I love little games with a bit of kick! A few years ago, we came across a very cool little small box game called Tetrarchia 2nd Edition from Draco Ideas. This was a cooperative game dealing with 3rd century Roman rule and saw 1-4 players working together to save the empire from invading Barbarian armies. We enjoyed our experience with that game very much and recently I found out that the designer Miguel Marqués was working on a follow-up game using similar mechanics but that focused on the 2nd century Roman invasions of Hispania aptly named HISPANIA. Ahead of the Gamefound campaign, which is scheduled to commence as of April 16, 2024, we reached out to the designer to get an inside look into the game and how it differs from Tetrarchia.

Grant: First off Miguel please tell us a little about yourself. What are your hobbies? What’s your day job?

Miguel: Hi Grant, thanks for this opportunity to talk about HISPANIA, and my approach to the hobby in general. I was born in Spain but I came to France as a researcher in nuclear physics already 30 years ago. Besides my love for science, my hobbies have always been sports, history and boardgames. Already as a kid/teenager I fused them together by designing boardgames about sports and history!

Grant: What motivated you to break into game design? What have you enjoyed most about the experience thus far?

Miguel: Back in the 80’s the world was very different. Without internet, access to games was hard, and the few ones I could buy did not satisfy me. I started thus designing them, but only for me. I made games about tennis, soccer and basketball, and with the latter two I even organized “world championships” with some friends! I also bought books on battles or wars, I drew a board by hand and I made up rules. I remember a battle for Iceland between the US and Nazi Germany! But after some games, mostly solitaire, my designs ended up inside a drawer.

It was only in 2012 that I decided to publish a game thanks to an opportunity offered by the Spanish publisher nestorgames. I refined my old basketball game from 1981 called BASKETmind, and I officially became a designer! It was a very important milestone, a turning point that pushed me to publish other games.

Grant: What is your upcoming game HISPANIA about?

Miguel: It recreates the Roman conquest of Hispania. This conquest is not very well known, even in Spain! But it was a very long process that lasted almost 200 years, right between the defeat of the great Hannibal and the rise of Augustus and its new empire. There are almost no games on this conflict, and I hope that mine will attract the interest of people in not only the game but also in the period itself.

Grant: What does the title of the game reference?

Miguel: The Iberian Peninsula had no territorial identity before the Roman conquest. It was inhabited by many independent tribes and peoples, without cohesion. The Carthaginians were the first to extend the Mediterranean coastal colonies significantly inland, specially the Barca family, but they were cut short by the Roman victory over Hannibal in the Second Punic War. Now the Romans felt powerful enough to conquer the whole peninsula, which they would call “Hispania”.

Grant: Why was this a subject that drew your interest?

Miguel: In 2015 I published Tetrarchia, a cooperative game on Diocletian’s tetrarchy in which from 1 to 4 players defend the Roman Empire against the Barbarian invasions. A compact game with very simple rules but that combined to provide the player with very different challenges. The game has been so successful that my present publisher, Draco Ideas, asked me to transfer the mechanics to an episode of Spanish history. And I finally found it, the Roman conquest of Hispania.

Grant: What is your design goal with the game?

Miguel: Mechanically, the same goal I fixed myself with Tetrarchia: simple rules, simple pieces, some randomness but with tools allowing players to handle it, easy to learn (and remember) but hard to master. Thematically, however, the goal was very different. The engine of Tetrarchia had been defensive, it recreated the sense of urgency in an agonizing defense against unexpected attacks. In Hispania, I needed an offensive engine, so as to recreate the sense of penetration into hostile territory.

Grant: How much does HISPANIA compare and contrast with your previous Tetrarchia?

Miguel: Tetrarchia was an original idea that I had not expected to be so successful. With HISPANIA, 8 years later, I benefited from my greater experience in game design and the feedback from thousands of Tetrarchia players, very positive but with eventual suggestions that I had written down. When I sat down in front of an empty page I thought about the way to modify the system by making it even simpler (no rules exceptions, fewer actions and pieces) and by improving some mechanics (Hispanic and sea movements, sieges).

I also added mechanics (denarii, Roman roads) that allowed a better handling of randomness. The game engine is still a couple of dice, Roman and Hispanic, but good players will not rely on luck, with experience they will find the tools to “control the chaos”. This is what I like in games: some uncertainty that we do not control itself but with mechanics that allow us to handle it. The result has been a game even more dynamic, tense, and fun.

Grant: As a cooperative game, how do players work together?

Miguel: HISPANIA is a game for 1 to 3 players. The Roman generals that must conquer Hispania are always three, the praetors of the two starting Roman provinces (Ulterior and Citerior) and the consul sent by the senate. Any number of players will handle these characters, that take their turns one after the other without any explicitly imposed cooperation rule. However, the combat mechanic in particular makes victory impossible without cooperation between the three characters, as the players will soon discover.

Grant: What is the ultimate goal of the game?

Miguel: The non-Roman part of the peninsula (most of it) has been divided into 6 areas, called “provinces” (even if they were not yet) for ease of play, and in each of them there is a main city called a “capital”. The goal of the players is straightforward: place a Roman garrison in the 6 capitals before the reserve of revolt pieces runs out.

And there is a twist that generates a lot of tension at almost any difficulty level. At the end of each round, the players must remove a revolt piece from the reserve! Therefore, the game becomes easier to lose the longer it lasts. Moreover, the removed revolt goes into a time track with 11 spaces, covering the last two centuries BC of the real conquest, and the players also lose if these two centuries pass. They must win in at most 11 rounds.

Grant: What different units and pieces do the players have access to?

Miguel: I don’t like numbers or text on my pieces, nor any kind of table for combat, abilities, movement…none! Therefore, the pieces are only wooden meeples and discs, colored for Rome and black for Hispania. The Roman meeples are the three generals with their armies, supported by the Roman discs, their garrisons. The Hispanic meeples are the armies players will fight, supported by the Hispanic discs, the revolts.

Grant: What is the layout of the board?

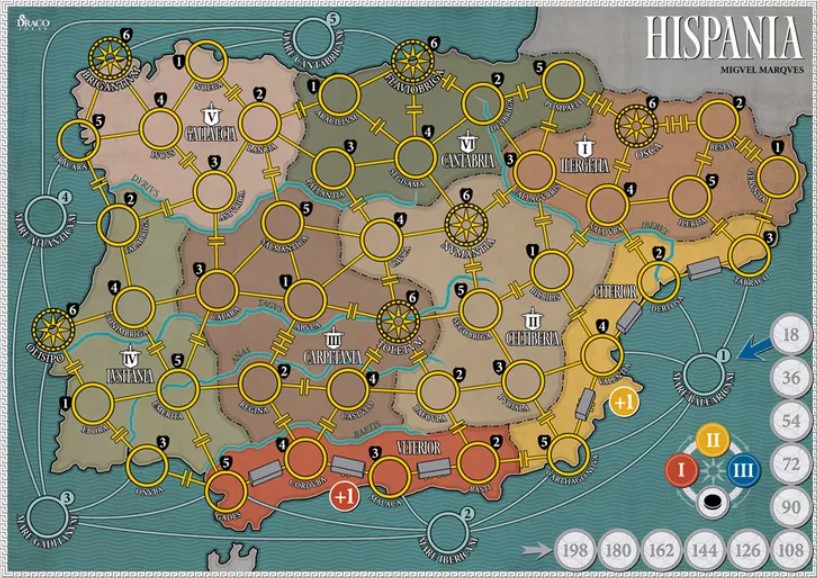

Miguel: My starting point was a Hispania map of the era, then I started to transform into the board I had in mind. The Roman base was narrowed into the Mediterranean coast and the map boundaries slightly distorted, so that the rest of Hispania could be organized into the areas with the cities I needed. I wanted to focus into Hispania as a battlefield, and thus I ignored connections towards the north-African coast and through the Pyrenees. All the action takes place inside Hispania.

Grant: How are the cities and spaces divided up?

Miguel: As in Tetrarchia, the engine of two d6 requires 6×6=36 spaces. In Tetrarchia I had 6 regions with 6 provinces each, in HISPANIA (“region I” of Tetrarchia by the way!) I zoomed out to have 6 provinces with 6 cities each. As I said, these “provinces” are somehow artificial, but I selected their names from the most significant Hispanic peoples (there were many more) that inhabited those areas. Once I had the provinces, the board spaces where the cities, and I went through a selection process in which many compromises were made. The game takes place over two centuries, and some locations that started as Iberian villages became Roman cities later.

Grant: What role does geography like mountains and rivers play in the game?

Miguel: I prefer point-to-point maps with the board spaces at points connected by links, which can thus contain in an abstract way the movement information. Movement through the links that connect the different cities is straightforward: 1 point/coin per segment. The more or less flat geography is represented by continuous (1 segment) links, but rivers and mountains are illustrated by broken (2 or 3 segment) links. Players will enhance their movement ability with the help of the Roman road pieces, which let them ‘flatten’ some of the broken links.

Grant: I see where players can choose their difficulty level. How does this change and what challenges does it create?

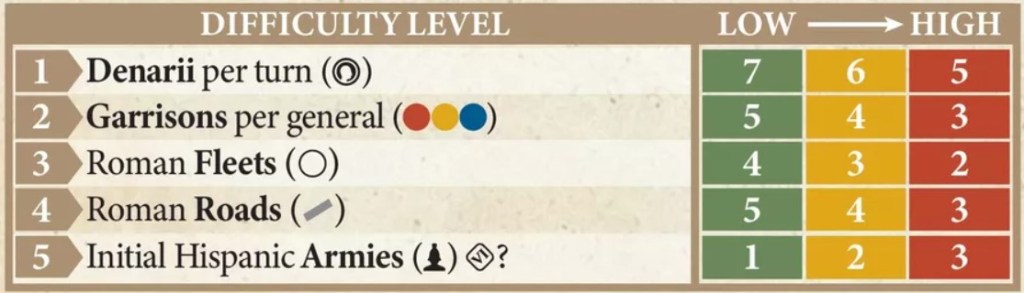

Miguel: A key element of these designs is the difficulty table. Cooperative or solitaire games often fail because some players find the few levels proposed too easy or too hard. In HISPANIA (and before that in Tetrarchia) this cannot happen! The difficulty choice remains simple, you only need to choose a value easy/medium/hard for a few parameters, but this generates a number of levels of 3 to the power of the number of those parameters. In Tetrarchia those were 4, so you could choose among 81 levels (3 to the power of 4). But in HISPANIA there are 5 parameters, so you can choose among 243 levels, three times more!

It is not just about quantity. In HISPANIA, those parameters are the numbers of: coins/points per turn, garrisons per general, fleets, roads, and initial Hispanic armies. The medium level has respectively 6-4-3-4-2, and then you can shift +-1 any of them. This allows to make the game easier or harder on the specific aspects of your choice. And independently of the player experience, any player will find the easiest level (7-5-4-5-1) very easy and the hardest level (5-3-2-3-3) a real nightmare! Therefore, any player will be able to find their own sweet spot within the table.

Grant: What is the general Sequence of Play?

Miguel: The game is played in a series of at most 11 rounds, comprising a turn of each of the three Roman generals. In the Roman phase of the turn, they will move through HISPANIA besieging cities in revolt, placing their garrisons and attacking armies. In the Hispanic phase, a random threat (revolt or army) will appear in a Hispanic city, and all the armies on the board will move within their province, spreading the revolt further. At the end of each round a revolt is placed on the next space of the time track, bringing the endgame closer two-fold: smaller revolt reserve and fewer rounds left.

Grant: How is the AI controlled?

Miguel: The core design element is the two-dice engine. With only a Roman and a Hispanic dice the game handles combat, but also the arrival of revolts and armies and the movement of those armies. In the Hispanic phase of each turn, the players will roll the two dice and check the content of that city (province banner and city shield coordinates). If the city is not protected by Rome, a revolt will appear, but if it had already a revolt an army will appear! And then the armies move to a neighboring city within their province, with a roll of the Hispanic die dictating to which one when there are several possibilities.

The arrival of revolts and armies in given areas is thus a matter of probabilities, as well as the destination of most of the armies. Players will have to evaluate them, plan their strategy according to the expected outcomes, but have also alternative plans ready in case the outcome is not what they expected.

Grant: What actions do players have access to?

Miguel: Only four. They can spend their coins in: 1) moving their general or any fleet to a connected space; 2) placing or removing their garrisons in their city; 3) besieging a revolt in a connected city; and 4) attacking an army in a connected city.

Grant: How do players control and spread their influence and reach through the various cities and territories?

Miguel: They move through the Hispanic cities and protect them with garrisons. However, there is a basic rule that dictates the game flow: capitals can only be garrisoned when their whole province is free of revolt. Since during setup revolts are randomnly placed in one city of each Hispanic province, no capital can be garrisoned at start. Players will thus begin removing revolts and limiting their spread, in order to be in position to attain the game goal.

Grant: How does combat happen?

Miguel: The Romans can choose to attack revolts or armies during their Roman phase, but they can also be attacked if they or their garrisons block the movement of the armies during the Hispanic phase. The attacker, Roman general or Hispanic army, rolls the corresponding die and adds to the result his own discs connected in a group to him. However, when the Romans attack they must spend from 1 to 3 coins, that will also add to the result. Therefore, crucial attacks can be supported with more coins at the price of having fewer coins left for other actions.

If the defender is a Roman general or Hispanic army, the combat value is also given by his die roll plus his own discs connected in a group to him. However, if the defender is a disc, be it a revolt or a garrison, the combat value is given by the city shield. Therefore, important cities will be harder to subdue.

There is a final touch that gives most of the cooperative sense to the game. Other generals or armies can reinforce the combat! Any of them connected to their enemy multiplies their corresponding combat value x2. Since these are games in which you must optimize your resources, especially at higher difficulty levels, reinforcing your combats is the most efficient and inexpensive way of avoiding randomness. You should deploy your garrisons for your own support, reduce or cut the revolt base to minimize theirs, but overall plan the approach and timing of your attacks so that several generals reinforce each other.

Grant: What are Revolts and how do they vex the players?

Miguel: They vex players three-fold. First, they block their movement, Romans cannot enter cities in revolt (an important simplification with respect to Tetrarchia). Therefore, if you want to move across a revolted area you must open the way. Second, they prevent you from garrisoning the province capital, so you must clean the whole province before you do. And finally, they support the Hispanic armies in combat. You will need to cut the armies from their revolt base in order to make combat odds tilt in your favor.

Moreover, there is a new dimension. I have simplified the rules but also the pieces, the unrest (gray) discs of Tetrarchia, precursors of revolts, have gone. However, I have succeeded in reflecting a threat gradient with only one piece type by allowing the stack of up to 3 discs per city. This means that small areas of the map can concentrate a lot of revolts, which will become very hard to remove if they pile up in important cities. Piles of revolts must be removed one at a time.

Grant: What different modular expansions and historical scenarios are included?

Miguel: The basic game has a few simple rules, so that a broad category of players can feel comfortable from the start. But once it has been assimilated, we propose several add-ons. They are simple too, but as in the difficulty table a few simple things can add up to build very different challenges! There will be new characters, like the Roman proconsul that will help the three generals or like Viriathus, a powerful Hispanic army.

These new characters will be put into action in a series of historical scenarios. We will define the list during the campaign, but we do know that there will be several of them, the history of the conquest is full of special events and famous characters. These scenarios will place players at the start of a given historical campaign to let them see if they can relive or change history.

Moreover, we will propose optional rules. For example, special powers for each Roman general or the ability to remove and rebuild Roman roads, that will help the players. On the other hand, new obstacles like the Atlantic pirates or the most important variation, a Hispanic player that will guide the resistance!

Grant: How do they change the game?

Miguel: I said that the difficulty table generates 243 levels, but you shouldn’t play them all, at least I did not! The table is huge so that any player can find their own enjoyment space within, by making some parameters harder and/or others easier. The special characters and variants will enhance this ability. Players will be able to move further in the difficulty table by using favorable characters and/or variants, and the other way round, move to easier levels and maintain the challenge by using unfavorable ones.

Of course, the competitive variant will change the game the most! The Romans will be even more on their toes, knowing that they are playing a tense game but against a really intelligent opponent. I did not design the game with the competitive aspect in mind, my design goal was exclusively cooperative, but this twist works very well for those who want to have a completely different experience with the same pieces and rules.

Grant: How does the competitive version work?

Miguel: Do not expect an independent Hispanic player that has all the choices during the Hispanic phase, the game would not work. The Hispanic engine remains the same, with the die rolls governing the Hispanic behaviour. However, the new player will have 2 coins every turn that will allow him to guide some of the choices. By spending those coins he will be able to reroll some dice, choose the destination of an army, attack garrisons or generals connected to him, or even add his coins to an attack, like the Romans do.

Grant: What type of experience does the game create?

Miguel: Traditional wargamers often dismiss light wargames as “abstract games”. I don’t agree. Any game is an abstraction, and my design goal is to select those abstractions so that they convey the historical character feelings and experience with the lowest rule/exception burden. Players playing HISPANIA will feel like Roman generals entering uncharted territory. They will store the rulebook back in the box and concentrate on the board, the few pieces and the couple of dice. They will not say “I place a blue disc on space II-6”, they will say “the consul occupies Numantia”. And they will tell the game they played as (fictional) history.

Grant: What do you feel the game design excels at?

Miguel: It is very easy to force a given historical storyline with many explicit rules, event cards and exceptions. With Tetrarchia I was surprised by how much some events happened without any rule enforcing them. In HISPANIA I went even further in the removal of rules and exceptions, so my surprise was even bigger! Without artificial guidance by explicit rules, and despite the random character of the game engine, players will often find themselves fighting the last Hispanic tribes in the north of Hispania by the end of the millenium, as the first Roman Emperor did!

Grant: What are your future plans for the series?

Miguel: There is no series as such. After the success of Tetrarchia, it was only chance that made me search for a suitable period in the history of Spain and that this period involved Romans. However, the design exercise of adaptation and transformation of the original system has been very pleasant, and I am really proud of how HISPANIA plays. Now I cannot avoid thinking about other possibilities, and I have a few in mind. Some would play like Tetrarchia, others like HISPANIA, and even others like none of them. But they correspond all to different periods of history.

Grant: What other designs are you currently working on?

Miguel: In the past I used to think about several ideas in parallel, but now that I’m in the logic of publication I need to choose one that will realistically materialize. Among my ideas based on a similar two-dice engine there is one that I am almost sure will work, so I think I will prioritize it. I prefer not to give more details, because once I thought of it it seems so straightforward that I think others could make it. And in parallel I have an idea of a very abstract World War II game. It may be too abstract, but I have the feeling it will recreate the conflict quite well…only time will tell!

HISPANIA will be coming to Gamefound as of April 16th so keep your eyes open for the start of the campaign. In the meantime, if you are interested in Hispania, you can learn more about the game by visiting the Gamefound preview page at the following link: https://gamefound.com/en/projects/draco-ideas/hispania

-Grant