As you know, I do love me a good Card Driven Game. I love the mechanic because it allows for the designer to keep a game going while using cards that incorporate special rules that fit a historical situation but also to be able to use bits of the history itself to teach the players about the topic. A few months ago, I caught wind that The Dietz Foundation was working with a new designer named Yoni Goldstein on his first game called Chicago ’68 for a summer Kickstarter campaign. Chicago ’68 deals with the Democratic National Convention riots of 1968 in Chicago and sees players taking on the role of either the Establishment or the Demonstrators in a fast-paced game of street battles and political maneuvers. I reached out to Yoni and he was more than willing to discuss the game with me and also work on a series of Event Card spoiler posts in a run up to the Kickstarter campaign that is set to launch on August 6th.

If you are interested in Chicago ’68, you can check out the Kickstarter preview page at the following link: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/dietzfoundation/chicago-68?ref=discovery

Grant: Welcome to the blog and thank you for accepting our invite to do this interview. First off Yoni please tell us a little about yourself. What are your hobbies? What’s your day job?

Yoni: First of all, thank you for the invitation!

In my other life, I’m a full time filmmaker and cinematographer. I work primarily in the world of arthouse, experimental, and nonfiction documentary – typically as a director of photography. My work circulates in festivals and museum / gallery exhibitions, but my documentary films seem to have a deeper reach. The most recent project I shot was titled Demon Mineral, an award winning film about the baleful history of uranium mining in the Navajo Nation, which was shot largely in infrared black and white.

As for hobbies that don’t include games or films, I’m an avid reader of poetry, theory, and literature. I really enjoy reading Byung Chul Han (I particularly love his meditations in Shanzhai – Deconstruction in Chinese) and adore Anne Carson’s poetry and essays (Glass, Irony & God is a favorite).

Grant: What motivated you to break into game design? What have you enjoyed most about the experience thus far?

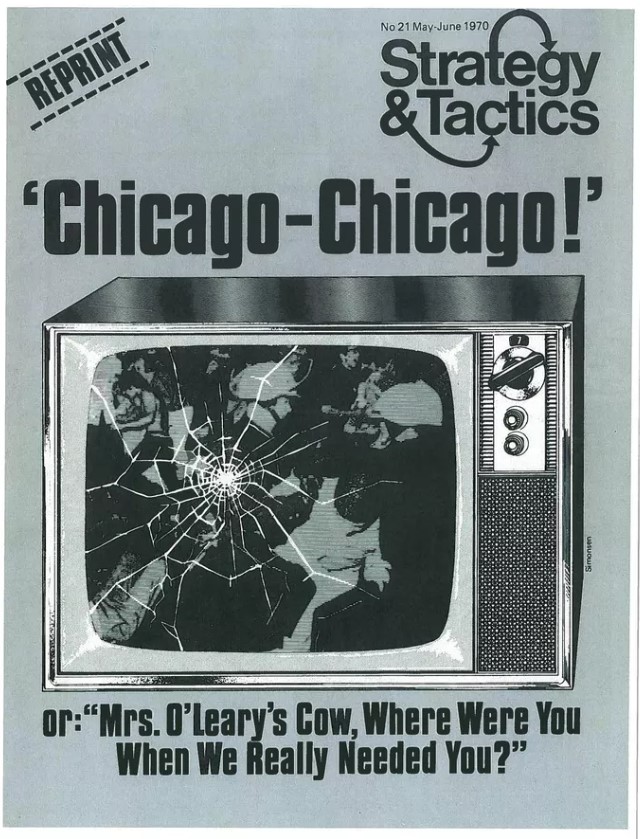

Yoni: I suppose that like many new designers of my generation, I really leaned into designing during lockdown. With a bit of time on my hands I started tinkering and iterating on existing games. One of them was Jim Dunnigan’s Chicago-Chicago! Or: Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow, Where Were You When We Really Needed You? – a cheeky, near-contemporaneous take on the convention riots as a war game. At the time, I was motivated by a desire to play more games about social movements, underrepresented conflicts, and local Chicago history. Dunnigan’s game felt like an exciting thought piece (almost like live reportage) but I wanted more from the model. I was starting to consider the way that street protests seem to be a form of radical improvisational theater. This was especially germane at the time as the George Floyd / BLM protests flooded into my neighborhood in Chicago (which happened to be where our beleaguered Mayor resided).

It was at this point that Chicago ‘68 came into being. Fortunately my brother, Ronen Goldstein, has been toying with his own designs and taught me how to develop games on TTS and the Game Crafter. From there, I found my glee in the intellectual challenges of research and ideation, and of course, the tactical thinking that this emergent, anything-goes match up produced (it’s especially fun when accented by sibling rivalry). In short, I found myself designing the game I actually wanted to play.

Grant: What is the focus of your upcoming game Chicago ‘68?

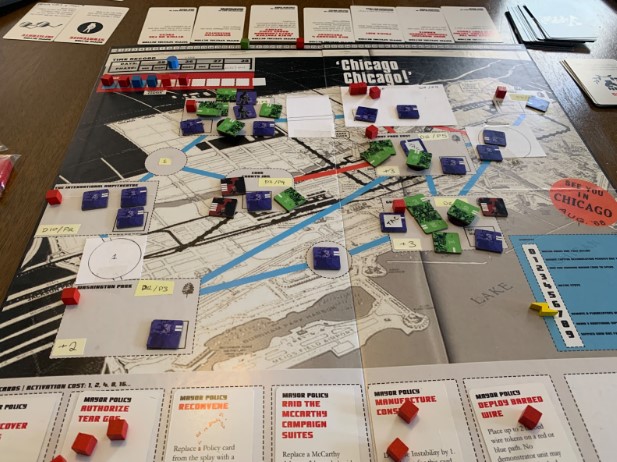

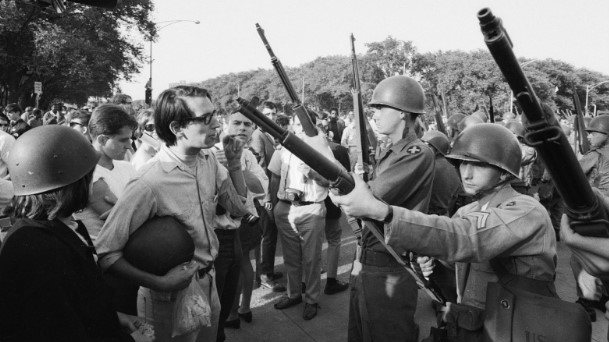

Yoni: This is a game about the riots during the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, set against the social upheavals of America in the sixties. After the Summer of Love, the Summer of Tear Gas. On one side: the Youth International Party (aka The Yippies) and the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam (aka the MOBE), on the other: Mayor Daley, the Chicago Police Department and the National Guard. The game unfolds over the course of three days during the Democratic National Convention – from the 26th to the 29th of August, culminating in the nomination of a presidential candidate. There are two victory conditions: one is to gain the most media exposure favorable to your side and the other is to influence the delegate vote and bolster your political aims. The Demonstrators may pivot between these two objectives while the Establishment, although more powerful, must fight and win on both fronts.

Chicago ‘68 supports 1 – 4+ players, featuring asymmetrical card actions and tableau activation. Typical duration of play is about 45 minutes per player.

Grant: Why was this a subject that drew your interest?

Yoni: Chicago is my adopted hometown. From the Haymarket anarchists, to Milton Friedman and the Chicago boys, to Chairman Hampton and the Panthers, this city is one of those places that expresses the complexities of world history. Researching the material for this game has been my way of excavating meaning out of the sidewalks, avenues, and parks where I spend my days. It has brought me closer to the place where I live.

Grant: What is your design goal with the game?

Yoni: My aim with Chicago ‘68 is to create a game that opens up a space where we can link ourselves to the past. In this way, it’s more akin to a folk song than a strict historical simulation. While all the events depicted in the game happened in the past, the players are challenged to inhabit their roles as if history does not point to an inevitable outcome. After all, a “riot” comprises a million points of conflict, but when a player resolves a conflict card it signifies an action that is “historical” – i.e. an event that gloms onto our collective memory and becomes something worth remembering through music, board games, or movies.

Of course this is a competitive game and as such is grounded in the playful joy of outmaneuvering your opponent. Perhaps you’ve just dominated a street battle or cleverly chained card effects in a “big move.” My goal is to place this joy in the foreground. But in the background is this larger vision of the shared historical narrative, which neither side was ultimately able to control.

Grant: What sources did you consult to get the historical details correct?

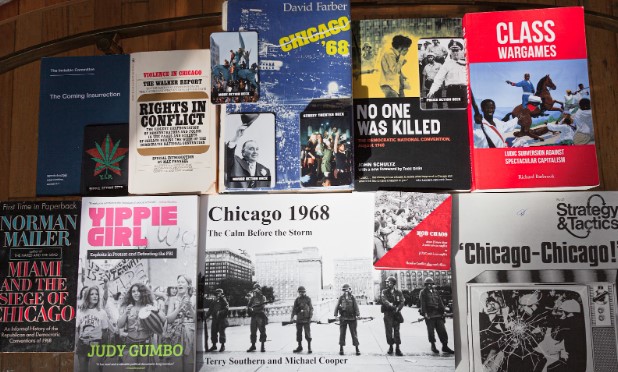

Yoni: The guiding document for the game is Rights in Conflict: Convention Week in Chicago, 8/25-29/1968 by Daniel Walker, director of the Chicago Study Team, appointed by the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence. “The Walker Report”, as it is commonly known, collected over 20,000 pages of statements from 3,437 eyewitnesses and participants, 180 hours of film, and over 12,000 still photographs. Its pages describe firsthand accounts of the violent acts committed “far in excess of the requisite force for crowd dispersal or arrest.” In dispassionate terms it describes what “can only be called a police riot.”

Also relied upon was the Strategy of Confrontation report by the Chicago Department of Law. This was the city administration’s response to the Walker Report, which claims to have uncovered plots to “assassinate Senator Eugene McCarthy, Vice President Hubert Humphrey, Mayor Richard J. Daley and other political and civic leaders” and the manufacture of “primitive but effective missiles” such as “golf balls with nails impaled therein, Potatoes with razors hidden inside, [and] live black widow spiders.” Needless to say, the veracity of these claims do not age well.

Other reading material include Chicago ‘68 by David Farber, The Siege of Chicago by Norman Mailer, Yippie Girl by Judy Gumbo, No One Was Killed: Documentation and Meditation: Convention Week, Chicago, August 1968 by John Schultz.

This game is deeply indebted to the works of local historian Dean Blobaum, who created a comprehensive online chronology at chicago68.com. I had the pleasure of demoing an earlier prototype to Dean, who helped me define some of the counterfactual possibilities as well as identify a number of supporting texts on Chicago’s south side and Black participation in the movement.

I’m also grateful for support from Nick Proctor, whose own work on ‘68 in the Reacting Consortium has been invaluable in sharpening the historical details.

Lastly, there are some fantastic films that are key to the “cinematic” vibe of the game. The first is Medium Cool by Haskell Wexler, a film that I liken to Dunnigan’s Chicago-Chicago! as it combines historical construction with reportage from the DNC. The second is Jean Genet in Chicago, a short documentary by my former film professor, Frederic Moffet. If you ask me if I have any hero in this whole story, it’s that sweet softboi radical, Jean Genet.

Grant: What social dilemmas and questions do you hope to approach and even answer with the design?

Yoni: I wanted to design a game that is neither neutral nor biased. The demonstrators were right about the war but they couldn’t find a way to channel their mobilizations into collective power. The opposing side, likewise, could only act within preexisting power structures. As Tom Hayden would write, “The rules of the convention, like the rules of the game everywhere, will be changed to suit the makers of the rules. Where the rules neither command respect nor fool people, military force will be applied to enforce the rules. The presence of thousands of police and army troops in Chicago, ringing the convention amphitheatre, will show the increasing bankruptcy, the reliance on violence instead of persuasion and consensus, of American rulers. Instead of achieving Humphrey’s dream of exporting the Great Society to Asia, America will have brought Vietnam home.”

I’m not one of those people who thinks about a “generation” as a coherent category across society. I’m certainly not given to romanticize the hippies as a political force, either. However, there are certain moments that are so formative they create a sense of generational consciousness. The DNC riots in Chicago signaled one of these generational moments (just as the alienation that most young people experience in the face of today’s party politics will define their position in tomorrow’s society). And yet what the New Left struggled for – the long hard work of the fundamental transformation of society – was covered over by expressions of individual freedom.

Grant: The game uses cards as an action menu. Why is this the perfect vehicle for this history?

Yoni: The cards in your hand represent proposals for action. Each turn is an encounter between various councils or committees, sometimes this is a handful of young radical “marshals” on the street, sometimes a room full of city administrators and high ranking officials. You, as a player, enact the collective will of these historical subjects. What is depicted in these cards is not inclusive of everything that happened, rather it’s the actions that produce history.

You are cornered, overwhelmed and outnumbered. Do you clash as a mob or abandon the streets and pivot toward electoral reform? Negotiate with the protestors and lower unrest or arm yourselves with teargas and armored jeeps? Using cards that can only be activated once per round is a tactile way to whittle down the player’s decision space and to emphasize the sense of crisis and urgency. The events are shuffled into separate decks so what is left in your view is the immediate problem and finding the means to resolve it. And yet, taken as a whole, these card effects aggregate to form a wider, almost cinematic, perspective. When the dust settles you acquire a view on the state of affairs from the historian’s perch: thousands of injuries and arrests; a weak presidential candidate; collapse of civil order; a televised catastrophe. Or maybe you found a way around all this?

Grant: What other card based games inspired your design?

Yoni: I’m a newcomer to the scene so my exposure to war games and CDG’s in general is relatively anachronistic. I try to play anything that catches my eye, especially games that grapple with social movements and leftist history. One game that stands out for me is Fred Serval’s Red Flag Over Paris. I think it’s a very astute take on the multiple domains of struggle that emerge between a militant insurgency and a much more dominant power. I very much appreciate how the theater of war in this design is inclusive of political and media struggles alongside military operations. This asymmetry in expressions of power through different means of warfare is also carried over in A Gest of Robin Hood, which came out before our design for Chicago ‘68 but is still very much of a similar vein.

Grant: What different types of cards are included in the design?

Yoni: Each side has two action decks – the Leadership (or vanguard) Deck and a Rank-and-File Deck. They will play 3 cards from each deck per round and have the ability to add cards throughout the game. I’ll explain the relationship between the Leadership Deck and the Policy / Street Theater Card tableaux below, but broadly speaking these cards allow the players to manage the board state from a more removed perspective. The Rank-and-File Deck, representing the MOBE and the Chicago Police Department, allows for more kinetic action through conflict cards and larger scale movement. Lastly, the Mob Chaos Deck is a special event system that is triggered primarily through conflict. Conflict in this game is deterministic, however, when 5 or more units are in conflict or when a special police unit like the Tactical Force, is deployed, a Mob Chaos is resolved according to either the daytime or nighttime effect (which is determined by the round order). Typically, daytime effects favor the Demonstrator while nighttime effects favor the Police.

Grant: What is the purpose of the Street Theater Deck? What is the name derived from?

Yoni: The Yippies in particular believed in the spectacle of public turmoil as a revolutionary platform. They understood that they were powerless against Police actions and the National Guard and so performed symbolic resistance by “soaking up” the violence for all the world to see. As Abbey Hoffman would observe in situ, this is theater, deadly theater, and both sides are playing their roles. Hoffman would compare the Yippie struggles against the Chicago establishment to the American colonial revolt against the British Empire.

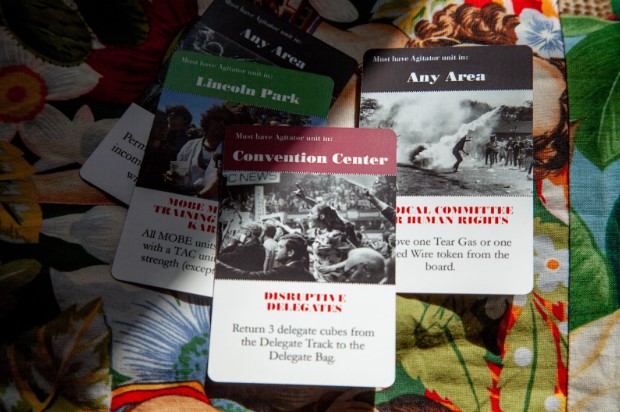

In the game, when the Yippies agitate they add cards to the Street Theater splay. Each card represents a hypothetical engagement with a particular city area. It may be an illegal concert by Phil Ochs in the middle of the main thoroughfare. Or coalition building on the south side, leading an ohm chant with Allen Ginsberg, or fighting for the Peace Plank on the Convention floor. Each Street Theater Card is grouped into one City Area with an effect that tells the history of that location (e.g. the violent confrontations in Michigan Avenue, the political maneuvers in the Convention Hall, etc.). To trigger these events, the Demonstrators must position their special Agitator pieces in the required location. They act as mini-objectives for the players and can be chained together for widespread mischief making, political interference, and guerilla tactics.

But peppered throughout the deck are also counterrevolutionary cards, representing internal tensions, government moles, and other obstacles to effective organizing. These cards deplete and remove Agitators from the Demonstrator ranks.

Grant: What is the Leadership Deck?

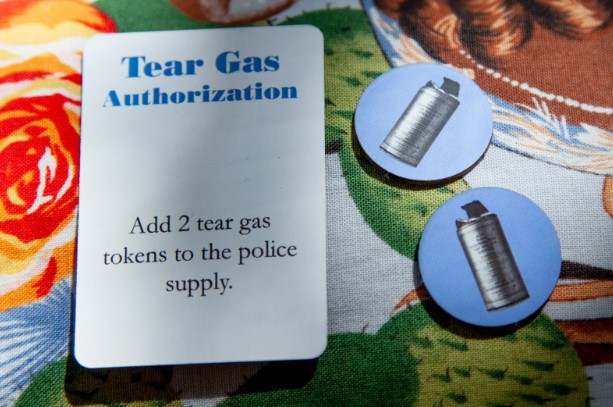

Yoni: For the Establishment, the Leadership Deck represents the command structure headed by Mayor Richard Daley, city administrators, and the Democratic party bosses (with LBJ making phone calls behind the scenes). The Mayor et al may spend political and financial capital on activating various policies which will contain and prevent the demonstrators from disrupting the convention. Other actions in this deck will allow for interference in the delegate vote, greasing palms, and equipping the police force with tear gas and barbed wire.

The Demonstrators, on the other hand, have a loose vanguard of Yippie Agitators who may call for rallies, lead other Demonstrators, and – most importantly – “Agitate” and thereby populate the Street Theater splay. Compared to the Rank-and-File Decks, these actions are much more oriented toward organizing and strategizing than direct street conflict.

Grant: Can you show us a few examples of cards and explain how they work?

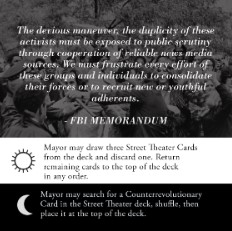

Yoni: This is a Mob Chaos Card. Each Mob Chaos event features an excerpt from a primary source document, typically a firsthand account of the scene. This one, however, is from an FBI memo issued by J. Edgar Hoover prior to the Convention. The memo concludes by stating the aims of COINTELPRO: “The organizations and activists who spout revolution and unlawfully challenge society to obtain their demands must not only be contained, but must be neutralized. Law and order is mandatory for any civilized society to survive.”

The card effect is also unusual because it allows the Establishment to interact with the Street Theater Deck. The night event is especially disruptive to the Demonstrators as it will plant a Counterrevolutionary in the next Agitate action.

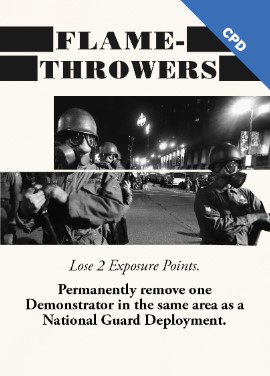

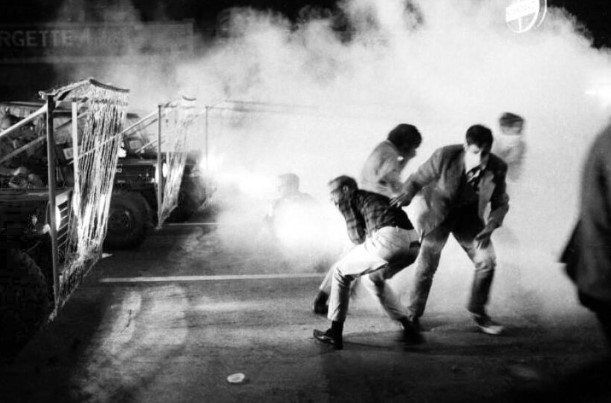

The “Flamethrowers” Card is a special Action Card that the Mayor can add to the Police Deck through the policy splay. During the convention, National Guardsmen were equipped with converted military grade flamethrowers (“CA-3 back-pack sprayers”) to dispense tear gas at close range. One witness recalls the use of these weapons near the downtown bridges over the Chicago River: “As the crowd swelled, it surged periodically towards the Guard line, sometimes yelling, ‘Freedom, freedom.’ A Guardsman stepped in front [of the Guard line] and walked the width of the bridge laying down a stream of tear gas. The wind was then from the northeast and the gas was generally blown back into the Guard lines and southwest toward the Hilton…”

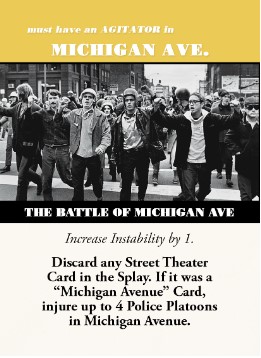

Lastly, this is a powerful Street Theater Card that demands careful timing to trigger effectively. It depicts the so-called “Battle of Michigan Avenue” on August 28th. In the game, I allow the possibility that some demonstrators were capable of fighting back. However, what typically occurs next is that the Police player takes advantage of Agitator presence to mass arrest or tear gas in Michigan Avenue.

Of all the instances of street violence, this event got the most coverage because it happened within view of the Hilton Hotel. The Walker Report quotes CBS engineer Fred Turner, viewing the events from his vantage point on the fifth floor:

“Now they’re moving in, the cops are moving and they are really belting these characters. They’re grabbing them, sticks are flailing. People are laying on the ground … Cops are just belting them; cops are just laying it in. There’s piles of bodies on the street. There’s no question about it. You can hear the screams, and there’s a guy they’re just dragging along the street and they don’t care. I don’t think … I don’t know if he’s alive or dead. Holy Jesus, look at him. Five of them are belting him, really, oh, this man will never get up.”

Grant: What role does the Area Control mechanic have in the design?

Yoni: At the end of each round (of which there are 5), there is a quick “Meet the Press” event where each City Area is assessed for control. Each cube on the board is either a MOBE or Police Platoon with an organizational strength value – 1 for the little cubes and 2 for the big cubes. Here, Strength represents that unit’s capacity to resolve conflict in their favor (whether nonviolently or through other means). If one side has greater strength than the other, they gain 1 exposure point. This represents a certain control of the media narrative (e.g. “the Police are effectively policing the protestors in Grant Park”). At first, with many of its officers spread out across the city, the Establishment is typically in a comfortable lead when they meet the press. But as more and more demonstrators flock to the city, it becomes a tenuous grip.

Control comes into effect in other ways as well. With critical mass in multiple areas, the Yippies are able to simultaneously call for multiple rallies across the map. This will also raise their exposure and flood the streets with supporters. Even without control, simple presence will choke the Mayor’s capital income which is critical for policy making (i.e. activating the policy supply during the leadership phase).

Grant: What is the layout of the board and the purpose of the various City Areas?

Yoni: Each space on the board where a unit can be placed is a “City Area.” This includes historically significant sites like the Convention Hall, the Hilton Hotel (where many of the delegates and politicians were accommodated), and Michigan Avenue (the main commercial artery in downtown Chicago). Other City Areas include the parks, where the demonstrators initially gathered, and “transit areas” which add interstitial spaces representing geographical distances between locations. Each City Area has an Exposure Value representing the shifting dynamics of news media coverage – i.e. Demonstrators who stir things up on the Convention floor will gain more Exposure in their favor than the police officers who have to arrest them. Inversely, the Police are incentivized to enforce law and order in the Parks, where they are more likely to gain favorable Exposure. The main City Areas (i.e. not the transit areas or Cook County Jail) will also provide capital to the Mayor, assuming that the police are successful at clearing out any Demonstrators before the round ends.

Grant: What different factions are represented?

Yoni: As mentioned above, there are four playable decks, two per side. In a two player game, each player plays from both the Rank-and-File and Leadership Decks. In a three or four player game, these decks are divided into a 2v1 or 2v2 match up. On the Demonstrators side we have the Yippies and the MOBE; on the Establishment side, The Mayor and the Chicago Police Department.

The Demonstrators

The “Revolutionary Action-theater” of the Youth International Party (whose members were commonly called “Yippies”) expressed an irreverent, artistic and countercultural resistance against what they saw as the US war machine. In this game, the Yippies are a strategic counterpoint to the Mayor. They activate their Agitators, a unique vanguard unit capable of rallying and leading other demonstrators and generating a dynamic tableau of Street Theater effects.

The National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam (the MOBE), along with other antiwar and civil rights groups, represent the protesting force in the street. In “Democracy is in the Streets,” Tom Hayden, one of the Mobilization coordinators, declared: “We are coming to Chicago to vomit on the ‘politics of joy,’ to expose the secret decisions, upset the night club orgies, and face the Democratic Party with its illegitimacy and criminality. American conventions and elections are designed to renew the participation of our people in the ‘democratic political process.’ But in 1968 the game is up.”

The Establishment

“The Mayor” represents the Chicago party bosses, Richard J. Daley, the city administrators, and the Democratic National Committee. They do not have any unit presence on the board. Rather, they control the political progress of the Establishment and support / fund special Police actions through a powerful splay of policies and mandates.

The Chicago Police Department is the enforcement arm of the Establishment. They play the critical role of containing, arresting, and dispersing demonstrators from high value areas. Players must maximize their ability to gain exposure through successful police sweeps, effectively positioning their TAC Forces for tear gas deployment, and placing barbed wire to ensnare a highly agile adversary.

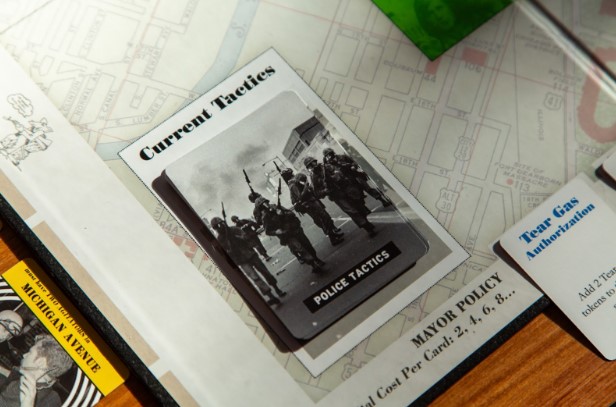

Grant: How do the Police use Tactics Cards?

Yoni: “Tactics” is a small deck of 6 unique abilities that the Police may activate once during their turn. If timed right, these cards can enhance the overall Police strategy against the Yippie’s Street Theater effects. Only one Tactics Card may be in effect at a time, but the Mayor may spend an action to shift Tactics during the leadership phase. Some of the Tactics include the ability to dismantle the Demonstrators’ rally flags (their recruitment points), to raid the opposition candidate’s suites and thereby remove a pledged delegate, or to utilize Mob payoffs to benefit from raising instability.

Grant: What roles do things like tear gas and the National Guard play?

Yoni: In pure game terms, the National Guard Deployment is a strength modifier for the Police. It nearly guarantees area control and can effectively deny most clashes as long as a Police Platoon is also in the area. However it is not a unit that the Police can simply command to move or arrest. Instead, it responds to a redeployment order in the leadership phase and can be particularly fearsome if the Mayor mandates certain policies. For the most part though, the National Guard is highly disciplined, restrained, and defensive.

Grant: How are protesters put into the Cook County Jail? How are they released?

Yoni: Conflict resolution is determined by the faction that initiates it. When the Demonstrators clash, they will all confront a single Police Platoon with a lower strength value. That Platoon is injured (physically or morally) and placed off the map. The Police, on the other hand, have two conflict cards – “Advance” and “Mass Arrest.” These actions will place up to 4 demonstrators of lower combined strength in the Cook County Jail area. Cook County Jail is a City Area that is not adjacent to any other area, naturally meaning that Demonstrators may not move in and out freely (although creative players may realize they can agitate and rally within jail as well). At the beginning of every round, the Demonstrators may bail out any of their units to any Park at the cost of 1 capital cube per unit. This will enlarge the municipal budget, handing over critical resources the Mayor relies on to activate the policy splay.

Grant: How is end of round voting handled?

Yoni: In 1968, the center left and anti-war vote was split between Robert Kennedy and Eugene McCarthy. When RFK was assassinated, the delegate count stood at Humphrey 561.5, Kennedy 393.5, McCarthy 258. Kennedy’s murder left his delegates uncommitted.

In the game, I represent this with the cube distribution in the “Delegate Bag”. At the end of each round, a delegate cube is pulled blindly. Blue cubes represent delegates committing their vote to the presumptive Establishment nominee, Vice President Hubert Humphrey. Red Cubes represent commitment to Eugene McCarthy, the progressive dove. The Establishment cannot win without a majority of Humphrey delegates on the track at the end of the game. “Lucky” for them, they’ve already done the dirty work of stacking the bag in their favor (the delegate bag has 8 blue cubes and 4 red cubes at setup). After the fifth round, any empty spaces remaining on the delegate track are filled and victory is assessed.

Grant: How can players affect this vote?

Yoni: The Establishment may always leverage its capital to “work the machine” and ensure that the “correct” candidate is nominated, bypassing the bag pull for that round altogether. Not only does this have a resource cost however, it is also quite expensive when the action economy permits only three Leadership Cards per round.

From the Demonstrators’ perspective, the delegate process may seem entirely out of their hands … at first. But if they can manage to infiltrate the Convention Hall with the right Street Theater Cards at the ready, they can also sway delegates, persuade them to defect, and wreak havoc on politics as usual.

Grant: How is victory achieved?

Yoni: Victory is measured in two domains: the political as expressed in the Delegate Track (and described above) and the Exposure Track. The latter is a tug of war between two poles, with the news media rushing to file reports on events on the ground. Exposure is primarily gained whenever conflict is resolved in favor of one side or another, or when the Yippies mobilize a crowd with the Rally action. While the Establishment has the superior firepower in both realms, it must split its effort to win on both fronts simultaneously. Meanwhile, the demonstrators may freely swing from one victory requirement to the other – they only need to meet the conditions for either the delegate or the exposure objective to win the game outright. In the rare case that the Demonstrators win on both fronts they have achieved a decisive victory that transcends the historical narrative.

Grant: What are you most pleased about with the outcome of the design?

Yoni: If I had to narrow it down, the one thing that most pleases me about the design is how it continues to yield totally new and unexpected game states. Even now, after hundreds of plays, a unique strategy will emerge through the combinatorial possibilities between the various event decks / card effects. In fact, you will only see about 50-75% of all three randomized decks (the Mayor’s Policy Deck, the Street Theater Deck, and the Mob Chaos Deck) in any game. Order of operations matters in the way these cards interplay as well. One card effect may trigger multiple cards in your splay. So even though you will start with the same asymmetric menus of actions for each side, you will never play the same game twice.

Grant: What has been the feedback of your playtesters?

Yoni: I have to say that as a designer, watching players engage with Chicago ‘68 is a nail biting experience. There is a lot of agony and tension, emotional highs and lows, in the arc of this game. I have to watch (and hold my tongue) as at least one player will paint themselves into a corner of certain defeat until – inevitably – a slim, precarious path to victory opens. Will they make it through? Are they leaving it all to a single delegate pull at the end?? Gasp.

We’ve been collecting play testing data for about four years now, with various play counts over hundreds of hours. Feedback has been very positive and incredibly helpful for late development. Ultimately though, simply observing gameplay in person has been the most revelatory. Players’ ideological tendencies come to the surface – I’ve watched silently as the Demonstrators refused to engage in violent action until the last round, pushed into the Convention Hall and facing down a very aggressive Police player (and winning!). I’ve seen the Establishment rush to deploy every Police platoon to the man, crack some skulls, and then adjourn the convention altogether.

Grant: What other designs are you currently working on?

Yoni: My next game will be about the Luddite movement at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. It is a cooperative game where players organize raiding parties to smash machines and assassinate manufacturers. At the core of the game is a collective card engine that must be hastily constructed before the Regency cracks down on your secret society of saboteurs.

Thank you for your time in answering our questions Yoni! I am very much interested in this game and its efforts to tell this story. While this is not a traditional wargame, in my opinion it certainly merits a serious look from wargamers who are interested in CDG’s and that are interested in seeing these type of non-traditional historical subjects represented. I really like that it appears to use some very interesting tactics and strategies to tell this story about the social upheaval and turbulence of the late 1960’s and I am very much intrigued by it.

As mentioned above, we are also going to be hosting a series of Event Card Spoilers for the game over the next month or so in a run up to the Kickstarter launch in early August.

-Grant