will total the number of dice to roll for the attacking units, using their units DRC to determine the base number of dice and then modifies that total by any terrain and whether they are out of supply. The defender then adds any terrain modifiers to his defending unit’s dice and reduces dice if out of supply. The players roll their attack and defense dice. A hit will be scored on opposing units for each symbol that is rolled that corresponds to an opposing unit’s symbol. It is a simple, fast process without the need for CRT’s or complex calculations. Armor symbols rolled will effect Armor units but also can be used to reduce an Infantry unit if no Armor is present. These symbols work really well. It is simple and straightforward but really creates some interesting decisions. The main decision is understanding how the terrain will affect your attacks and whether you want to actually do that attack. Forest will apply a -1 die result an any unit attacking into it while Rough terrain will apply a -1 for each attacking Infantry and a -2 for each attacking Armor unit. Cities and Towns also provide a +1 or +2 die bonus to defending units. These choices must be taken seriously and can effect how you go about dislodging your opponent from that choice rough terrain.

After understanding the negative modifiers on your dice pool due to terrain, sometimes you just have to throw caution to the wind and attack. It may not be the best attack, but as the Germans you really have no choice but to keep slugging away until you eliminate those stubborn defending Allies. After all, the Americans did respond to the German plea for surrender at Bastogne with the famous retort Nuts! An understanding of the dice, and how they can benefit you or hurt your efforts is key but you almost must understand that time is limited and you have to make progress. But the dice are fickle and sometimes you will roll 6 dice only to see no hits and sometimes you will score 3 hits on just 3 dice. You must know that the dice are bad….but they are bad for you both and that is what makes the combat system charming. It is simple and just works.

All in all, introductory-level wargames can be a really great intro to the genre and I really do enjoy lots about them. But, as in all things in life there are things that I don’t like.

Hate

I have found where designers who are doing these introductory-level wargames do not necessarily present the rules in a manageable format for new wargamers. They take a lot of assumptions of concepts in the rules and don’t necessarily give enough context or even good examples to aid new players in picking up the concepts. If you are promoting your game as an introductory-level wargame, you need to keep in mind the audience. Assuming that they will understand things like DRM, CRT and ZOC is not going to go over well as players will struggle with these concepts as they are learning. Acronyms are sometimes overused and lead to confusion and slow intake on their meanings. I am a fan of acronyms as long as a further in-depth explanation of the points are included at the beginning of the rules. But when not included, this leads to confusion and a difficult time in internalizing the concepts. And if new players struggle to even learn the basics of the game, they are less likely to actually play the game to find out if they enjoy it or not. To combat this, diagrams and pictures are very helpful as most gamers are visual learners and can miss important concepts from only the text explanation.

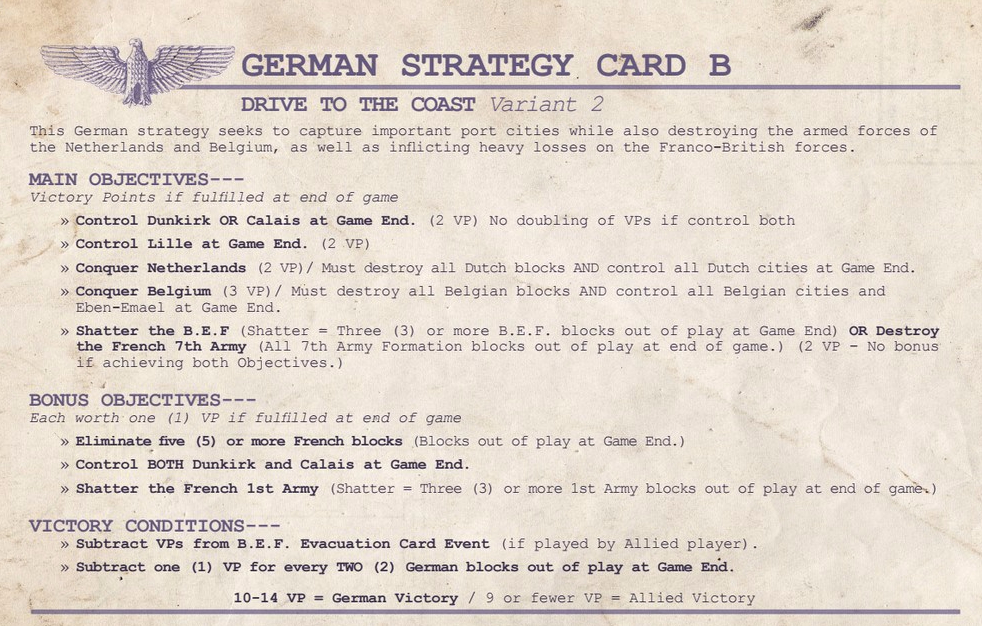

One other thing that I dislike about introductory-level wargames is that sometimes the games are just too simple and this leads to a lack of replayability. These games often come with a limited number of scenarios or gameplay variations, which can further exacerbate the problem of replayability. Once players have experienced all the included scenarios, they may find little incentive to revisit the game. I like the way that Worthington Publishing has tackled this problem in a few of their introductory-level wargames such as Dunkirk: France 1940 designed by Doug Bryant. Dunkirk: France 1940 is a very basic introductory-level wargame that included some alternative victory conditions in the form of cards. Early in the design process, Doug found that his game was fairly repetitive in that the same objectives were frequently the targets for the Germans. Coming up with the German Strategy Cards (which, in effect, allow the German player to pick their own Victory Conditions at the start of the game) provided variety for the German player, as well as providing an additional layer of suspense, as the Allied player will not know for certain until the end of the game what specific strategy the German player was pursuing.

The final thing that I want to point out that I do not like is that sometimes games leave out some of the really important and more detailed elements of a wargame such as the more important Zones of Control. I found this problem in the very introductory-level wargame Paul Koenig’s Market-Garden: Arnhem Bridge by Victory Point Games. In looking at the game, the main focus and goal is for the Allies to move toward Arnhem bridge and capture it. The path to move to the bridge is through fairly dense urban hexes with a road leading right up to the bridge ramps. Strategically, a German commander would have lined the streets with their best units to prevent the enemy from simply riding right down the middle of the street to the bridge. This commander would have given orders to fire on anything approaching and would have had reserve units located in the buildings to the left and right of the streets to prevent small unit interdiction through the back alleys. These units would have taken up positions to bring heavy fire upon any approach hex and this is typically simulated in other games through the use of a Zone of Control.

This ZOC would cause advancing units to stop while taking fire from an adjacent unit but in this design, the units just kind of ride on by, waving to the nasty MG-42 nests on the 2nd floor of the buildings and blowing kisses to the Panzers hidden in or behind the piles of rubble! In reviewing the history of the campaign, one of the major problems the British had in advancing on the bridge was that relatively small German forces had taken up positions in the woods and on the outskirts of the city and effectively pinned down most of the advance of British forces toward Arnhem. This, in my opinion, is a major design flaw and should be house-ruled or cause a redesign of an otherwise fun and good playing game. I have illustrated this point with the pictures below where the British 4-6 Infantry unit simply moves right down the street between 4 better groups of units (an 8-9 Tank, three 6-8 Mobile Infantry and a crack 6-6 SS unit) without taking fire or being stopped! Seems silly doesn’t it?!?

I hope that you enjoyed my look at the introductory-level wargame. I think that introductory is sometimes seen as a dirty word in some circles in our hobby, and I get the reasons for the opinion, but introductory-level wargames are a needed part of our hobby. They have a place at the table and can be used to bring in new initiates to the order. If used properly and taught well. I want to see our hobby continue to grow and will do my part to do that the way that I see best.

Please let me know some of your thoughts on introductory-level wargames and thank you for reading.

-Grant

Good write-up!

I started with heavier games in the 1970s, and still prefer long hex and counter campaigns. For me, there is a place for smaller lightweight hex and counter games not as an entry, but as a quick playing break from a longer campaign.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good point. Sometimes a game that plays in 2 hours is needed after slogging through a multi-day campaign.

LikeLike

Good article; being introductory does not mean being simplistic. I still love a lot of introductory games (you know my crazy affection for Commands Colors Ancients) while being able to digest very complex titles (see Pacific War or other, 60-pages-rulebook titles). A good introductory game will allow new adepts of our beloved hobby to get hooked by it, but will still be interesting from time to time for experienced players. This is mastery not easily achieved but definitely several titles hits this sweet spot – already mentioned Commands & Colors genre, Julius Caesar from Columbia Games, Sekigahara, Undaunted, Time of Crisis, Shores of Tripoli to name only a few.

Please continue the series! Always love those topic which generate conflicting emotions and reactions 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. Introductory games are very much needed in our hobby but they tend to be put down a bit. I like them and have used them in many ways.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is my feeling – and approach – too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Most definitely there must be introductory elements in any endeavor worth undertaking. Who ever learned to run a race without learning how first to walk? Sometimes as we get older, get so comfortable with our day-to-day processes, there can be a propensity to forget what is was like to grasp new concepts and to strive to achieve competency wirh new challenges.

Mr. Berg’s credentials were established some time ago, but at best comments about ‘elitist hobby’ were and are myopic and exclusionary. I wish I had better introductory offerings when I was a teenager many years ago wanting to ease in to the kinds of stuff that was a step beyond ‘kid games’. Today the opportunities seem much expanded…a good thing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Introductory games can also be a good intro for even experienced gamers into a campaign/war/century that they’re not familiar with. I’ve been playing since the ’70s, but if I want to try a game on Napoleon’s campaigns, I think I’d prefer something more intro-level.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Except for your point about the omni mandatory use of ZOC I agree with you.

A broader product palette is good for the hobby. I can’t see any negative effects. Even someone with the intellectual capacity and interest in history may not have the time or space to play “real” wargames.

About ZOC: Play Liberty Roads or Victory Roads. No ZOC! Such a great system.

LikeLiked by 1 person