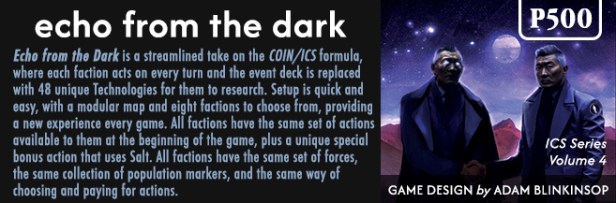

In case you didn’t know, the Irregular Conflicts Series is a spin-off from the COIN Series and attempts to adapt the core mechanics to model different kinds of historical (and now non-historical) irregular conflicts beyond counterinsurgencies. The previous 3 announced volumes include Vijayanagara, which is a look at Medieval India and a struggle between the Delhi Sultanate, Bahmani Kingdom and Vijayanagara Empire, A Gest of Robin Hood which is an asymmetric fight between the forces of the Sheriff of Nottingham and Robin Hood and his Merry Men and Cross Bronx Expressway, which looks at the philosophical battle that raged between stakeholders in the 1970’s when the interstate cut through the city of New York. All of these games are based in history/myth and now we have a new volume that is a sci-fi epic called Echo from the Dark designed by Adam Blinkinsop. We reached out to Adam to get some more information about the design and he was more than willing to answer our questions.

Grant: Welcome to the blog Adam. First off, please tell us a little about yourself. What are your hobbies? What’s your day job?

Adam: Hello! My name is Adam Blinkinsop, and I’ve been working in software for a while now.

My hobbies revolve around getting away from a screen: playing and making games, listening to and making music, and tasting wine. I’ve so far managed to avoid trying to make wine, but we’ll see how long that lasts.

Grant: What motivated you to break into game design? What have you enjoyed most about the experience thus far?

Adam: I like to make things! Tabletop games are a fun category of thing to make, and around 2010 I had a group of folks willing to play whatever got to the table. We did our own little game jams with the goal being to bring something playable to the table. The best way to gain experience is to fail a bunch, and we did that very well — the best way to get some humility in game design is to play a ton of your own prototypes.

I designed several of these using the Decktet, and P. D. Magnus (its creator) was especially welcoming when I threw them onto BGG and the Decktet wiki. Getting the chance to talk to the design community here and in role-playing games has always filled my battery. However, I probably most enjoy seeing folks playing these games! Hosting demos at conventions or sharing print-and-play games with excited folks online is such a fun experience.

Grant: What lessons have you learned from designing your first game?

Adam: I’ve had a long slow ramp up to publishing Echo from the Dark, which has included a bunch of smaller, print-and-play design work, development work on my friends’ games, and development work for GMT Games, so it’s tricky to narrow it down for sure.

One major lesson over the past decade or so is that what one group finds enjoyable, another group will find annoying. It’s important to have some sort of anchor on the experience so the design doesn’t oscillate around the various playtest groups — something I continue to have a difficult time with, as it’s so easy to focus on moment-to-moment feedback. Perhaps I’m still learning this lesson.

Another: there’s no replacement for actual play during the design and development process. Other designers are probably better at this than myself, but I find that a playtest always reveals something unexpected about the systems I build. It doesn’t seem to matter how simple the game is or how often I’ve played it before, new players reveal new aspects to play.

Finally, allow people to help, and play to your helpers’ strengths. A great thing about working with GMT is that there are so many people willing to help out with a new game. I have practically a team of folks willing to help brainstorm ideas for solving a systematic problem, work on graphic design and proofreading, dig into manufacturing requirements and constraints, let alone a great artist I can trust to augment my technology and sector briefs. Trying to do this stuff on my own would be difficult to impossible, even before getting to the manufacturing part of the process. With all the support, I can focus on the parts I do well.

Grant: What is your new upcoming game Echo from the Dark about?

Adam: Echo from the Dark is about history and science fiction. I’ve been reading sci-fi my entire life, but historical wargaming is relatively recent for me. After COIN, the idea of playing a big 4X game where all the players were imperial powers started to feel really weird. Where are the insurgents in Twilight Imperium? Where is the unrest in Eclipse?

Simultaneously, I’ve had a design percolating about the rise and fall of empires since before Andean Abyss came out. Players dug through a deck of technology and bid to preserve provinces from collapsing. Smash these two ideas into each other and push it a bit wider than a lunch game and you get Echo from the Dark.

Grant: What is the meaning of the title? What should it convey to the players?

Adam: It was inspired originally by Santayana: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” The factions and ideas in this game are historically-inspired factions and ideas, washed in a coat of science-fiction paint. Hopefully there’s a bit of cosmic horror lurking in there as well.

Grant: Why was this a subject you wanted to focus on?

Adam: I’m a big fan of science fiction, mostly, and the idea of the insurgent turning into an empire and needing to deal with totally new problems is a fun one to me.

If we used historical factions for this game, it’d feel more disconnected than I’d like. I appreciate designs like Imperium Classics / Legends for that kind of sandbox play, but I think using modern “empire” factions — let alone an accelerationist apocalyptic faction — would change the tone of the game pretty dramatically.

Grant: What is your design goal with the game?

Adam: I wanted to build a 4X game that my group could play at our regular game night, where not every player had to succeed at being an empire. We have players that like conflict and players that want to build their own space, and I wanted them both to have a good time.

Grant: What was it like designing a game in a series like the Irregular Conflicts Series? What challenges did the parameters of the series create?

Adam: When I started development work on Red Dust Rebellion, I asked Jason Carr to lay out a boundary: “what is the COIN Series?” RDR was going to push things pretty hard, and I wanted to be sure the final product still felt like a COIN. I did the same thing when we started talking about Echo for the Irregular Conflicts Series, and the parameters in that series leave a lot more room for exploration.

Of course, the series gives me ways to onboard existing fans, and helps people know what to expect. If I went too far away from those expectations, we’d get a lot of unhappy players. I think the challenge and the opportunity are the same: how can we look at the COIN System from a new direction to present something new, but familiar.

Grant: What opportunities did this series and your game bring for innovation and change?

Adam: It’s interesting to me how much is different while remaining familiar to fans of the series.

There are eight player factions with a dynamic setup, but each setup still distributes forces around the map to produce a tense starting situation. Every card is a technology and everyone acts each round, but the deck of cards still regulates the round-by-round tempo and the timing of victory checks.

Players still care about population, though it’s mobile and has many more possible states. Players still care about control, though the map texture is different each game and ever-shifting.

Most interesting is the kinds of strategic choices made by COIN veterans vs. those made by players new to the system — COIN folks fight more, and sooner, which leads to one type of board state, while non-COIN folks tend to split the board into pieces and race for their Victory Condition, which leads to another type of state. I’ll be excited to see the AAR’s once it gets into the wild.

Grant: What is the “history” of the universe in which the game is set?

Adam: A new resource has been discovered: “interuniversal salt,” triggering a new wave of technological advancement and conflict. Into that mélange we throw a collection of archetypical factions that pop up from time to time in human history.

At the time the game begins, expansion out from Sol has only recently begun, people are finding their footing, and the seat of power has just been attacked. The perpetrator is left undefined, but the cradle of humanity begins with chaos.

I’m working with a writer friend of mine to build up a little more flavor for things, but we simultaneously want players to be able to make their own empire and their own technocracy. Walking that line has been interesting, without history to rely on directly.

Grant: What type of setting did you want to create for your vision of the game?

Adam: I wanted a setting players could role-play in. I love grand political strategy games where players ham it up, and a big part of setting grants hooks into that kind of play. I wanted all the player factions to be human, because that gives us more room for weird non-player factions.

Another major benefit of a solid setting is that it can make rules easier to understand and remember. If you know that cards are technology, you expect to be able to research — getting players to ask reasonable questions is very important when supporting a complex game.

Grant: What type of game is Echo from the Dark?

Adam: It’s a game that should feel familiar to COIN / ICS players:

- You’ll work your way through a deck that acts as the game timer. However, the cards in that deck will look pretty different: no faction symbols, no “Propaganda” Cards, and every card is more like a Special Activity or Capability than an Event.

- You’ll lunge for asymmetric Victory Conditions that only win when checked on certain rounds. However, every faction’s victory condition has the same threshold, and non-players play as a different set of factions that can’t win at all.

- You’ll need to be efficient with prioritizing your actions, and use all the flexibility they provide. However, you grow these actions over time by researching technology and accumulating salt mines.

Grant: What main mechanics are used in the game?

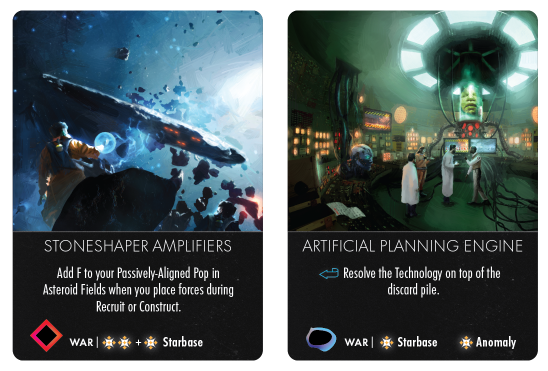

Adam: One major difference from other games in the COIN / ICS line is research & development. As technology cards emerge from the deck, players can spend their limited forces to use the special effects they grant. The player who most uses a tech will get exclusive use of it in the long run.

Grant: What are the different playable factions?

Adam: While I designed more, we’ll be releasing eight in the box: four “normal” factions and four weirder ones. In any given game, you can play with any subset, but the learn to play book will include two recommended starting scenarios that cover all eight:

- Stellar Empire, a classic COIN government faction that tends to collapse when I play it, though my developer Joe Dewhurst managed to win with it in a recent playtest game.

- Swords of the Metallic Star, an accelerationist faction that wants to burn it all down to rebuild from the ashes.

- Guild of Seekers, a trading and exploration faction that cares about building a network across the board. In current testing, they tend to win by flying under the radar.

- Asteria Collective, a tech-focused faction pushing humanity into a new golden age.

- Bronze Citadel, a military faction that builds a defensive line to hold as many sectors as they can as efficiently as they can.

- Nightstone Corsairs, a faction of space pirates profiting from the conflict at large.

- Obsidian Requiem, worshippers of ancient progenitor relics that emerge on the map randomly and dramatically shift play.

- Peregrine Initiative, who want stable popular support to free themselves up for studying the anomalies.

Grant: How did you have to balance the asymmetry in the factions to create a challenging yet balanced game?

Adam: We played with many different levels of asymmetry, and found that the really critical thing was Victory Conditions (VC): factions that were identical but for their VC felt asymmetric in a way that factions with the same VC but different ways and means didn’t.

Essentially, that means we can focus on spreading VC out over the various aspects of play for faction asymmetry, and then focus on ways and means (setup, special actions, passive effects, and components) for balance. The latter part is still in process, and will likely continue up until print based on my experience with other designs.

Grant: How do each of these powers differ in the game? What are their relative strengths?

Adam: That’s a huge question!

Powers differ by their starting position, their victory condition, their special powers, and sometimes a component or two. We talked about differing victory conditions above.

Starting positions range between having most of your pieces out to having only a few leaders. Some special powers dramatically affect the game for all factions, while others are a small tweak to your own play. One faction adds a component that permanently alters the map texture for that game.

A major part of the strategy of Echo is figuring out the strength of your faction on this map, against these opposing factions, with this technology runout.

Grant: Why does the game focus on population? Why was this important to include?

Adam: Popular support and opposition is seldom even discussed in a 4X game, but it’s a critical part of the COIN “hearts and minds” model.

I wanted the arc of the game to include population growth over time as well as the shift towards independence of distant colonies as you push them to produce. Fluid population also gives players a bunch of tools for achieving their goals.

Grant: What role does technology and its development play in the game?

Adam: Every one of the 48 cards in the game is a technology, and you’re likely to see less than half of these cards in any given game. Further, cards stay available for use until the next Entropy Round (where victory is checked), and then continue to be available for the player who used them the most.

Each technology also determines where Salt shows up on the map, where the non-player factions emerge, and where disasters may happen. This means that the arc of each game is heavily dependent on that game’s specific run-out of technology. A game that sees more black hole or War-oriented technology will be significantly different from one with more anomaly or Recruit-oriented tech.

Grant: What different types of technology are included?

Adam: Many different types. First, technology has a sector type. Anomaly tech has a different feel to its effects than Nebula tech. Second, technology has an associated action. Recruit tech is different from War tech. Third, technology is stronger when you can spend some Salt.

Grant: What different types of cards are included in the game?

Adam: In a sense, there’s only one type of card: Technology. If you think of them as Special Activities smashed into Capabilities and Events, you’ll get the right idea.

Grant: What is the framework for how the Event Cards work with events, eligibility and turn order?

Adam: Echo from the Dark uses a Sequence of Play similar to A Gest of Robin Hood, where taking a big action one round means you’ll go later in the next round. This was necessary after deciding each game would include a subset of the eight factions — we couldn’t put faction icons on the cards even if we wanted to.

Furthermore, each faction acts on every round. This means that you’ll tend to go through fewer cards (because each one is equivalent to two COIN-style rounds of play), and initiative matters much more. You don’t see the upcoming card, but going earlier gives you other important options and acts as a tie-breaker for Technology control.

Finally, we don’t shuffle anything special into the deck. When there’s no place to put a card on the Technology display, you check for victory and do some cleanup. This gets folks into the game quite a bit faster, and also means that you can see the end coming — I really like what it does to tension.

Grant: Can you share a few examples of cards and explain their use?

Adam: While specific effects are still subject to change during the development period, some popular technology effects include:

- Activating a sector for the same action multiple times.

- Using Chaos (kind of a combo of Active Opposition and Terror markers) to fight.

- Copying population markers.

- Long-distance movement.

- Making other players’ actions more expensive.

Grant: What actions do the players have access to? How do the actions work?

Adam: Because we have a bunch of factions, I wanted to reduce the asymmetry in basic actions to help simplify “the teach.” Every faction shares the same four basic actions:

- Recruit: Place your Leaders and bring the population into alignment with your faction.

- Construct: Place new population, build starbases, and build fleets.

- Navigate: Move forces and population to adjacent sectors.

- War: Remove enemy forces and push the population down towards chaos.

COIN players will recognize that Recruit feels a bit like a Rally action, Construct might look like Train, Navigate is a pretty reasonable March, and War is kind of an Assault. However, a major difference is our population representation. In Echo, each pop is a piece. They’re placed, moved, replaced, and removed.

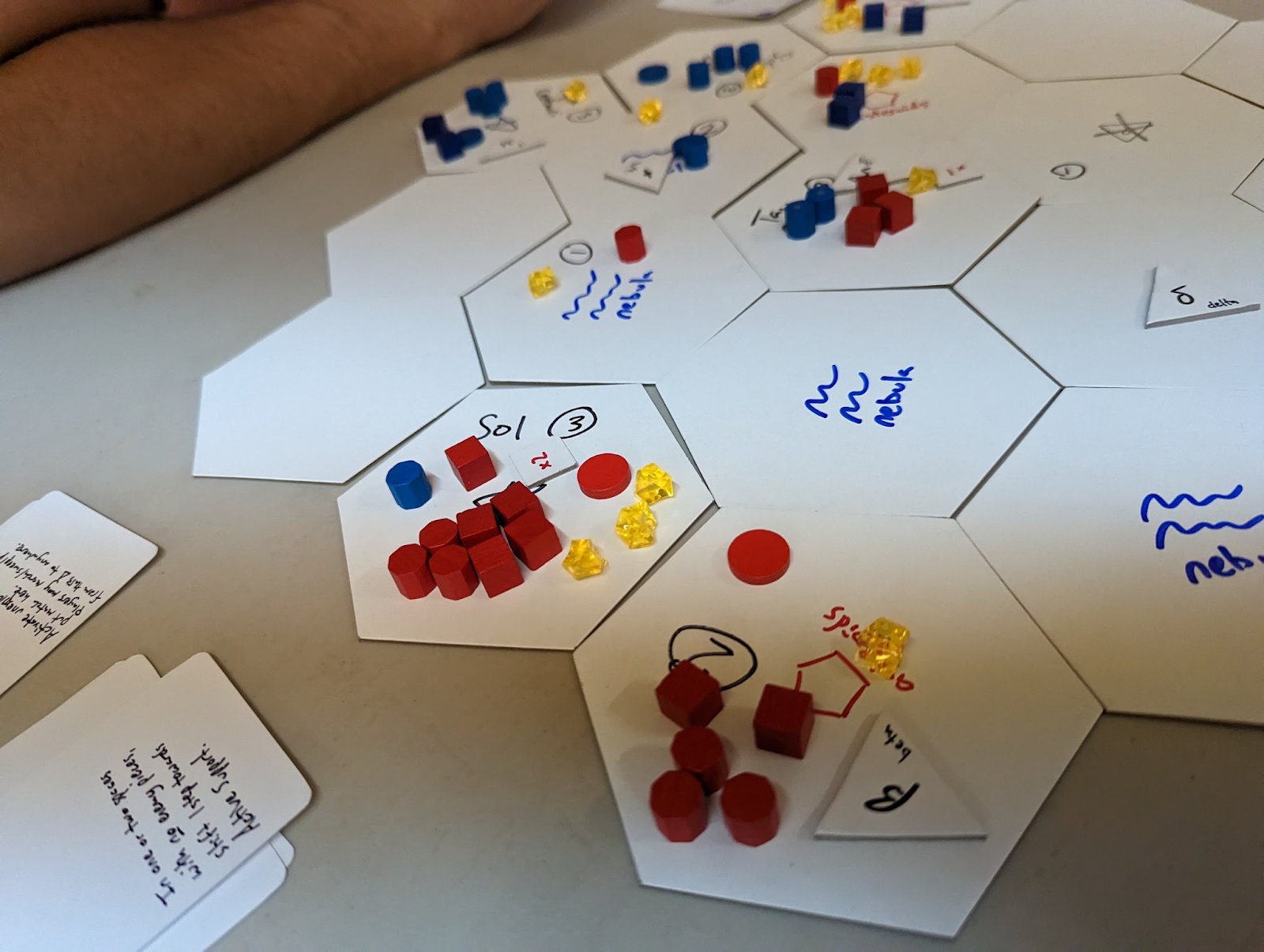

Grant: What is the layout for the board?

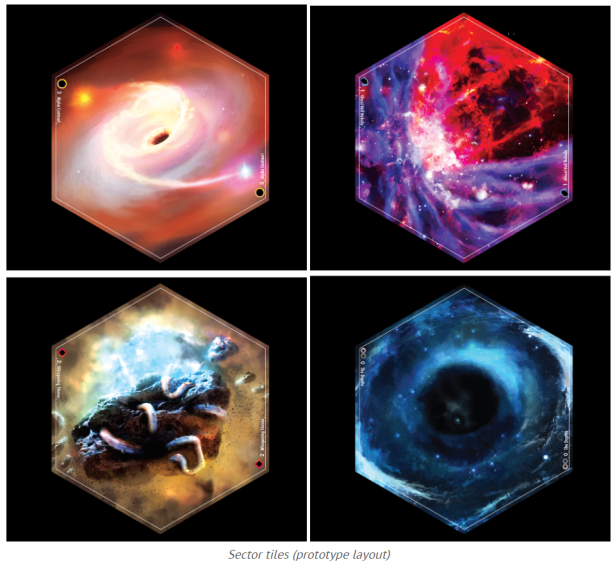

Adam: The map is built of 19 hexagonal Sector Tiles, laid out semi-randomly for each game. Each Sector has a type that determines how easy it is to live there and what technology will be discovered by its researchers.

As we’re using a subset of the playable factions in each game, on a randomized layout, players choose factions and place forces after seeing the initial map.

Grant: How are Sector Tiles determined? What different types are included?

Adam: All the Sectors are included in each game, though because movement is pretty slow without Technology, the distance of a Sector from the “Core” (around Sol’s fixed location) can dramatically change how impactful a given sector is from game to game.

A game where all the black holes are far from the Core Sectors is very different from one where the Core is surrounded by three black holes.

Grant: How does combat work in the design?

Adam: War is expensive. It’s pretty cheap to remove a single enemy force, but large-scale conflict costs more and more fleets to execute. Destroying a starbase drops the population down towards chaos but some factions will also target them directly. Furthermore, Technology gives you ambush opportunities and additional ways to cause damage.

Grant: How do players obtain victory?

Adam: As in other games in the COIN and ICS line, each faction has a victory condition that adds some game state up towards a specific threshold. Some conditions additionally have special tracks, like the Empire’s “Decadence” Track filled up by taxing the population.

These conditions are checked every so often, so you may need to maintain them for some time before winning the game. In the current prototype, we’ve balanced the conditions so they can all have the same threshold, which makes it easier to see who’s winning and by how much.

Grant: What type of an experience does the game create?

Adam: In my group, this straddles the line between a mean, strategic, “plans within plans” experience and a funny, role-playing, speech-giving experience. There are moments when the table doesn’t know what might happen, and moments when everyone bands together against a common threat. I’m pretty happy with it!

Grant: What are you most pleased about with the design?

Adam: It works! I’m excited to see both COIN veterans and 4X veterans approach the system differently but still both have a good time with it. I’m also very happy about how easy it is to teach, as I bounce between conventions running demonstration games.

Grant: What has been the response of playtesters?

Adam: People want to play again: “Looking forward to seeing new iterations.” “oh man, this is frickin cool” “Had a great time!”

Whenever I run demos I get requests afterwards for playtest access, and I have lots of extremely helpful folks sending me questions and proofing notes and ideas. In particular, my local group hasn’t forced me to throw it out the window yet, so that’s a big plus.

Grant: What other designs are you working on?

Adam: Two that I’m ready to talk about here:

An operational-level Napoleonic chit-pull game. I don’t really have a title for this that I’m happy with, but the core system is quick and fun and pointed. The idea came from exploring how a system might be able to cause Mack’s collapse at Ulm in the 1805 campaign, without resorting to “dummy” rules. The devil, of course, is in the details.

A game about the wine industry in the Pacific Northwest. I live within ten minutes of over a hundred tasting rooms. It’s a very weird place to be, and the history that led to these wineries is fascinating: lots of cooperation and network effects, for one. Hopefully we can get a prototype of this to GMT’s Weekend at the Warehouse this fall.

There is a lot more to read about the game on the game page at the GMT Games website but it looks so very interesting and I have been following its design over the past year or so after seeing a few pictures of the game in action at Circle Con put on by Fort Circle Games. I want to thank Adam for his effort in answering our question and whish him the best of luck in the final development work on the game.

If you are interested in Irregular Conflicts Series Volume 4: Echo from the Dark, you can pre-order a copy for $85.00 from the P500 game page at the following link: https://www.gmtgames.com/p-1144-echo-from-the-dark.aspx

-Grant