Stephen Rangazas has been active kind of behind the scenes over the past few years with his development work on Fall of Saigon: A Fire in the Lake Expansion. He has used his background and research capabilities to great effect as he did the background work on the Event cards in the game. From that experience, he has now come forward with his own design in The British Way: Counterinsurgency at the End of Empire from GMT Games which was announced last year. We reached out to him for one of our designer interviews and he was more than willing to share with us some of the inner workings of the design.

*Please keep in mind that the materials used in this interview including components, board and cards are not yet finalized and are only for playtest purposes at this point. Also, as the game is still in development, details about the game may still change prior to publication.

Grant: First off Stephen thanks for taking the time to answer our questions. Please tell us a little about yourself. What are your hobbies? What’s your day job?

Stephen: I’m a PhD candidate at George Washington University studying political science with my research focusing on civil wars. My research, teaching, and game design take up most of my time, but I try to squeeze in the occasional hike, often on trips to western North Carolina, or organize game nights with fellow graduate students to play more mainstream boardgames not on depressing conflicts.

I should also mention I grew up in Indiana and attended Indiana University for undergrad so I’m from your neck of the woods. [Editor’s Note: We can all rest assured that Stephen has received a top notch education from the best university in the world and his research will be both thorough and accurate and his conclusions sublime! I know from experience as I graduated in 1997 with my BS in Public Affairs Management from the School of Public and Environmental Affairs at IU Bloomington.]

Grant: What motivated you to break into game design? What have you enjoyed most about the experience thus far?

Stephen: I started game designing in late 2019 while researching a case for one of my working papers and thought I wish a COIN game covered this period. I started working on an expansion for a pre-existing COIN game and then pitched it to GMT a few months later. That game has been announced and is another expansion for Fire in the Lake called Sovereign of Discord. For the last two years, I got to experience nearly all aspects of the design process as a playtester, developer, and designer working with people like Joe Dewhurst and Jason Carr at GMT. It was useful to experience many different sides of game design when I was just starting to develop my own principles of design and development.

Grant: What designers have influenced your style?

Stephen: I’ve been wargaming since early 2014 so I’ve been fortunate to at least try many of the most famous designs in the hobby. I think Volko and Brian Train probably had the greatest influence on my designs. Given I’m designing in the COIN Series that’s probably not too surprising, but I’ve also found Volko’s approach to designing to align with a lot of what I’ve been taught as part of modelling and research method in political science academic research. Brian has probably impacted every designer of games on insurgency. It’s a testament to how many insurgency games Brian has designed that between The British Way and two other 4-packs I’m working on, he has designed at least one previous game on a topic in each of the packs (e.g. EOKA on Cyprus).

I should also mention that when I play wargames, I always read a book with the game to learn more. I’ve found that one of the most useful methods of learning game design has been reverse designing major games by reading the histories recommended by the designer and trying to figure out why they made the design choices they did. I’ve done this for all the COIN Series games and have found it useful for distilling lessons for my own designs.

Grant: What do you find most challenging about the design process? What do you feel you do really well?

Stephen: The most challenging part of design for me is definitely the rules clarity and editing that occurs fairly late in the process. You want the rules to be clear but also concise. However, players come with different level backgrounds in terms of experience in wargaming or even gaming generally. This was a major issue with The British Way because in our playtester pool we had a combination of veteran COIN players and others seeking to use The British Way as their intro to the series. There were a lot of concepts that we and the veteran testers were probably taking a bit for granted that we’ve spelled out a little more thanks to suggestions from those new to the series.

The easiest part of the game design process for me is actually the research and initial working out of the model. Many of the topics for The British Way I had already researched for work and when abstracting from the history of a specific topic I also have the advantage of being able to draw on theories of civil war dynamics from my academic area.

Grant: What got you interested in designing a COIN Series game?

Stephen: My research area has probably played a major role in getting me interested in the COIN Series. I think the series does a great job of presenting a strategic overview of these types of conflicts and wished that some topics were covered in the series so that pushed me to design them.

Grant: What historical events does The British Way cover?

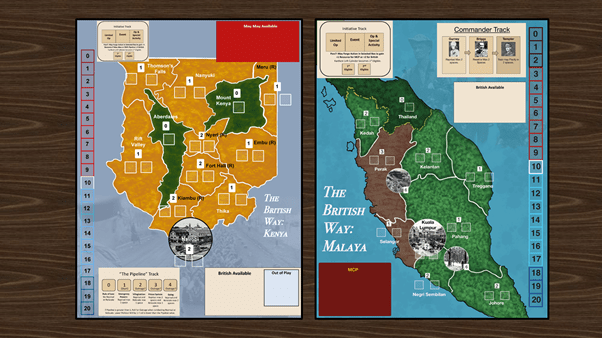

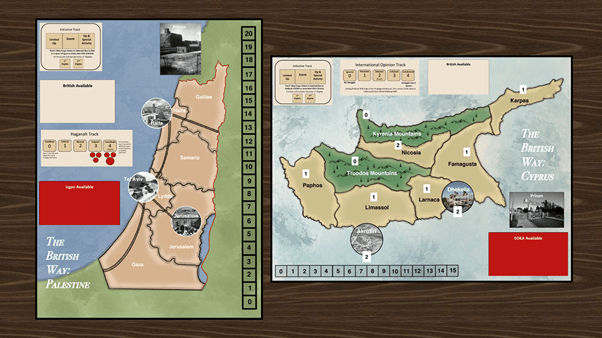

Stephen: The British Way covers four British counterinsurgency campaigns during the process of decolonization immediately after World War II. These include campaigns against larger insurgencies that sought to contest territory and topple colonial rule through armed conflict such as in Kenya and Malaya, but also smaller more clandestine armed groups that sought to wear down British prestige to force a withdrawal as in Cyprus and Palestine.

Grant: What does the subtitle Counterinsurgency at the End of Empire mean to you? What should players know going into the game?

Stephen: I wanted to make it clear to players that this was a game exploring counterinsurgency that occurred during decolonization but not necessarily a game about the broader process of decolonization. I would love to see a game on the larger process, but The British Way is primarily about the four specific campaigns, and also illustrates how these campaigns influenced the development of Western counterinsurgency doctrine. By including the campaign scenario that links the games together, we are able to provide more insight into decolonization.

Grant: What is your thesis for this game and what themes does it deal with?

Stephen: The main thesis of the multipack is exploring the notion of whether there was a “British Way” of counterinsurgency during this period. For several decades following these conflicts, there was a common perception in Western militaries and even in academia that the British were exceptionally skilled at counterinsurgency due to their emphasis on minimum use of force and a focus on winning hearts and minds. Just prior to the war in Iraq, the British counterinsurgency manual even claimed that “the experience of numerous small wars has provided the British army with a unique insight into this demanding form of conflict.” However, following the less successful campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan, and a revaluation of the evidence in the original colonial cases, this notion of a uniquely successful “British Way” has been challenged.

One of the major new findings of the revaluation of these older conflicts, using new archival material, is that the British use of coercion against the population was far greater than previously believed. Although the type and level of coercion varied across the conflicts, one of the major goals of The British Way is to illustrate the trade-offs around the use of coercion and violence toward the civilian population by the British, but also committed by the insurgent factions.

Grant: Why did you feel this was the best way to tell the story with 4 separate games?

Stephen: I’m a political scientist in training focusing on Comparative Politics. One of the most interesting dilemmas in my subfield is figuring out how to develop generalizable theories while also respecting the unique aspects of specific cases. With these smaller British campaigns, I wanted players to be able to make comparisons about why British and insurgent strategy differed across the four conflicts. I hope this will drive players to ask questions such as: Why did British COIN use more violence against the population in Kenya than Malaya? How do clandestine insurgent groups operate differently from insurgents attempting to seize territory? How does the level of international attention alter British strategy across the four conflicts?

Each of the four games will have their own combined rulebook and playbook that provides historical background for that specific conflict. However, there will also be a multipack playbook that includes comparative articles drawing together major themes across the four games including: British COIN strategy, uses of coercion and violence, the insurgent challengers, and the impact of decolonization.

These are of course just the major overall multipack themes. Each game in the pack also has a couple of major themes about the specific conflict.

Grant: These conflicts cover the period between 1945 and 1959. Why did you settle on these dates and why not choose other conflicts?

Stephen: I chose these specific British COIN campaigns because they are the ones commonly cited as forming the “British Way” of counterinsurgency, particularly Malaya. These four campaigns also have the interesting advantage of occurring during the main period of decolonization and also the rise of attention to human rights such as the formation of the European Human Rights Convention (1950) that impacted British counterinsurgency, most heavily in Cyprus. Later British counterinsurgency has already been covered in The Troubles and A Distant Plain, although it would be interesting to see games on British counterinsurgency during the inter-war period.

Grant: The concept of a COIN multipack is unique. What other situations or stories do you see as good candidates for this concept?

Stephen: I think the multipack concept will work best when one picks conflicts that are fairly narrowly linked. One needs to be able to make reasonable comparisons across the topics and, from a production standpoint, the games need to be able to share some components, particularly the wooden pieces. Therefore, the topics should be linked geographically and fall within a fairly narrow time frame. This also helps with forming linking campaign scenarios which we’ve found during testing really help fill out the pack and address broader themes. I’m currently researching or working on multipacks (four player 2-packs and more two player 4-packs) using the following linking strategies:

- “Cross” Conflicts Multipack: Four different conflicts in the same region and time period. For example, civil wars in Latin America during the 1980’s (Peru, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Guatemala). This is the same style of pack as The British Way and lets one compare the similarities and differences across many thematically similar conflicts.

- “Within” Conflict Multipack: Several distinct parts of the same conflict. For example, 4-player depictions of fighting in both Tonkin and Cochinchina during the First Indochina War. A good two player 4-pack example would be different theatres of guerrilla warfare during the American Civil War. This style of pack is about juxtaposing significant variation in the type of warfare within the same overall conflict.

- “Legacy” Conflict Multipack: Different conflicts over time on the same map. For example, Soviet Afghan War followed by the transition to Najibullah to the rise of the Taliban. This style of pack is about illustrating how the legacy of conflict shapes a country and helps setup the next conflict. Factions may come and go but the conflict continues.

All of these different strategies of linking topics into multipacks are about providing players a comparative perspective on conflict. This approach will not work with every topic and many topics will be better covered by standalone games. However, my hope is that a series of multipacks might provide new ways for wargamers to think about conflict and help cover some topics that would be difficult to design or sell as standalone products.

Grant: Isn’t this new concept really just designing 4 new games and isn’t it more work? What strategies have you used to ease the design challenges?

Stephen: No, it’s actually just designing 4 ½ games since I also had to design a sub-game that links them together in the campaign scenario! I cannot really stress enough how much the double-dipping between my academic work and game design has eased this process. I had already extensively researched several of the conflicts in the pack for a working paper (and for several of the games in other packs I’m working on). I generally let my academic research guide the topics of my game design to make the workload manageable. Research for game design has also actually helped several of my current papers under review, so there are definitely benefits both ways.

However, there are several strategies for mitigating the challenges for anyone wanting to design a multipack. First, it’s essential to be disciplined about what conflicts you try to combine together. One major part of the research process is conceptually designing the pack itself before the individual games. Second, it greatly helps to do as much of the research up front as possible so you can identify the major themes for the overall pack and individual games that you need to cover. I’ve found this helps me avoid getting stuck or forcing a conflict to fit this format. It also helps with designing all the games with the others in mind so one can make sure you are emphasizing the unique differences of each conflict by tailoring the mechanics around the themes identified for each game.

Grant: How does this new multipack approach change the core COIN mechanics? What is the goal with this approach regarding these unique counterinsurgencies?

Stephen: The main changes to the core COIN mechanics for The British Way was altering the way two player COIN works. I streamlined the two player sequence of play designed by Brian Train in Colonial Twilight and changed victory to work off of an overall Political Will Track to reflect that these were really head-to-head challenges between the British and insurgents. There are also significant variations to the core COIN mechanics with the two more clandestine cell-based insurgencies in Cyprus and Palestine. Finally, I think the multipack really benefited from the linked campaign scenario and designing a macro game that covers four smaller COIN games required innovating from what had been done before in the series.

Grant: How has this new approach streamlined mechanics to quicken gameplay? What has been sacrificed in this approach?

Stephen: The new approach streamlined the sequence of play but mainly quickened the gameplay by focusing the games on only two players. In normal multiplayer COIN games a faction commonly only operates on every other card, unlike The British Way where they operate on every card. This removes a lot of the down time compared to multiplayer COIN games.

Of course, one sacrifice is that, by covering only two factions, the games have less of the rich multi-faction interactions and negotiations found in multiplayer COIN. This is one of the main reasons I switched to the Political Will Track for victory. Even though these smaller two player games lose that aspect of the multiplayer COIN experience, by translating player actions to shifts in Political Will, I could expand the different pathways to victory than the more abstracted (X+X) static goals common to the COIN Series (e.g. Opposition + Bases). In other words, I’ve tried to substitute some of the strategic complexity lost due to only having two factions by widening the available strategies. This game design decision was in part inspired by the different experiences I got from 7 Wonders Duel compared to the earlier multiplayer version of 7 Wonders.

Grant: How has the two-player sequence of play been modified? What do the changes improve or change?

Stephen: The two player sequence of play has been streamlined to help new players pick up the core initiative mechanics quicker. The new sequence of play also makes the trade-off around Events stronger as there is no longer an “Op Only” space. This alters the dynamics of the “double move” common to two player COIN games by adding more uncertainty about whether you can afford to carry out your multi-card plan. Playtesters have responded positively to the new change and the sequence of play has been incorporated into Fred Serval’s A Gest of Robin Hood with an additional interesting twist.

Grant: How does the new Political Will Track concept work and how does it determine victory?

Stephen: I’ve already briefly described the Political Will Track above but the general idea is that the insurgent factions are trying to drain British Political Will to pressure them to eventually leave on the insurgents’ terms. The British want to demonstrate success against the insurgency to raise Political Will and ensure a British determined exit from their colonies. There are actually two different styles of Political Will Tracks across the games. In Kenya and Malaya, there is a symmetric track with each side wanting to pull it to their side to achieve a minor or major victory. In Cyprus and Palestine, the insurgents have to wear down British Political Will to zero; otherwise, the British win at the end of the game.

Grant: What size are the boards for the games? How have these smaller footprints enhanced play?

Stephen: The game boards are all 17″x22”, so the same size as the board in Cuba Libre. All of these conflicts were fought over fairly small geographic areas compared to other games in the series. The smaller footprints ensure that the two factions are forced to interact and compete over the small numbers of spaces rather than being able to easily avoid each other by building up in their own sections of the board.

Grant: Can we get a look at each of the different maps?

Stephen: Sure. I should mention that these maps are all playtest art that was done by my partner, Jordan. She does the base map for all of my designs. Alongside finishing law school, she hopes to work on some of her own designs over the next year.

Grant: Each of these conflicts covered present their own unique challenges and opportunities. What is each games new focus and mechanics?

Stephen: To answer one of your earlier questions, the hardest part of multipack design is trying to briefly discuss four unique games in one interview question! However, I realize players are interested in knowing how the games are distinct in terms of theme and mechanics. I made it a priority to write an InsideGMT article on each of the four games to give players some background. Here are links to each of these on InsideGMT Games for The British Way:

Grant: What factions are represented in each of the games? How do the government and insurgent factions operate differently?

Stephen: The British are a faction in each of the games but have different tools to use across the four games. The insurgent factions range from communist insurgents in Malaya, militant nationalists in Kenya, and smaller and more clandestine terrorist organizations in Palestine and Cyprus. Each of the four insurgent factions operate differently. The MCP in Malaya is the most similar to communist insurgencies in existing COIN volumes but possess some tweaks to reflect their heavy reliance on only a segment of the population for support. The Mau Mau in Kenya struggled to collect arms and faced a severe power imbalance with the British but are able to leverage their relative size and the protection of the Mountain Jungles to contest British rule. The two clandestine terrorist organizations, EOKA in Cyprus and Irgun in Palestine, operate significantly differently from existing insurgent factions, relying on flexibility to evade the British and launch Sabotage and Terror attacks to drain British Political Will. Greater detail about each faction across the games can be found in our InsideGMT article series mentioned earlier.

Grant: How many turns are in each game and what was the criteria for your decision for each?

Stephen: All of the games have the same deck structure. There are three campaigns in each game that consist of 6 Event cards and 1 Propaganda card, shuffled in with the bottom 2 Event cards of each campaign. Therefore, each of the games have a typical length of between 16 and 18 Event cards. This is roughly equivalent to playing a 36-card multiplayer COIN scenario, given that your faction will get to operate on each of the cards rather than every other one. I thought these conflicts fit this length well because the military intensity and political complexity of each is significantly lower than Vietnam, Algeria, or Afghanistan. In addition, these conflicts were not as long as some of the other games covered previously in the COIN Series. The shortest conflict is Palestine which only covers about two years (1945-1947). Even though Malaya (1948-1960) and Kenya (1952-1960) were significantly longer, the games focus on the most intense period where the insurgency was going to be won or lost: 1948-1954 for Malaya and 1952-1956 for Kenya.

However, given Malaya was longer and higher intensity than the others, there is an optional Extended Malaya scenario that adds 2 Event Cards to each campaign for a total length of 24 Event cards.

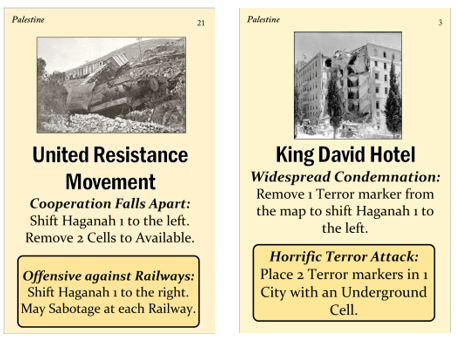

Grant: As you mention, Events are a major focus of the games. How many cards does each game have?

Stephen: Each game comes with 32 Events. You will use 18 Events each game, unless playing Extended Malaya, and set 14 Events aside. This helps add variability to each play while also letting us provide more history. By narrowing the number of Event cards, it forced me to work hard at deciding what were the most important events and also the ones that best illustrated the major themes of each game.

Grant: How long did it take to create these events? How similar are they across each game?

Stephen: I do all the research and conceptualization up front before assembling a prototype and I usually have a list of Events from the research. I tailor the Event cards based off of the history and try to link them to the other major mechanics in the game so the Event cards across the games are fairly different both thematically and mechanically. When Events have similar effects or theme than that is usually because British or insurgents were doing something similar across the conflicts that I want to draw players’ attention towards.

Grant: Can you give us a few key examples of cards that deal with the theme of each game?

Stephen: I’ll do this step by step for each game focusing on one of the major themes (most games have around three major themes I want to convey):

Palestine: A central theme of Palestine is the role played by the larger more moderate resistance organization, Haganah, during the Jewish insurgency. Haganah begins the game allied to Irgun (the player faction) as part of the United Resistance Movement after WWII, but historically ultimately broke with Irgun over their use of brutal terror attacks that resulted in high civilian casualties, as occurred at the King David Hotel Bombing.

Malaya: One of the major themes in Malaya is the British use of population concentration to assert their control over the insurgent support base through the use of “New Villages.” This strategy consisted of relocating Chinese squatters into fortified villages to deny the MCP access to the population and also provide benefits to the population to eventually shift them towards supporting the counterinsurgency efforts. When the British felt that an area was sufficiently secure, they would lift the restrictions imposed by New Villages declaring it a “white area” free of MCP activity.

Kenya: A major theme in Kenya is the British use of mass repression to isolate the insurgency from the Kikuyu population of the Central Province region (have you started identifying a pattern yet in British COIN?). Although these strategies weakened Mau Mau supplies, they also sparked controversy back in Britain led by the Labour Party MP Barbara Castle over their brutality.

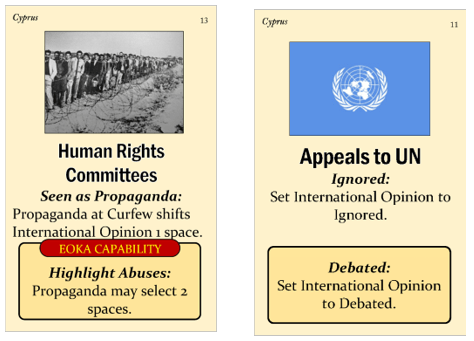

Cyprus: Cyprus is the latest conflict in the pack, starting in 1954. A major theme of the game is the rising international pressure for human rights. The international dimension put significant pressure on the British and affected their decision making about tactics. Cypriot lawyers tried to raise cases of human rights abuses, and the Greek Government consistently raised the issue of Cyprus at the United Nations.

Grant: How can players string each individual game together for a grand sweeping experience? What has been the feedback on this approach?

Stephen: The game comes with an “End of Empire” scenario that lets players link the four games into one broader campaign scenario. The scenario adds additional rules for a campaign scoring system, Imperial Prestige, a deck of decolonization random Events that add new trade-offs, and a Colonial Policy decision the British declare during each game. The feedback has been very positive for the campaign.

Grant: What are you most pleased with about the design?

Stephen: I’m actually most pleased about the “End of Empire” campaign since I didn’t initially plan to include it, but it turned out to be a nice way of tying all the games together. I’m not sure I will design a multipack without a grand campaign scenario going forward.

Grant: What has been the experience of your playtesters?

Stephen: I’ve been incredibly fortunate to have very helpful playtesters who have given detailed feedback on clarity and asked useful rules questions. We were pleasantly surprised by how many of the playtesters already found the designs polished when we opened up for general testing. It has been incredibly interesting to also learn how many of our testers have a personal connection to the conflicts in the pack, whether through a relative or being born on related military bases. There are a lot of playtesters that will be acknowledged in the game, but I wanted to highlight two now: Jon C. conducted an enormous number of tests, including a particularly amusing campaign scenario with me, and demoed The British Way for us at GMT’s Weekend at the Warehouse; and Gordon J. crafted very nice print and play copies of all the games and published pictures and write-ups over on BGG. These games wouldn’t be possible without our playtesters.

Grant: What other designs are you mulling over?

Stephen: I already previewed some of the next multipacks I’m working on in a question above, so I’ll focus on some non-COIN designs I’m considering in the next few years. I’d like to work on games that are centred around different types of political conflict in Comparative Politics, a major subfield of political science, such as social movements, democratic transitions, and how civil wars begin. Although I appreciate the rise of more political topics in the hobby, I think we can push for further diversity in the types of conflict modelled beyond purely military depictions.

That being said, I’ve been mulling over a few more military oriented games as well. I’d like to work on something at the Corps level in Vietnam that focuses on the unique features of each Corps zone in Vietnam, highlighting more macro resource control and strategy than operational level games like Silver Bayonet, but also giving a more military focused depiction than the macro political and socio-economic simulations like Fire in the Lake. This is inspired by a combination of my dissertation research and playing Volko’s Levy and Campaign series, but I assure you that for better or worse there will not be any sleds in Vietnam.

Thank you so much for your time in answering our questions so thoroughly and with such context to help us all better understand the intricacies in this entry into the COIN Series. I must say that I have not anticipated a COIN Series game as much as I am The British Way after reading this. We have also made an offer to Stephen to host a series of Event Card Spoiler posts on the blog for the game and I hope that he accepts.

If you are interested in The British Way: Counterinsurgency at the End of Empire you can pre-order a copy on the P500 game page from the GMT Games website at the following link: https://www.gmtgames.com/p-945-the-british-way-counterinsurgency-at-the-end-of-empire.aspx

-Grant

I am SO looking forward to these!

Great work Stephen, and I am glad that my work has been helpful to you.

– Brian

LikeLiked by 1 person

I would like to ask a couple sincere questions without sounding antagonistic toward the design. Maybe the designer is reading the thread and will respond…

First, is it a misconception that this design is meant to be an Intro to COIN approach to the series, primarily intended to coax newcomers to the series? I’ve only dabbled with COIN (two titles on the shelf), but the early coverage I have read about the game (smaller decks, smaller footprints) gave me that initial impression. Admittedly, a smaller map does not automatically mean a less interesting game to the experienced COIN player (e.g. Cuba Libre, a game that still seems to be well liked by COIN players, even to this day.)

Second, what do you think the real appeal will be to experienced COIN players, beyond the new theaters of conflict, and the fact that this will be only the second game in the series (correct me if I’m wrong) that is purpose-designed for just two players. In other words, what about The British Way is going to attract the established player with a sense of, “yeah, I have several COIN games, but I reeeeallly need to have this one too” ? There’s been talk over the last few years now about COIN market saturation, but I remain impressed that the series seems to have an Energizer Bunny lifespan.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the questions. I’ll try to answer them as completely as possible given we’ve gotten these before in other places so posting them here is very useful for us.

I would say part of the intention of the first multi-pack is for a better intro to the COIN series. I was actually thinking about making a volume that was more accessible for classroom use when I first designed TBW. I think three things makes it a good 2p Intro: 1) We’ve streamlined aspects of the 2p experience to make things such as the SoP and Victory more legible for new players. 2) As you note, the maps are smaller and there are less pieces than many of the larger COIN volumes. 3) All three games play around 60 minutes once you know what you’re doing. We’ve found from playtesters that if you’re fast then you can play some in a little under an hour but even if you’re slower it will still be under 90 minutes. For many new to the series, this is a more realistic game time than even a full game of Cuba Libre. However, for those wanting a longer experience, the pack also offers a campaign scenario with additional components and rules that lets you play through each of the 4 games in a linked scenario.

I should also note that we have had many playtesters who are completely new to COIN. They have enjoyed the games as their first volume even if they still needed to get used to some general series mechanics (e.g. Capability Cards). We also have veteran COIN testers who have played every COIN volume including some not released yet. They seem to also enjoy TBW for the new way of handling 2p and its ability to give a quick COIN fix.

I think there are three features of The British Way that cannot be found in other current COIN products besides the specific conflicts:

1) It is smaller footprint and more accessible to new players, but the game still comes with significant content for veteran players. Given its multi-pack nature, you get 4 COIN games each with their own rulebook and unique features (unique from each other and other volumes). More importantly, you also get a volume that allows easier strategic and educational comparisons to be made across the games as you travel across the stretch of the former British empire.

2) Related to the first point, no COIN game offers an additional linked campaign scenario (unless you count FitL with FoS or SoD but the factions don’t change). With additional cards and mechanics, you gain a new gaming experience where players need to balance doing well in the campaign with the needs of each individual game. Unlike in most 4 hour COIN scenarios, you’ll need to adapt yourself to each new setting as the campaign progresses. I imagine most veteran players will play the “End of Empire” Campaign Scenario solo or with a friend each time it comes off the shelf. I should mention every new multi-pack in the works comes with a different style campaign experience. The next pack, in addition to being higher complexity than TBW and thematically focused on insurgents, will feature a Campaign where players play two games linked side by side with each affecting the other which will also hopefully allow team play with one insurgent and one government on each side.

3) Two of the games (Cyprus and Palestine) in the TBW have new Counter-Terrorism mechanics which means both the insurgents and COIN factions operate unlike factions in any other volumes in the series. Many core COIN concepts like Control, Support/Opposition, Resource Management have been replaced with new mechanics to represent the small clandestine groups. Therefore, veteran COIN players will have two completely new experiences in addition to the new unique mechanics in Malaya and Kenya.

Finally, I think COIN’s Energizer Bunny lifespan is less surprising if one views the series as a set of core mechanic more than a game series (i.e. more “Card Drive Games” as a mechanic than the No Retreat series for instance). There are already a lot of CDGs with even more coming out that offer new innovative mechanics and cover neglected topics (e.g. Shores of Tripoli or Brotherhood and Unity). In addition, COIN often has covered topics you cannot get a wargame on anywhere else (especially if you don’t count magazine or PnP games). Despite Malaya being one of the most important cases of Western counterinsurgency, you can currently only get a simulation of it in TBW as far as I’m aware. One general principle I have with the multi-packs, is that each one should have at least some conflicts that have not been covered anywhere before.

Let me know if you have anymore questions.

Stephen

LikeLiked by 1 person

What you describe, especially the inclusion of a linking, campaign-type scenario, sounds like the game will have a very “Swiss Army Knife” kind of utility to players of varying COIN interest and experience. Seeing the game already at 1000+ preorders seems like there is solid interest beyond just the COIN curious.

I wish you success with the product, and thanks for taking time to answer questions. Very interested to see how the game is received by COIN players.

LikeLiked by 1 person