Last year, I came upon the In Development section of the VUCA Simulations website and saw a very interesting looking operational level wargame on the German invasion of Poland in 1939 to kickoff World War II called In Fours to Heaven. The subject caught my eye, the title caught my eye and the cover caught my eye and I reached out to the designer Grzegorz Kuryłowicz to see if he was willing to share on the design.

Grant: Gregorz welcome to our blog. First off please tell us a little about yourself. What are your hobbies? What’s your day job?

Gregorz: I’m from Gdańsk, Poland. My day job is driving long run passenger trains in Poland. My hobbies besides wargaming are (of course) history. I used to be a reenactor of Rangers Battalion with my personal M1. I’m a musician on guitar and piano, used to play Hammond organ in a few bands and did some recordings with them. I also enjoy classic cars and own a registered vintage Fiat 125p. I also have two little kids, so time is my lethal enemy at the moment.

Grant: What motivated you to break into game design? What have you enjoyed most about the experience thus far?

Gregorz: I used to design many small games for fun for years. The In Fours to Heaven project was also created just for personal use, to fill the gap of operational games about Poland 1939 that will fit my taste. I started experimenting with a lot of unusual mechanics. At some point it started to gain solid shape which I was encouraged to present to a publisher. When I first saw Nach Paris by VUCA Simulations, I right away saw my dream game in this shape. I contacted Patrick and it turned out to be a great decision, as he got interested in the project. And here we are. I most enjoyed a kind of scientific approach, when you have an idea, test it and it turns out to work beyond expectations. Especially when it turns out to fit historical results.

Grant: What lessons have you learned from designing your first game?

Gregorz: The most important lesson is to lower expectations about being sure that the game is complete. It is a never ending story to complete every mechanic and finish the rulebook. In each step of serious game design I learn on every step what to do or not to do while trying to pour your innovations into the game. The “designer’s bias” is your worst enemy. The key to success is to ask yourself a series of questions about every paragraph – “what purpose is this rule for in the game?”, or “does this rule really change anything?”.

Grant: What is your new upcoming game In Fours to Heaven about?

Gregorz: It is an operational/strategic level game about the whole Poland 1939 campaign. At first look it is a bit one-sided campaign, but once you start digging in, it is very dynamic and not really easy for the German side. The key to make it a two-player game, interesting for both players, is to focus on the victory conditions approach. The good comparison is the Battle of the Bulge. If you focus on the strategic goal – Antwerp, a game is certainly always lost by the German side. Similarly, if in Poland ’39 you want to fight for the absolute victory, the Polish side stands no chance. If you focus on operational goals, we have a different beast. Not everyone is aware that Poles launched two large scale counteroffensives that achieved local success during the course of the campaign.

Grant: What is the meaning for the title? What should it convey to the players?

Gregorz: The title is a long story and it has multiple meanings. First, in loose translation it is a line of a poem about Westerplatte defenders (the famous military depot defense in Gdańsk, at the beginning of the campaign). This poem is taught in schools, thus everyone knows it. It is one of the Polish symbols of World War II and a very important one for this campaign. Secondly, the mechanics of the game focus heavily on the morale of the Polish side which represents many factors. As Westerplatte defense was broadcast during the campaign it gave a kind of hope and fighting spirit at the time. As those symbols are an important part of the game, the title itself gives you a clue, what is this game about beyond hexes and counters. And last but not least, I always like unusual titles. They always catch your attention and make you want to explore a story behind such a title. I believe, the title itself with its multi-layer significance, is something that will make any gamer stop for a second and take a look, what this game is about.

Grant: Why was this a subject you wanted to focus on?

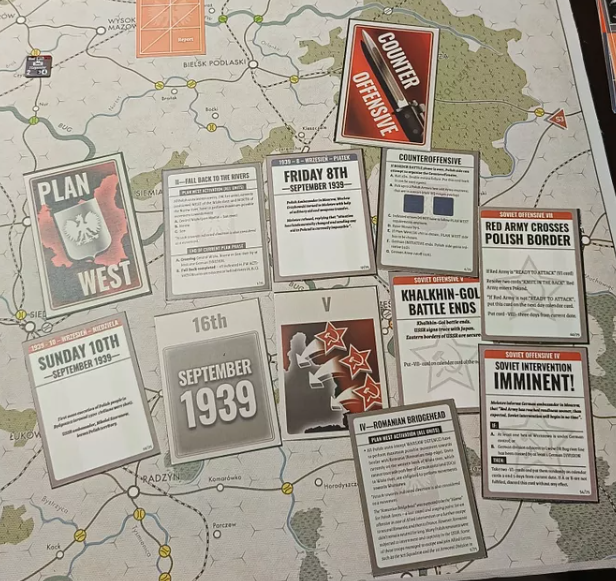

Gregorz: I wanted to focus on the deep reasons behind the Polish disastrous defeat. Those do not lay in strength balance, numbers of tanks or simple maneuvers on the map. I believe, that no game about this campaign can show the history accurately if some aspects of it are left behind. And one of these aspects, which is a major part of this game is the Polish defensive plan, the Plan West. The game shows and explains, how it was planned, implemented and finally how it caused the initial catastrophe in the “Border Battle” stage. But also I wanted to avoid a scripted scenario of the campaign. And here is where the Morale mechanics come into play. The Morale is kind of a resource for the Polish player to “burn” to deviate from the defensive plan. It is influenced heavily by both sides. In a way, both players have absolute freedom of actions with some historically justified risks if any player decides to break off historical paths.

Grant: What is your design goal with the game?

Gregorz: The main design goal is to present this campaign in a different context – using the aforementioned Morale and Plan West mechanics. I want players interested to play this game to be encouraged to know more about the campaign and the history behind it.

Grant: What is the scale of the game? Force structure of the units?

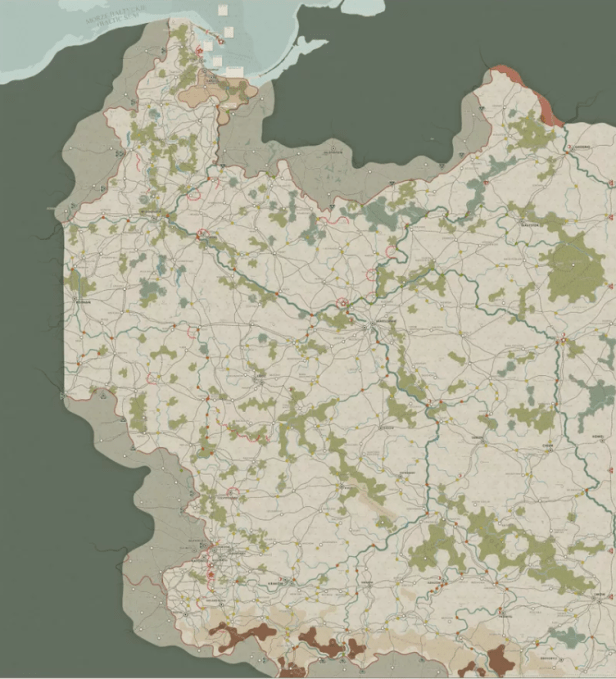

Gregorz: Units scale is division/brigade with options to make regiment detachments. The map represents around 70% of Polish territory in 1939 (the eastern area is not used) where one hex represents around 10 kilometers of real terrain.

Grant: What is the anatomy of the counters?

Gregorz: The counters are mostly standard for a hex and counter wargame. Combat units contain combat strength, movement allowance, formation subordination, HQ’s contain different types of HQ range. But the game uses many innovative mechanics. For example, in any combat, if more than one unit attacks (even from one hex), the attack needs a coordination check. A lot of new concepts will demand some learning but to flatten the learning curve, the players will find five small learning scenarios which are designed in a way that rules are introduced in stages.

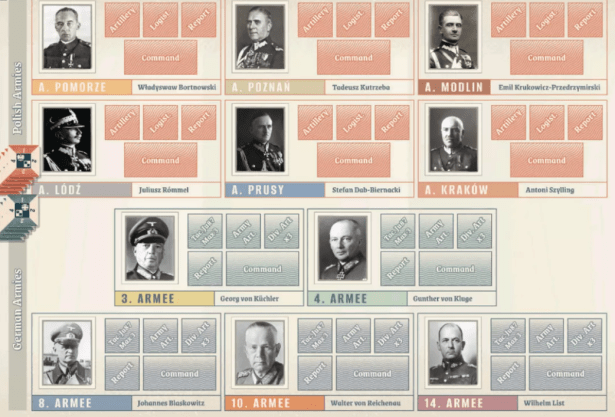

Grant: What different type of units are included on each side?

Gregorz: Basically units are the same for both sides and have the same strengths, except German Panzer divisions. It represents real manpower in units, which wasn’t very different. The German advantage in firepower is literally represented by artillery assets, where the German advantage is approximately calculated to be 4-1/3-1 with addition of almost complete air supremacy. The compositions of armies are a bit different.

Grant: What special units are included on both sides?

Gregorz: The German side mostly have special units which include Leichte divisions (which can detach one infantry regiment), mountain infantry and SS regiments (which count differently for the City Clearing and have more freedom of movement between armies). The Polish side on the other hand have a large cavalry advantage, which also have some special rules.

Grant: How have you modeled the terrible force of the German Blitzkrieg?

Gregorz: The German Blitzkrieg actually wasn’t as effective as in 1940 and 1941. The German Panzer spearheads faced serious supply issues and rarely cooperated with the Luftwaffe. Mistakes learned in Poland were a significant factor for the 1940 France campaign. But of course, the difference between sides is modeled. The most important aspect is the overall larger command range of German HQ’s, which allow deeper strikes. Secondly, the German Motorized Corps have special activation chits which allow them to perform more actions.

Grant: How do the Polish units withstand the attack and what strategies are important for them to follow?

Gregorz: It is a matter of deeper gameplay analysis. The most important aspect of the Polish defensive war is to keep the balance between the Morale and following the defensive Plan West assumptions. Moreover, the Polish player has an option to start the counteroffensive which has a series of effects on Morale and organizational aspects. Basically, armies are limited by the Area of Operations. It means that units of different armies cannot attack together and cannot move in one another’s areas. The Counteroffensive cancels this limit for two armies that are designated for the offensive.

Grant: What is the layout of the board look like and what areas of Poland are included?

Gregorz: The map includes around 70% of 1939 Poland’s territory. The leftover is the eastern area, not used in the main event as well as part of Poznań area which has not been used by the German side for the attack of field armies. The Soviet attack is included in the game but in other ways. Instead of using units, the Soviet fronts work as a mobile map boundary. In any case, the area of the map allows players to fight the whole historical campaign.

Grant: What strategic pinch points are created by the terrain?

Gregorz: The terrain influences the game on many levels. The most important level is strategic, where large rivers are major obstacles. In many descriptions of the campaign, information can be found about low water levels as an effect of the dry summer. In detailed books and thick unit monographies it is always clear that any water barrier is a serious obstacle. This is why rivers are presented as the most important defensive lines. Additionally, major rivers play the key part in the Plan West. The other level is tactical. In this game, rear areas of any units are significant. The Combat Results Table generates a few types of retreats after a combat. Depending on the result it could be an organized withdrawal or panic retreat. In the first case, the defensive terrain will provide cover and can shorten the retreat rate. In the second case, the rough terrain causes cohesion issues, scattering the retreating units, causing additional step losses. On top of that, usage of German Ju87 dive bombers can further damage defenders in open terrain or on a road. In a nutshell, terrain effects in this game have a huge importance. Regarding low counter density on the map, I wanted to elevate the importance of the situation rather than fake seeking for gamey “this just one more factor”.

Grant: What are the German objectives on the board?

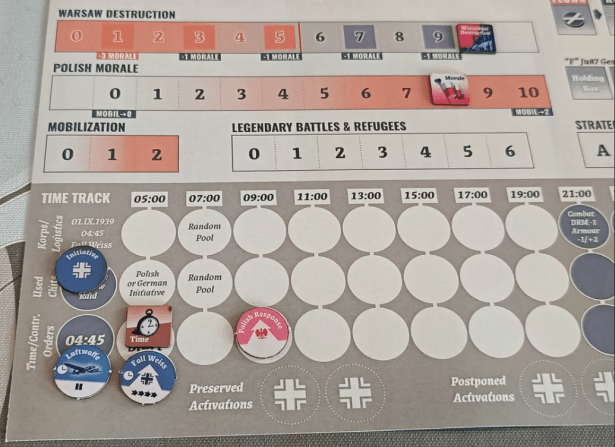

Gregorz: The scenarios and the campaign have vastly different victory objectives. On the operational level, victory conditions are based on map VP hexes and VP count. In the campaign, both sides have many ways to win (or lose from another point of view) which are not solid map goals. As an example, the Polish player loses immediately if the Morale in a certain part of the turn is at “0”. To keep the Morale level high, the Polish player needs to execute the Plan West, avoid being encircled and isolated, and finally, counterattack. So it is a very open world as fulfilling those demands is not fixed in certain map spots. To lower Morale, the German player needs to encircle Polish armies, control and clear Polish cities and bombard Warsaw. But there are alternatives, more solid goals, like cutting off the Polish General Staff escape road or controlling Warsaw hexes at the moment of Soviet entry, which is variable. It is not all, but just with these examples it gives an impression that there is a lot do and the whole map is a chess board for both players.

Grant: How does combat work in the design?

Gregorz: The combat is a mix of classic strength ratio CRT and new concepts. Any wargamer will immediately recognize one strange aspect of this game. Very low combat values. It is intentional as I want to focus more on real influence of unit numbers and position rather than of seeking for tiny combat factors just to score one more column shift. When the combat occurs, the key part will be played by DRMs from various factors like terrain, time of the day, unit types, size difference and support. CRT is not symmetrical. Results in ratio 3-1 or higher are much safer for the attacker. Speaking of which, I’ve added one additional line in the CRT – “<1 +1AL”. Only the large artillery support can provide column shifts. So if the terrain and support provide DRM’s, the combat result is limited by the ratio column. If you gather 2-1 force in an attack, no matter the conditions, it will be always the 2-1. Various conditions will only influence your die roll. If the attack is organized poorly – with lack of support, in hard terrain and possibly other negative factors, creating for example -5DRM, even if strength ratio is 6-1, the attacker will suffer a step loss. The +AL result means that if a die roll result is lower than “1”, the attacker suffers a step loss. This mechanic is countered by another new mechanic – Daily Report. All daily losses are recorded in every army. At the end of the day (turn) if losses were high, there is a chance to receive extra Replacement Points due to reorganisation of fatigued units. The last thing I want to point out here is the Combat Roll. A player always roll 2d6, but it is not a classic “2d6” roll. The CRT spreads from “1” to “8”. So it is basically a 1d6 table. But I’ve added some control of probability in a way, that in this 1d6 roll, the most probable results are “3” and “4”. In a nutshell, one die is designated the “primary” die. If any of the two dice contains “3” or “4”, it is the final result. If both dice have those results, or none, the “primary” gives the final result. This way players have much more control over combat and are able to influence it with great care. Moreover the combat system uses a few more uncommon mechanics, like coordination in multi-unit attacks, attack planning for the infantry and two types of Advance After Combat. In this case, it shows a major difference between foot and mobile units. After the combat if the defenders hex is vacant, in case of infantry, the Attack marker is advanced first. The attacking unit do not move until all attacks are executed. Contrary, a mobile unit will advance right away, just like in almost every other hex wargame. The idea here is, that a mobile unit can change ZOC situation after one combat and heavily influence retreat options for the defender, while a long line of infantry do not do this. This elevates the use of Panzer units in attempts to encirle enemy and very well models “Blitzkrieg” combat style, where the most deep strike work is really done by mobile force, not the infantry.

Grant: How have you modeled command and control? What is the concept of conflicting orders?

Gregorz: The command and control in the game is the most important tool to model difference between Polish and German style and capabilities of control over the battlefield. The HQ’s have command ranges, which are much higher in case of German than Polish. Being out of command range still allows a unit to activate but it has lower MP allowance and some limits regarding combat. Formations are activated by Activation Chits, which can be picked randomly from the cup or used “from hand” if are properly prepared earlier. Here we come to the most complex but innovative part of the game, which I am very proud of. Activation Chits come in various types, influencing different levels of the campaign. If anyone played the Grand Tactical Series from Multi-Man Publishing and is familiar with the concepts of “Division/Formation Activations”, will see it right away. The “Plan” chits activate all units on the map, but limit actions to one type per army (move or attack) and generate CO 4 (Conflicting Orders – I’ll get to this in a moment). The name “Plan” comes from the idea, that the highest staff issues orders according to their pre-war planning. Lower lever, Army chits activate units of one or two armies but give them freedom of action and generate CO 3. Then there are two additional levels – Motorized Corps and Commander Intervention (hello Direct Command chit), which activate only a few units, but give them more freedom and do not generate CO at all.

Conflicting Orders is a narrative mechanic that gives a feel of fluent and simultaneous events on the map. In many wargames, the gameplay could feel a little “episodic”. One player attacks. Then the other player responds, next turn. What the Conflicting Orders mechanic achieve is to create consequence of action. If you issue orders to one of your armies, its units will be busy executing them in the upcoming hours. If you issue another – “Conflicting” – orders too soon, the loss of cohesion and confusion is imminent. In the game it works like this – once you play a chit, you move it ahead the current Time marker with the CO value. Until the Time marker reaches such a chit, units activated by it suffer negative DRMs in combat and their parent HQ loses its Command Range. With this idea, it was a really easy way to properly model differences between sides in this conflict. Command feels much easier for the German player.

Grant: How are units activated?

Gregorz: Units are activated by Activation Chits. The number of units activated depends upon the chit level. Activation Chits can come randomly from the cup or be used “from hand” if are properly prepared. Both players have partial control over the course of actions, of course, German player much larger. Primarily, the first Activation of the turn is picked by the Initiative player. The initiative is fixed on the German side at the beginning of the campaign until the Polish player starts the Counteroffensive. Then for a limited period of time, the Polish player has the Initiative. After this, no player has it, thus the first chit of the Turn is always random. Secondly, both players might have an option to “preserve” one or more chits before the Turn. And lastly, in certain conditions if the Polish player performs any attacks, the Polish Tactical Initiative can be gained in a form of a usable chit, to take more chits randomly from the cup and pick which to play. When units are activated, depending on the level of activation (Plan or lower), the player can perform movement or combat in case of infantry, or movement and combat in case of mobile units. During the movement process, every unit have same additional options to utilize like detaching a regiment or loading to a Transport Train. In the question about the combat design I mentioned difference between foot and mobile units in Advance After Combat. But the difference between these two types is much deeper.

All foot units are limited by the DFR – Daily Foot Range. It means, that a foot unit can physically travel only limited number of hexes during the whole Turn. The move rate is a real one – 30/40 kilometers (3/4 hexes). Mobile units have no such limit. This mechanic gives a great opportunity to plan the whole day, when to move infantry. Moreover, counterattacks against infantry gain very high importance – retreating infantry “burns” its DFR limit, which could stall its planned actions for the reminder of the day.

Grant: How are cards used in the design?

Gregorz: The cards in the game come in a few genres. Only one card (Polish Counteroffensive) is actually an action card. The rest serves various purposes. The Plan West cards are the reference for actions to perform if the Plan West chit is played and contain conditions for the Plan advance. The General Staff cards mostly serve as a handy reference when and where will the Polish General Staff escape next. The three decks – Calendar, Allies, Soviets form a kind of additional Turn Track, which contains historical events and govern the Soviet entry. Calendar deck goes along with the Turn Track. The actions on Allies and Soviets card dictate, where to put the specific card to push the story forward. Some of Soviets cards contain also a conditions for the German player to achieve if Soviets are to attack. The single Polish Counteroffensive card is kind of an action card that contains conditions to start the Counteroffensive as well as actions to execute when it is announced. Lastly, the Soviet Front cards work as a group of units on the map instead of counters. Those are placed just like units, progress towards the West according to the schedule and simply close up the map for the Polish player.

Grant: What different scenarios are included?

Gregorz: The game will include 18 scenarios. Five of which are learning scenarios, other five are campaign scenarios (simply with different start dates) and the rest are operational battle scenarios, focusing on the smaller picture. Average game time for battle scenarios is 4-8 hours, The full campaign takes around 100-120 hours to complete (of course it can end much earlier with a Sudden Death victory). The first learning scenario takes around 15-20 minutes to play with just 5 units on the map. The learning scenarios are designed in a way, that they use the main rules but in parts. The game will include additinal book – “Learning Rulebook” which will have the same composition as the main rulebook, but all unneeded paragraphs will be cut or highlighted not to be used. Besides, there is a very interestind procedure for anyone who do not know much about the campaign. The first learning scenario – the Battle of Kock – is actually the last battle of the campaign. The third scenario takes place in Gdańsk. The fourth with some more rules added, south of Gdańsk, on the Pomerania Corridor and the fifth with some more rules added (but still not the complete set), just east of the Corridor. The scenario “6” is a thrown in half-campaign scenario – HG Nord. The interesting fact is, that this scenario uses the full set of rules and combines scenarios 3, 4 and 5 into one large scenario. The player who lears the game knows already the OdB of every part of this front, terrain and will be able to discover, how those battles influenced each other. I put very strong pressure on lowering the learning curve as I’m very well aware, that releasing a very innovative, complex game about topic that is not very popular could be a diseaster. But with this learning process included in the game, entry level is much lowered.

Grant: What type of an experience does the game create?

Gregorz: The game creates mostly a narrative type of experience. Thanks to the Time Track, realistic flow of time, infantry DFR limits and shifting Morale of the Polish side you can feel the dynamics of the situation. The usage of Calendar, Allies and Soviets cards additionally creates a strategic layer of the story. In the Optional Rules, which contain some of older complex mechanics, that were simplified in the course of playtesting, two narrative-focused rules are included. Both need dedicated note-sheet, which will be posted on the VUCA site for print. The first is a table to note all Legendary Battle events, that occur during the game. Legendary Battles can be achieved by the Polish player to elevate Morale level by performing actions like Cavalry Raids. Every such successfull event can be noted with the exact place and hour (e.g. Mokra village – 13:00, Wil cav brig stops German 4Pz advance, suffering high losses). The second is influenced by tens of army monographs that I’ve read the design process. Warpaths. The sheet will include spaces to write down unit ID, possibly commanders name and tables for actions. You simply focus on one unit and write down series of actions, that unit performs during the campaign. After the scenario, or better – campaign it creates very strong experience, to track down, where the unit was and how hard was combat for it.

Grant: What are you most pleased about with the design?

Gregorz: I’m definitely most pleased with finding the right pattern to fit in historical boundaries and in the same time give players some justified freedom of action. In any campaign, or even war, circumstances for battles could be so vastly different, that I believe, there is no universal system, that can fit every battle without extra mechanics. The Poland 1939 campaign is an awful campaign to model in the wargame. The whole concept actually was born in the boiling pot of crazy ideas. Through the years (about 6 since the first full working prototype was done) it needed hundreds of hours of playtesting, adjustments to just partially fit the situation. At this moment, in the process of scenario designs, there was a breakthrough moment, where it all started to click. No matter, which battle I took, all units, HQ’s and many different aspects were there, working just like described in history books. I believe, I’ve modelled a system, that tells the story of this campaign properly. It is complex but also wargamers might find interesting to explore my point of view in many mechanics. In the rulebook, I’ve included a lot of Designers Notes to explain my design choices regarding almost every aspect of the game and historical background arround it.

Grant: What has been the response of playtesters?

Gregorz: My best playtesters, that are with the project from the beginning very much enjoy the game and provide me great feedback. With other playtesters it is always a hard start to get into the new system with such amount of new mechanics. But it is already proven, that learning process works fine. The best word to describe the response is “intriguing”. But I think, the game will be an interesting mystery to investigate for any grognard or at least experienced wargamer.

Grant: What other designs are you working on?

Gregorz: At the moment two designs are “in progress”. The first is the next game in the Formations Series by VUCA Simulations and it’s also about the Poland ‘39 – Tomaszów Lubelski battle. It is the second Polish offensive of the campaign and takes place at the end of the campaign. The game is almost ready and is already playtested by a few players via Vassal module. The second is a new design about medieval battles. Block wargame about Grunwald battle in 1410. The game uses card orders and was already playtested a few times at conventions. But I don’t have time right now to get it finished. There is also a folder with a tactical system in squad scale. In the future, I’d like to come out with the second game in the same (or similar) system as In Fours to Heaven, about Greece 1941 – mainland campaign and Crete. I’ve already started to work on the map and OoB. In the longer run, I’d like to continue designing games in this system. Amongst many ideas, there is Poland ’44-’45, France ’40 and maybe a little different, wider approach to the Market-Garden operation.

Besides wargames, I’m designing two games about trains in Poland, have a 15+ years old idea for a fantasy adventure game. And the last is my dream idea – to design a large, complex game (in scale of e.g. Twilight Imperium) about the prequel trilogy of Star Wars. Just like FFG’s Rebellion is about seeking hidden Rebel bases, I see a game about revealing Palpatine’s plot while fighting a complex war between the Clone Army and Separatists, with a layer of politics in the Galactic Senate. I have a full notebook of ideas, but it takes a horrendous amount of time and energy to kick such a game off and keep it running. Some day…maybe in retirement.

Thank you so much for your time in answering our questions Gregorz. I am very much interested in this game and cannot wait to see how it develops.

If you are interested in learning more about In Fours to Heaven: The Invasion of Poland 1939, you can check out the game page on the VUCA Simulations website (although this is more of a quick blurb on the front page) at the following link: https://vucasims.com/

-Grant