A few summers ago, while attending WBC in Pennsylvania, we met and played a game with Alex Knight (in case you were wondering the game was Nicaea from Hollandspiele). He is an aspiring new designer, with a quick mind and rapier wit, and we really enjoyed meeting him and I could see great things for him upcoming at the time. He then released his first game called Land and Freedom from Blue Panther that cover the Spanish Revolution and Civil War. The game is called Land and Freedom: The Spanish Revolution and Civil War and we very much enjoyed our plays of the game. He has since announced a new game called Hammer and Sickle: Hunger and Utopia in the Russian Civil War, 1918-1921 from GMT Games and we reached out to Alex to get a feel about the game and some more information to share with you here on the blog.

*Keep in mind that the design is still undergoing playtesting and development and that any details or component pictures shared in this interview may change prior to final publication as they enter the art department.

Grant: Alex thanks for coming back to the blog. How have you felt about your published game Land & Freedom?

Alex: Thanks for having me back. I’m thrilled by all the positive responses Land and Freedom has received! Being my first published design, from a small print-on-demand publisher like Blue Panther, I had no idea what to expect. For the game to garner the attention of so many articles, podcasts, academic talks, etc. was unforeseeable. I’m also pleased about the Spanish-language edition coming out, and that a new upgraded English edition will soon be in the works as well! Winning the SDHistcon Summit Award is the greatest honor of all, because it perfectly encapsulates what I’m trying to do in broadening the historical games hobby to new audiences.

Grant: What have you learned from that experience that will make you a better designer?

Alex: Since most of my current designs began long before Land and Freedom was published, I would say the biggest thing I’ve learned since the game was published is the importance and difficulty of extreme precision in writing board game rules. I always keep written rules of my designs and prototypes and revise them throughout the playtesting process. But even after revising and re-revising the rulebook to Land and Freedom before the publishing date, we still needed to release a newly revised version of the rulebook within a couple months of the game coming out, with various clarifications and additions. And even still, players submit various questions on Boardgamegeek that I realize aren’t sufficiently explained in the rulebook, or could be made clearer with illustrations. Obviously, it’s impossible to write perfect rules that 100% of people will understand, but the challenge is to get as close to that as possible, and it’s extremely challenging. So, submitting my designs to more rigorous blind playtesting in the future is an obvious goal.

Grant: What is the status of one of your other ongoing games John Brown? Has it found a publisher as of yet?

Alex: My John Brown game is still in the works, but there’s no news to report. It’s still going to be a 2-part game, the first part about the northern abolitionist movement’s clandestine activities, and the second part a storytelling adventure delving into the actual raid on Harper’s Ferry.

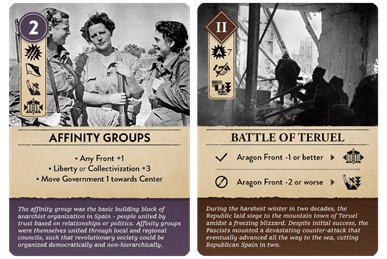

The next game of mine to be released will probably be the 2nd Edition of Land and Freedom, with massively upgraded art and components, as well as improved balance and gameplay. Here is a peek at a rough draft of some of the cards from the new edition:

Grant: What is your new game Hammer and Sickle about?

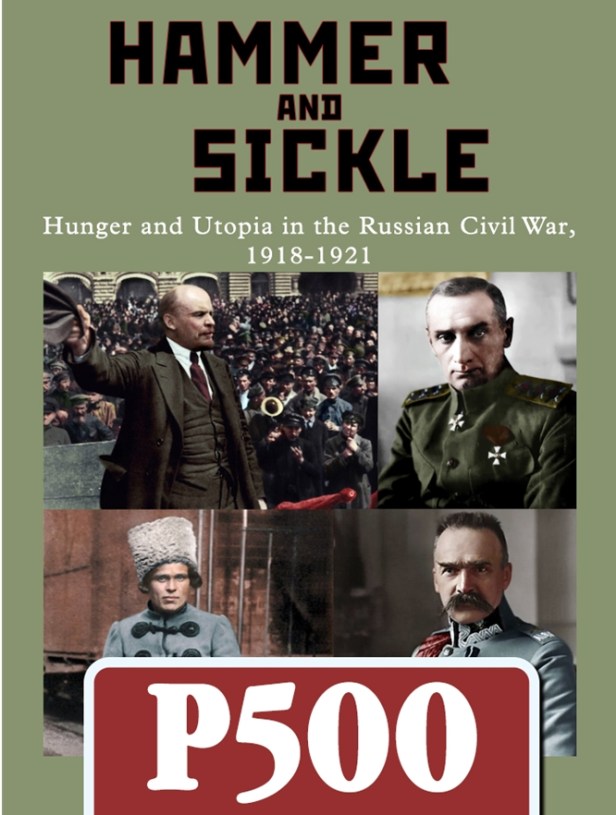

Alex: Hammer and Sickle is an asymmetrical game for 1-4 players covering the Russian Civil War from 1918-1921. The four factions are Anarchists, Bolsheviks, New Nations, and Whites, each with their own objectives, tokens, and abilities. The focus is a streamlined, easy-to-learn ruleset that facilitates lots of player interaction in a game that takes about 2-3 hours. I’m really excited that GMT is publishing it and that we’ve met the P500 goal. Plus I get to work with developer Joe Dewhurst, which is a real honor and pleasure.

Grant: What does the subtitle “Hunger and Utopia in the Russian Civil War” mean and what should it portray to players about the game?

Alex: Hunger refers to the scarcity that permeates every aspect of gameplay, as well as the history. The Civil War coincided with a massive famine in Russia that brought down millions of people. In the game, there’s not just a scarcity of Food, the most elemental resource in the game’s economy, but also a scarcity of Actions, Commanders (essential for Combat), Firepower (the other key resource), and Objective Cards (one of the main ways to score Victory Points). The restrictive nature of this ever-present scarcity forces players to behave strategically, and the player that forges the best strategy given these restrictions is usually the winner of the game.

Utopia refers to the high hopes that each of the four factions held at the beginning of the game’s timeline of November 1918. With the end of World War I and the collapse of the old Tsarist Empire, each faction surged to fill the consequent power vacuum with their own particular philosophy for how the new world should look. And as the space was quickly slammed shut, their utopias smashed into shards of bitterness. What this says to players is that Hammer and Sickle begins as a canvas for the best intentions, but opportunities not seized will haunt you long after the game is over.

Grant: Why was this a subject that drew your interest?

Alex: The Russian Revolution and Civil War was probably the defining period of 20th Century politics, setting up the enduring conflict between three poles of Communism, Fascism, and Western “liberal” Imperialism. For that reason, the subject draws the interest of anyone interested in 20th Century history or politics.

Personally, my investment in the period came through reading Emma Goldman’s memoir My Disillusionment in Russia, in which America’s most famous anarchist recounts her journey from being exiled by the U.S. for anti-war activity, to optimistically volunteering to work with Lenin’s new regime to spread the workers’ revolution in her native land, to being thoroughly disgusted at the systematic repression of that revolution by the very same Bolshevik State, and ultimately having to flee Russia forever. That narrative resonated with my own journey at the time (2007) while living in Venezuela. As a young anti-war activist who was disappointed by the lack of democracy or true transformation in the “socialist” regime I was witnessing in South America, Goldman’s account pointed me not only toward Russia and the past, but toward deeper, more meaningful political change in the future.

Grant: What is your design goal with the game?

Alex: The thesis of the game is to show how the Russian Civil War was much more than simply Reds vs. Whites. It was also a conflict between various nationalities demanding independence from an Empire, and above all a conflict between rebellious working class populations and competing projects of state-formation attempting to either suppress or co-opt that rebelliousness in order to gain supremacy.

The goal of the design is to streamline those complexities into a four-faction tabletop joy-machine, which plays quickly while maximizing player interaction and strategic decision-making, all in a very accessible ruleset. I think I’ve achieved this by allowing the asymmetries of the factions to orbit around basic rules like: one turn = play one card to activate one territory, and emphasizing the right kind of uncertainty when it comes to Combat, such that a large troop advantage doesn’t guarantee victory, not because of bad luck, but because of misreading your opponent(s). The possibility exists for unexpected support from other forces or an enemy going all-out with the bid of a fistful of firepower. In other words, players generally win or lose because of negotiation, smart bidding, and risk management, not because they didn’t understand an arcane rulebook or because of bad dice rolls.

This follows my general design philosophy of trying to make the most widely accessible and addictively-fun game that could theoretically inspire players to want to learn more about historical events that challenge mainstream assumptions about the past and present.

Grant: What sources did you consult about the details of the history? What one must read source would you recommend?

Alex: There are many valuable sources to consult about the Russian Revolution and Civil War – far too many to list. If podcasts are your thing, check out the (extremely detailed) Revolutions podcast series that Mike Duncan did with an entire series on Russia. If you prefer video, The Great War YouTube channel did quite a lot of excellent videos from 2017-2021 in a chronological 100-years-later approach that covered many tumultuous events in the former Russian Empire.

In book form, along with the aforementioned Emma Goldman memoir, you can get quite a lot from other radical contemporary accounts, such as Voline’s The Unknown Revolution, which gives detailed first-hand and second-hand accounts on such events as the Makhnovist insurgency and the rebellion of the Kronstadt sailors.

Yet, the best starting point for a big-picture view of the conflict as a whole is Jonathan Smele’s The ‘Russian’ Civil Wars 1916-1926, because it emphasizes the full scope of events beyond simply Red vs. White, including nationalist movements and peasant rebellions, in a surprisingly concise volume.

Grant: What other games did you draw inspiration from?

Alex: Strangely enough, the very first prototype was partially inspired by the Game of Thrones Board Game, though I quickly abandoned the idea of secret pre-programmed actions found in that title. My game also was inspired by elements of Tammany Hall, particularly the blind bidding in Combat, and the way turn order is determined via the Events drew indirect inspiration from Viticulture. This all goes back to 2019 when I began working on Hammer and Sickle.

Grant: What has been your most challenging design obstacle to overcome with the game? How did you solve the problem?

Alex: The most persistent problem until recently was how to prevent players who were falling behind from essentially giving up and throwing their support behind their supposed “ally.” The solution came not in the form of a catch-up logic, but through a mechanism called Season Goals. Season Goals are a public objective that all players compete over, for example “Most Combats Won.” Each Season has a different Goal, and at the end of the Season, whoever performed the best in that particular Goal receives Victory Points equal to the number of the Season. Since the game runs a maximum of 6 Seasons, the value of the Season Goals increases in a linear fashion as the game progresses. Therefore, if a player is falling behind, they always have an opportunity to seize a huge chunk of VP’s later in the game by focusing on Season Goals.

The introduction of Season Goals also solved some problems with the fact that all scoring used to come only from secret Objectives, which I will discuss in response to a later question.

Grant: You already mentioned this above but what are the 4 different factions in the game? How does each faction differ from each other?

Alex: The four factions are: Anarchists, Bolsheviks, New Nations, and White Army.

The Anarchists represent all left-wing opposition to the Bolshevik (Soviet) regime, especially through Makhno’s Black Army, the Kronstadt sailors, and peasant uprisings (Green Armies). Their asymmetry in the game is Agitation, a unique token they can build up in enemy territories to shut down production and even cause rebellions, which effectively turn territories Anarchist without requiring Combat. The Anarchists have few troops and little Firepower, but can spread rapidly through Agitation.

The Bolsheviks, led by Lenin, have control of the urban industrial centers of the former Russian Empire, and therefore can theoretically produce a large quantity of troops and Firepower, however without a large agricultural base they risk starvation and therefore economic collapse. The unique token of the Bolsheviks is the Armored Train, representing Trotsky’s famous armored train, which unlike Firepower is a renewable weapon that can be used in Combat once per Season. Further, the Armored Train can be upgraded to become increasingly powerful over the long term.

The New Nations encompass all the territories of the former Russian Empire that declared independence and tried to break away after the end of World War I, from Finland to the Baltic states, to Poland and Ukraine, all the way down to the Caucasus. The New Nations’ asymmetries include their control of the seas, allowing movement between coastal territories, due to the backing of the British Navy, along with the unique token of Nationalism, which provides bonuses both in Combat as well as in recruiting new troops.

The White Army, finally, represent the counter-revolutionary forces of Kolchak, Denikin, et al. The Whites’ asymmetries include their receipt of superior amounts of Foreign Aid from Imperial Russia’s erstwhile Western allies, in the form of Food and Firepower, which can be upgraded to higher quantities later in the game. The Whites’ unique token is Terror, representing their systematic anti-Semitic pogroms and counter-revolutionary violence. Terror is a currency the White faction uses for benefits including improved recruitment and wiping out Agitation.

Grant: What is the overall goal of each player?

Alex: There are two loose alliances in the game, a Revolutionary Alliance of Anarchists and Bolsheviks, and a Counter-Revolutionary Alliance of New Nations and Whites. Unlike Land and Freedom, it is a totally competitive game, so one and only one faction will win. But there is an incentive to work with one’s “ally” to the extent that the target score for winning the game is based on the total number of territories held by your Alliance. The two Alliances are therefore in a tug of war to pull the victory star closer toward their side.

Ultimately, though, each player is working for their own victory, and it is entirely likely that you will have to betray your “ally” if they control a territory that you require for an Objective, or simply to deny them from snatching victory away from you. You want to score as many Victory Points as possible, hold your “ally” in check to minimize their VP, all while working together to weaken the enemy alliance overall.

Each faction has its own secret Objectives, 3 “Heroic” Objectives which are quite difficult and 3 regular Objectives. These are particular to the different factions and reflect historical goals. For example, the White Army faction has designs on Moscow and Petrograd, while the New Nations’ Objectives are primarily about defending and strengthening their own territories.

Grant: How does negotiation factor into the design?

Alex: Tabletop board games, as distinct to video games, are an inherently social experience. There’s not much better than sitting face-to-face with friends or acquaintances and interacting with the same puzzle from different angles. For me, negotiation is one of the great joys of board games. How can what I have be useful to you, and can what you have be even more useful to me? So I definitely lean toward incorporating negotiation into my designs.

In Hammer and Sickle, players can trade resources – primarily Food and Firepower. They can also ask for and promise Support in Combat, and they can even negotiate which faction’s troops will take casualties in battle. Agreements are not binding, so betrayal is always an option as well. But if you burn your ally, don’t expect them to come save you when Moscow is attacked.

Grant: How does the game use cards? What different type of cards are included?

Alex: You could call Hammer and Sickle a Card-Driven Game in the literal sense that cards drive the action, but it’s not a typical CDG in terms of mechanics. There are three main types of cards in the design: Objectives, Events, and Actions/Commanders, as seen below.

Grant: Can you show us a few examples of cards and tell us how they are used?

Alex: Here is an example of an Objective Card. It is a Bolshevik Objective called Seize the Oil Fields of Baku!, worth 4 VP if completed. The “normal” Objectives range from 1 to 5 VP, while the “Heroic” Objectives range from 6 to 9 VP and are more difficult. Also, on the top-right of the card is a Firepower symbol, which is the bonus acquired by the player if they discard the Objective, either abandoning it before completion, or discarding it after completion to gain the Firepower. There’s a set collection element – each faction has 3 suits of bonuses, and if a player completes a set of each of the 3 bonuses, they earn a bonus 3 VP as well.

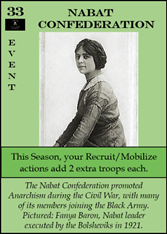

Here is an Anarchist Event Card called Nabat Confederation. On the top-left is found the Morale Number, ranging from a low of 1 to a high of 100. Players bid their Event each Season, with the highest Morale assigning the first player that Season and the lowest Morale designating the last player to act. Since Morale is also the tie-break in Combat, it’s generally beneficial to have higher Morale. But of course, the Events with a higher Morale number are proportionally weaker in immediate effect.

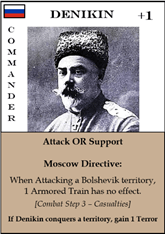

Finally here is a White Commander Card. Each faction has 7 Action/Commander Cards, which stay in their hand throughout the game and can each be played once per Season. Commander Cards are used to initiate Combat, or to Support a Combat on another player’s turn. They are played face-down until Combat is resolved, and each player has a Bluff Card as well which feigns involvement in Combat to confuse the enemy. The other Action Cards are played face-up on your turn and include both a free Basic Action as well as an “Advanced” Action, which has a cost.

Grant: How is the economy of the Russian Revolution represented?

Alex: There are two types of Productive Territories: Hammer Territories and Sickle Territories, and they produce the two basic resources of the game – Firepower and Food.

Sickles represent the agricultural workers (or peasants), and they produce Food. In the Summer Seasons, each Sickle produces 1 Food. In the Winter, two Sickles are required to produce 1 Food.

Hammers represent the industrial workers, and they produce Firepower, but only on the condition that they receive Food. For each of your Hammers that you feed, regardless of Season, you receive 1 Firepower. But, each Hammer you don’t feed instead produces Agitation, which threatens a possible Anarchist rebellion.

Because of the need to balance these two symbols, along with the prevalence of Winter, there is always an inherent scarcity to the economy, as players with a lack of Hammers struggle to produce enough Firepower to defend themselves, and players with a lack of Sickles struggle to avoid being overrun with Agitation.

Grant: How does combat play out in the design?

Alex: The player initiating an Attack plays a Commander Card face-down and moves their troops into the (adjacent) territory they are attacking. This then prompts all adjacent players to decide whether they want to Support either the Attacker or the Defender. If they so choose, they play one of their own Commanders face-down and bring their troops into the Combat territory. But, they could be Bluffing (see next question).

The cost of Supporting is the loss of your Commander for the remainder of this Season AND the next Season, since effectively you’re playing a card out of turn. The benefit is that you can potentially swing the combat with your troops, Commander abilities, and Firepower.

Once all Support has been declared, players with troops in the combat bid their Firepower (and the Bolshevik player can bid their Armored Train). Each firepower removes 1 enemy troop from the board. Then Commander abilities are triggered if relevant, and finally the side with greater remaining Strength wins the combat. The losing side must retreat if possible – if the Defender loses and has no adjacent territory to retreat to, their troops are removed.

In this example, the Bolshevik player has 3 troops and their Claim in Kyiv (+1) for a total Strength of 4. The New Nations player has 2 troops (1 supporting), plus 1 Nationalism (+2), and Pilsudski has a +1 bonus for a total Strength of 5. The Bolshevik troops must retreat.

Grant: How does each side use bluffing, bidding and negotiation in combat?

Alex: I find it much more thrilling to attempt to calculate how much of my resources to risk on a move, while attempting to read my opponent(s) and whether they’re bluffing, rather than letting a roll of the dice determine my fate. So this is how the Combat system is designed in Hammer and Sickle. On top of that, players can negotiate all throughout the game, exchanging resources for immediate advantages or vague promises. For example, in Combat the Attacker and Defender are the ones responsible for assigning casualties to the troops on their side of the combat. So, if Player A decides to support Player B in their defense, one condition they could demand for this support could be to not take any casualties. It would then be up to Player B to decide whether to honor this request, or burn that bridge.

Grant: What type of an experience does this process create?

Alex: In my experience, Hammer and Sickle is my most fun game, because you need to understand what your enemies are doing and how to best them, and if you lose a crucial battle there is usually a lesson to be learned. Maybe you simply didn’t devote enough resources, or maybe that battle was always going to be a loss and it would have been better to sacrifice it without wasting any resources on it at all.

Even a victory can often come with lessons learned, if you’ve overcommitted resources to ensure something that could have been won easily enough through a simple bluff. These are the errors that live with you long after a game is concluded, and make you want to play again, I hope.

Grant: How much of a role does short-term and long-term planning play in the design?

Alex: The Heroic Objectives give players something long-term to work toward over the course of the game. It might take the entire game to fulfill one, particularly while much of your attention goes to more limited objectives or to the short-term fires that have a tendency to break out constantly. Also, with the Season Goals as explained above, there is always a new way to score VP’s should you choose to focus on that competition in each particular season. I think there is a good mix of short-term and long-term strategy required for a winning player.

Grant: How is victory achieved?

Alex: As mentioned above, the target score for winning the game is according to the total number of territories held by each Alliance (Revolutionary and Counter-Revolutionary). As territories change hands, the target score therefore is pulled back and forth on either side of the middle of the victory track. Meanwhile, each player scores VP based on their objectives and the Season Goals, inching their VP token up the track toward that target score. As soon as one player’s VP marker reaches the target score, they win the game.

There are a maximum of six Seasons in the game, ending with Summer 1921. If no player has achieved victory at that point, the player whose VP marker is closest to the target score is the winner. However, most games in my experience will end before the conclusion of Season 6 with an immediate victory.

Grant: What are you most pleased with about the design?

Alex: Even though I’ve been working on the game for the last six years, the current game isn’t radically different from the game that existed near the beginning. It has been distilled and refined continuously, but the core experience is largely intact. There hasn’t been a great deal of rules that have needed to be added, and the additions that have been brought in, particularly some of the asymmetries (Armored Trains, Nationalism, Terror), fit right into the game flow and enrich the overall experience with very little added complexity.

Grant: What has been the experience of your playtesters?

Alex: Very positive, I’ve found. I have learned a great deal from them, and I owe them tremendously. A game designer is lost without excellent and critical playtesters, and I’ve been very lucky so far in that regard.

Grant: What other designs are you mulling over?

Alex: I’ve started researching and brainstorming for a possible game on the French Revolution, specifically the heroic period (1789-1792). But it’s too early to say anything more!

If you are interested in Hammer and Sickle: Hunger and Utopia in the Russian Civil War, 1918-1921, you can pre-order a copy for $62.00 on the P500 game page at the following link: https://www.gmtgames.com/p-1081-hammer-and-sickle.asp

-Grant

I don’t believe the game’s author is ignorant of the history of the Russian Civil War and doesn’t realize that the Red Terror was an order of magnitude larger than the White Terror. It was the Reds who officially issued the decree “On the Red Terror,” while the Whites had no such law. The White Terror was more spontaneous, though certainly no less brutal.

It’s a shame that the author’s political views force him to go against the truth, ignore historical facts, and gloss over the crimes of the Bolsheviks.

LikeLike