We became familiar with the work of Javier Romero when we played his game Lion of Judah: The War for Ethiopia, 1935-1941 from Compass Games in 2017. Since that time, we have done 5 designer interviews with him for World War Africa: The Congo 1998-2001 in Modern War No. 52 from Strategy & Tactics Press, Soviet Fallout: The Nagorno-Karabakh War: 1992-1994 in Modern War No. 54 from Strategy & Tactics Press, Santander ’37 from SNAFU Design, The Chaco War, 1932-1935 in World at War #86 from Decision Games and Caporetto: The Italian Front 1917–18 in Strategy & Tactics Magazine #337 from Decision Games. A few months ago, I saw where Javier was designing a game on the the Bosnian War in the mid 1990’s and I immediately reached out to him and he was more than willing to talk with us.

Grant: What historical period does your new game Bosnian War cover?

Javier: The longest and bloodiest conflict of the so called Wars of Yugoslav Secession of 1991-2001 – the Bosnian War, 1992-95. The Bosnian War was the result of the self determination process that followed the breakup of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union. Three decades later, this process is still frozen in places such as Moldova or Georgia. In Yugoslavia, although not quite “frozen”, the ethno-states born out of the war, known by the locals as BBR’s (Balkan Banana Republic) are barely functional, Bosnia in particular.

The Dayton agreement that ended the war sanctioned nationality over citizenship, with all citizens having to identify as either Bosniak, Croatian or Serb. Nowadays, no one can declare “Bosnian” in the Republic of Bosnia. As a result, poverty, widespread corruption and mass migration towards the EU, America and elsewhere have deprived Bosnia of a large percentage of their population. In 2019, the population of Bosnia was 3.3 million-in 1989, it was 4.5 million.

Grant: What was your inspiration for this game? Why did you feel drawn to the subject?

Javier: I’ve been interested in the Yugoslav wars since they happened (and in other conflicts of the post-Soviet space), and have designed a few games on these conflicts, and other earlier wars in the region (Yugoslavia ’91, Partizan, Balkans ’44). I have also travelled across the countries of the former Yugoslavia for many years and I have to say that I feel at home there.

There are not many simulations of this conflict (at least compared with other more shall we say “popular” conflicts). However, at least in this case, quality compensates in part for the lack of quantity. In recent times, we have the excellent Brotherhood and Unity, a card driven game of the Bosnian War, and more recently Operation Bøllebank, a truly groundbreaking design. Highly recommended.

Grant: What was your design goal with the game?

Javier: Civil Wars are so much more difficult to simulate because there are too many non-kinetic factors involved-these wars are fought by the population, not by regular militaries that can (more or less) limit the violence to the other regular forces. More so in a very complex situation such as Bosnia in 1992-95. The design goal was to show the politico-military dynamics of this conflict, and the logic behind these.

Grant: What type of research did you do to get the details correct? What one must read source would you recommend?

Javier: The best source in English (although difficult to find) is Balkan Battlegrounds, a highly detailed two-volume work on the Wars in former Yugoslavia, with very accurate maps and orders of battle. Incidentally, the foreword to this book was written by none other than David Isby, of SPI fame. Other interesting works on Bosnia include The Muslim-Croat Civil War in Central Bosnia by Charles R. Shrader.

Grant: What from the Bosnian War was most important to model?

Javier: Being a long conflict, with lots of factions involved (up to five), I had to keep it simple and put the focus on a few key elements. This is a rather obscure subject and the military history of the war is relatively unknown, so I tried to keep it simple using familiar mechanisms.

The most important factors to simulate were a.) the learning curve of the amateur armies, and b.) Western intervention in support of the various armies. The Bosniak and Croat armies begin with a low proficiency rating, which allows them to coordinate very few ground and support units. They had plenty of replacements, but no more than two can launch an attack against the same target. This can change thanks to lessons learned, and also via support received from other countries. The Serb army begins with a high proficiency rating because they got most of the cadres and professional staff of the former Yugoslav Army, but they can lose their proficiency rating due to Western intervention (attacks on command posts and communications degrade their ability to coordinate units and support elements).

As the war in Bosnia dragged on for years, the Western powers began to consider intervening and/or using the Croatian army as a proxy force that could break the stalemate and force the warring parts to sign a peace agreement. The NATO intervention track begins from no intervention to partial intervention (air strikes against artillery and command posts) to full intervention-the Bosnian-Croat player has more NATO air strikes, and the Croatian army can intervene.

Grant: How does the process of design change for a magazine wargame vs. a larger boxed game?

Javier: Like I said in earlier interviews, there are no differences from the point of view of the design. A magazine wargame is just like a boxed game minus the large box that, in many cases, only contain air. The advantage of a magazine game is that they can publish on relatively obscure subjects that an editor would be reluctant to publish in boxed format.

Grant: What is the scale of the game? How did you design the game around that scale?

Javier: Like its systemic cousin Nagorno Karabakh, Bosnia uses quarterly turns. The longer turns comes in handy to simulate the slowest pace of events. Units are brigade sized units, with 50 km hexes.

Grant: What different unit types does each side have access to?

Javier: It was an overwhelmingly infantry based war, because of the terrain features and also because of the general lack of heavy weaponry, in particular for the Bosniaks and Croats, not so for the Serbs. We have a mass of light infantry with a handful of mechanized, armored and Special Forces.

Most civil conflicts are “amateurs’ wars” and Bosnia was not an exception. At the beginning of the war, almost all professionals were in the VRS, the Army of the Bosnian Serb Republic. The other two sides, the Bosnian Government in particular, had to learn as they fought, a very difficult and costly situation. The average “divisions” of the various armies represent actually groups of brigades rather than divisions that can operate independently. In the Bosnian War, the term “brigade” could include anything from 3,000 to a few hundred troops, from elite units to local, part-time territorial militias, so a “brigade-level” order of battle would be impossible. Therefore, I grouped units into divisional-sized “Operational Groups” deployed by all combatants in the war. Each such “OG” had some 4,000 to 5,000 troops.

Grant: What is the anatomy of the counters?

Javier: Units have attack-defense-movement ratings, with NATO icons. SF forces (or “sabotage and recon” in the local parlance) have no attack or combat ratings. There are icons for artillery and air support markers. In general, most units have low movement ratings, even though we have quarterly turns. Low mobility ratings of average infantry simulate a number of things such as lack of suitable roads, the complex geography of the country (mountains and forested areas everywhere), or lack of motor transport. Also, some of these units represent local defense militias.

Grant: What is the general Sequence of Play? What type of experience did you want the Sequence of Play to invoke?

Javier: Being a two player game covering a situation pitting three or more armies the sequence of play requires random events to simulate things like the Croat-Muslim War of 1992-94. There is a random events phase, followed by reinforcements, then a Serb movement-combat phase followed by Bosnian-Croat movement-phase. The Bosnian-Croat units are generally controlled by the Government player, although the event Muslim-Croat War allows the Serb player to use the Croats to attack the Bosnians.

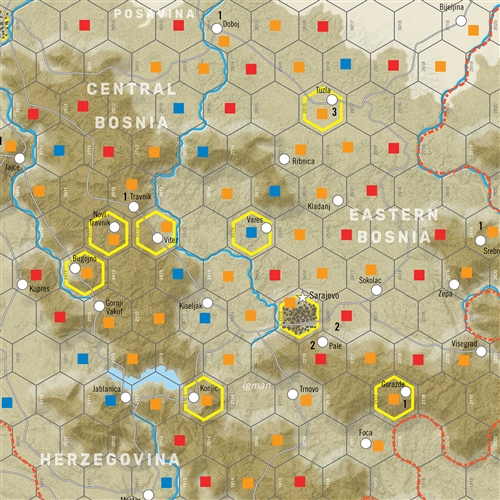

Grant: What area does the map cover?

Javier: The hex map covers all of Bosnia and surrounding countries at 50 km per hex, from Western Montenegro to south-central Croatia.

Grant: What strategic pinch points does the terrain create?

Javier: There are plenty. Bosnia is a heavily forested and rough country, with a very sparse road net. In 1992, Bosnia only had some 7,000 miles of asphalted roads, and many of them are cut into the sides of the abundant mountain ranges of the country, and therefore could not be detoured easily when blocked by an enemy force.

Grant: What are the majority population hexes and what purpose do they serve?

Javier: The map shows the physical but also the human geography as well, with majority Croat, Serb or Bosniak population hexes, at least as they were in 1992. Things, unfortunately, have changed, and all involved sides have blatantly ignored the agreements allowing the return of displaced persons to their towns and villages. Control (and/or cleansing) of these hexes is key to win the game.

This conflict had a military logic, even though the targets were not only geographic objectives, but the population itself. Forcing the other side to evacuate their population would deny them with important resources and force him to resettle and feed a large number of refugees. However, this also caused the contrary effect-many of the best Bosnian units were raised among refugees, who had no local territory to defend, further fueling the conflict.

Grant: What is the purpose of the Arms Factory symbols?

Javier: Given the arms embargo (that mostly affected, at least at the beginning, to the government side) there was a small number of smalls arms and ammunition factories which were key to keep on fighting. The loss of these factories would be crippling blows for the Bosnian war effort.

Grant: How does the game deal with ethnic cleansing? How did you handle this to be representative but not overly gruesome?

Javier: “Not overly gruesome” is perhaps a question that we should formulate for all wargames, not only the ones dealing with civil wars and ethnic cleansing. Perhaps we should remember that behind the sexy Panzer divisions racing across the steppes in 1941 came the Einsatzgruppen in charge of eliminating Jews, Gypsies and other “undesirables”. Or perhaps we should keep in mind that the Soviet Guards Armies advancing to the West were followed by NKVD detachments bent on eliminating the enemies of the state. Just to name an example, more than 7% of the total Estonian and 9% of the total Lithuanian population perished in the Soviet occupation of these countries in 1944-50. This figure doesn’t include people killed in 1940-44-only the victims of the “pacification” of these countries. No surprise that the Estonians, Latvians or Lithuanians are literally digging trenches as we speak.

In the East front we can design and play a game and ignore these factors. But in a civil war simulation we can’t ignore that. In Bosnian War, the population was a target, and I want players to face that fact. And it was a target not because some irrational “ancient hatred” that went back centuries. It was a target because of a rational decision of the actors, and also because the various peace plans envisioned the partition of the country along ethnic lines. Therefore it made sense to have territories “as ethnically pure” as possible to get a bigger portion. However perverse, there was logic in ethnic cleansing. Historian Alexander Watson (speaking about post WW I Eastern Europe), wrote that “the principle of national self determination raised competition between peoples to a winner-takes-all struggle of national survival, such change inevitably brought bloodshed.” This is valid for post WWI Europe, but also for Yugoslavia or the Caucasus.

I play wargames to learn, and to experience the challenge, or the thrill, of changing history. Or to face the same historical dilemmas. Likewise, I design games to teach a thing or two about a given conflict. But, to be honest, I feel uneasy by the word “fun” in a historical wargame.

Grant: What different random events are involved in the Random Events Phase?

Javier: As in several of my other designs, random events is a very useful mechanism that allow the design to simulate in a credible way a number of things – from diplomacy to internal conflicts to breakaway regions. Things outside of the scope of the players, or that can only influence the outcome if players achieve certain objectives.

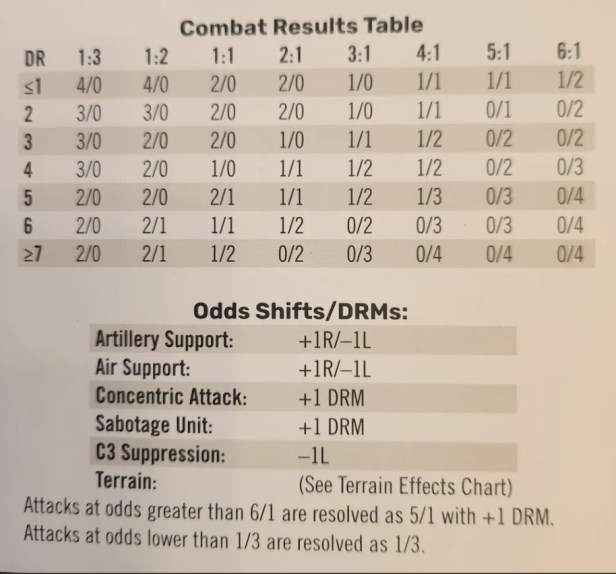

Grant: How does combat work?

Javier: It is odds based. The proficiency rating of the various armies determine how many units can participate in a given attack. Units performing advance after combat can also perform ethnic cleansing, so the mechanism is integrated into the military operations dynamic.

Grant: What is the makeup of the Combat Results Table? What unique odds are represented and why?

Javier: The CRT is rather bloody, in particular when attacking urban areas. The use of support elements is crucial to reduce casualties. This is an advantage to the Bosnian Army-over time, their replacement rate is much higher than the Serb one. However, the loss of Bosnian population territory can hurt their replacement rate.

Grant: How do Replacements and Withdrawals work?

Javier: The Bosnians had plenty of replacements (44% of total population were Muslims), but lacked firepower and trained cadres, while the Bosnian Serbs had better quality, more firepower and more professional leadership, so they could not easily replace big losses. Hence they were reluctant to engage in large urban battles, and contented themselves with besieging them to try to force the population to flee (as happened in Sarajevo). The Bosnio-Croatians had somewhat better firepower (they had the support of the Croatian Army) but even less replacements.

The number of replacements received by each side depends on the number of friendly population hexes controlled. Some withdrawals are handled via random events, representing the upgrade and retraining of units.

Grant: How are Artillery, Air and Naval Support handled?

Javier: These are handled as support markers that can be used to enhance defense or combat. The proficiency level of the various armies determine how many can be used in a single combat. The better proficiency, the more support counters can be used in a single combat.

Grant: How do players win the game?

Javier: By taking geographic objectives, and also by destabilizing the other entities flooding their remaining territory with refugees.

Grant: What type of an experience does the game create?

Javier: Players can learn a thing or two about a conflict. In this case, about the Bosnian War in particular and about the breakup of Yugoslavia in general. Game wise, it is a clash of quantity versus quality, with one side slowly gaining quality against another side that is slowly losing it. Players will learn that the only real war is the total, complete and deliberate annihilation of your enemies, civilians (and above all civilians) included. Everything else is but a modern version of the Lace Wars of the 18th century.

Grant: What are you most pleased about with the design?

Javier: I think that the game does a good job (without too many rules) at modeling what happened in Bosnia, at least from a military point of view.

Grant: What has been the response of playtesters?

Javier: Playtesters were intrigued by the system. One of them had to “suspend his disbelief” to play the ethnic cleansing, but, as he said “it was a vile component of the war and has to be addressed in some way”. In his testing the Serbians by far did the majority of the cleansing, even though the experience of other players may differ. Another remarked that “I felt a bit uncomfortable mentioning ‘placing an ethnic cleansing counter’ on a hex. That may be part of the designer’s goal of the game, and if so, a hearty well-done to them for that.” If so, then I feel that my job is done here.

Overall, despite of this aspect of the war, most playtesters had an interesting experience playing this simulation. They struggled to adapt to the realities of this war-to think in terms of population centers, not frontlines or defensive terrain. They had to disperse, not concentrate forces, at least in the early stages of the war.

Grant: What other designs are you working on?

Javier: I am about to publish Ukraine Battles 2014-15 for S&T, Finland ’44 and Path to Victory: the Middle East in 1941 for World at War, and Red Partisans for Paper Wars. I’m currently reworking Aragon ’38 for SNAFU Design Team. Aragon ’38 is an adaptation of the Santander ’37 System to a more mobile situation such as the Aragon campaign of 1938. I’m also working on The Rif War for S&T, a simulation of the 1925-26 phase of the Rif War between the Republic of Rif and a French-Spanish alliance, a very interesting conflict. In a sense, the Republic of Rif was a forerunner of more modern national liberation movements such as Algeria or Vietnam in the 1950’s.

Thanks for your time Javier in answering our questions as I know you are a busy man and always have lots of interesting gaming subjects on your design table. I am very interested in this one and appreciate your approach, especially with dealing with the more controversial and difficult portions of the conflict such as targeting population and ethnic cleansing. I need to get a copy soon to give this one a try!

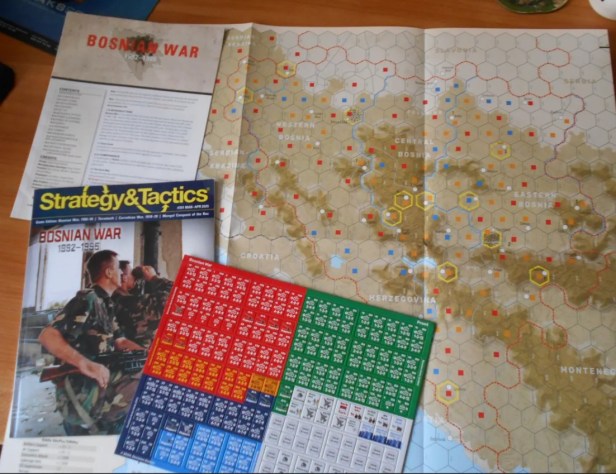

If you are interested in Bosnian War 1992-1995 from Strategy & Tactics Magazine #351, you can order a copy for $49.99 from the Strategy & Tactics Press website at the following link: https://shop.strategyandtacticspress.com/ProductDetails.asp?ProductCode=ST351

-Grant

Well, like some of the play testers i would surely be uncomfortable with “placing an ethnic cleansing counter”. The problem here is that you can’t avoid the civil part in this conflict, it’s not purely a regular army engagement and the design must take it into account.

It’s perhaps less direct as a game like “this war of mine”, that i never imagined to play but still a delicate topic. Not for me and moreover when we have such a large number of purely strategic/tactical games.. Which some are still on top of the shelf of shame 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person