We love Labyrinth here at The Players’ Aid and have played each of the expansions many times. We love it and I am very much interested in this new expansion, which is a prequel of sorts called The Rise of Al-Qaeda, 1993-2001. Labyrinth: The War on Terror, 2001-? is just such a juicy and amazing asymmetrical Card Driven Game that pits the mighty and powerful United States military and all of its various antiterrorist agencies against the Jihadists in the Middle East whose sole goal is to spread terror, sow the seeds of deceit and ultimately destroy Western civilization. We reached out to the designer Peter Evans to see if he was willing to answer our questions and he was…with great enthusiasm which we very much appreciate!

*Keep in mind that the design is still undergoing playtesting and development and that any details or component pictures shared in this interview may change prior to final publication as they enter the art department.

Grant: Peter welcome to our blog. First off please tell us a little about yourself. What are your hobbies? What’s your day job?

Peter: My hobbies include gaming, of course. I’ve been a lifelong computer gamer, and I got into board games around 2010 – the first I bought were Twilight Struggle and Labyrinth, quickly followed by Andean Abyss. Most of my small collection still comes from GMT Games, and I’m obviously still a fan of CDG’s! Other activities I enjoy include visiting museums and galleries, walking, reading, and yoga. I also enjoy travel. I spent a week in Florence, Italy in October last year and I’d love to go back.

In terms of day job, I have three hats. I work at a University four days a week supporting PhD students, with a fifth day spent on design projects and freelance development, supplemented by teaching yoga a few evenings each week.

Grant: What motivated you to break into game design? What have you enjoyed most about the experience thus far?

Peter: After I finished my PhD in History 10 years ago, I felt a gap. Game design fills that space. It provides big projects that scratch a few of the same itches. I enjoy research and pushing myself to understand complex subject matter. It’s a good workout for my brain.

Historical game design raises a lot of the issues that preoccupy historians – such as how to represent the past (and whether to, and why), frame our stories about it, and explain why things happened as they did (if we even can).

I use design as a vehicle to deepen my understanding of political processes. My efforts so far have been directed toward insurgencies, elections, and international relations / diplomacy (my “grail” game topic is the Cold War).

Grant: What lessons have you learned from your work as a staff developer that have helped in your own design efforts?

Peter: Seeing and assessing a lot of designs helped me overcome some of my design shyness. It encouraged me to make my own pitch, and earlier on in the design process. I have a tendency toward perfectionism, which can manifest in over-research – I do like to get things as “right” as I can – but designers need to embrace the fact that people may not agree with (or understand) your choices, and that that’s OK: “you can’t please all of the people all of the time”. For me, it ultimately comes down to whether you act in good faith.

Working as a developer also has helped me hone my analytical skills, as did volunteering as a playtester (which I’ve done for much longer, and I still help GMT with some designs).

Most importantly, though, working with and for GMT has provided me with community. Being part of a group of developers, testers, and designers has given me a great support network.

As with any creative project, game design involves putting yourself out there and opening yourself up to criticism, which can be difficult! It’s really valuable having trusted people who can provide a sounding board, and point out things you may have missed. In terms of the lesson there (per your question), I’d say it’s that networking is very important!

Grant: What roles do you and your developer Marco Poutre play? How do you enhance and balance the design experience?

Peter: The role of a developer is akin to that of a book editor, whilst the designer is the author. With Rise of Al-Qaeda I designed the card deck, new mechanics, and new pieces; whilst Marco provides feedback and ideas. Developers need to have a good eye for logic – for example, “will this break anything?”; “can we parse it logically, with a reasonable rules overhead?”; “are we using terms and concepts consistently?”. They also need to have one eye on the gameplay, of course. Marco will be organizing our playtesting very soon. He’ll also be responsible for liaising with our colleagues in the art department when we get there.

Grant: What is your new upcoming game Labyrinth: The Rise of Al-Qaeda about?

Peter: The subtitle says it, really. It’s a prequel expansion to Labyrinth: The War on Terror, about the rise of Al-Qaeda in the context of Jihadist movements (primarily Salafist) in the period building up to 9/11.

A diverse and fractured set of movements united by similar goals and ideologies, these groups were waging insurgencies to try and topple regimes across the Middle East and replace them with governments adhering to their vision of Islamic rule.

Some of these regimes were US clients, like Egypt and Indonesia, to whom the US provided aid and indirect support. One of the things the game is saying, therefore, is that 9/11 occurred in a specific context, and that the “War on Terror” marked a distinct phase within a broader history of the United States’ geopolitical engagement with the Muslim world.

Grant: What time period is covered by the game?

Peter: The full 3-deck game covers 1993 to 2001, so between the two World Trade Center attacks. There are also two shorter scenarios. The 2-deck 1996 scenario starts after Bin Laden’s “declaration of war” while the 1-deck 1998 scenario starts after the US Embassy Bombings.

Grant: Why was this the subject you wanted to focus on with your first design?

Peter: This wasn’t my first design! Far from it. This is just the first that’s seen the light of day. I have several attempted COIN’s in the graveyard (that’s a hard system to get right, despite looking quite friendly to beginners), alongside a few others. I also have several other ongoing projects that are in various stages of completion, most of which predate this one.

As to why I chose to invest in this project as my first offering on P500…partly it’s personal interest. Geopolitical and geostrategic themes appeal to me. Partly, because it’s easier to work with an existing system – the limits that are imposed are good ways to build confidence. Partly, though, it’s because after I tried the idea out and thought it would work, Jason Carr (Lead Developer at GMT) encouraged me that it was a project GMT would be interested in.

The project grew out of a design challenge I set myself to improve my skills, answering the question “what would need to change about Labyrinth in order for a prequel to work”? When I tested my first prototype, I was surprised at how I quickly found that the answer was “not as much as you’d think”. That’s when I realized it could be more than just an exercise for me.

Grant: What must a prequel to the original Labyrinth include and model?

Peter: The most obvious thing is the difference in context between the pre- and post-9/11 worlds. There was no “War on Terror” in the 1990’s, of course. However, Labyrinth is conducted at such a scale of abstraction that less needs to change here than you might think.

Labyrinth is a geopolitical game – it’s about insurgencies and counterinsurgencies across the different countries depicted, much more than it’s about terrorism and counterterrorism.

As the Coalition player you’re still going to Disrupt cells, conduct diplomatic efforts in an effort to secure the resources of the Middle East (through what the game models as “good governance”), and deploy Troops to maintain stability. The Jihadist still operates through cells, aiming to conduct Major Jihads (coups and revolutions), and carry out Plots in order to raise their standing and secure access to more funding.

Some aspects don’t quite align, however, these are often aesthetic. For example, we’ve had to keep phrases that would be awkward to change in the game – like having a “Global War on Terror” track, and the idea that diplomatic activity constitutes a “War of Ideas”. Still, even if the terminology better suits the 2000’s at times, the function of these mechanics works for the 1990’s. It helps that the Bush Jr. administration inherited much of the strategic framework used in the War on Terror from the Clinton era – for example, the fundamental idea that the way to defeat insurgencies is by providing “good governance” (and, in turn, Clinton’s era had a lot of continuity with Bush Senior’s as well).

The second big thing is that the Jihadist movement was split between those who advocated a “nationalist” and those who urged an “internationalist” strategy. Bin Laden belonged in the second camp, which was the minority view until 9/11, really. It wasn’t until then that he was able to assert a claim to the moral leadership of the Jihadist movement, and inspire further attacks against the “far enemy” (even if most activity took place within the Muslim world).

Whilst Bin Laden never had full command and control of Al-Qaeda – and Al-Qaeda never exercised central command of the various Jihadist movements around the world – the movement was even more fragmented in the 1990’s. So, I needed to make sure that distinction is clear in the game. We primarily do this through the design of the card deck, and a new “guerrilla” piece/mechanic. These are the Jihadist’s equivalent to the militia pieces introduced in Awakening. They help you in civil wars, and contribute to your piece count for Major Jihads, but you can’t use them for other Operations (e.g. move them).

I could go on about this – but I’ll save some for later questions.

Grant: What was it like designing a game in an established system?

Peter: Easier in many ways. Game systems need to be robust, and Labyrinth’s is definitely that. This gives you something firm to base your decisions on. It’s useful to have preexisting limits to work with, and within. The questions you face as an expansion designer are therefore more limited, iterating on what comes before. That said, you can still ask yourself things like: “How could I represent or model something the original game didn’t?”; and “How should I code different types of historical events as card effects?”, for which it helps to develop a set of sensible rules. For example, I decided that events representing plots should have effects based on the game’s Plot mechanics. Once you have your rules, ideas can flow quite easily from there, and you know you’re on firmer ground in terms of representing the dynamics and processes of history. That’s been my theory and approach anyway.

Grant: What design challenges did you have to overcome? How did you overcome them?

Peter: Plenty. One example is the changing of the base game’s Victory Conditions for the Jihadist, one of which is to conduct a successful WMD Plot in the United States. Clearly, that doesn’t make sense for an era that culminated with 9/11 (i.e. not a WMD attack).

However, 9/11 clearly marked a success of the objectives of Bin Laden’s “internationalist” wing of the Jihadist movement, so the question arose of how to represent that in the game? After trying a few different iterations, we’ve settled on allowing Plot 3 to trigger victory, on the basis it represents an attack on the scale that Al-Qaeda sought to – and did – achieve.

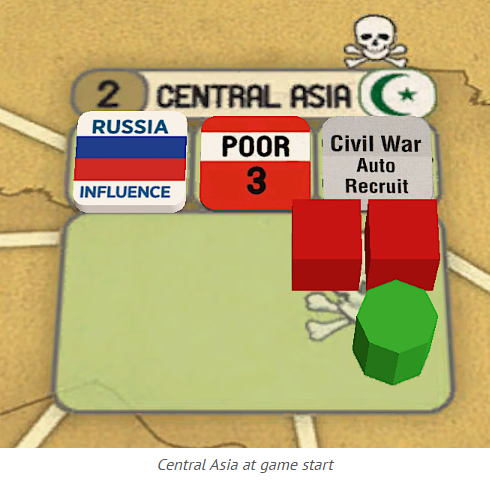

A second challenge was how to prevent the Jihadist player from having free reign in spaces where it’s not that easy, or historically reasonable, for the Coalition to intervene. Places such as Central Asia and Chechnya, and the anti-American regimes in Libya and Syria (Iraq is treated differently in the game, becoming a special case country like Iran). I noted that these are all areas of strong Russian influence historically, which led to the development of an historically relevant solution – Russian Influence markers, and Russian Troop pieces that can deploy to protect those spaces (see below).

A third challenge was that I needed a system to represent WMD’s appropriately in this era. After researching WMD proliferation in the 1990’s, I quickly realized that the two systems could dovetail (at least the part of WMD’s not tied to Iraq). WMD markers now function to protect regimes who have them. Since we have reasonable grounds to believe Libya and Syria had stockpiles of chemical weapons they might use against insurgents in the 1990’s (as indeed Syria did, repeatedly, in the 2010’s), they’ve been repositioned to those spaces. This dovetails nicely with the desire to protect those spaces, even though it emerged as a solution from the history. But note, once I had sound criteria for where WMD markers should be placed, and it became obvious that Egypt also matched those requirements, I made sure setup places a WMD marker there, too.

Grant: What sources did you consult for the historical details? What one must read source would you recommend?

Peter: I’ve used a lot of sources. Since I work at a University, I have the privilege of being able to access academic articles as well as publicly available sources. I’ve also worked hard to give the design a reasonable grounding in up-to-date scholarship.

To see my recommendations, I published a shortlist on BoardGameGeek last year: https://boardgamegeek.com/thread/3393332/any-questions (5th post).

Grant: Are you concerned about the game being seen negatively due to the connection with 9/11? How have you dealt with this subject?

Peter: The big question. I can understand why people would react negatively. 9/11 sits in a category of its own when it comes to terrorist attacks, and there is a need for sensitivity.

The first thing I want to say is that although (as with base Labyrinth) the Jihadists are seeking to conduct a major attack in the US on that scale, 9/11 itself is never explicitly referenced.

Second, oversimplifying somewhere, in relation to 9/11 my purpose is to place it in context. I want to be very clear that this is not “a game about 9/11”. It’s a game about the geopolitical and ideological conflict within which 9/11 occurred (and may occur). From the Jihadist’s perspective, the conflict Westerners call the “War on Terror” did not start in 2001. They already thought of themselves as fighting a war against the US led West. Bin Laden explicitly declared war on the US in 1996, but he was working toward that end in response to the deployment of non-Muslim soldiers in the Arabian Peninsula during the Gulf War.

Jihadists turned to this “internationalist” strategy of striking the “far enemy” (the US, and allied regimes outside the Muslim world) in the face of the failure of the “nationalist” strategy that had prevailed in the 90’s. As I briefly mentioned above, prior to Al-Qaeda’s attacks on American targets beginning in 1998, Jihadists had focused on fighting the “near enemy”, secular regimes in the Muslim world, and most especially Egypt and Algeria.

It is no coincidence, for example, that Ayman al-Zawahiri became Bin Laden’s second in command. In the 1990’s he had been the leader of Egyptian Islamic Jihad, a group dedicated to the overthrow of the Egyptian regime, and he joined Al-Qaeda partly because EIJ failed. This, then, is the story the prequel tells – of the strategic failure of the Jihadists to overthrow regimes in the Middle East, and their consequent turn to spectacular acts of terrorism.

Like base Labyrinth, therefore, Rise of Al-Qaeda is focused on portraying the larger strategic goals of the two sides, and actions taken by two opposing coalitions in a series of conflicts between various Jihadist groups and the US-led West (or sometimes Russia).

The last thing I want to say here is that wargaming that depicts atrocities are probably always going to be controversial. For me, the fact that a subject is horrifying doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t engage with it. I believe the opposite: it is precisely why we should engage with it. If the question is “why create games about such events and activities?”, my answer that we produce, and engage with, this kind of content in order to better understand it.

As for why a game, specifically? For me, it’s because games uniquely have the ability to place people in a situation of agency, within a system where you can see the moving parts. Done properly (and I would argue this is much harder than it seems), games can provide a complementary educational tool to traditional narrative histories. At the least, games can serve as useful entry points in introducing people to a topic and encouraging further engagement, but at their best they help can encourage a deeper understanding.

Grant: How does this expansion build on The Awakening expansion?

Peter: I’ve taken several of Awakening’s mechanics and applied them “back” to the prequel. First, Awakening’s inclusion of civil wars enhanced Labyrinth significantly as a game and a model by creating a political dynamic that sits outside of the direct control of the players. Likewise with the political movements and agitation represented by “Awakening” and “Reaction”.

The 1990’s was marked by a series of brutal civil wars and insurgencies across the Muslim world – in Algeria, Somalia, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and with an added separatist dimension in Bosnia, Kosovo, Chechnya, Kashmir, Indonesia and the Philippines. The role of Islamists/Jihadists varied in each, but they engaged in all of them. It makes sense, therefore, for Rise of Al-Qaeda to use the civil war mechanics, including Militia pieces from Awakening.

Regarding Awakening and Reaction markers: tensions and conflicts between (and within) progressive and reactionary groups in Arab and Muslim societies obviously predate 2010. Take Algeria for instance, which fell into civil war in 1992 after the secular government refused to cede power to an elected Islamist party. Other examples include the role of Islamist parties in Chechnya and Tajikistan, and the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt. Again, therefore, it makes sense to include these elements in the prequel. Even though the 1990’s weren’t a period of mass mobilization across the region as a whole, the dynamics Trevor sought with rules such as Polarization and Convergence still plausibly apply.

In Rise of Al-Qaeda, Reaction and Awakening markers still represent political parties, movements, and other actors aiming to shift their governments toward or away from a more Western, liberal, orientation on the one hand, and “Islamist rule” on the other. However, they will come onto the board in smaller numbers, and I’ve designed plenty of opportunities to remove them through card events. (Note that the name of Awakening pieces is another instance where the language doesn’t quite fully align, but we have kept the existing terminology for ease and familiarity.)

Grant: What are some of the differences in how the US fought against Islamist terrorism in the 1990’s as compared to the original Labyrinth period?

Peter: From one perspective, counterterrorism was very different. The most striking thing being that it wasn’t an effort that saw much direct US military involvement. US policy in the 1990’s defined terrorism as a question of law enforcement and criminal justice – the responses to the 1993 WTC attack in New York and the 1998 US Embassy Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania for example were led by the FBI. They resulted in criminal proceedings: terrorists were arrested, interrogated, tried, and imprisoned via existing legal processes. Defendants were given top defense lawyers to argue their case. This approach had emerged in the 1980’s – Clinton adopted it directly from Bush Senior (Director of the CIA when it was introduced).

Taking a different perspective, though: actions in Labyrinth are sufficiently abstracted, and occur at such a large scale, that they still make sense in the context of the game. Labyrinth’s Coalition player has an action called “Disrupt” used to locate and remove terrorist Cells. In the prequel, the Coalition player still uses this operation, and they’re still using a mix of intelligence assets, law enforcement and security forces to find and fight them. The same applies across the Ops menu of both sides. Volko already gave each player the tools they needed to wage the kind of geopolitical struggle that the game depicts.

And that’s the thing. Labyrinth games have actually always been more about how the US fought against Islamist insurgencies than against “terrorism” per se (although there’s much to say about the erosion of a clear distinction between the two in this era).

Grant: I see a lot of similarities here to the original game and its expansions. What can we expect to see that is different?

Peter: Many new mechanics and pieces are included. I’ve elaborated on each in answer to further questions below. In summary, the new elements introduced by the prequel are:

- Guerrillas

- Regional powers (Russia and China)

- A WMD overhaul

- Plot 3 Victory (a successful Plot 3 in the US is now sufficient for the Jihadists to win).

- New Country mats

- “Hybrid” Countries

Grant: What is the makeup of the new 120-card Event Deck?

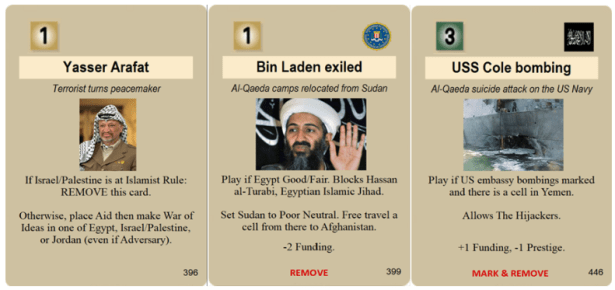

Peter: I’ve adopted a systematic approach to design the cards included in the deck. As usual, the deck contains notable headlines from the period, but I’ve also taken pains to make sure I’m representing the most relevant events, not just the most noticed. So, the list of relevant Jihadist movements I’ve included cards for, and the Ops value of those cards, as well as their event texts, are based on how large and active they were, and their tactics.

For example, the GIA are a 3 Op card because they were large and carried out many attacks; their event text is based on their tactic of committing massacres to undermine the regime; as they used the same approach, the same event effect is also assigned to the EIJ card.

This is then cross referenced against the needs of the game. It was important to me to make sure cards were included to represent events across the whole map. Therefore, there is also a “Massacres” representing other movements who used the tactic, which was widespread.

Coalition events are divided into:

- Agency cards (e.g. CIA, FBI, or the IMF)

- Allies (e.g. Ahmad Shah Massoud, Hosni Mubarak)

- Operations (e.g. Operation Allied Force, UNOSOM II)

- Peace Treaties (e.g. Dayton Agreement, Oslo Accords).

Jihadist cards are similarly divided into:

- Al-Qaeda personnel (e.g. Bin Laden, Ayman al-Zawahiri)

- Other leaders (e.g. Saddam Hussein, Shamil Basayev)

- Al-Qaeda affiliated groups (e.g. Al-Jama’a al-Islamiyya, the EIJ)

- Other Salafi groups (e.g. Takfir wal-Hijra)

- Other Islamist groups (e.g. Al-Qassam Brigades, the GIA)

- Broader Muslim guerrilla movements (e.g. Free Aceh Movement)

- Plots (e.g. Bojinka Plot, USS Cole Bombing)

- Political events (e.g. Black Hawk Down)

- There’s also a card called Ambush, which the US wants to draw, as it harms the Jihadist.

Neutrally aligned cards follow the same kind of pattern:

- AQ personnel (who can be removed by US play, e.g. Omar Abdel-Rahman)

- Leaders (who can be removed by US play, e.g. Omar al-Bashir)

- Agencies (which might benefit either side, e.g. Pakistani ISI, Russian FSK)

- Proxies (e.g. Resistance Brigades in Lebanon, the Revolutionary Guards)

- Minor Salafi Jihadist groups (e.g. Aden-Abyan Islamic Army, Al-Ittihad al-Islami)

- Political events / Operations (e.g. Kofi Annan meeting Saddam Hussein, Repression)

Grant: What are the new guerrilla pieces? What do they represent and how are they used?

Peter: Guerrillas are Jihadist pieces that act like Militia in Civil Wars. But they also contribute towards the count of Cells when calculating whether a Major Jihad is possible. As noted above, they represent local forces not entirely under the control of the Jihadist player, and are dedicated to the overthrow of “near enemy” regimes (the “nationalist” strategy).

Grant: What roles do the Chinese and Russian Influence tokens play in the game?

Peter: You’ll find Russian influence in Libya, Syria, Serbia, Caucasus, and Central Asia; Chinese influence in Pakistan. They add +1 to Jihad rolls, representing the support these regional powers will provide to defend their allies. They also block WOI attempts if their parent country is at Hard posture, which represents that the regional power and their client regime are not willing to cooperate with the US-led Coalition. This forces the Coalition to conduct WOI in Russia or China before they can do so in affected spaces, so it’s more important for the Coalition to keep them on-side.

Russian Influence also allows a country to host Russian Troop pieces – think real-life Syria. Russian Troops are very similar to Militia.

Grant: What are the new rules for Civil War? What do you hope to model with these rules?

Peter: The rules are the same as Awakening, except a modification to account for Russian Troops. A hit inflicted by the Russians that can’t be absorbed by a Cell or Guerrilla will end a Civil War, rather than shift Governance or Alignment – they won’t ally a space to the Coalition.

Grant: What are the new rules for WMD plot markers? Why was a change needed?

Peter: WMD markers now add +1 to pieces needed for Major Jihad. This change in the model is based on the only actual use of WMD’s in this region across in the entire period of the Labyrinth Series, during the 2011-2025 Syrian civil war. There, they were deployed in defence of the Assad regime several times. WMD Plots still become available for the Jihadist as a result of a successful Major Jihad (or an Attrition roll when they are undefended!), but they’re now a little harder for the Jihadists to get hold of, because regimes will use them!

As noted above, 3 WMD markers are now placed in countries which we can reasonably believe had stockpiles of chemical weapons at the time: Libya, Egypt, and Syria, none of whom had signed non-proliferation treaties. Unlike countries that inherited Soviet WMD’s (and only Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan really had any of note anyway), these were countries interested in maintaining their stockpiles, and who had not renounced their use.

Grant: What does the new card-driven subsystem represent? How do players interact with it?

Peter: Following on from the above, the answer is Iraqi WMD’s. The other 3 WMD markers go in Iraq, and interact with several cards representing UNSCOM efforts to disarm the country.

The other subsystems are Al-Qaeda Plots, and FBI Most Wanted cards. For these, certain cards are marked with icons indicating they can be retrieved from the Discard pile through the play of various Events. Al-Qaeda leaders allow major plots to be fished out, whilst the FBI event can trigger the US effect on Neutral-aligned terrorist cards (see below).

Grant: What opportunities did this new card-driven subsystem open up for the design?

Peter: The Iraqi WMD system is a source of Prestige gain/loss for the Coalition, because it was important for US engagement with the region, but only tangential to the Jihadist movement.

The Plot icons have allowed me to structure the major Al-Qaeda plots so that they happen, and don’t just disappear into the discard in shorter 1- or 2-deck games. Attacks like the USS Cole Bombing are so important to the narrative of the prequel that I needed a way to make them more likely to happen than the traditional “prerequisite” system CDGs use.

FBI Most Wanted meanwhile provides a way to neutralize terrorist operatives without solely relying on the luck of the draw. The FBI card can either be useless as an event, or offer a wide range of tactical options, depending on the circumstances.

Grant: How can several of the new systems be brought “forward” in time into the later games?

Peter: First, you can play a Campaign game through from the prequel on into later games and simply keep most elements in play. Second, there are rules for how to set up later scenarios with the new components.

The new WMD rules, including Plot 3 victory, can easily be retained and integrated in later games, and the same is true of Russian and Chinese Influence, and the new Country mats. They can all just stay in place, or be added to existing games

Guerrillas require a little more thought. One of the few design tasks remaining on my list is to test out different options, but I’m leaning toward instructing players to place Guerrillas rather than Cells when a Country with Reaction markers falls into Civil War.

Grant: What new experience will this create for the players?

Peter: I’ll quote my lead playtester, Calvin Kirkpatrick, for this one:

My favorite part is probably the way that the decreased Ops-per-hand makes one more observant of the game board. In order to progress towards your goals, you need to take advantage of Besieged Regimes, Aid, Awakening, and Reaction. Instead of creating the crisis, you are taking advantage of the crisis, which fits very well with the pre-9/11 mood.

As Calvin points out here, the Ops balance of the prequel deck is skewed on the low end. But Rise of Al-Qaeda also skews the Coalition player toward a Soft posture.

The bluntest instrument I use for this is that the “US Election” event from the other games has been replaced with one called “Election Cycle”. That auto sets the US Soft. This is compounded by the relative lack of availability of 3 Op cards, making it more difficult for the Coalition to change Posture and conduct Regime Change. It’s not impossible, but it’s a hefty investment and the rest of the world is likely going to be Soft.

On top of this, the Coalition player starts the 1993 scenario with Regime Change in Bosnia/Kosovo and Somalia, representing UN peacekeeping missions; and another element that strongly contributes to creating the experience Calvin describes is the Scenario set-up. Rise no longer has untested Muslim countries. Instead, there’s a much more clearly defined set of geographical constraints. In terms of the game’s model, my argument here is that Americans know who its friends are in this region, and where they can invest/trade safely, as well as who their enemies are (it’s 1993, not 1793!).

The sum of these new conditions, in addition to the mechanical changes already described above, results in the experience Calvin describes. In my experience this means Rise has more viable strategies than the previous games in the series. The whole board is active, and each area has its advantages and drawbacks. The Coalition has a lot of fires to put out, and usually have to play defense before they can pursue their own opportunities. The Jihadist has many opportunities, but can’t pursue them all. But I’ll save writing about strategies for future articles.

Grant: What are the new Country Mats and what do they represent?

Peter: The New Country Mats are:

- Bosnia/Kosovo (Muslim, non-Shia mix)

- Caucasus/Chechnya (Hybrid, Sunni)

- India/Kashmir (Hybrid, Shia-mix)

- Israel/Palestine (Hybrid, Sunni)

- Iraq (Special Case, like Iran).

Bosnia/Kosovo is a Regime Change at the start of the 1993 scenario. The Regime Change marker represents UN efforts to stabilise the regime in Bosnia.

Caucasus/Chechnya obviously represents Chechnya, although the Muslim component also represents Azerbaijan. It’s an Oil space, as Chechnya sits astride major pipelines into Russia from Baku. The others, I think, are obvious.

Iraq is a special case country because Saddam’s regime is secure, and the UN is attempting to disarm the country of its WMD’s after the Gulf War.

Grant: What Bonus Cards for the base game of Labyrinth are included? How do they change that volume?

Peter: These cards allow the new WMD rules to be applied into the base game, whether as part of a Campaign, or just to change the dynamics of the original scenarios.

I haven’t finalized the replacements cards yet, and I do have to keep some things back…but I am very grateful to Volko for agreeing to let me include these!

Grant: What are you most pleased with about the design?

Peter: How lots of small changes intended to model specific dynamics and/or solve specific problems have come together as a working system. Also that this produces a very different feel to other games in the series, as Calvin outlined above.

Grant: What has been the experience of your playtesters?

Peter: We haven’t started playtesting outside of a group connected with GMT yet, but those who have played it like it a lot. Marco (the game’s developer) has helped clarify card effects and gives me a great sounding board for when I need to dial something up or down. He also keeps his eye on whether events are sufficiently interesting for players.

Another GMT Staff Developer, Joe Dewhurst, recently helped me reshape how Israel/Palestine worked. This resulted in the new “Hybrid country” mechanics, and allowed me to add India/Kashmir to the game. Which was something I’d wanted to do, but hadn’t been sure how until then.

I’ve also had great feedback regarding the overall dynamics I want to achieve from fellow designer Stephen Rangazas. Among other things, Stephen is excellent at providing a sounding board, and a sense check for ideas.

Finally, I’d like to make a special shout-out to thank Calvin Kirkpatrick who I quoted earlier. He’s been really fantastic. I met Calvin through the unofficial COIN server on Discord, and he’s been great at helping me think through event effects and mechanical changes, as well as issues when I update card texts and the Tabletop Simulator module. I’ve really appreciated his input and his enthusiasm, driven by his deep interest in the subject matter.

Grant: What other games are you working on?

Peter: My main effort is an election game on the US Presidential election between Truman and Dewey in 1948. The greatest election comeback of the century! I’d really recommend looking into it, and perhaps picking up a book like A.J. Baime’s Dewey Defeats Truman (2020). That era was pivotal in shaping the contours of postwar America up until Reagan, and laid the foundations of the great realignment of US electoral coalitions.

I’ve also done the research for a couple of other games that still need mechanics designed. These were originally based on existing designs, but I’ve decided I want to do something different with them. One is about negotiating the Peace of Westphalia (who doesn’t want to delay negotiations because one simply must be referred to as “Your Excellency”?); the other about the 1830 revolution in Paris (the one depicted in Delacroix’s Liberty leads the People).

Thank you so much for your time in answering our questions Peter! I am a huge fan of the system and just love Labyrinth and anything using the system. I am very interested to see how this all turns out and how it changes the experience.

If you are interested in Labyrinth: The Rise of Al-Qaeda, 1993-2001, you can pre-order a copy for $37.00 from the GMT Games website at the following link: https://www.gmtgames.com/p-1143-labyrinth-the-rise-of-al-qaeda-1993-2001.aspx

-Grant