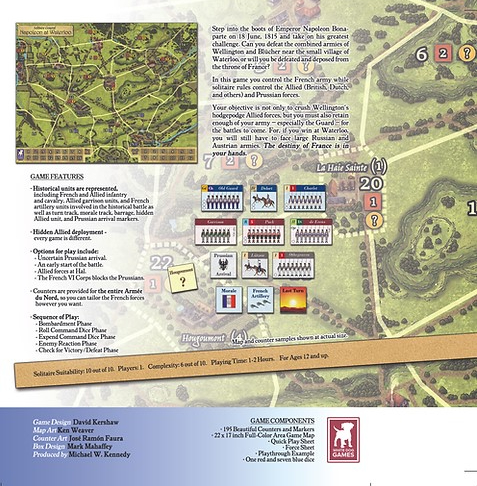

I love well designed solitaire wargames and have played many of them over the past 8 years or so. My first experience with a White Dog Games product was with Solitaire Caesar designed by David Kershaw. This was a very good game that I played dozens of times over the pandemic when I was locked away at home for those 4 months. Since I have played more of his games including World War Zeds: USA, Irish Freedom, The Night: A Solitaire Zombie Attack Board Game and The Mog: Mogadishu 1993 to name a few. David’s games are always very engaging, interesting and well put together and create a very good play experience. Recently, White Dog Games announced a new solitaire hex and counter wargame set on the Waterloo battlefield designed by David Kershaw called Solitaire General: Napoleon at Waterloo. I purchased a copy from Blue Panther while attending Buckeye Game Fest and have only unboxed the game at this point and have yet to play. But I did reach out to David to see if he would share some information about the design and he was more than willing to accommodate the request.

Grant: First off David please tell us a little about yourself. What are your hobbies? What’s your day job?

David: Wargaming! That’s the answer to quite a bit. To be more detailed, I am 53 and was made redundant at the end of last year (2023) from my day job, which was working on international payment formats for a bank in Northern Ireland where I live. So, my day job is presently designing games, which are mostly wargames and presently exclusively published by White Dog Games. I have a regular gaming group I play every couple of weeks or so with, mostly miniatures wargaming, and a couple of other friends I play less frequently with, mostly Games Workshop games.

I have 2 children (teenagers, they are 19 year old twin boys) with autism so I get weekly respite for me and my wife on Thursday evening, which means that we are working our way through Belfast’s restaurant scene. My other child, the eldest, is not autistic and has just finished university. To my delight her boyfriend is also a wargamer!

For non-wargaming hobbies, I enjoy a bit of cooking at home, presently obsessing with sourdough. To stay healthy I do some running. I managed a half-marathon a couple of years ago but then hurt my Achilles and have only just managed to get back to 5KM. I have 2 pampered rescue dogs (lurchers) and 9 equally pampered chickens.

Grant: What motivated you to break into game design? What have you enjoyed most about the experience thus far?

David: I had always tinkered in game design from quite a young age. I remember designing a hex & counter game about the 1945 fall of Berlin when I was 16, and have created simple designs with friends as I grew up. For the last ~20 years though I have been mostly playing miniature wargames with a group once a fortnight or so. Miniature gaming is very open to house ruling: If we are playing a set of rules it is very unlikely that they will survive intact without at least a few house rules – sometimes even a complete re-write. This is not just me, but the others in the group are involved in this process as well.

Without doubt the most enjoyable part is researching the history. You can go down some really odd paths. For example, for The Mog board game, which is about the UN actions in Mogadishu in 1993 (including “Black Hawk Down”), I ended up getting access to and reading a lot of UN reports, which have a surprising amount of dry humour in them.

Grant: Where did your start to design come? How has your design process evolved over the years from your start?

David: The real impetus was becoming a father 22 years ago. Being unable to get out and do gaming I started making my own designs. The first was a quick WW2 Eastern Front game – I later got into programming and this became the first ever wargaming app on Android devices. After that I developed Solitaire Caesar, which depicts the entire progress of the Roman empire from the foundation of Rome to the fall of Constantinople some 2,000 years later. This title got the attention of White Dog Games who approached me about publishing it. They did and were happy, so I started designing in earnest. Sometimes my own designs, sometimes from a brief, and sometimes as developer for another design that needed help.

My design process has mostly evolved to see what elements from miniature gaming will fit well into the world of board gaming.

Grant: What is your upcoming game Solitaire General: Napoleon at Waterloo about?

David: It is a solitaire game of the 1815 battle of Waterloo where “Napoleon did surrender”, as ABBA slightly inaccurately sang. In the game you get to play Napoleon. In the rest of the interview, I’m going to abbreviate the game as “SGNAW”.

Grant: Is this the first volume in a new series of games? What other Napoleonic battles might this system best match?

David: It depends. I did a 2-player game on the battle of Albuera that was well received and got excellent reviews… but it did not sell very well. It was supposed to be the first in a series, but the bad sales meant that a follow up (to have been Marengo) did not proceed. So, if SGNAW does well then follow-ups are possible. As a solitaire game, you need a fairly static battlefield where the enemy really just reacts. Good battles that fit this are Borodino (as Napoleon), Eylau (as Napoleon), Leipzig (as the Allies), Vimeiro (as the French), Salamanca (as Wellington) and many more, so there is plenty of choice.

Grant: Why was this a subject that drew your interest?

David: Ironically, it didn’t. I would not have designed a game about Waterloo without getting a shove from White Dog. A designer had recently jumped ship from them, taking all their games, one of which was about Waterloo. White Dog felt they really needed a Waterloo game and so approached me to make one. I do know a fair bit about the battle as I have played it a few times using miniatures – it is a difficult battle to simulate because any French player knows that they are against time and invariably throws in their best troops (the Guard) as soon as they can to break the Allies before the Prussians ruin things. So that got me interested – the fact it was a solitaire game also added another dimension I could play with: uncertainty.

Grant: What is your design goal with the game?

David: The overriding priority was: You must be able to make the same decisions Napoleon made, even with hindsight, and these decisions have to have a chance of succeeding. Equally, can the Allies/Prussians, even though simulated, provide a challenge and give Napoleon the same problems he faced on the day of the battle.

The idea was to step into the mind of Napoleon and make decisions for him – this is where the command dice come in.

However, the key part of the design was uncertainty: This came from a description of the battlefield from the point of Napoleon. To paraphrase: Napoleon knew that the Allied army was there, but it was all obscured behind buildings, slopes and dense vegetation. He didn’t know what was before him or where it was. Therefore, the entire allied army starts the game hidden. When the French start to attack, capture areas, or the Allies have to reinforce, then parts of the Allied army are revealed.

This is what makes the game fresh and offers a new challenge every time. You could launch an attack and be met by indifferent Dutch/Hanoverian troops; or you could run into the British Guard backed up by Heavy Cavalry. What you do then is up to you, and will definitely affect how you fight the battle. In the real battle, D’Erlon’s I Corps attack was probably meant to break the Allied left and win the day. However, although it did well against the mixture of British/Dutch/Hanoverian troops, the British Heavy cavalry were in that spot and launched a devastating counterattack. The rest of the battle was Napoleon reacting to this initial setback and looking for a way to win.

This initial part of the battle is in the game’s walkthrough PDF, which you can download for free from the files section of the game’s page on BoardGameGeek.

Grant: What other designs inspired you in making this game?

David: This might sound odd, but the central command-dice mechanism comes from a tank skirmish miniatures game by “Too Fat Lardies” (a well-known design group in miniature wargaming) called What a Tanker!

In What a Tanker you control a single tank and roll 6D6 to determine what you can do with it in a turn. Each face of each die allows a single action – so, for example, you need a 1 to move, a 2 to aim, a 3 to fire, and so on. On the other hand, one of the testers of the game said that the command-dice mechanism in SGNAW reminded them of the action dice in War of the Ring, but that is unlikely to have inspired me as I have never played it.

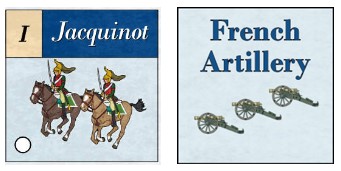

The first thing you’ll notice in the game is that infantry look different from cavalry. Infantry counters are rectangular while cavalry are square. As well as aesthetics (infantry in line are wider than they are deep), this also serves to keep the two types distinct. This comes from my earlier game, Albuera 1811, which is two-player, but it also has differently shaped counters.

Grant: What sources did you consult to get the details correct?

David: The main one was The Waterloo Companion by Mark Adkin.

This is a glorious coffee-table book packed full of maps, illustrations and a detailed order of battle. I wanted the French set-up to look like it does in that book and it does.

I am a bit of a Napoleonic Wars buff and it’s my favourite period to wargame so I have a fair bit of background information I can draw on from years of experience playing, visits to battlefields (including Waterloo) and, of course, so many books! I used a variety of different sources to check details and get information for the optional elements (such as other French forces). There are some really obscure things that you spend longer than necessary trying to figure out – for example, the commander of the Brunswick cavalry contingent, Cramm, was killed before Waterloo at Quatre Bras. I spent a ridiculous amount of time trying to find who took over, but drew the line at learning German to check those sources. I eventually went for Pott who commanded a sub-element. This isn’t needed for the game, it’s just chrome!

Grant: What elements from the Battle of Waterloo and the Napoleonic Wars did you need to model in the design?

David: My initial thought was: I need to be able to model these three things:

- D’Erlons I Corps attack – it had to have a chance to succeed, since that was what it was supposed to do.

- The counterattack of the British Heavy cavalry – I needed a small force of heavy horse to be able to trash a greater number of infantry. Conversely, I also needed this to not be the case since when the French tried it with their mass heavy cavalry assaults they failed.

- Reille’s attempt to capture Hougoumont: A whole corps held up by a brigade.

From the Napoleonic Wars I needed to reflect the power and weakness of cavalry, as well as their different types. A lot of the cavalry is light and it has little chance against infantry – unless those infantry are disordered, then it can really make a mess. Artillery was trickier, especially in a compact battlefield like Waterloo where there were also a large number of rifle armed Allied troops who could fire at much longer ranges than the musket armed French. I therefore abstracted the Allied artillery to a separate bombardment phase, but I kept the French artillery as deployable units, so that a Grand Battery could be formed, if desired.

The hardest part was defensible terrain. Hougoumont, La Haie Saint, and Plancenoit held out for hours. Initially I just gave this terrain a bonus in combat, but this did not match the open-ended nature of combat in open terrain and the defensible terrain fell easily. So instead I made fighting in defensible terrain more limited – this totally changed the nature of combat for it and also made it more of a gradual “meat-grinder” that I wanted to see.

It is also interesting to see how the design affects actual player decisions. If you want, you can ignore Hougoumont and send Reille’s corps up the flanks of it against allied positions in the open. But this means that you will be constantly getting hit by fire from Hougoumont, and if it reinforces it can certainly launch nasty attacks in your rear – meaning you need to leave valuable troops to guard against that. In the real battle, Napoleon wanted Reille to feint against Hougoumont to keep the Allies unsure and their large reserves on that flank distracted. Reille succeeded in this task, although he did get a bit carried away with trying too hard to actually take Hougoumont. Another factor which is not mentioned in any sources, but is certainly something that came up in playtest is that if the forces at Hal arrive, they will arrive on Reille’s flank. Keeping Reille intact is an important guard against that eventuality.

Grant: As a solitaire game how does the AI function?

David: The AI’s main role is to reinforce weak areas and launch opportunity attacks.

Weak areas are reinforced in two parts of the game: during combat and also during the AI’s turn. There is also an advance phase where rearmost troops can come forward, or unoccupied areas can be reoccupied.

Both infantry and cavalry counterattacks can be launched. The Prussians are more likely to attack, as are the British Heavy cavalry. They are also more likely to attack “morale areas” (areas which have a morale value), which are an important objective in the game since you win the battle by reducing your opponent’s morale to zero through eliminating units and capturing morale areas.

Grant: What goals drive the AI?

David: For the AI, the goal of the early part of the battle is simply holding on for survival, so reinforcement and recovery are a priority. The AI will launch attacks to recapture lost morale areas though (e.g. if you capture La Haie Sainte, the AI will probably try and take it back). And the cavalry are especially gung-ho if they sense weakness.

When they turn up, the Prussians are more dangerous. They arrive with nothing to defend and plenty to attack, and they will attack. If you are not careful at this stage you can easily lose the battle if the Prussians find that the French right and Plancenoit are poorly defended.

Grant: What type of experience does it [the AI] create?

David: As this is a boardgame, the AI is transparent in nature, rather than a black box. So you can see what it is likely to do, and adjust your forces accordingly. However this does not always work due to accumulation of actions during the AI’s turn and the knock-on effect of each one on following actions: What you thought was a powerful force can be reduced by artillery and then battered by waves of cavalry attacks before an infantry assault finishes it off.

The experience is therefore one of risk management followed by blind panic!

Grant: What is the games scale? Force structure of units?

David: The game wanted to stay true to the forces used in the battle, so I really wanted to use historical units. These provide a lot of the flavour of Napoleonic warfare with their different uniforms – especially on the Allied side with its multiple nations.

On deciding the scale you can see in the battle that while the French tended to keep their divisions (about 4,000 soldiers in a division) together, the Allied divisions were often split up between different parts of the battlefield. This made me think that division level (1 unit = 1 division) might not work very well, so I went to brigade level (French divisions usually had 2 brigades while the Allies were 2 or 3 with the odd lone brigade too). Even this is not granular enough as there were individual battalions garrisoning various features, so I did add some garrison units as well for these.

This meant that an infantry unit represented about 2,000 soldiers of a brigade. For cavalry, the French “division” tended to be the same size as the Allied “brigade”, so the units are about 1,000 horses.

Grant: What is the anatomy of the unit counters?

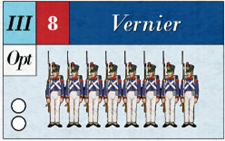

David: I wanted to keep the system as streamlined as possible, so counters only have one combat rating. The counters are also double-sided: full-strength and damaged sides. They range from +3 at full strength (Old Guard) to -3 on the damaged side (the weakest cavalry). Most infantry are +1 full strength and -1 damaged. Cavalry are mostly +0 full strength (most cavalry are light, the heavier/elite cavalry range from +1 to +2) and -2 damaged. Cavalry counters act differently from infantry, which is why they are a different shape – a good visual reminder.

The other key feature on counters, which only really matters for the French, is a division and corps designation. These are also colour coded to make things easier.

Of course, the counters also have wonderful artwork on them, showing the uniforms of the troops and a historical designation too. A lot of wargamers care about these details – it is far more fun to say “The Union Brigade just rode down Charlet’s infantry” than “cavalry unit A beat infantry unit B”.

Examples: This French infantry unit belongs to the III Corps (blue highlight), 8th Division (red highlight).

The full-strength on the front is two white dots, giving it +2 in combat. The name “Vernier” is for historical interest only. “Opt” indicates this is an optional counter.

Below shows the back (damaged) side of an Allied unit. Note it has fewer troops and a red bar below the name:

It has one red dot, so it gets -1 in combat. “KGL” is for historical interest only.

Cavalry are square counters, as are artillery:

Grant: How is the game map laid out? Why was area movement your chosen method to tell this story?

David: The early design had a very simple map with just the flanks and reserve areas, plus some boxes for the redoubts at Hougoumont, La Haie Sainte and Papelotte. I am reminded of Pete Belli’s design One-Minute Waterloo which only had 9 hexes and 9 counters which he felt was enough to tell the story adequately – iirc distilling the game into a single decision: when/where to commit the Guard. Since SGNAW is a solitaire game I wanted the scope to be sweeping in nature, so areas were chosen as they can be tailored to the details of the terrain and the needs of a solitaire game better than hexes which are rather rigid and unforgiving. For example, La Haie Sainte is a tiny feature and if the game was in hexes this feature would likely drive the scale. Using areas, I can leave La Haie as a small feature and retain the large dramatic ridges to either side of it – and have the large dramatic corps-sized assaults in them that the battle deserves.

Grant: What advantages does this format give you?

David: Primarily it controls the look of the battle – you will be able to advance whole corps, or detach divisions for specific tasks, and they look great as they go about their business. But this also means that the flow of the battle tends to be grand attacks with large formations that you (and the enemy) will feed more troops into. This is what Waterloo should be about!

It also very much assists in controlling the way the AI behaves. A limited number of areas gives you less to check when seeing what the AI might do.

Grant: What are the different areas shown on the game map?

David: Although they all look different there are technically really only 3 as far as terrain goes: Open, open with a ridge that blocks long-range artillery, and close terrain (the farms and woods). However, there are further details, such as morale numbers and stacking limits in close terrain.

Grant: What are the purpose of the red and blue numbers in the areas?

David: These are morale points. Red are for the Allies and blue are for the French. The way you win the battle is by reducing the enemy’s morale until they give up and retire. The two ways to do this are eliminating infantry (cavalry were expected to die gloriously, so they don’t affect morale) and capturing the enemy morale areas. Some areas are worth more than others – the outer farms (Hougoumont, etc.) are not worth as much as the key positions behind them.

Grant: What are the different phases of the game?

David: You, the player have the first couple of phases, which are bombardment with artillery and then moving (or rallying) units with command dice, including sending them into combat.

Then the AI player reacts. It, too bombards, then it reinforces and may launch counterattacks.

Finally, there is a quick check to see if the game has ended before a new turn starts. There are a fixed number of turns in the basic game, but of course there are options to change this to either add uncertainty or start the battle earlier.

Grant: What is the purpose of the Command Dice?

David: These are the heart of what you can do as a commander. You roll 7D6 (seven six-sided dice). Each face of each dice allows a different action. 1 and 2 allow infantry to be moved, 3 is for cavalry, 4 is for artillery, 5 is for rallying or activating the guard. 6 is “wild” and you can change it for any other face. You can also save dice for a future turn, if you are planning something big.

You may need to do this because combinations of the same face allow greater actions to be achieved. A single infantry face (1 or 2) allows you to move a single infantry unit (brigade). But two of them allow you to move a division and three of them allow you to move a whole corps.

I wanted these dice to be the mind of Napoleon. For example, you roll a lot of three’s and he is clearly thinking about the cavalry.

Grant: How does combat work in the design?

David: All combat is oppositional dice: each side rolls a D6, adds their modifiers, and a winner is determined. This was chosen as it produces the same normal curve as a single 2D6 roll, so extreme results are rarer than common ones, but I think it is more fun to “dice-off” two sides against each other!

Napoleonic combat is a particular love of mine. My main hobby in wargaming is miniatures, and within that I play a lot of Napoleonic with a gaming group. Napoleonic combat is all about the strengths and weaknesses of the 3 arms of the era: Infantry, cavalry, and artillery (cannons).

Infantry can generally beat cavalry – unless they have been disordered beforehand, such as by other infantry or artillery fire. Against other infantry they really need support to prevail. The game simulates this by giving infantry +1 in combat per support. Defenders get +1, so you will need 2 supports (the maximum allowed) as the attacker to get an advantage over the defender – which is the 3:1 attacker to defender ratio that is often mentioned as needed for an attacker to prevail. Obviously, other factors come into play, such as some units being better than others, or being damaged.

Artillery is good at breaking up formations to make the job of attacking infantry or cavalry easier. In SGNAW artillery is largely abstracted to the bombardment phases, but there is the ability to use horse artillery which could be very nasty on dense formations, such as infantry in square.

Cavalry are a bit of a one-shot weapon. Once you launch them they will either do very well or else end up disordered and not much use. This is why the cavalry in the game are so weak if they get damaged (disordered). Against other cavalry, the same rules about supports come into play as for infantry.

Cavalry versus infantry though needed a different approach. One of the big events during the battle was the charge of the British heavy cavalry which shattered D’Erlon’s corps attack. The cavalry were outnumbered hugely in this, so I needed a different approach. Basically, if there are no rival cavalry to counter them, cavalry fight infantry 1 on 1 – no support for the infantry, who are assumed to be desperately trying to form squares. If the infantry win then the cavalry will become disordered and useless. If the cavalry win though, they have the ability to keep going, smashing through more and more enemy infantry until they are stopped or the infantry are no more.

Grant: What determines when the Prussians arrive?

David: In the basic game they arrive on a set turn. However, their rate of arrival is randomized and so is their area of arrival, which also varies between the three Prussian corps. Optional rules allow you to make the Prussian arrival uncertain, and there is also a random event that can delay them. There is also the option to detach Lobau’s VI corps to try and block the Prussians away from the battlefield in the forests to the East, which is risky.

Grant: How is victory achieved?

David: It’s not as simple as simply beating Wellington. You can do this, but this will be of no use to Napoleon if you suffer heavy casualties. Napoleon needs the army in decent enough shape to fight the other enemies: Austria and Russia had large armies that were bearing down on Paris.

There is also the political aspect. The book Napoleon’s Immortals (Andrew Uffindell) inspired me most here to see that the Imperial Guard were critical to Napoleon’s power – they were not just a group of elite troops, they were elite troops answerable to Napoleon alone. By 1815 they had swollen from a small guard to a large corps. France in 1815 was not very secure and Napoleon’s hold was tenuous. He needed the Guard as a personal chip he could play to face down opposition. So, the game also requires that you keep the Guard as intact as possible.

Grant: What different levels of victory are there?

David: There are three: Win the battle. Keep the army viable. Keep the Guard strong. If you achieve all 3 of these then you have done the best possible. Win at only 2 of them and you’re probably in trouble. Only winning one is delaying the inevitable, while losing all 3 is the historical outcome: total defeat and exile.

I’ve written up an analysis of all the possible combinations so players can see what a historical outcome of their specific victory level is likely to be. For example:

The battle is lost or drawn, the army is shattered, but the Guard are intact. Napoleon retreats back to Paris and sets about raising another army. This is likely in vain as other field forces are gradually crushed or dispersed as the Allied forces advance. Maybe Napoleon escapes to exile in this scenario?

Grant: What optional rules and alternative scenarios are included?

David: Quite a lot. To keep it brief: Uncertain Prussian arrival, Intervention of the forces at Hal, Grouchy, some other French units, an earlier start, uncertain ending, random events, and more. There are also ways to change the difficulty of the game.

Within each of these there are also different combinations. For example, the forces at Hal historically did not hear the battle and were not involved. Options for Hal include their arrival, the presence at the battle from the start, and them being a different composition.

Grant: How do these change the game? What do you feel the design excels at?

David: Fundamentally I wanted the game to function not just as a game but also as a “sandbox” so that you, the player, can try different ideas and forces to see what the outcome might be. To that end, the entire French Armée du Nord is included, not just the bit that fought at Waterloo. You could, say, start Waterloo with Vandamme’s III corps instead of Reille’s II corps, if you wanted. Or any other combination you can think of. All three Prussian corps that fought at Waterloo are also included in their entirety (even though a lot of them never made it to the battle), as is the entire Allied army, including the divisions that were detached to guard against a flank attack at Hal.

Grant: What type of experience does the game create for the player?

David: I hope it is an exciting one as the Allied forces are gradually revealed and your strategy has to be modified to reflect this. There will be tense battles swinging back and forth – all the time you will be thinking about keeping your troops fresh, and you will be careful about committing the Guard. Along with this you are going to get some rolls of the command dice that are not what you want and may well also affect your play. And don’t forget the Prussians…the clock is ticking!

Finally, when you have tried different ways to win the battle (and it can be won, although winning the game is far harder) you can then start to explore the myriad of options.

Grant: Who is the artist for the game? How has their work connected with your design to create an improved theme?

David: José Faura did the art. He has done a lot of work with me – he’s incredibly quick and responsive while keeping the detail good. Meanwhile, a new artist did the map – Ken Weaver. Ken had previously done a fan-art map for my game The Night about the Night of the Living Dead. Bit different from Waterloo, but me and White Dog gave him a chance and he went for it, producing a beautiful map.

Grant: What other designs are you currently working on?

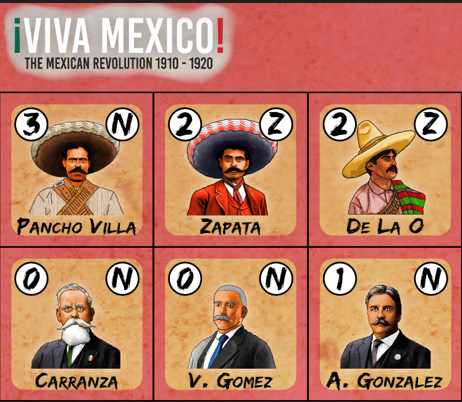

David: The next game will be Viva Mexico, which is a solitaire design on the Mexican Revolution of 1910-1920. It is similar in concept to Irish Freedom (which was about the Irish War of Independence and Civil war) in that you change sides as the game progresses. There is a lot more of this though in the Mexican Revolution, plus a cast of hugely entertaining characters that exist as counters in the game: Pancho Villa, Emiliano Zapata, and many others.

After that, I have a few in planning: the Haitian Revolution of 1791, Shiloh 1862, a WW2 air combat game, the Anzacs at Gallipoli, a sequel to The Night, a nuclear war game.

Thanks David for taking the time to answer our questions. I have appreciate your games for quite a while now and played many of them and always appreciate the approach you take to their design and especially to their playability and fun. I very much look forward to playing my copy of Solitaire General: Napoleon at Waterloo soon.

If you are interested in Solitaire General: Napoleon at Waterloo, you can order a copy for $50.00 from the White Dog Games website at the following link: https://www.whitedoggames.com/waterloo-solitaire

-Grant