In mid 2019, I discovered the amazing solitaire game The Wars of Marcus Aurelius from Hollandspiele, which was my first introduction to the genius of Robert DeLeskie. The game is a solo only game that deals with the Roman defense of the Danube against several different Barbarian Raiders. The great thing about the game is that it uses cards, that not only provide the fuel to fire your actions, but also provide lots of detailed history about the time. I loved it and have played it north of 15 times now! Robert then designed a follow up to that game called Stilicho: Last of the Romans that was also amazing. So with my past experience with his games, when I heard about Fire & Stone: Siege of Vienna 1683 from Capstone Games I had to get more information on the game and reached out to Robert to see if he would answer some questions on the design.

Grant: What historical event does your upcoming game Fire & Stone: Siege of Vienna 1683 cover?

Robert: The game covers the Ottoman siege and Habsburg defence of Vienna during the summer of 1683. It focuses on the tactical conflict that occurred outside the walls, between the Löbl and Burg bastions. That is to say: it doesn’t emphasize other aspects of the siege or broader conflict, such as political machinations, broader logistical concerns, or the climactic field battle between the Holy Roman Empire, Polish cavalry, and the Ottoman army.

Grant: What was your inspiration for this game?

Robert: In 2018, I read Andrew Wheatcroft’s The Enemy at the Gate a book about the siege and the historical context surrounding it. I was rivetted by his dramatic descriptions of 17th century sieges, which seemed to have more in common with World War I trench warfare than the stereotypical image of ancient or medieval sieges with their ladders, catapults and siege towers. The event itself is one of the most famous sieges in history, of course, as much for the dramatic, last minute arrival of the relief force as for the siege itself. But the book’s focus on the tactics of early-modern siegecraft stuck with me, and sent me down a bit of a rabbit hole. I was already interested in the long-running conflict between the Ottoman Empire and their European neighbours as a possible subject for game design, and this seemed to be a good, bite-sized way into the topic.

Grant: What does the “Fire & Stone” part of the game title say or mean about the history?

Robert: The title comes from Christopher Duffy’s book, Fire & Stone: The Science of Fortress Warfare 1660-1860. Duffy is one of the great historians on the topic of siegecraft, and I always had several of his books close at hand while designing the game. The title speaks to the contest between attack (fire) and defence (stone), and I felt it captured the intense drama I was hoping to evoke with the game.

Grant: What from the history did you want to make sure to include in the design?

Robert: I wanted to create a fun and accessible model that illustrated the tactics of 17th-century siege warfare. I also wanted to outline the decision spaces open to the Ottoman and Habsburg leaders (Kara Mustafa Pasha and Count Ernst Rüdiger von Starhemberg, respectively); meaning, I wanted the game to generate the kind of pressures the commanders may have felt, while offering players the same sorts of options each leader had to respond to circumstances.

The siege was filled with memorable incidents, and I tried to acknowledge as many of these as I could as events on the strategy cards. Finally, I wanted the game to produce some of the intense drama depicted in Wheatcroft’s book, as well as eyewitness accounts of the actual siege.

Grant: What sources did you consult to get the background correct? What one source would you recommend as a must read?

Robert: The Enemy at the Gate by Andrew Wheatcroft is an excellent, English-language introduction to the subject and the one I’d recommend as a starting point. There are also John Stoye’s The Siege of Vienna: The Last Great Trial Between Cross & Crescent, and Thomas Barker’s Double Eagle and Crescent: Vienna’s Second Turkish Siege and It’s Historical Setting.

English translations of Turkish histories of the siege are rare indeed, but Halil İnalcık’s The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age, 1300-1600 provides some valuable background from a Turkish perspective, as does Mesut Uyar and Edward J Erickson’s A Military History of the Ottomans. On the general topic of gunpowder siegecraft, Christopher Duffy’s Fire & Stone is foundational, as are his Siege Warfare: The Fortress in the Early Modern World 1494-1660, and The Fortress in the Age of Vauban and Frederick the Great, 1660-1789. I also consulted a number of articles on different aspects of the siege, Habsburg and Ottoman diplomatic relations and military history, and 17th century warfare.

Grant: What is the object of the game?

Robert: The object of the game depends on which side you play. The Ottomans must capture the city, and the Habsburgs must defend it.

Grant: What about a prolonged siege did you feel was important to include in the game?

Robert: At 57 days, Vienna wasn’t a particularly long siege by historical standards. The grim deprivations caused by starvation and disease didn’t play as significant a role as they did in other situations. Still, morale was an important factor, and during the course of the game, both sides will likely see their forces’ will-to-fight ground down. A total loss of morale is one of the ways either side can lose the game, and it’s an important resource to manage when playing.

Grant: What different types of cards are used in the game?

Robert: There are three types of cards. Strategy Cards allow players to take basic actions or trigger special events which temporarily break or modify the rules in interesting ways. Tactic Cards provide boons or bonuses during battles. Troop Cards represent the forces available to either side during an assault or sortie. I should mention that “strategy” and “tactic” are a bit of a misnomer as I’ve used them here. I started with those names as a way of distinguishing between two scales of action. But by design, the game is more tactical than strategic. At the eleventh hour, I wanted to rename them to “action” cards and “battle” cards, but that risked introducing its own confusion, so we decided to leave them be.

Grant: The Strategy Cards are the engine of the game. Why do you feel this card driven mechanic was perfect for your vision?

Robert: This is my third card-driven game – I guess there is something I like about the mechanic! To me, the cards represent a useful way of abstracting the resources available to players at a given moment of decision. Stripped of events, cards are the simplest form of action-economy; they collapse the essential logistical components of warfare, things like money, supplies, ammunition, and so on, into an abstract, easily understood form.

Events represent the opportunities that unexpectedly emerge during the course of the conflict; intelligence, a suggestion by a junior officer, individual initiative, or just plain luck. The best ideas don’t always come up at the right time, and the random nature of when the events are drawn is a great way of modelling that. Of course, events are also a way of injecting flavour and history into the game.

One thing I really like about CDG’s is what is sometimes called “card angst.” That’s the tension a player feels when deciding whether to use a card for a simple action, or for a more interesting event. An event may be powerful, tempting a player away from their plan, but the timing may be wrong. Do you risk it? Or everything may line up perfectly, which is a great feeling! I think this is an excellent way to help create drama, and also reproduce some of the psychological conditions of making difficult decisions under pressure.

It’s this mix of simple, abstracted economy and emergent opportunity that I think works well for depicting certain kinds of conflicts, and I felt it was a good fit for Vienna.

Grant: How has your past experience with other CDG games helped you with Fire & Stone?

Robert: Balance is a really tough thing to get right with CDG’s. Atop a base layer of actions, you need a mix of general and specific events, along with responses to enemy card play, and ideally these can chain together into interesting combos. You also need to mix the power level of different events, acknowledging how that can change drastically depending on the players’ situation (a card that is useless in one set of circumstances could be vital in another). Balancing all of these potentialities in a purely mathematical or scientific way is beyond me! While I will sometimes map or flow-chart things out, I tend to work more from intuition and feeling, which requires repeated playtesting. Hopefully, achieving a fun, fair, and reasonably balanced mix of events is something I’ve gotten better at through experience.

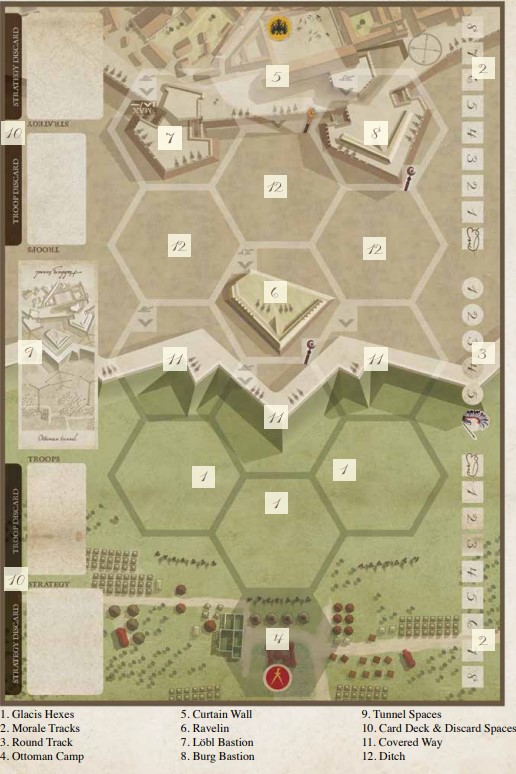

Grant: Let’s talk about the board. It appears to have hexes. Why was this your chosen format for the game?

Robert: The limited number of spaces is really important to game, and was a design goal from the very start. The reason is that, in terms of tactics, sieges typically concentrated on a predetermined weak spot in the defender’s fortifications. This vulnerability would be selected by engineers, and often both sides were well aware of it. This was certainly the case at Vienna. So right off the bat, there was no need to depict the entire city, particularly when 90% of it would never have come into play at the tactical level of the game.

Another reason for the limited number of spaces is the nature of gunpowder fortifications themselves. They were designed to channel attackers into a slugfest through an established pattern of defence-in-depth, forcing the besieger to spend valuable time and resources capturing a series of keystone locations on their way to the city walls. By the 17th century, it was clear that in most situations, given enough soldiers and materiel, practically any city could be taken. The determining factor was time. Were the defences sufficient to delay the attackers until a relief force could be assembled, or the besiegers food ran out, or the winter came, or the political situation changed?

On the tactical level, sieges are battles of attrition run against the clock, and when you think of them this way, you can see that you don’t necessarily need a lot of map spaces to depict this.

In terms of development, the game was originally even simpler: a series of cards laid out in a T-shape, with each card representing a milestone on the way from the glacis (outer field) to the curtain (inner) wall. I wanted players to focus on the tactics required to capture or defend each of these spaces. In play, a single path proved a little too limiting for players, so I expanded the game from one lane to three. Spatially, this introduced the concept of adjacency, which became important to how the Ottomans can leverage their superior numbers in the game. It also reflected the history: the Ottomans ran three main lines from their camp up to the walls.

I experimented with different shapes for each of the zones by drawing and then cutting shapes out of foam core. Hexes were the simplest and most versatile. There’s a reason they’re such a mainstay in wargames!

Grant: How do players build fortifications in the hexes? What are the differences between Structural and Improvised Fortifications?

Robert: The Habsburg player starts with a set number of Structural fortifications, representing the permanent defences of Vienna, constructed out of brick, stone or earthworks. These can’t be added to or repaired during the course of the game (they took months or years to construct, and were enormously expensive).

Improvised fortifications represent the non-permanent defences of the city. Immediately prior to the siege, the great siege architect Georg Rimpler added several layers of hastily constructed barriers to the existing structural fortifications. These included a wooden palisade wall on top of the covered way (i.e., on the top of outer-facing side of the ditch), as well as wooden blockhouses and ditches inside the dry moat that surrounded the west side of Vienna.

On the Ottoman side, improvised defences represent the trenches and siege lines running from the camp up to the covered way, and then snaking through the ditch. Once the Ottomans captured key locations such as the covered way or ravelin, they added their own barriers (typically wicker baskets filled with earth) to defend their troops.

Improvised defences can be added throughout the course of the game by either side, at a cost of time (a turn) and resources (a card or special event).

Grant: What are the functions of the different locations on the board such as the Curtain Wall, Ravelin and the Burg Bastion?

Robert: The locations on the map represent the actual fortifications at Vienna. Each location is designed to reflect its role in bastion fort design. For example, the glacis (the wide, empty field in front of the ditch) is easily taken by the Ottomans through entrenchment, but they are exposed to the full force of Habsburg firepower and may suffer casualties while doing so. The ravelin is heavily fortified, but its capture greatly weakens the defender’s ability to bring fire to bear on attacking troops. This is represented by the large number of cannons on the ravelin (four of the Habsburgs nine guns). The Habsburgs didn’t actually have that much artillery on the Burg ravelin, but in the game this represents how important the outer works were in providing overlapping and covering fire for defending troops.

I also tried to incorporate some of the specificities of the historic fortifications. For example, the Löbl bastion was awkwardly designed, so in the game it can hold a maximum of one fortification instead of the usual two.

Grant: What different actions are available to players? How are each sides actions different?

Robert: The Ottomans can Entrench (move onto the glacis and add improvised fortifications, representing their trenches), Assault (attack a Habsburg controlled position), Mine (attempt to tunnel under the defences and explode them from beneath), Fortify (add improvised fortifications to a location they control) or Bombard (concentrate fire on fortifications).

The Habsburgs can Sortie (attack an Ottoman controlled location), Mine, Fortify or Bombard (target Ottoman troops).

Some of the actions that outwardly appear similar play out somewhat differently. For example, the Habsburgs automatically gain morale when they Sortie, regardless of whether they win or lose the battle, while Ottoman morale decreases in the face of a loss.

Grant: Let’s talk about the Mine Action. How does this work? What did this represent from the history?

Robert: Undermining was an important part of medieval and ancient sieges, but it assumed new prominence after the proliferation of effective gunpowder weapons and bastion fortress design starting in the late-fifteenth century. Brick and earthwork defences were highly resistant to artillery fire, especially compared with the high stone walls of castles (dirt is excellent at absorbing the impact of cannon balls, and a low brick wall is less likely to suffer a total collapse than a top-heavy stone wall). Attackers learned that a good way to circumvent these fortifications was to blow them up from underneath. The resulting earthen debris could provide a ramp down into a ditch, or up the side of a steep outer work or wall. Digging mine shafts under enemy fortifications and packing them with explosives thus became an important tool of siege warfare. Defenders understood this, of course, and responded by digging their own mines, hoping to intercept the attackers and collapse their tunnels before they reached the defences.

In the game, a player draws a random tunnel tile from a bag, checks it, then places it face down into the mining space on the game board. Each tile has a value (1, 2 or 3 for the Ottomans; 1 or 2 for the Habsburgs). When the value of the tiles totals 4 or more, the player can cause an explosion, removing 1 structural fortification or 2 improvised fortifications. The disparity in tile values represents Ottoman superiority in this style of warfare.

Events can alter the effects of explosions, requiring fewer tiles, magnifying the destructive capability (such as removing all fortifications from a location, or causing two simultaneous explosions), or collapsing an enemy’s tunnel (forcing them to remove some or all of their tiles).

Grant: How does a Battle work in the design?

Robert: Battles (Ottoman assaults or Habsburg sorties) are played using Troop Cards secretly chosen by the player, along with the optional use of a Tactic Card. Ottomans can usually play more cards than the Habsburgs in both attack and defence, but the Habsburgs typically have stronger defences and start with more guns. Troops have numeric value of 1 (poor quality), 2 (average quality), or 3 (elite). Players reveal their cards at the same time. The defender’s fortifications neutralize a certain number of attacking troops, which means their value doesn’t count in the final tally. Artillery dice are then rolled to determine the number of troops eliminated in the battle (removed from the game). Each side then adds the value of their remaining front-line troops, and the higher number wins, either holding the space, or capturing it. An attacker who loses can potentially sacrifice some troops to remove improvised fortifications, or possibly cannons.

Tactic Cards potentially modify the different steps of this battle procedure.

Grant: Why did you decide to only allow the play of 3 Troop Cards in any one Battle?

Robert: I wanted to keep the math as simple and streamlined as possible. This was for the players’ sanity as well as my own! I experimented with lots of different combinations during design and testing. Three seemed to be the right number. Of course, the Ottomans can play more than three cards depending on how much space they control and whether or not they are in supply. This represents the superiority of their numbers, and their ability to muster large scale assaults.

Grant: How do players use the Recover Action during a Battle?

Robert: Recover allows players to replay Troop Cards that have already been spent, at a cost to their side’s morale. Your troops are weary and wounded. Calling them back to the front is sure to induce some misgivings, but may be necessary.

Grant: What are the different side’s Victory Conditions?

Robert: Each side can win in several ways. For the Habsburgs, the simplest way is to survive five turns, to the end of the game. At this point, the relief army shows up and drives the Ottomans from the field (the historical outcome). Because of the limited scope of the game, which is played from the perspective of the two siege commanders (Kara Mustafa and Starhemberg), I felt it was fair to consider the arrival and victory of the Austro-German-Polish forces a “fixed point.” No matter what kind of historical game you’re designing, there are always assumptions rooted in the actual history that you take as your starting or end points, and I decided that this fit the kind of game I wanted to make. If players prefer something more open ended, they can always play their favourite game about the Battle of Kahlenberg after turn five!

Besides surviving to the end of turn five, the Habsburgs can win by breaking Ottomans’ morale, or causing enough casualties to make it impossible for them to sustain the siege. These are unlikely though possible outcomes, which I feel reflects the historical situation.

The Ottomans win by capturing either one key location (the curtain wall), or two secondary locations (the ravelin and the Burg bastion). Both of these represent a fatal breach of the Viennese defences. Historically, a breach was a definite possibility; had the relief army been delayed a few days longer, observers and historians agree it likely would have occurred. Whether the Ottomans could have pacified the city through the street fighting that would have followed, while simultaneously holding off Sobieski and Lorraine, is a question open to debate. But a breach certainly would have changed the equation on September 12 when the Battle of Kahlenberg took place.

The Ottomans can also win by eliminating all the Habsburg troops, or reducing Habsburg morale to zero. Historically, these were unlikely outcomes, at least as long as the arrival of the relief army seemed inevitable. Part of this is down to leadership. While the city’s population feared surrendering to the Ottomans and had a great desire to defend the capital, Starhemberg also employed the right combination of tactical savvy and discipline to essentially take capitulation off the table. The Habsburg player will have to arrive at this balance themselves by determining when and where to risk sorties, which boost morale but potentially reduce their troop pool.

Grant: What are some basic strategies that each side should keep in mind?

Robert: I’d rather let players discover the strategies for themselves! One thing I will say is that neither side should neglect mining. Also, while the first few turns may seem very difficult for the Ottomans, the dynamic can quickly change if and when they take the ravelin, reach the ditch, or reduce the Habsburgs defensive firepower.

Grant: What are you most pleased with about the design?

Robert: I worked a long time on the battle system, trying to incorporate things like fog-of-war, the effects of fortifications and artillery, the inequality of the force-sizes, and the significance of casualties while keeping it as simple, fast and fun as possible. I also wanted to illustrate the human cost of siege warfare, which essentially trades lives for ground held or gained. I’m not sure if I succeeded, but I still find the battles engaging, which I count as a victory after a seemingly endless number of games during design and playtesting!

Grant: When can we expect to see Fire & Stone released?

Robert: The game is currently available for pre-order on Capstone Games’ website (https://capstone-games.com/board-games/fire-stone-siege-of-vienna-1683/), and should start landing on the shelves of your FLGS sometime in October.

Grant: What other designs are you mulling over?

Robert: Clay Ross (publisher, Capstone Games), Donal Hegarty (graphic designer) and I are discussing possible sequels to Fire & Stone. The 16th, 17th and 18th centuries are filled with fascinating, gameable sieges. I’m also interested in looking at other eras, including ancient and medieval sieges. Of course, all this will depend on how Fire & Stone is received.

For some time now, I’ve been interested in designing a game about the broader Ottoman-Habsburg-Venetian conflict, particularly the contest for the Mediterranean. I hope to get back to work on that sooner rather than later!

I’m also working on a medieval monster-hunting game, but that’s not strictly a wargame so I’m not sure it’s of interest to your readers ;).

Thank you Grant and Alexander for inviting me to participate in this Q&A! I hope it was helpful for those interested in learning more about Fire & Stone: Siege of Vienna 1683.

Thank you for your time in answering our multitudinous questions Robert. We appreciate your designs and really wanted to get more information to share on Fire & Stone and you have definitively given us that.

We recently were able to play an advance prototype copy of Fire & Stone and you can watch our review video at the following link:

If you are interested in Fire & Stone: Siege of Vienna 1683, you can pre-order a copy for $49.95 from the Capstone Games website at the following link: https://capstone-games.com/board-games/fire-stone-siege-of-vienna-1683/

-Grant

Grant,

Thanks for publishing this interview. It was an interesting read with insight into both the designer’s passion for the subject and the thoughtful process of bringing history to the tabletop. I purchased “Stilicho: Last of the Romans” in part based on your recommendation, and have been thoroughly enjoying it. (Congratulations, Mr. Deleskie, on a terrific game, by the way.) Unfortunately, I don’t have the gaming partners to play “Fire and Stone,” but I may have to find a few in order to justify picking this one up!

LikeLiked by 1 person