Legion Wargames always looks for ungamed subjects and a few months ago I cam across one of their newest offerings covering the Southern Theater of the Latin American Wars for Independence from 1809-1824 called Libertadores del Sur. Almost immediately the designers reached out to me wanting to do an interview and it was very refreshing to not have to chase them down so I was able to get this to them pretty quickly and get it ready to post. There are 3 respondents to the interview including the design trio of Keith Hafner, Matt Shirley and Juan Carballal.

*Please keep in mind that the artwork and layout of the components used in this interview, including cards and the board are not yet finalized and are only for playtest purposes at this point. Also, as this game is still in development, rule details may still change prior to publication.

Grant: First off Keith, Juan and Matt please tell us a little about yourselves. What are your hobbies? What’s your day jobs?

Keith: I am a retired U.S. Army Latin America Foreign Area Officer who has both lived and travelled extensively throughout Latin America. I speak Spanish and Portuguese and enjoy reading military history, painting, and running. I have had a lifelong interest in board wargaming which started with the Europa Series of games covering World War II in Europe at the division level. This hobby clearly helped with my military career, and I was fortunate enough to be able to visit some of the battlefield sites that are covered in Libertadores Del Sur. I currently work and reside in Europe as a Federal civilian employee.

Matt: I’m a retired Fed with 20 years active duty as a U.S. Navy JAGC Officer (attorney) and 11 in the Inspector General field. I graduated from the Naval War College, which was getting paid (!) to pursue my hobby of military history and board gaming. I’ve been playing games with toy soldiers and/or modeling warfare since I was as young as I can remember, and I discovered Avalon Hill in 1974. In addition to board games, I also do gaming with miniatures, and have run several events at various gaming conventions. In addition to that, I participate in competitive swimming with U.S. Masters Swimming, and my retirement gig is a part-time swim coach.

Juan: I am from Buenos Aires, Argentina. I work with the Interamerican Development Bank in sovereign loans for procurement of public works, so I sort of deal with complex rulebooks daily. I have designed, reviewed, play tested, developed, and published many boardgames, and used to be a games retailer. My long history with modern boardgames started 30 years ago with some great Avalon Hill titles, especially History of the World (not the brief one), and Dragon Quest (a tabletop version of First Edition D&D).

Grant: What motivated you to break into game design? What have you enjoyed most about the experience thus far?

Keith: I have been interested in wargaming and strategy games since my childhood and I figured that it would be interesting and fun to design a game covering the Latin American Wars for Independence because it was such an obscure and relatively unexplored topic in modern board wargaming. I have enjoyed the military history research and sense of accomplishment that comes with creating something from scratch. It is interesting to me to see how playability interacts with historical accuracy and how to model the tradeoff between these two concepts. One of the more challenging aspects of this project has been trying to model the Napoleonic era into a vastly different geographic setting, with armies and units much smaller than their European contemporaries.

Matt: I enjoy teaching a game to new players almost as much as playing it myself. The miniature games I run at conventions use rules sets that my friends and I have created, and that’s how I started. I met one of my dearest friends while at the War College, Lance McMillan (yes, the Lance McMillan from Victory Point Games), and he got me into playtesting various VPG games. That got me interested in what kind of game mechanics work well in combination with others, and model well certain situations. I think what I enjoy and do best is identifying situations where two different sections of rules interact, and clarifying how that is resolved. Sometimes, I can drive other people working on a project a little nuts because they come up with a big idea, and they see clearly how it is

supposed to work, while I’m off to the side asking them how that affects the logistics rules.

Juan: I’ve been designing games before I knew I was doing it. Back when videogames came in BASIC language books and you had to type it in an Apple II to make them work. Of course, you then proceeded to tweak them to your liking. Discovering role playing games was the second big leap. I’ve been mastering and homebrewing campaigns since I was as old as the kids from Stranger Things. Since the Eurogame craze arrived late in Argentina, I gained many friends introducing them to print and play versions, vassal modules, my own prototypes, and the odd original I managed to acquire from someone traveling abroad.

Grant: What different strengths do each of you bring to the design process?

Keith: I bring the detailed military historical knowledge of the Latin American Wars for Independence. This has helped with developing order of battle, uniforms, and trying to come up with accurate command rating for various leaders during the development and design process. I have tried to help with keeping some of the more unique aspects of the design process true to historic form, such as arguing over the color of Portuguese imperial uniforms while on campaign or accurately modeling terrain effects of the second highest mountain chain in the world.

Matt: I have lots of experience playing numerous kinds of games, and I can see several different ways to get the results we want. I have a good grasp of probability (my Bachelor’s is in Mathematics), and can streamline processes for random results. And of course, my talent for asking pain in the … neck questions described above.

Juan: I have a good eye to recognize the potential of a great game concept, and the experience to traverse the long and hard journey from a prototype to a published product. Moreover, being a local from Argentina and a Spanish native speaker, has allowed us to contact play testers, artists, publishers and cultural institutions from Argentina and Spain, whose insight has greatly enhanced the overall scope and perspective of the game.

Grant: What is your upcoming game Libertadores del Sur about?

Keith: Libertadores del Sur is a two-player military simulation wargame of the Southern Theater of the Latin

American Wars for Independence. The Patriot player controls the Argentine Ruling Directory forces and various federated and allied forces, while the Royalist player controls Spanish Regular Army, trained Loyalist South American forces, and militia units. Several other historical armed factions contend for each player’s attention when formulating strategy, from a land grabbing Portuguese-Brazilian Imperialist army, local guerrilla units, breakaway Federal Republics, and rebellion in the Andes Highlands.

Juan: Libertadores del Sur is about the great figures of the South American history. Patriots in this game are the Founding Fathers of today’s nations. Spanish Viceroys were rulers of huge and populous kingdoms. The Portuguese ruled a land in the Americas that even today is one of the largest nations in the World. Imagine a world where there are no military strategy games about General George Washington! This is where we are for the great Liberators of South America. There must be a game that tells their history in the proper depth and detail. This is that game.

Grant: Why was this a subject that drew your interest?

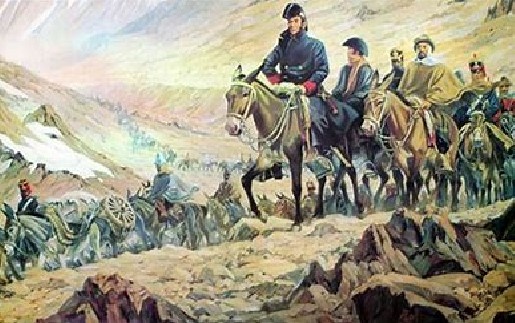

Keith: While traveling, reading, and walking over the South American battlefields of General San Martin in Argentina and Chile and General Simon Bolivar’s in Colombia, I was struck by the incongruity between the epic nature these Liberator’s achievements, juxtaposed with their largely overlooked status in the annals of military history. The actual idea for creating a wargame out of Latin America’s struggles for independence first came to me in 2006, when I was following in the path of Argentine General José de San Martín and his legendary Army of the Andes’ trek over the Andes Mountains in 2006. The sheer scale and majesty of those mountains deeply impressed upon me what San Martin accomplished from a military-logistical perspective in crossing an army over them. So, part of the appeal of working on this project is that it is a topic that has largely been ignored by the wargaming community. The holy trinity of wargaming (WWII, American Civil War, and Napoleonic Wars) saturate the wargame market, so I thought presenting a spin-off of the Napoleonic Wars, that is almost unknown outside Latin America would be both fun and interesting. San Martin’s liberation of Chile was a breath-taking military achievement that easily ranks alongside Hannibal’s crossing of the Alps in terms of its audacity. Outside of Latin America, however, General San Martin’s name and his military exploits are almost unknown. South America’s relative geographic isolation from the rest of the world, I believe partially accounts for the relative obscurity of this topic in military history. But I think South America is almost a tabula rasa, when it comes to

military history from a larger world perspective, so helping to tell this story interested me greatly. We already have a translation of the rules in Spanish.

Matt: You can blame Keith. (Most people do; just ask his wife.) My knowledge of the Latin American Wars of Liberation pretty much ended with having vaguely heard of Simon Bolivar. Then Keith mentioned he wanted to do a game about them and lent me his book, Libertadores by Robert Harvey. I was amazed by both the history of the era, and my own ignorance of it. (To be clear, Harvey’s account plays up the sensational aspects of the story.) I agreed instantly we must do a game on the subject.

Grant: What research did you do to get the details correct? What one must read source would you recommend?

Keith: I have two master’s Degrees in Latin American Area Studies and Military History, so I already had a very extensive library and background knowledge on the subject matter in addition to having travelled, lived, and worked in South America and Spain. I also speak Spanish and Portuguese which helps for original research. I would recommend War and Independence in Spanish America by Anthony McFarlane. It is, in my opinion, one of the most comprehensive single volume books in English on the subject.

Matt: This is my recommendation for people who know little if anything about the Latin American Wars of Liberation. If you like to read your history, the Libertadores book mentioned above will fire your imagination. If you prefer to listen to your history, I recommend the podcast by Mike Duncan, Revolutions, specifically the series on South American liberation at: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish_American_wars_of_independence

Juan: I have travelled along every connection and visited every city in the map, but three of them. Does that count? I totally recommend the touristic approach! 😀

Grant: What from the historical period of the Latin American Wars for Independence is most important to model?

Keith: Spanish military weakness. The Spanish Royalist player must conquer Buenos Aires as soon as possible. A proposition that the British Army learned to their ignominy in 1806-1807 is not such an easy military feat. Argentina was the Patriot movement’s strategic center of gravity and the military catalyst for independence in South America. In 1816, the United Provinces declared independence under the political leadership of Buenos Aires. The existence of such a vast sanctuary state for military action against the Spanish empire proved fatal to Royalist ambitions to reconquer the empire. From 1810-1818, Patriot Argentina repeatedly acted as a strategic military springboard for

multiple invasions against Spanish power in Uruguay, Paraguay, Chile, Bolivia, and ultimately the royalist center of gravity in South America, Peru.

Spain’s strategic inability to successfully reconquer and pacify any part of the United Provinces throughout the entire war, demonstrated the limits and inherent weakness of Spanish military power. From 1810-1817, Spanish military strategy aimed at reconquering Argentina by marching from upper Peru (Bolivia) across the continent to approach Buenos Aires from the west. All four of these abortive of invasions into northern Argentina failed due to overextended supply lines, guerilla harassment, and lack of even minimally adequate Spanish military forces. In short, Spanish strategic military efforts to reconquer the Rio de La Plata from the Viceroyalty of Peru were entirely

unrealistic from both a logistical and manpower perspective. Napoleon’s invasion of Spain in 1808 along with the destruction of her navy at the Battles of Cape Saint Vincent in 1797 and Trafalgar in 1805, resulted in the unravelling of effective Spanish military control of her empire in the Americas. From 1808-1824, Spain was forced to fight in three overseas strategic theaters simultaneously (Peru-

Argentina, Venezuela-Colombia, and Mexico) with extremely limited military and economic means, while facing the ideological backing for decolonization and colonial free trade from the superpower of the day, Great Britain.

The Peninsula War forced the Spanish Empire into a Faustian bargain of needing British military power against Napoleon in Europe, at the price of undermining its own imperial political and economic legitimacy through British free trade with its Latin American colonies.

Matt: There are two aspects. First, the distances the armies had to cross were vast, and the terrain in those areas was extremely challenging. Keith points out that in terms of elevation and ruggedness the Andes are comparable to the Himalayas. We wanted the players wrestling with the logistics of getting to the fight and the need to assert political control over newly entered provinces. Second, the politics of who was fighting who were wild. The factions we have called “Federalists” wanted independence not only from Spain, but also from the government in Buenos Aires (the “Patriots” in game terms), and those two factions fought each other as hard as they fought the Royalist armies. In addition, Portuguese Imperialist forces invaded the area that is now Uruguay (Banda Oriental

in the game), hoping to seize territory amid all the confusion. We wanted the game to reflect the turbulent politics of the conflict.

Grant: What is the scale of the game and the force structure of units?

Matt: Units are portrayed by single counters and represent a battalion of troops, a battery of guns, a cavalry regiment or caravan of supplies wagons. Each counter represents approximately 400-800 men and equipment. Game rounds represent one year comprising the operations of both sides, which are represented by the playing of their game cards allowed by their side’s Political Will. Turns are portrayed by each side playing a card, and each card represents approximately two months.

Grant: What different units are represented in the game and what advantages do they bring to the battlefield?

Matt: There are five kinds of combat units, and Leaders. Line infantry units are the most numerous, and they generally have the highest combat factors. Light Infantry units are immune from artillery fire, and they improve the chances of a flanking force participating in the battle. Cavalry units can pursue and cause casualties to a force retreating from a battle. Artillery units fire twice during a round of battle, and they can pick their targets. Militia units are weak infantry units that “pop up” with the play of an event card, sometimes right before a battle.

Leader units represent named Commanders from the period. They are necessary if during your turn you want to activate and move forces that have more than a single combat unit. Also, they can Rally back to full strength combat units that have been disordered during a battle.

Grant: Who are the different playable factions?

Keith: The following is a rundown of the different factions:

a) Latin American Patriot Forces: Argentine, Chilean, Banda Oriental (Uruguay), Alto Peru (Bolivia)

b) Latin American Federal & Non-Aligned factions: Paraguay, Argentine & Chilean Federal Provinces, Banda Oriental (Uruguay), Alto Peru (Bolivia)

c) Royalist Forces: Spanish Peninsular Regulars & Latin American Loyalists, & Portuguese/Brazilian Imperialist

Grant: As a card driven game, how are cards used in the design?

Matt: Each side has its own set of two decks of cards. One of the decks is a set of Year Event cards. They are unique to each side, representing significant historical events. Each player can play one of the cards available that year at the start of the round; think of them as headline events. See below for examples. The other deck is a set of Operational cards. As is traditional in Card Driven Games, they have an operational value and an event/battle effect. They player can play an Operations card for its operational value to active and move a force, or play it for its event effect. Some cards have battle or reaction effects which are played at the start of a battle.

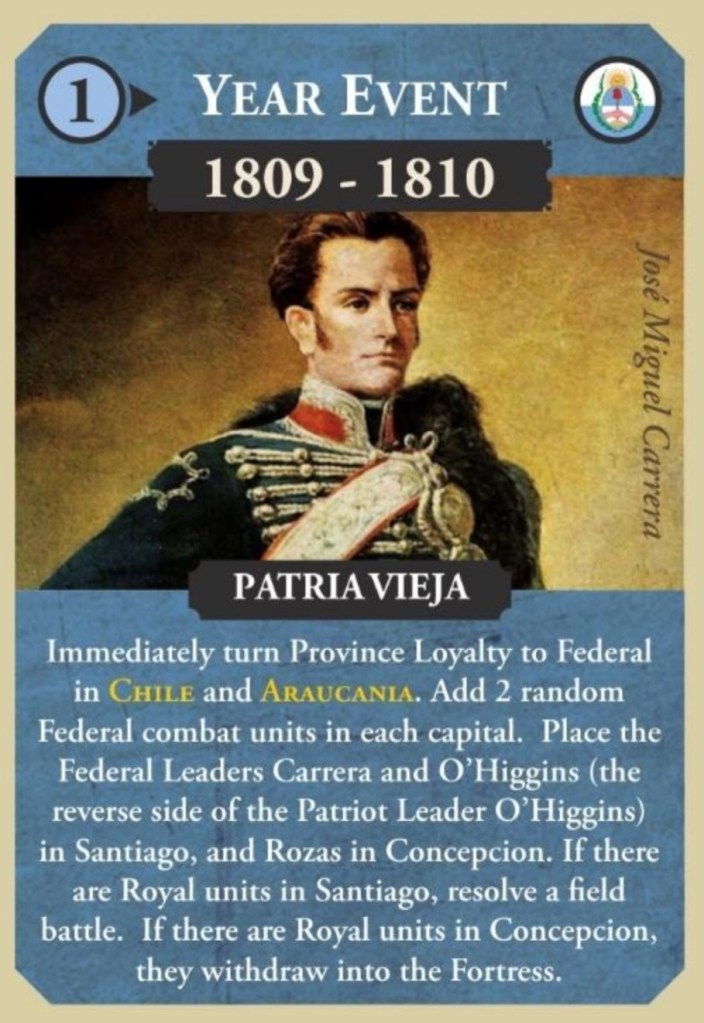

Grant: What is the anatomy of these cards?

Matt: The Patriot player can play the card on the left at the start of a year/round. The light blue color and the flag icon in the upper right show that it’s a Patriot card. The date range “1809-1810” means it is available for the 1809 or 1810 round. The portrait of José Carrera and the title “Patria Vieja” are historical flavor. The text below the title describes its effect. There is an operational value of 1 shown in the upper left. If a player doesn’t like any of the Year Events available, one of the Year Events cards can be played for this (de minimus) operational value as if it were an Operations card.

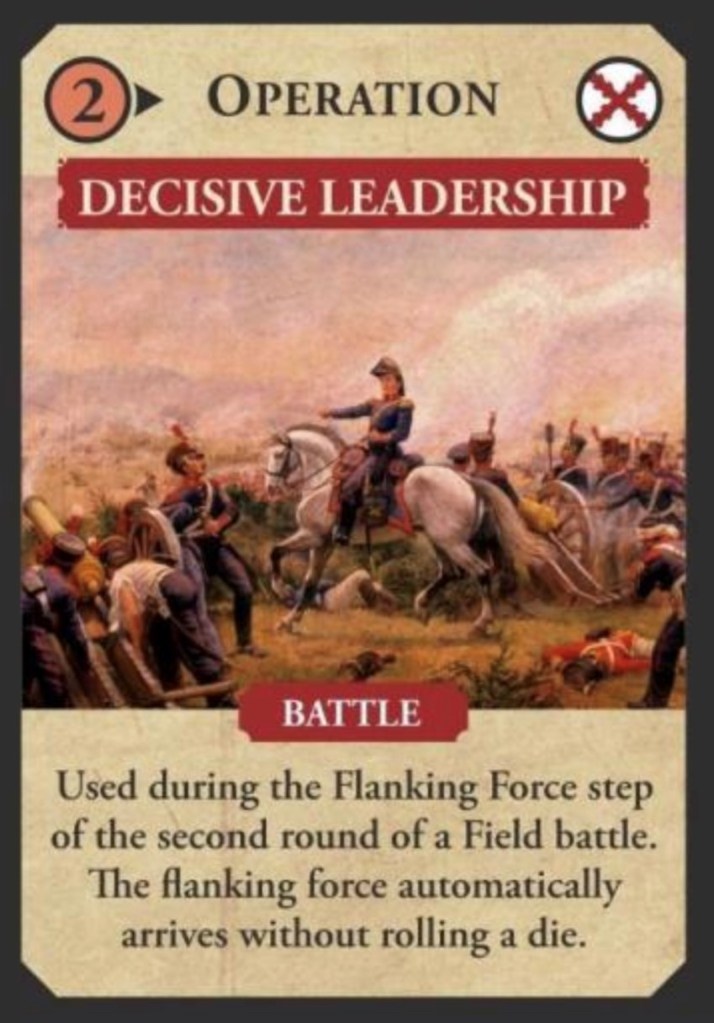

The Royalist player can play the card shown on the right at the start of the Royalist turn. The red color and the flag icon

in the upper right show that it’s a Royalist card. This would be for its operational value of 2, which is used to activate a force—a Leader and his subordinate combat units—to move it, and possibly trigger a battle at the end of the move. Alternately, the card has a battle effect; the word “Battle” below the illustration shows this. Operations cards will have one of the following types: event, battle, or reaction. A player can use the card for its effect at the appropriate point in the round instead of for its operational value. The title “Decisive Leadership” and the illustration are historical flavor. The text below the illustration describes its effect.

Grant: Does each player have their own deck or share a common deck?

Matt: Each side has its own set of two decks of cards. The Year Event cards are unique. The Operations decks are functionally identical; some of the cards are tweaked to reflect each side’s situation.

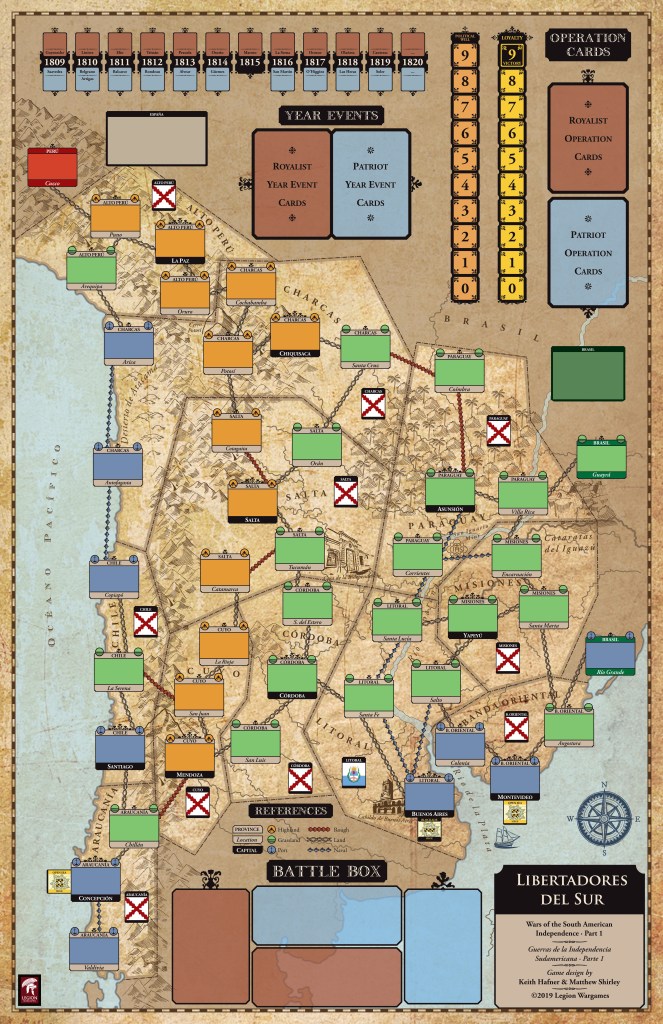

Grant: What area does the board cover? How does it show such a large geographic area?

Matt: The map shows the geographic areas consisting of modern-day Uruguay, Paraguay, Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile; but as it was in 1809-1820. As is traditional for Card Driven Games, it uses a Point-to-Point Movement system, which channels movement of forces along the feasible routes of the time. There are three distinct areas. In the west in the modern-day Chile, bounded by the Atacama Desert to the north (one of the driest places on Earth). To the east are the Andes Mountains, and to the south is the howling wilderness of Patagonia. The central area is east of the Andes, but west of the Paraná River. It contains the main highway running from Buenos Aires in the south, to Lake Titicaca at the entrance to Peru in the north. Significant colonial settlements were located on this

relatively narrow strip of (barely) traversable territory in the Andes highlands. The third area is east of the Paraná River to the border with southern Brazil; it includes the area of modern Paraguay and Uruguay. The land adjacent to the Paraná River is a thick jungle, and moving between settlements on the river is difficult even using the river for transportation. The area of modern Uruguay is a plain, highly suitable for moving military forces, and quite the temptation for adventurers from Brazil.

Grant: What strategic pinch points are created by the layout of spaces on the Point-to-Point Movement board?

Juan: You have some clear axis between Buenos Aires and the cities that turned out to be the capitals of the various nations around Argentina. Like in a State of Siege game, the Royalist player will be able to advance one way or another along all of them, and the Patriot player will be measuring how far along those lines to push the Royalists back without leaving the Patriot Capital (Buenos Aires) vulnerable.

The route to the West, between Buenos Aires and Santiago de Chile has a major barrier in the Andes to serve as a hard border, and Chile is easily reinforceable for the Royalists by sea against Patriots or Federals. Completely different is the way to the North-West, where there is a long and hard slog up the mountains filled with Federals to reach Bolivia, but that is where the main Royalists forces might be coming from. Then to the North-East is Paraguay, which is a pain to get to and reinforce unless you have boats to sail up the Paraná River, and can be menaced by the Federal or Portuguese forces. Finally, to the East, a dangerously short route between Buenos Aires and Montevideo that must be kept from the Federals, the Portuguese and forces sailing from Spain. Each year, players will likely be engaged in 2, 3 or all those fronts simultaneously. Knowing where and when to push forward and where and when to give way is the key strategic decision of the operational game.

Grant: What advantage does point to point give the game?

Matt: As noted, it channels the movement of forces along the feasible routes of the time.

Juan: For once, I believe it simplifies the real options for the players. Having a hex grid with impossible movement penalties that you find out they are impossible half way through your movement is no fun. The generals of the time knew this and so should the players. The theater of operations is very sparsely populated by non-native peoples and a huge (like East Front huge) expanse of rough wildlands with minimal established roads and few navigable rivers. Even some connections the game allows through rough country will disorganize your whole force. They are like Hannibal crossing the Alps. Once a game, you may pull them off to take your opponent off balance,

as San Martin did to Santiago, Chile or Bolivar did to Bogota, Colombia but those were as far as we could realistically go.

Grant: How important is Morale to the game?

Juan: As we found out, and argued about extensively, “morale” is a tricky word. The game portrays Morale at the operational level as Political Will, that is, the will of a side to support the war effort. That is one of your main resources and it results in the number of turns you can take during a year (round). You lose battles or sieges, by yourself or controlling the Federal forces, and your side’s Political Will drops, and you can now take less turns before your year ends.

On a tactical level, Leaders can Rally back disorganized units according to their Command Rating. But playtesting has proven that positional warfare weights heavily in your decision to retreat, many times, sooner than when your troops are forced to route. This is one of the key features of the tactical game and it is simply brilliant. It is not just about raw numbers chasing dice rolls. The number and quality of your troops count as much as what tactical cards are played, an ambush, controlling the high ground, a move in the rear, there are many cards that can be very powerful if played in the right circumstances. Also, the type of troops matter, which units are placed in the center or the flank, when will the flanking forces arrive, what is strategic depth is available to withdraw to live to fight another day, is pursuing cavalry present? All these factors won’t allow you to easily put the blame for your defeat on your own soldier’s cowardice, I tell you.

Grant: What is the general Sequence of Play?

Juan: The game is played in rounds that represent a year of operations. At the start of a round, both players use a Year Event card. These cards have powerful effects that represent historical events particular to each side. During the round, players take turns successively, using cards for operational point values to activate a Leader, regroups forces, move, and attack with the forces under their command. Once you take your turn, your Political Will goes down one step. If you move to an enemy occupied location, a battle ensues. If you are fighting against a federal force, your opponent will control them. Both sides move their engaged forces to the Battle Box and using

dice and any Tactical effects of operations cards in hand to resolve combat. Whoever loses the battle, also loses a step of Political Will. Once you are out of Political Will, your round is over. Once the round for both players is over, you count which Provinces changed hands, apply siege effects, attrition effects, etc. and levy troops. The number of Provinces controlled determines the winner of the game. Each round lasts about 15 minutes. The game can last up to 10 rounds, but usually doesn’t, unless both players are really good or bad at it. Don’t worry if your first game lasts 40 minutes. It’s easy to learn, but hard to master.

Grant: How does combat work?

Matt: We described above the roles of the different kinds of combat units. When a force enters a location containing an enemy force, a battle will normally follow. The turn must end with one side in possession of the location (possibly with an enemy force besieged in one of the three fortress locations). Each side has an opportunity to play an operation card for its battle or reaction effect (possibly avoiding battle). The battle proceeds in rounds with each unit rolling for a chance to hit until one side is eliminated, or chooses to retreat. There is also a chance for each side to form a flanking force that will be quite powerful, but may or may not arrive in time to participate.

Grant: How is victory achieved?

Matt: Establishing political control over enough Provinces. The locations on the map are grouped into Provinces that roughly correspond to the historical colonial administrative regions at the time, e.g. Chile, Cordoba or Alto Peru. At the end of each year/round, the players assess which faction has political control of each Province. It is possible for either side to win the game before 1820 by controlling almost all the provinces, but that is hard to do. Most often, the player who controls more Provinces at the end of 1820 will be the winner.

Grant: How many scenarios are included?

Matt: Right now, there is the one scenario starting in 1809. We might be able to have a second, shorter scenario that starts in 1814 in time for printing. However, if anyone is looking for a historical variant scenario (magazine article?), there was a wild plot at the time to rescue Napoleon from St. Helena, and offer him command of the Patriot forces in South America. Lord Thomas Cochrane, the real-life inspiration for the character of Jack Aubrey in the Master and Commander Series of novels, was its leading advocate, Intermediaries for the government in Buenos Aires and for Napoleon did have discussions. I remain skeptical that Latin American patriots would rise in revolt from the Spanish Empire only to hand the keys over to Bonaparte, but that illustrates just how dramatic

were the politics of the era.

Grant: What are you most pleased about with the outcome of the design?

Keith: That we finally finished it. This has been a decade long struggle of passion and perseverance on the part of all involved. I think that game we have put together is a unique and historically accurate simulation of the logistical, military, and political challenges faced by both sides during the Latin American Wars. I am very proud of the work that we have done.

Matt: As we described the politics of the conflict was totally nuts. We think that the system we made for Federalist and Portuguese forces offers the players the chance to indulge in the political insanity of the period. We describe Libertadores as a two-player game portraying a three-sided conflict. The three of us used a Vassal module and Skype in share screen mode to play a game early in the playtest process. Both Patriots and Royalists invaded the Federal Provinces east of the Parana River, and both sides gleefully activated Federal forces to attack the other side’s invading armies, or sneak back into their Provincial capital when the invaders moved off. I have never laughed so hard playing a traditional wargame in my life, and that includes all the shenanigans I’ve seen in many Here I Stand games.

Juan: That there will be published wargame that properly portrays the rich and complex historical scenario of the South American Wars of Independence in a comprehensive, non-biased, and accessible way.

Grant: What type of experience does the game create for players?

Keith: The Spanish and Argentine strategic military challenges are reflected for game purposes in Libertadores Del Sur in the constant cut and thrust of each side’s military and political fortunes. Spain’s strategic weakness, combined with the lack of Patriot political unity, creates very chaotic military game play, which I think Libertadores does a very good job of conveying. Just when one side gets up a head of military steam, it is quite likely that the rug will be pulled out from under your plans and assumptions. Certain actions in the game accurately trigger political-military events that change the dynamic of play. An example of this is the Argentine Patriot capture/liberation of Montevideo, which will cause the Banda Oriental (Uruguayans) local forces to rebel and become Federal opponents of the Argentines. This will also likely result in a Portuguese imperial invasion from Brazil, an outcome that pleases neither the Spanish Royalist nor the Patriot player. Modeling this political instability into the game, gives the military campaigns in Libertadores Del Sur an accurate depiction of the fluid circumstances and challenges under which both sides were forced to fight these wars.

Grant: What other designs are you currently working on?

Keith: The next project in the Libertadores trilogy will be the Campaigns of General Simon Bolivar’s liberation of Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador from 1810. The basic rules will be the same, but there will be some modifications to reflect the unique circumstances under which the wars for liberation were fought in Northern South America that were different from Liberatores del Sur. This mainly has to do with the multiple abortive republics that were proclaimed and Simon Bolivar’s almost superhuman ability to bounce back from adversity. I think the rules for guerilla warfare will have to be fleshed out to reflect the difference in the armies and fighting in this theater. There will also certainly be some fascinating leaders and event cards that will make the game as challenging and enjoyable as the first installment of the Libertadores Series. Some of these may include General José Tomás Boves and his Legions of Hell, Simon Bolivar’s War to the death, aquatic cavalry, slave revolts, race war, and the British Foreign Legion. Once we go to print publication of the first game, we will meet in Bogota to speak with Colombian Army military history experts to begin the second game. More to Follow.

Matt: Keith reviewed our plans for as many as two more follow-on games covering the rest of the Wars of Liberation in South America. I am also working with another friend who is a serious historian of the U.S. Civil War in eastern Kansas and Missouri; I live just outside of Kansas City. We think the COIN-lite system in the GMT Game The British Way is a good starting point. Also, we can tap into all the local knowledge of the interesting, unusual events for what is an obscure subject, and come up with a killer deck of event cards. It will be fun to work in Sterling Price’s two invasions of Missouri, which were significant, but with limited reach because of logistics.

Juan: I design a lot. That is basically what I do. I cook, clean, do the groceries, go to work, and design games. No sports, no videogames, no TV, no Netflix. I have a wife, 3 boys, a job and I design. So, I design a lot. I’m working on a matrix game on the French Revolution with an accompanying system-independent roleplaying campaign book. An introductory roleplaying module about the Beast of Gevaudan. A solitary tabletop game about the Atlantic Revolutions, that features similar themes as Liberatores, but in the adventure game genre and on a continental scale from 1763 to 1830. The prototype of which I’m programming in Inkle Writer for playtesting purposes and hopefully will be porting to Unity eventually. And finally, on the Third Edition of Imperios Milenarios, my most know creation. Still, I believe the development of Libertadores has been the longest project I’ve been

engaged in and is still totally deserving.

If you are interested in Libertadores del Sur: The Wars for South American Independence, 1809-1824, you can pre-order a copy for $50.00 from the Legion Wargames website at the following link: https://www.legionwargames.com/legion_LIB.html#

-Grant

Thank you Grant. A great honor for me to be featured in The Players Aid :o)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely Juan. Thank you so much for the time you and your design team put into the responses and the work on the game. It looks amazing and I cannot wait to play the game.

LikeLike