Legion Wargames is always working on interesting topics for games. They just seem to have so many good offerings and one that I recently saw announced on pre-order was a design by Andreas Pscheidl called Abyss of Lament: The Seven Years’ War, 1756-1763, which is somewhat of a tactical wargame with some twists. We reached out to Andreas and was more than happy to share with us.

Grant: First off Andreas please tell us a little about yourself. What are your hobbies? What’s your day job?

Andreas: Thank you for doing this interview. I am a great fan of your channel and site and I feel honored to be able to talk about my design with you. I’ve started wargaming in my early teens, some of my first – and still among my favorite – games being War at Sea, A House Divided and Wooden Ships & Iron Men. I then took quite a long break from wargaming, buying only about a couple of new games between 2000 and 2020. I mostly played RPG’s, miniatures and Eurogames in that period. It actually was the pandemic that got me back into wargaming. Besides gaming I enjoy reading and spending time outdoors (hiking, gardening, etc.).

Grant: What motivated you to break into game design? What have you enjoyed most about the experience thus far?

Andreas: Well, I have been designing games for myself almost as long as I have been playing. The first designs were – unsurprisingly – pretty bad, but over the years I came up with a few that actually are quite fun to play. I’ve never seriously considered trying to get them published before. With Abyss of Lament, maybe because of the time available due to the pandemic, I decided early on to make this at least “publishable“, that is, write a complete rulebook, not just some concept notes, do everything in English (not my first language), etc. I think the best part of the experience is seeing others engage with my ideas and having the chance to adapt and improve a design I’ve come up with myself. It’s really very rewarding.

Grant: What designers would you say have influenced your style?

Andreas: That’s a hard one to answer, because I get my influences and ideas from all over the place. Some of the inspiration has in fact come from miniatures rule-sets. For example, Arty Conliffe’s Crossfire is an eye-opener on non-traditional turn structures and the fact that a “Turn“ can be seen as a narrative unit more than a temporal one. Andrea Sfiligoi’s Song of Blades and Heroes is a good example on how to coax quite a complex range of results out of a pair of D6 throws.

Grant: How do you feel about publishing wargames? How is the experience?

Andreas: I am in the middle of experiencing it, so it might be too early to tell at this point. But the act of collaborating with professionals like Adrian van Helsberg and Nils Johansson certainly is something I have come to enjoy enormously.

Grant: What historical period does Abyss of Lament cover?

Andreas: Abyss of Lament allows you to play battles of the Seven Years’ War – more specific from its Austro-Prussian theatre, also known as the Third Silesian War – from the first European battle of the SYW (Lobositz, 1756) to the very last one (Freiberg, 1762).

Grant: What did you want the name of the game to convey to the players?

Andreas: I am very glad that you have asked me that. I have to take you on a short detour here. Frederick II., when he was not yet “the Great“ or even “II.“ but rather still crown-prince of Prussia, wrote a book called Anti-Machiavel. A handbook on how to be a good monarch if you will. In it he calls war an “Abgrund des Jammers“, to be avoided at all costs. I’ve seen this translated as “War is so full of misfortune“ in literature, but the literal translation would be: “War is an abyss of lament“. My reasoning for making this the game’s title was threefold: First of all, it sounds kind of dramatic. Secondly, it shows the complexity of Frederick’s character. His philosophical opposition against the usage of war as a means of policy didn’t stop him from launching the First Silesian War (a naked, and very successful land-grab if ever there was one) within months of the book’s publication. And finally I think it is a reminder that the Seven Years’ War actually was a terrible conflict for those involved. Terms like “lace wars“ or “cabinet wars“ give a quite misleading impression of 18th century warfare, at least in my opinion. It was not all show, maneuver and the occasional siege. Many battles of the SYW had more than 100.000 participants and casualty rates sometimes reached 30%, at Zorndorf even an incredible 40%.

Grant: What was your inspiration for this game? Why did you feel drawn to the subject? What was your design goal with the game?

Andreas: I am going to answer these three questions together. Sometime in the summer of 2020 – at the end of the long wargaming hiatus I already mentioned – I came across the old 1971 classic Napoleon at Waterloo and specifically a variant map and counter-set for this game that a very talented fan had uploaded on boardgamegeek. I played this a couple of times and came to realise that a) very simple wargames can still be challenging to play and lots of fun b) I really liked the Kriegsspiel-like look of the rectangular counters. About the same time, I came to read a lot about the Seven Years’ War, a conflict I had previously mostly only come across in the form of the French & Indian War. The European battles, especially those between Maria Theresa’s Austria and Frederick II.‘s Prussia therefore were quite fresh and intriguing to me. So it made sense to combine these two interests and make a game from them.

In doing so I had a few goals: I wanted to create a game that’s not too complex and has a reasonably short playing time. So the intent was not to create an exact simulation but rather a fun game that still shows off the relevant aspects of 18th century warfare, especially those aspects facing an army commander in battle. The tactical decisions of lower echelon commanders (e.g. what formations to adopt etc.) should be largely abstracted. I wanted it to present an attractive, uncluttered playing surface. That meant a reasonably small number of unit counters, little or no stacking, and limited status markers. Ideally the game should look like a period (either contemporary 18th century, or about a hundred years later) map or a kriegsspiel-like recreation from a military academy of this era. Hidden information should play a big role. Some elements of the final design directly stem from these consideration. For example leaders and artillery play an important part in the game, but are not represented by counters on the mapboard. Having hidden units means that the reverse side of the counters is already taken by showing the hidden status. My wish to implement some type of step reduction despite having only one „active“ side per counter led to the Wing Cohesion tracks for each wing.

With regards to gameplay, my maxim was to present the players with as many simple, yet meaningful (and often uncomfortable) choices as possible. The units you choose to activate, the way you position different units of a wing, the order in which you mount multiple attacks are – within not very complexly laid out limits – largely left to the player’s choice. The intended result is that when things go wrong, it’s often the player him- or herself who is to blame.

Grant: What type of research did you do to get the details correct? What one must read source would you recommend?

Andreas: In all things Seven Years’ War I think there is no way around the late Christopher Duffy. His books on the Prussian and Austrian armies were essential reading. For background information – besides some general histories on the Seven Years’ War – I really enjoyed Tim Blanning’s biography Frederick the Great: King of Prussia. It goes very far in showing the complexities of Frederick’s character. I’ve also read some excellent German books. The most impressive one of these was Eberhard Kessel’s book on the final years of the Seven Years’ War.

And finally there are two outstanding online sources available. The Project Seven Years’ War (http://www.kronoskaf.com/syw/index.php?title=Main_Page) is an enormous collection of articles on battles, units, personalities etc of this conflict. It has been a great help in my research. The second source and the one I would heartily recommend to anyone interested in dipping their toes in, is Jeff Berry’s Obscure Battles (http://obscurebattles.blogspot.com/). His descriptions of battles from 334 BC to 1898 are very well researched, highly entertaining and often at least slightly iconoclastic. But the most impressive part probably are the maps, which not only show a very realistic approximation of the historical terrain but also the meticulously researched footprint of historical formations on this terrain. The articles on the battles of Lobositz, Kolin and Leuthen were a huge inspiration for me and I recommend them highly.

Grant: What battles are highlighted in the game?

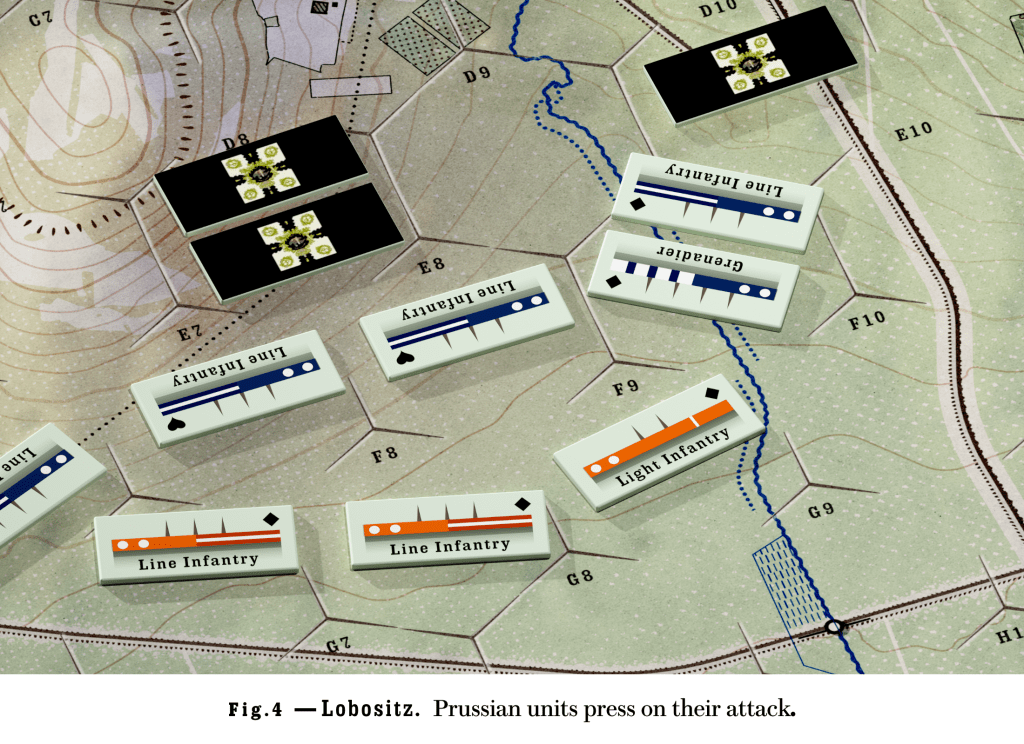

Andreas: AoL allows you to play the battles of Lobositz (1756), Kolin, Leuthen (both 1757), Hochkirch (1758), Torgau (1760) and Freiberg (1762). Before I started reading about the Seven Years’ War I always had the impression that most Age of Reason battles were pretty samey. But actually the opposite is true. These are very different experiences. With the exception of Hochkirch they all have in common that the Prussians are the attackers. Lobositz is a small battle where the Austrians actually are more interested in preserving part of their force to relieve an allied Saxon garrison. The terrain of hills and rivers funnels the action pretty much into the center of the map. Kolin is a much bigger, more sweeping battle with the Prussians attacking an Austrian army well established on a plateau. Leuthen gives the Prussian the option (which they are not forced to take) of setting up most of their forces on the Austrian flank, perpendicular to the Austrian line. At Hochkirch, the shoe is on the other foot with uncharacteristically aggressive Austrians catching an incautious Prussian army in a pincer movement. At Torgau, the Austrians are holding a strong and partially fortified ridge but are attacked from the front and rear at the same time. Freiberg is the final battle of the Seven Years’ War, does not feature Frederick and shows a Prussian attack into difficult terrain against a mixed Austrian/Imperial army.

Grant: What elements from the Age of Reason and battles from the Seven Years’ War did you need to model in the game?

Andreas: I think the largest challenge by far in modeling Frederick’s battles comes from historical situation faced by the Prussians. In almost all battles they were on the attack, against opponents who often significantly outnumbered them. To make things worse, the Austrians often enjoyed very good defensive terrain. While Prussian troop quality was excellent, the Austrians had significantly closed the gap in infantry quality since the First and Second Silesian Wars (part of the War of the Austrian Succession) in the 1740ies, while Austrian cavalry had always been excellent. So what gave the Prussians a chance at victory? I think their main advantage lay in the truly outstanding „middle management“ of the Prussian army, the company, battalion, brigade commanders who gave Frederick unmatched control over his forces. While maybe not comparable to Napoleon or Marlborough, Frederick himself was an outstanding, audacious commander, while his opponents were usually either rather poor leaders (Charles of Lorraine) or very cautious (Graf Daun). In game terms this is represented by the units of both sides of a given type having generally the same values, but the Prussians generally enjoying advantages in having a greater hand-size, more AP per card, more Heroic Commanders and a higher starting level of Wing Cohesion.

Grant: How does the game use cards?

Andreas: AoL uses cards as the heart of its engine, but its not a CDG in the classical sense. There is no hand building for example. In practice it actually has some elements of a chit-pull system. Depending on the quality of your army commander you draw between 2 (Charles of Lorraine) to 4 (Frederick II.) cards. Each player has his or her own deck of cards. Alternating by round you play one of your cards. You get to redraw only when your hand is completely empty. This forces the player to deal with the options given by fate, but better commanders (with larger hand-sizes) usually have more options, the ability to plan further ahead and even regulate to some degree the length of a turn. Each new turn all cards are reshuffled and provide the new drawing deck.

Grant: Can we get a look at a few sample cards and you explain how they work?

Andreas: Sure. I can even do one better and explain all the cards, because there actually are not that many different types: Wing cards and Commander-in-Chief cards are mainly used to move units (and may also be used for rally and reform). Players usually have two wing cards per wing and two C-in-C card per army. They provide from 2 to 5 Activation Points, with 1 or 2 AP activating one unit. Artillery Support cards are placed in a support area for later use, giving a hefty bonus to one individual combat. Sometimes their mere existence will give the opponent pause before committing to an attack. Each side of a scenario has one Asset card that provides some scenario specific advantage. This might be Frederick II, risking his life to rally troops at Kolin or the Austrians bringing in reinforcements from their right wing at Leuthen for example. And finally both players have a single Time card. If both Time cards have been played, a turn immediately ends. This makes for a random turn length but with a high probability that at least two thirds of all cards will be played per turn.

Grant: How are reconnaissance assets like light cavalry and Vedette dummy-units used? What advantages do they provide?

Andreas: All units start hidden in AoL. This confers the obvious advantage that the opponent doesn’t exactly know the type of the unit. Set-up areas are usually somewhat ambiguous (or very ambiguous, like for the Prussians at Leuthen) so the opponent doesn’t even know at first to which wing a unit belongs. Vedettes can be set-up everywhere, so one of their uses is deceiving the opponent about the actual set-up. The second advantage of being hidden is that hidden units can be activated with any Wing or C-in-C card, not only those of their suit. This represents the unit being still uncommitted, with a corresponding greater ease of manoeuvrer. This is relevant for the second use for Vedettes: Revealing enemy hidden units (and screening friendly units from enemy Vedettes). The downside is that Vedettes are removed when revealed themselves, so they are a limited resource. Hussars – light cavalry – are just as fast as Vedettes and are not removed when revealed. They can actually fight, although not very well. The upside is that they are very hard to kill. They might be disordered and run away, but they usually survive unless cornered or very unlucky.

Grant: What is the anatomy of the counters?

Andreas: A unit counter holds basically three main points of information. The suit of cards shows to which wing of the army the unit is assigned to. The number of “Buttons“ represents the unit’s Movement Points (from 2 to 4) and the number of “Arrowheads“ the Combat Strength (from 1 to 4). Note that units are semi-generic. That means an Austrian Line Infantry counter of the Hearts wing may represent formations of Krottendorf’s brigade at Lobositz and of the Puebla’s brigade in the Leuthen scenario for example. This system allows the use of large, attractive counters without the need of a huge amount of counter-sheets.

Grant: What is the scale of the game and force structure of units?

Andreas: AoL is a grand-tactical game. One hex is around 600 metres across, a turn represents about an hour to an hour-and-a-half. A single unit counter equals approximately a brigade-strength formation of infantry or cavalry. All armies are divided into three or four wings (of from two to six units each). The number of unit counters per scenario is quite low. At Lobositz 9 Prussian units fight 11 Austrian ones. At Torgau it is 18 to 21.

Grant: How does combat work in the design? What are the different ways in which hits can be absorbed?

Andreas: I’ll answer these two questions together again, if I may. Combat is always between individual units and happens in sequence. That means that the outcome of each combat may influence those that follow. Each unit has a Combat Strength (CS) from 1 to 4. Players each add up their CS and – if applicable – one or more situational modifiers. The list of these is quite short (around ten) and ranges from having artillery support, terrain advantages or benefiting from flanks secured by other units. The total modifiers are then compared, with the player with the higher value gaining the differential as a Combat Bonus. Both players then roll a die each, one of them adding the Combat Bonus. Depending on the differential between these results the defeated unit suffers from 0 to 5 hits. If a unit suffers more hits than it can absorb, it is eliminated. Note that units being eliminated is a big deal in AoL. You do not have that many of them to begin with and each elimination gains the opponent 1 VP. Fortunately units are – at least at first – quite resilient.

Grant: Why did you decide not to use a Combat Results Table? What advantage does your system provide?

Andreas: The main advantage I see is that this system gives the loser of each combat a free and often uncomfortable choice on what kind of hurt to accept. In some cases this choice is obvious – a fresh attacker taking 1 Hit will almost always reduce Wing Cohesion for example – but more often than not, especially when taking 2 Hits, the choices will become hard. Do I need to hold that hex or can I fall back? Is it better (or at least less bad) to be disordered and more vulnerable to a follow-up attack? Or should I reduce Wing Cohesion and give the opponent 1 VP? These decisions are often agonizing, may prove to be wrong in the long run, and actually make for a very fun game with high player involvement.

Grant: What do the maps for each battle look like?

Andreas: As I’ve alluded to before, the look I envisioned were the military maps of the 19th century. Maps one could imagine cadets of Sandhurst or Saint-Cyr were studying when learning about that then not so distant European conflict, the Seven Years’ War. Personally I think this goal has been achieved – thanks to the outstanding work of the game’s artist, but please judge for yourself:

Grant: Who is the artist for the game? How has their work assisted you in creating a thematic and true to history game?

Andreas: Nils Johansson is the artist for AoL. I find his work truly astounding, be it the cover, the maps or the counters. It’s interesting that he and I both came up with the idea of a faux 19th century Kriegsspiel look by ourselves. My early drafts were much, much less pretty than Nils’s but they were a lot closer to the final style of art than the prototype I submitted with Legion Wargames, which was in a quite traditional square-counters style.

Besides his great artistic talent, Nils is also responsible for the great topographical accuracy of the maps. The location of rivers, towns, hills etc. has been researched meticulously both from the historical maps (which often are quite unreliable) and modern digital topographical data.

Grant: What type of an experience does the game create?

Andreas: My goal is to give the players the best possible impression of an army commanders experience in 18th century warfare for the least rules overhead. The players start out with a well ordered, resilient army, but little knowledge about the dispositions of the enemy. As time goes by, the knowledge about the enemy increases, while the capabilities of the army decrease because of the loss of flexibility in activating revealed units, disorder, wing cohesion loss and being locked into ZOC’s. The combat system, not least the regular losses due to attrition, and the relative costs of rallying and activating lead to a steady downward spiral in army capability. The player who manages this dynamic better should usually come out victorious.

Grant: What are you most pleased about with the design?

Andreas: I think I am most pleased that I still find playing the game very enjoyable despite the many hours I’ve already spent doing so. To be honest, that was my ultimate motivation for the design: Making a game on the subject that I really wanted to play. I feel honored that other players, some of them with a much longer and broader wargaming experience than myself, have also enjoyed playing it.

Grant: What has been the response of playtesters?

Andreas: The response has been very positive, actually from the start, even though the game certainly still needed much improvement back then. It was the initial playtesters who convinced me that publication would be a serious option for this game. Having said that, my playtesters and especially the developer, Adrian van Helsberg, have been a huge help in improving the design from where it started out. More recently, Adrian and Nils visited this year’s Bellota Con in Spain, and presented two of AoL‘s scenarios to various interested players. Adrian reports that he managed to explain the core rules in approximately ten minutes, after which participants were able to play competently and without having to interrupt the game to ask questions. The rules made sense for them and were implemented easily. The game flowed smoothly. Players well versed in the Seven Years’ War felt the rules captured satisfactorily the dynamics of linear warfare. Even those who weren’t that familiar with the period had no difficulty integrating the system. I find that very encouraging and only regret having not been there myself.

Grant: What other designs are you working on?

Andreas: My only other current project – very much on the back-burner now because of AoL – is a series of games tentatively called the Petite Guerre System (PGS). These are to be strategic CDG’s about smaller, shorter conflicts in the 16th and 17th centuries. They should all be playable on a 11 x 17“ map, have less than 50 counters and less than 20 cards each. One game is already mostly finished and has actually been lots of fun in playtesting. It is about an immensely obscure war in Central Europe, that has the advantage of being almost perfect to model, as it lasted only two years, had very balanced but somewhat asymmetrical opposing forces and included battles, sieges, raids and political maneuver. The next step will be adapting the system to a better known conflict, the Williamite War in Ireland, 1689-1691.

Thank you so much for your time in answering our questions Andreas to help us all better understand the intricacies of the design. I am very excited to give this one a go and love the look and feel of the components.

If you are interested in Abyss of Lament: The Seven Years’ War, 1756-1763, you can pre-order a copy for $65.00 from the Legion Wargames website at the following link: https://www.legionwargames.com/legion_AOL.html

-Grant