I have been pretty impressed with the design approach of Carlos Márquez Linares. Keep in mind though I have yet to play any of his games but they just look very thoughtfully approached and designed that my interest is always piqued. Such was the case with his first game The Other Side of the Hill from NAC Wargames that ran a successful Kickstarter campaign at the end of last year. He also has a design with GMT Games for a card based deck-building strategy game on the struggle between Empires during the 19th century that looks really interesting called Imperial Fever: Great Power Competition in the Late 19th Century. I reached out to Carlos and he was more than willing to share on his newest design.

*Please keep in mind that the artwork and layout of the various components shown in this interview are not yet finalized and are only for playtest purposes at this point. Also, as this game is still in development, card and rules details may still change prior to publication.

Grant: What is your upcoming game Imperial Fever about?

Carlos: Imperial Fever is a game of historical simulation that recreates the fascinating period between 1885 and 1914. Up to four players take on the roles of the Main Powers in that period and vie for dominance in the spheres of diplomacy, military power, naval hegemony, colonial expansion and national prestige. These powers are the United Kingdom, France, the Central Empires (including Germany and Austria-Hungary) and the Emergent Powers, ( including the USA and Japan).

Grant: What does the subtitle “Great Power Competition in the Late 19th Century” mean? What do you want it to convey to players?

Carlos: Imperial Fever is game of historical simulation, not a wargame. Although there is plenty of conflict and tension between players, players never clash with one another in open war. Actually, if this happens, it will trigger the outbreak of WWI and the end of the game. Do not get me wrong, players will have to embark on military operations in the colonies and wage wars with minor powers, like the Russo-Japanese War, the Spanish-American War, the Anglo-Afghan War, etc. Each

player has at least one war to wage. These open military conflicts will shape the game, but they are only one of its aspects, since the scope of the game goes beyond military conflict and into the realm of economic, political and diplomatic competition.

Grant: Are you worried about the game being seen as focused on colonization and gaining resources from other cultures? What you say to someone concerned about this aspect?

Carlos: As you may have assumed from the previous answers, the game is certainly not focused on colonization and garnering resources from other cultures. Obviously, it is impossible to design a game attempting to simulate international relations in the period 1885-1914 without including the frenzied race for colonies in that time. The aim of the design is to help players understand the motives behind this mindless competition, which was not always caused by the desire to garner resources, but more frequently by the need to possess a captive market for products manufactured at home. Even more frequently, colonies were established just out of a perverted sense of national prestige. Only this explains why huge swathes of Africa or Asia, of doubtful economic interest at the time, were claimed by European nations. Very often this was initiated by individuals without support of their governments, which were later forced to step in and take control of territories they were never interested in when these initiatives were faced with opposition from local or international powers. Think of Gordon, the Zulu War or Namibia. This colonial race actually interfered with the diplomatic, military or economic policies of the powers, and the way it is implemented in the game illustrates the motivation behind colonialism in this era.

Also, in Imperial Fever players are not asked to just mindlessly harvest resources from their colonies. Once a colony is established, its owner has a choice between plundering its resources, exploiting them or investing to improve the living conditions of people in the Colony, which was seldom the favoured option. Plundering resources is going to give players a large influx of immediate resources but at the cost of losing prestige for their methods. Think King Leopold II of the Belgians in the Congo. Exploiting resources will yield benefits in the long run and will not cost prestige, but it will not grant you prestige either. Finally, investing in the colony is expensive, but it will give you prestige. It is difficult to find a good historical example of this, so maybe players can demonstrate there was an alternative to the historical modes of colonial exploitation.

I do not think that designers should avoid historical topics because they are controversial. On the one hand, that would leave precious few historical topics to explore, sadly enough. On the other, one of the aims of a game of historical simulation, apart from entertaining, is helping players understand why history happened the way it did. Looking at our history from a critical perspective is not only good, it is necessary, but it will be a frivolous, pointless task unless this critical perspective is based on actual knowledge of the historical processes and factors. It is not the topic we should be concerned about; it is the treatment. Is colonialism glorified or whitewashed as sterilized, abstract resource gathering, or is it portrayed as one more ruthless, sometimes mindless factor in big power competition? It is this second approach that Imperial Fever aims at providing. Even the title, which includes the word “fever”, gives an idea of the rationale, or lack thereof, behind Empire building in the period of 1885-1914.

Grant: What other games on the subject informed and influenced your design?

Carlos: Sometimes it is difficult to identify games that inspire a design, but this is not the case with Imperial Fever. If we look at the topic, the inspiration is Pax Britannica from Victory Games. Imperial Fever aims at simulating the same period and including the same elements: diplomacy, economy, politics, military and naval power, colonial expansion… If anything, the relative importance of colonialism is diminished in Imperial Fever if compared with Pax Britannica.

On the other hand, from the point of view of game design, the inspiration for the mechanics of Imperial Fever is Time of Crisis from GMT Games. Both are deckbuilding games, but I

have introduced some innovations to the application of this mechanic that will allow Imperial Fever to be closer to the historical events and less of a sandbox game than Time of Crisis. The topic, scale and goal of both games are different, and this implies adapting the mechanics. This is the reason behind some tweaks to the deckbuilding mechanism, such as Strategy Cards and Policy Tiles. Imperial Fever also has a resource management side which is central to its design and helps simulate the economic constraints and political choices of powers at the time.

Grant: Using Pax Britannica as a model, how does your design attempt to answer the following statement to make a “better-balanced game covering this period for fewer players”?

Carlos: Pax Britannica was a game for four to seven players covering the same period as Imperial Fever, but it took much longer to play. There are many aspects to recommend this game, but it is definitely a game of a bygone era, of a time when it was easier to gather a bunch of friends to play a boardgame over a weekend. Apart from the duration of the game, Pax Britannica had balance issues. With up to seven players, there was huge asymmetry between them: the UK was involved all over the map and had the income to act multiple times in various places during a turn. The agency of the players diminished progressively with France and the Central Empires, was greatly reduced with Russia, the USA and Japan, and was close to none with Italy. To compensate for this, Victory Points at the end of the game were modified with fixed divisors (a big divisor for the UK) and multipliers (a big multiplier for Italy). This implied that Italy might create a couple of colonies while the UK, France and the Central Empires divided the rest of the world among themselves, but those two colonies could be enough to get Italy a victory. Reducing the number of players, combining powers together, and widening the scope of the game beyond the competition for colonies allowed me to create a more balanced game where players enjoy similar agency.

Please don’t get me wrong: Pax Britannica is a wonderful design that I would still play today if I could get six or seven players to commit over the time that a game requires. There are design elements in Imperial Fever that are directly inspired by Pax Britannica, such as the possibility of the game ending by the outbreak of World War I. I just liked the topic of Pax Britannica so much that I

thought it deserved a game with more modern mechanics and that was playable in under four hours by no more than four players.

Grant: Why was this a subject that drew your interest?

Carlos: It is a common statement that in order to understand the world today we must understand World War I. The Great War represents the end of a centuries-long era and ushers in the modern world. It marks the beginning of the end of European hegemony and the emergence of the powers that will dominate the world during the 20th century. It involves the increasing use of technology in warfare in a race that we are still on and makes it possible to kill at an industrial rate. I agree that we

cannot understand the world today without learning about World War I. But World War I did not just happen out of the blue. Indeed, it was just the visible, terrible manifestation of tendencies that must have been developing for a long time before 1914. The industrial revolution (both industrial revolutions), technological and scientific advances and their application to warfare, colonial expansionism, the need for bigger markets, the construction of world-spanning empires and the need for a navy to protect them, rampant nationalism… All these processes manifested themselves openly during World War I, but they had undoubtedly appeared and developed well before Francis Ferdinand was shot in Sarajevo. You cannot understand contemporary history without studying World War I, but you cannot understand World War I without studying the feverish, intense period between 1885 and 1914.

Grant: What is your design goal with the game?

Carlos: In connection with the previous answer, the aim of this game is to help players understand the period that preceded World War I and the dynamics and processes that led to that great catastrophe. That is why the game transcends colonialism, although it includes it, because it is concerned with the mindless competition among great powers that led to World War I. And obviously the game also seeks to entertain.

Grant: What elements from the late 19th century are most important to include in the design?

Carlos: In order to simulate great power competition in that period, I needed to include the naval race, control of the ocean lanes, the arms race, diplomatic competition, economic supremacy, control of key strategic areas, national prestige, national stability, the economy and, naturally, colonial expansion. It was the design intent that all these systems should be connected. For instance, establishing colonies yields resources for your economy, but also prestige and naval bases. Expanding your army costs resources, but increases national prestige, provides free diplomatic actions and may help you with foreign wars. Building naval squadrons increases your naval power, allows you to control Naval Zones, helps you win wars with Minor Powers and provides national prestige, but it consumes resources and ships become obsolete and the naval race becomes increasingly expensive as naval technology evolves from ironclads to battleships to dreadnoughts. It was not only important to include all these aspects, but to have them interact with one another

to simulate the decisions and policies of powers at the time.

Grant: What challenges did you have to overcome to realize your vision?

Carlos: It was very important to me to make it clear that Imperial Fever is not a game about

colonialism. Colonialism is included, as it would be impossible to simulate international relations in that while ignoring it, but I was more interested in the dynamics that led to World War I. It was important to have four powers with equivalent agency, that is, not only with an equal opportunity to win the game, but with plenty of things to do to keep them constantly invested in the game, watching what the other players are doing while trying to optimize their actions. I also wanted the game to play in under four hours, so it was necessary to carefully measure what players could do in that time, so that it could match historical developments. I am happy to say that the game end matches plausible historical outcomes. Finally, I wanted players to feel under pressure because of the actions of other players, but also because the end of the game is out there, drawing ever closer. It is a game of competition and, as such, there is an element of racing in it. Playtesting has showed that players feel the game ends too soon, that there were lots of things they wanted to do, but just did not have the time to do them. I think it is a good sign when players feel that the game is too short, especially after an average of three and a half hours of play time. This vague feeling of discontent also pushes the players to want to play again to see if they can maximize their options or whether a different strategy might work better.

Grant: What research did you do to get the details correct? What one must read source would you recommend?

Carlos: Designing an historical simulation game implies creating an abstract system that models the forces, the circumstances and events that make up a certain historical period or event. In order to do that, the designer must identify the elements that will need to be present to properly integrate the abstract system and the interactions between them. For me it is impossible to do that without reading extensively on the period in question, taking into consideration diverse ideological perspectives and opinions, and also looking at motivations of each and every player involved in the overall game. This means that reading lots of books, papers, essays and opinion pieces is one of the most important things that any designer can do to get their game in the proper framework and setting.

I found that Robert K. Massie’s excellent book Dreadnought gave me the insight I needed on the international relations of the period covered by the game, as well as the actors and the motivations behind the decisions made by the United Kingdom, Germany and France at the time. If I had to recommend one book, it would definitely be Dreadnought. Actually, I toyed with the idea of using Dreadnought as the title for the game but changed my mind for several reasons. However, I think I it would be unfair to not also mention The Scramble for Africa written by Thomas Packenham. My understanding of the colonial race, its motivations and its horrible consequences, are indebted to this book and its approach to uncovering the issues behind the scramble. If you have the time and are interested in the period, please consider reading it as well.

Grant: Why is there no real focus on combat and armies? How does the game function without direct conflict?

Carlos: Imperial Fever is a simulation of the period leading up to World War I. There is no combat between players because there was no combat between the powers they represent in the period covered by the game. When it did happen, it led to World War I. This does not mean that there is no conflict between players. In the game, tensions and competition between players build up to the point when World War I breaks out, which ends the game, although not every game necessarily ends with the Great War. In this respect the game mirrors history. However, military power and military conflict do play a role in the game. To start with, players will compete for the biggest army and navy, and they will do so by expanding their armies and building naval squadrons, which will hasten the

outbreak of World War. Also, the fact that there is no armed conflict between players does not mean that there will be no combat. There will be plenty of fighting to do since players will have to fight wars against minor powers and organize military expeditions to establish colonies.

Grant: What nations are included in the design?

Carlos: In Imperial Fever up to four players take on the roles of Major Powers at the time: the United Kingdom, France, the Central Empires (Germany and Austria-Hungary) and the Emergent Powers (the United States and Japan). Aside from these Major Powers, the game contemplates the involvement of other influential nations at the time, which are considered Minor Powers for game purposes: Russia, Italy, Turkey, Spain, Portugal, Belgium, Holland and China. Their actions are handled by the game system and will interfere with the players’ goals and interests.

Grant: Why is asymmetry so key to your design and vision?

Carlos: The game needs to be asymmetrical from the simulation point of view and from the point of view of playability. From the simulation point of view, the playing factions need to be asymmetrical because the powers they represent were historically asymmetrical. The United Kingdom was a naval power, Germany and Austria-Hungary were continental powers with powerful land armies, France had a chip on its shoulder since the Franco-Prussian war, which motivated its actions, and the United States and Japan were newcomers to world power and were trying to carve out their own spheres of influence in areas where European powers had staked the claims centuries before. Asymmetry is also good from the point of view of playability. On the one hand, it is more interesting to play a game where other players are not doing the same things you are doing or at least they are doing them in a different way. On the other hand, asymmetry implies that the number of games it will take a player to master the whole game increases because the experience gained when playing with a power is not applicable when playing another power. This boosts the game’s replayability and, in a time when gamers possess more games that they can possibly play, every incentive to bring a game back to the playing table is welcome.

Grant: How did you go about differentiating them on the strategic scale?

Carlos: In order to implement asymmetry, each power should have advantages and disadvantages. Asymmetry is so deeply ingrained in the system that it is impossible to summarize here all these differences and the way they interact. However, in General terms, the UK is strong at sea but has a weak army; France is strong in colonies but lacks a sphere of influence of its own to defend and benefit from. The Central Powers have the strongest army, but it demands lots of resources and they come late to the colonial and naval races. Finally, the Emergent Powers have more of their own spheres of influence to expand in (America and Korea) and up to three wars to win connected to them but are all but cut off from establishing colonies.

Grant: How does the game use deck building? Why did you feel this was an appropriate mechanic for the subject?

Carlos: Deck building is the essential mechanic of the game. Players will have a hand of six cards each round, which may be reduced by their current Unrest level. They will have to play one of the six cards to determine turn order during the Initiative phase, so players actually have only five available Action Cards for the turn. Players take turns to perform actions, paying for them with cards of the appropriate type. Played cards are moved to the Discard Pile. After all players have played their hands, they choose a new hand from their Action Card Deck simultaneously. If they

do not have enough cards in their Action Card Deck, players move the Discard pile to the Action Card Deck and continue choosing cards. More powerful cards enter play as the game progresses and players can purchase them, in which case they are added to their Discard piles. Players can also trash less powerful cards to optimize their hands, but this is done at the cost of exhausting resources.

Many games use deck building as their basic mechanic, but the one that directly inspired my design was GMT’s Time of Crisis. Both in Time of Crisis and Imperial Fever, hands are not drawn randomly, but players choose their cards from their Action Deck. However, they will not be able to re-use any one card until they have played all their cards. There are several innovations with respect to the way

deckbuilding is used in Imperial Fever. First, players do not play their entire hands in their turn, but they take turns performing one single action until they run out of cards. Then they refill their hands simultaneously. This implies that turns are more agile, and players are constantly engaged in the game. Also, there is no downtime while players wait for each player to choose their hand at the end of their turn, since all players choose their hands simultaneously in the Upkeep Phase. Another

difference with Time of Crisis is that new cards are not available for all players to buy from the beginning of the game, but they enter play from the Main Deck in a random fashion, adding a layer of unpredictability to the system. Finally, some of those new cards are exclusive to one Power, which means that other players cannot purchase them. This helps compensate for the randomness of card entry and plays into the asymmetrical nature of the game.

Grant: What advantage does deck building give to your design?

Carlos: In my view, the two main advantages of deckbuilding as a mechanism are that it imposes limits and favours decisions. The deck building mechanism limits the number of actions a player can do in their turn. You cannot do everything you want, but only what your current hand allows you to do. As the game progresses, players will have access to more powerful cards, and they will have to decide which ones to purchase and which ones to pass on. In the end, players should aim at customizing their decks to fit their goals.

Players are limited in what they can do in every turn by the cards in their hand, but in Imperial Fever it was the players themselves that selected their current hand, so their actions depend on their decisions. Ultimately, a player’s pool of cards is also dependent on the decisions they made about buying and trashing cards. A good game should not allow players to do all they want but should force them to make choices. A player’s strategy is defined by the way they adjust these choices to their goals.

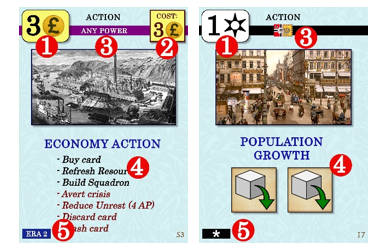

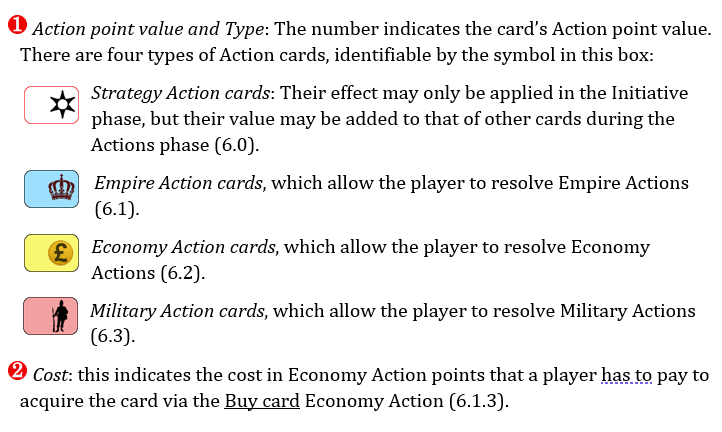

Grant: What are the four different types of cards? What is each of their functions?

Carlos: There are four kinds of cards: Strategy Cards, Empire Action Cards, Military Action Cards and Economy Action Cards. One innovation of Imperial Fever with respect to Time of Crisis is Strategy Cards. To start with, each Strategy Card is exclusive to a Main Power, so they can only be purchased by that Main Power. During play, Strategy Cards have two uses. If they are played in the Initiative Phase to determine Turn Order, players get to apply their special effect, which is exclusive to that card and suited to the Powers’ goals or strengths. During the Action Phase, players cannot activate the effects of their Strategy Cards, but they can use them as wildcards to add their value of that of the other three types of cards, which allows them to afford expensive actions even if they were not able to purchase Action Cards of the required type.

Empire Action Cards allow players to open new colonies, control Key Areas and improve diplomatic relations. Military Action Cards allow players to expand their army, gain control of open colonies and wage wars with Minor Powers. Finally, players use Economy Action Cards to purchase new Action Cards, build Naval Squadrons and refresh Resources.

Resources are represented by cubes which are either available, exhausted or in the player’s Reserve. Most actions require using Resources, so players need to manage their resources carefully and keep a healthy supply of available Resources. Resources act as a constraint that forces players to pay attention to their Nation’s economy.

Grant: What is the makeup of each player’s starting deck?

Carlos: Each player starts with eight cards, two of every type: two Strategy Cards, two Empire Action Cards, two Military Action Cards and two Economy Action Cards. All of a player’s initial cards except one are 1-value. The one 2-value card in each deck is of a different kind. There is a 2-value Strategy Card for the UK, a 2-value Empire Action Card for France, a 2-value Military Action Card for the Central Empires and a 2-value Economy Action Card for the Emergent Powers. This makes every initial deck slightly different and plays into the historical strengths of the Powers: versatility and overall supremacy for the UK, colonial ambitions for France, military strength for the Central Empires and economic dynamism for the Emergent Powers.

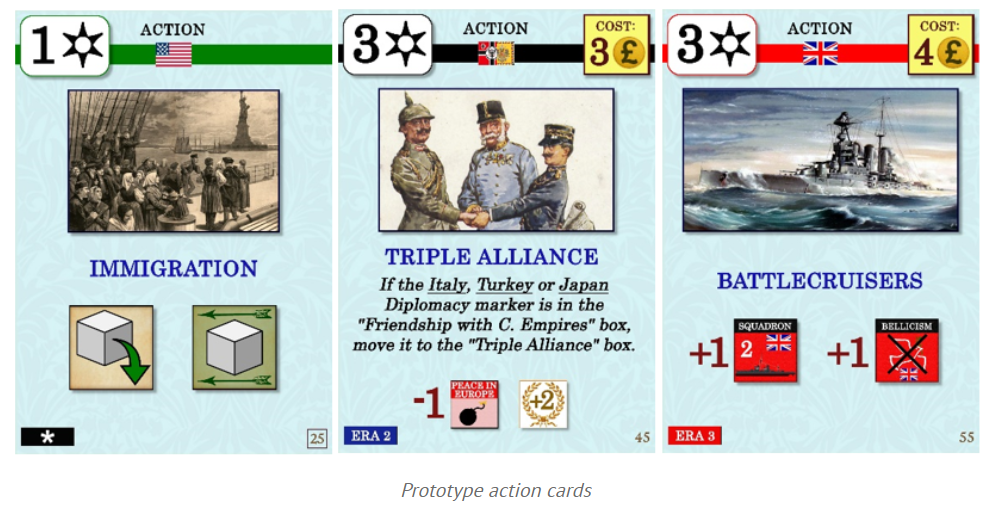

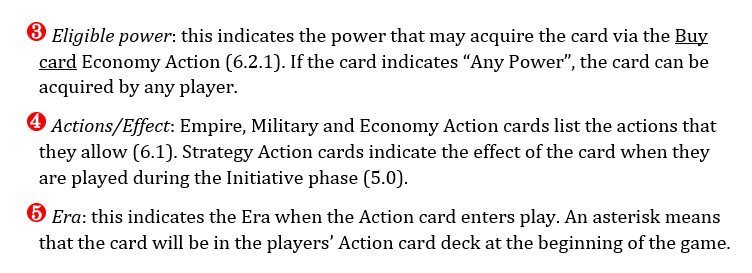

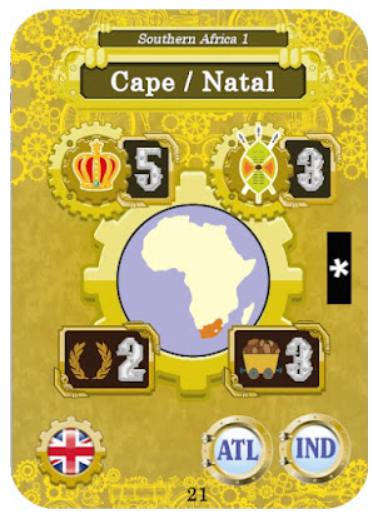

Grant: Can you share a few examples of these cards?

Carlos: Of course, here you have an example of an Economy Action Card that can be purchased by any player and a Strategy Action Card that can only be purchased by the Central Empires.

Grant: What is the Offer Display? How do players buy cards from the display?

Carlos: The game is divided into three Eras. There is a deck for each era which includes new, more powerful Action Cards, Colony Cards and War Cards. The Offer Display always shows five cards, which are the only ones that players can purchase. Every time a card from the Offer Display is taken by a player it is replaced by a new card from the deck. At the end of every turn a new card is added to the Offer Display and the other cards in the Display are moved one space to the right. The rightmost card is not removed from the game, but it is moved to the Offer Discard Pile. Players can

still purchase cards in the Discard Pile, albeit at the cost of exhausting one Resource cube.

Each Era ends when its Deck runs out. The game ends when the deck from the third Era runs out, although it may end before that if WWI breaks out. The Action Deck randomizes the availability of Colonies and the appearance of new Action Cards, which adds replayability and uncertainty to the game. It is also thematic because new Colonies were often opened by free agents without support or sanction from their governments and it was only later when those governments had to step in to establish the Colonies, usually by force.

Grant: Why is bidding for Initiative so important to the design?

Carlos: Turn Order is determined in the Initiative Phase and it may change every turn. Players bid for the Initiative by playing one of the cards in their hand. Turn Order is determined by the value of the cards played. If there is a tie, it is broken by using the default Turn Order: The UK, France, the Central Empires and the Emergent Powers. This default Turn Order reflects the different factions’ capabilities to project power worldwide. Once Turn Order is determined, the powers who played

a Strategy Card can apply its effects in Turn Order and then must discard it. Other Action Cards played in the Initiative Phase are discarded without effect. Turn Order may be important when players compete to be the first to establish a Colony, or if they are very interested in a powerful Action Card in the Offer Display. It can also be very important when there are very few cards left in the Main Deck because this means that the end of an Era or the end of the game can be triggered in the current round. Prestige is awarded for control of Naval Zones and Key Areas at the end of each Era, so players may want the Era to end when they are in control of those spaces or may be interested in acting before the Era ends to gain control of Naval Zones or Key Areas.

Obviously, players in the lead will also want to end the game as soon as possible, whereas those lagging behind will want to squeeze in one more turn before the game ends. By letting players determine Turn Order, the design adds an extra layer of decisions when selecting their hand and when choosing the card to play during the Initiative phase. As I said before, I firmly believe that good design should leave as many decisions as possible in the hands of the players. Randomizing elements of the game or resorting to fixed arrangements is always easier and gives control to the designer, but the result is that players are cheated out of decisions.

Grant: How is the Action Phase handled?

Carlos: This is pretty straightforward. Following the Turn Order determined in the previous Initiative Phase, players will take turns performing one action. In order to perform an action, players must pay for its cost with one or more cards of the appropriate type. Players may include one (and only one) Strategy Card to help pay for the cost of the action, but at least one Action Card of the appropriate type must be used. Actions also require player to use, exhaust or expend Resource cubes. As the game progresses, players will purchase more powerful cards, but the costs of the actions will also increase. With five cards available each turn, players will probably conduct between two and four actions in a Turn. Players can also trash cards from their hands by exhausting Resources or discard cards to refresh Resources or move Squadrons from one Naval Zone to another, at the cost of one discarded card for every Squadron moved.

I find that this choice to base player turns on single actions rather than players playing their whole hands streamlines gameplay. Since player turns are much shorter, downtime is minimal and players are constantly engaged in what the others are doing and adapting or reacting to their actions. This increases interaction and tension in the game, which is always a good thing. Once players have played all their hands, they refill them simultaneously, which also reduces downtime, then they perform any actions required in the Upkeep Phase and finally proceed to the End of Turn Phase, where they will check for Minor Power Actions, resolve one Event Card and advance the Card Offer.

Grant: How important are things like founding colonies and controlling regions?

Carlos: Key Areas are exclusive to each Power: only the UK can control India, only the Central Empires can control the Balkans, only Japan can control Korea and only the US can control America. All the players may try to control China. Control of these Areas is rarely safe, since Russia will interfere in Korea, the Balkans and India, and many things can happen in China. Events can also interfere with control of Key Areas. Additionally, in order to fully control a Key Area, players must win a war: the Spanish-American War for America, the Anglo-Afghan War for India, the Russo-

Japanese War for Korea and the Austro-Serbian War for the Balkans. Two other wars help France and Japan to control China: the Sino-French War and the Sino-Japanese War.

Key Areas and wars are an important source of Victory Points, especially for the Emergent Powers, but they require constant investment, both in resources and actions. Wars also require long-term planning. Colonies in Africa can only be established by the UK, France and the Central Empires. The Emergent Powers can only establish colonies in the Pacific, where they will compete with the rest of players. The number of colonies controlled by the players is one of the Victory parameters at the end of the game. Apart from these bonuses at the end of the game, colonies award prestige and allow players to open Naval Bases. This will allow them to compete for control of those Naval Zones

by building Squadrons in them. Finally, a new colony will grant its owner a number of resources that they can use in different ways:

- Invest in the Colony, by spending resources rather than extracting them. This grants Prestige to the player.

- Exploit Resources, which will refresh a number of cubes in the player’s Board equal to the Colony’s Resource Value.

- Plunder Resources: This moves a number of cubes equal to the Colony’s Resource Value from the Reserve to the player’s Board. This reduces the player’s Prestige.

The number of established Colonies and the degree of control of Key Areas are two of the sources of Prestige Points during the game and Victory Points at the end of the game, but Victory Points are also scored by the control of Naval Zones, Army and Navy size and National Prestige. Establishing colonies is an important stepping stone for victory, but no player will win if they focus exclusively on establishing the most colonies. This is a game of competition, so players should not overinvest in

any one parameter: controlling one more colony than the rest of the players will do just as well as controlling twice as many colonies.

Grant: How do you model the influence of non-player powers?

Carlos: Non-player Powers are referred to as Minor Powers in the game, although some of them hardly fit the label. At the end of every turn, players must roll 2D6 and check the result in the Minor Powers Table. The effects may vary: If the result is “Russia”, 1D6 die is rolled and the result indicates which Key Area is affected: India, the Balkans or Korea. The owning player must exhaust

one Resource cube from that Area, thus reducing their control of it. Some Colony Cards include the flags of the Minor Power that historically had interests in them. If the result of the Minor Power roll is “Colonial expansion”, one of these Minor Powers will open one such Colony or establish an open Colony where they have an interest, even if opened by a Major Power. This may lead to diplomatic conflicts which must be solved by creating a Condominium, which is not so advantageous for the Main Power, or by increasing diplomatic tension with the Minor Power. When opening a Colony with a Minor Power flag, players should be aware that this may lead to a conflict with that Power.

Some results in the Minor Power table affect China. They may imply exhausting Major Power cubes from the China Box, which represents intrigues and revolts, or China granting concession to the Major Powers with cubes in the Area, which adds Prestige to those Powers and lets them refresh Resource cubes. However, after a concession is granted, all cubes in the China Box are exhausted (except those in War Boxes) and players must rebuild their influence there.

Apart from the Minor Power roll, Russia, Italy and Turkey may enter in an alliance with France or Germany. Russia may join the French-led Entente and Turkey and Italy may join the Central Empires in the Triple Alliance. Italy and Turkey have Naval Squadrons that may help the Central Empires control the Mediterranean and armies that will contribute to the Triple Alliance’s military power. On the other hand, should Russia throw their lot with France, Russia’s huge army may tilt the

balance of military power in Europe. Additionally, although a Major Power, the UK may also join France in the Entente, and this will let them pool their military resources and thus help them control Naval Zones together. Finally, some Events also represent the actions of Minor Powers, like the Turkish-Italian War, the Boxer Rebellion, or the assassination of France Ferdinand.

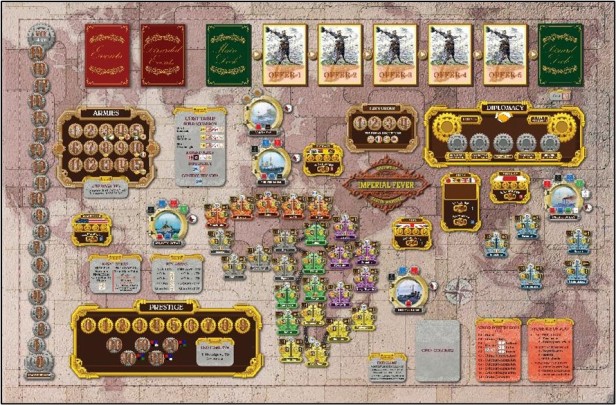

Grant: What is the layout and makeup of the game board?

Carlos: The spaces included in the map can be divided into three categories: Colonies, Key Areas and Naval Zones. There are 30 Colonies on the board, divided into six regions of five Colonies each, five of them in Africa and the remaining five in the Pacific. The space for each Colony indicates the Naval Zones it is adjacent to, as well as its connections to sea lanes and other colonies. Each Colony Space also indicates the cost in Empire Action Points that are required to open the Colony and the number of defence dice that will be rolled to represent native forces opposed to the establishment of the Colony. The Colony Space includes the Prestige bonus gained by the Major Power that manages to establish it and the Resource points they will have at their disposal. If a Minor Power has interests in the Colony, its flag will also be displayed in its space.

Each Key Area indicates the Major Power(s) that can interact with it. The upper half of the Balkans, India, Korea and America Key Areas have boxes for four Resource cubes, which the relevant players can place there using Empire Actions. The fifth box in the lower half of each Key Area can only be filled with a cube if the Major Power wins the war associated with it. The name of the war and the Era when the corresponding War card enters play is indicated in the box. The cubes in the upper half can be exhausted as a result of Russia’s actions during the Minor Power segment or as a result of an Event. Cubes placed in War Boxes are never lost or exhausted. There is no limit to the number of cubes that can be placed in the upper half of the China Box. The lower half includes two War Boxes, the Sino-French War and the Sino-Japanese War.

The board also includes tracks to record the Prestige and Armies of each Major Power, a Diplomacy Track to indicate international relations, and a Turn Order Track where the playing order for each turn is reflected. A Peace in Europe Track measures European tensions, which may lead to the outbreak of WWI and trigger the end of the game. The board also includes slots for the Main Deck, the Card Offer Display and the Offer Discard pile, as well as Event Cards, discarded Event Cards and Open Colonies. Finally, there are several Play Aids detailing the cost of various actions, the various

Prestige bonuses awarded in New Era Phases and the Victory Points awarded at the end of the game.

Grant: How is victory achieved?

Carlos: The winner of the game is the player that accumulates most Victory Points at the end of the game. These Victory Points come from seven different sources:

- Prestige: Prestige is converted to VP’s at a 2:1 ratio, rounding up. Prestige is gained throughout the game by expanding the army, building Naval squadrons, establishing Colonies, controlling Key Areas and Naval Zones and by winning Wars, and occasionally through Events and Strategy Cards.

- Colonies: The player with most Colonies is awarded 5 VP, the player who has the second most Colonies is awarded 3 VP and the player who has the third most Colonies is awarded 1 VP. Additionally, each player is granted 1 VP for each Region where they have established at least 3 Colonies.

- Key Areas: Players are awarded between 3 and 1 VP for each Key Area with their flag, depending on the number of Resource cubes they have there. Players lose 2 VP for each exclusive Key Area where they have fewer than 3 cubes.

- Army size: the player with the highest Army Value is awarded 5 VP, the player who has the second highest Army Value is awarded 3 VP and the player who has the third highest Army Value is awarded 1 VP.

- Fleet size: the player with the highest Fleet Value is awarded 5 VP, the player who has the second highest Fleet Value is awarded 3 VP and the player with the third highest Fleet Value is awarded 1 VP.

- Control of Naval Zones: Each Naval Zone controlled by a Main Power or a Coalition grants 1 VP to its owner. Every member of a coalition with a Naval squadron in a Naval Zone will get the VP for controlling it.

- Agenda Cards: One Agenda Card is chosen by every player at the beginning of the second and third Eras. These Agenda Cards grant between 3 and 5 VP depending on specific objectives. Some of these cards will fit the strengths of some powers better than others, but they can be chosen freely and they help players focus on a strategy.

- It must be clarified that if there is a tie, all tied players are awarded the VP granted by their position.

- Finally, there is a 4 VP Penalty for the player who ended the game by reaching 20 points of Bellicism and thus triggering WWI, if that was the case. Any player whose Bellicism Value is higher than the value of European Peace loses 2 VP’s, and any player whose Bellicism Value equal to the value of European Peace loses 1 VP’s.

Grant: What changes have come about through play testing?

Carlos: The game has evolved thanks to the feedback from play testers and to the evidence gathered from the many games that have been played online and face to face. I would say that the biggest change involves the board itself. Originally the board had no map, just slots for up to eight open colonies, where players placed Resource cubes to gain control of them and Key Areas and Naval Zones were grouped together without taking not account their geographical location. Then a good

friend, Adolfo Suárez Jimeno, suggested that the board could be organized around a map. I was not sure it would be possible, but he insisted and of course he was right! Despite my initial misgivings, he created the wonderful board that we are using for playtesting and I hope will go on to become the final art for the game. It turned out that not only was it possible to create a board around a map that included all the Colonies and Naval Zones in their proper place, but it was much better than the

original, more abstract board. Firstly, any board with a map is better, but, more importantly, the new design has improved playability, has helped visualize connections between Colonies and Naval Zones and includes much more information without feeling too cluttered. I am deeply indebted to Adolfo for his insight and for all the work he put in his first-rate design. Incidentally, the Colony cards are also his design, as you can see when comparing them with the rest of the cards, which are my own poor work.

As to gameplay, in the original design players had to play all their cards in their turns, which made the game slower and generated a lot of downtime, even though everything connected to Colony creation was moved to the end of the turn to reduce that downtime. The change to a system where players take turns performing single actions has greatly increased interaction and reduced downtime. It has also allowed to move Colony creation to the player Action Phase, which also

streamlines the game.

Other changes have led to integrating the various game systems, which initially felt somewhat disconnected. Thus, with the new rules increasing Prestige generates resources, expanding the army grants Diplomatic Actions and establishing Colonies creates Naval Bases that generate resources and allow players to attempt to control Naval Zones they had no access to at the beginning of the game.

Finally, I am still working on tweaking Prestige Points and Victory Points to balance the game, though results from playtesting seem to indicate we are getting close to getting as much balance as we can aspire to. In a game as asymmetrical as this, with so much interaction and so many strategies open to players, it is up to the players themselves to balance the game, and they can do this by choosing strategies that play into their strengths and adapt to the choices of the other players. I find that no two games of Imperial Fever are the same, and a change in strategy by one of the players alters the strategic options for the rest of the players. For instance, usually it is in the UK’s interest to control as many Naval Zones as possible, since it plays into the UK’s strengths. However, if the UK player decides to follow a different path to victory, this will leave control of the seas open to the other players, which would be much more difficult if the UK adheres to its

historical strategy. It is the way the other players take advantage from this void in naval power that will eventually define the balance of the game.

Grant: What do you feel the game design excels at?

Carlos: As the designer of Imperial Fever, I feel more than reasonably satisfied with the game, so I am not the most objective person to answer this question, but I will do my best. When I evaluate a game of historical simulation, I ask myself two questions: Does the game develop a historically plausible narrative? and Is the game fun?

To answer the first question, I believe that Imperial Fever is true to its theme. Power asymmetry, strategic goals, events and the very flow of the game are designed to replicate historical processes, although naturally the development of the game may deviate from history depending on the players’ choices. I am confident, however, that whatever happens during a game is something that could

have happened historically.

To answer the second question, whether a game is fun or not depends very much on the players’ tastes. To concentrate on a single aspect, I personally find tension and unpredictability fun, and I believe that both are connected. By uncertainty I mean devising a plan and then having other players or events possibly interfere with it. By tension I mean that feeling when you are trying to

carry out your plan but you know it can go astray if any number of things beyond your control happen: another player purchasing the card you need, the era coming to a close before you have been able to win your war, an event increasing your unrest, another player taking the Colony you needed to open a Naval Base in the Indian Ocean, etc. From this point of view, the game is fun.

As I mentioned at the beginning, one of my design goals was to create a game which generated sensations like those of the old Pax Britannica, but without its fiddleiness, bookkeeping, balance issues and duration. I would like to think I have succeeded. Actually, one of the things I am most happy about is that the game can be played to completion in under four hours, provided reasonable familiarity with the system. Also, although the system may seem a bit daunting at the beginning, with many things to do and many strategic options on the board, its various elements click into place and players start to devise long- and medium-term plans and goals after a couple of Turns.

Grant: What other designs are you currently working on?

Carlos: Playing and designing games is a hobby for me, not a profession, although I approach it with the same seriousness and thoroughness that I apply to my career as a linguist and a teacher. However, I do have a job and a wonderful family to attend to and right now, my hands are full with the final touches to The Other Side of the Hill, which are more time demanding than I would have expected. As soon as it goes into production, I intend to step up playtesting for Imperial Fever and create more promotional material about it to try and push it over the 500-pledge mark. Of course, I have other ideas, as well as other games in an advanced stage of development. And not all of them are games of historical simulation: I have a zombie game that I think is fun, and a couple of designs based on Tolkien’s world, should any company be interested 😉

As to other historical games on my design board, many players are demanding an adaptation of the system used in The Other Side of the Hill to other sides and/or theatres of WWII, as well as to other conflicts. I have some ideas, but they are still very vague, so I will not commit myself to anything yet, especially because I enjoy variety and, right now, I think I would prefer a change. In fact, I have also been thinking about a game set in the time before the events of Imperial Fever, and I feel very attracted to that idea. We shall see.

Before I finish, I want to thank you for this opportunity and the job you do helping designers of games of historical simulation. You are very detailed and thorough in your questions and they have helped me to verbalize much of the design philosophy behind Imperial Fever and, if the interest of the game could be measured by the length of this interview, it would be a very interesting system indeed!

Thank you so much for your time in answering our questions Carlos. I know you are busy, with many different commitments, but I think that this interview will give some prospective buys plenty of information to sink their teeth into and allow them to make a more informed decision.

If you are interested in Imperial Fever: Great Power Competition in the Late 19th Century, you can pre-order a copy for $58.00 from the GMT Games website at the following link: https://www.gmtgames.com/p-1050-imperial-fever-great-power-competition-in-the-late-19th-century.aspx

-Grant