I have read several War Diary Magazine issues over the past couple of years and have also seen that they have published several games including GUADALCANAL: The Battle for Henderson Field, 1942-1943 and 1914 DELUXE: Hell Unleashed. Roy Matheson puts out a quality publication but these games are also pretty damn good looking. Recently, they released a new Ancients wargame called Blade & Bow: The Ancient World at War designed by Mike Nagel. We reached out to Mike to get some inside information on the design.

Grant: I know you specialize in tactical level games. Why are you drawn to this subject over others?

Mike: I’m more drawn to tactical level games mostly due to their narrative ability. The closer a player gets to the shoes or boots or sandals of the combatants, the more visceral the experience. I can more easily identify with what’s going on during the battle than when pushing divisions, corps, or armies around.

Grant: How do you believe your approach to design works well in the tactical genre?

Mike: I don’t believe that my approach to design really impacts the genre or vice-versa. I think my professional career in application development and user experience pretty much defines how I go about getting a design out of my fevered brain and onto the table. You start by defining the goals of the design and then drive toward those, refining as you go along. This may involve going a lot further than necessary with regards to physical design (since a professional graphic artist will likely redo all the components anyway), but I believe that this is critical toward ensuring that the final design meets all the pre-established goals.

Grant: What is the focus of your upcoming game Blade & Bow?

Mike: Blade & Bow, which is already available from War Diary Publications, is about the evolution of ancient combat, beginning with the introduction of the Greek hoplite formation through the Roman maniples and cohorts. I hope to cover this through a series of quad games that cover different points along this evolutionary path. The first volume covers the Persian incursion into the Greek peninsula, through the battles of Marathon, Thermopylae, Plataea, and Mycale. These illustrate the effectiveness of the Greek hoplite formations against the masses of Persians and less organized allied formations. The next volume gets into the post-Peloponnesian War period, whose “star” battle is Leuctra, where Epaminondas determined that more is better, influencing the development of the Macedonian phalanx. From there it’s likely on to the Macedonians and then the Romans. That’s the plan anyway.

Grant: What was your inspiration for the name? What do you want it to convey to players?

Mike: I am really bad at picking titles for games. Someone suggested (after the fact, of course) that it should be called “Spear and Bow” or something like that, but I like the alliteration. I want the title to convey the simplicity and ferocity of ancient combat. I thought of going with “Sword and Sandal” as an homage to the great ancient battle films of the 1950’s and 60’s, but the reference might be a little too vague. “Blade and Bow” works for me.

Grant: What is your stated design goal for the project and who is your design audience?

Mike: My goal has been to create a system that provides a feel for ancient combat while stressing the evolution of infantry tactics during that period. Why was the hoplite formation so successful and if it was so successful, how was it superseded by other formations? I think the main design audience for this game (or any of my designs) is mostly me. I’m posing the question and then trying to answer it through the simulation I’m creating. It’s all fine and well to read about the subject matter in a book, which is, of course, necessary for research purposes. But actually putting theory into practice, short of slapping on armor and going at it with a hundred of your closest friends, provides a better level of understanding. I also design games that I would want to play and I hope that there are like-minded players out there who would benefit from the shared experience.

Grant: How have you shown and demonstrated the evolution of infantry combat from the Greeks to the Romans?

Mike: This is done through a couple of mechanics. The first is distinguishing different types of formations and how they’re deployed. These are light (disorganized masses of weakly armored troops without a clear formation), medium (organized lines of lightly armed and armored troops), and heavy (large numbers of troops in a tightly massed formation). These latter are further distinguished by formations that are dense (soldiers are fixed in place within the formation) or flexible (soldiers may move around within the formation). Further, heavy units are provided a “ranks” marker that indicates how deep the formation is. A Greek or Spartan hoplite would be a heavy, dense formation with one or two ranks. A Macedonian phalanx might have four or more ranks. A Roman maniple or cohort would have two extra ranks, but is flexible. This is where the second main mechanic comes into play, which is how units absorb damage. Generally, a first hit disrupts (flips) a unit, a second hit causes a unit to recoil, and a third hit causes a unit to rout. Dense units, however, absorb damage by peeling off ranks before they rout, while flexible units ignore hits up to their rank count before losing any. This difference distinguishes the pure mass of soldiers used in hoplite and phalanx formations from cohorts and maniples that were trained to morph “in situ” to allow the Roman formations to remain fresher over a longer period.

Grant: How does the game use cards?

Mike: Cards are used in several ways. First, they provide events that can be played to add bonuses to movement, combat, or otherwise feed the narrative of the battle. Secondly, they can be used to provide morale benefits to troops attempting to engage in melee (which is not automatic, unless a leader is present). Thirdly, cards provide a random number of “impulses” a side has during an activation, based upon the quality of an army’s commander. With regard to this third use, I was going to use special dice to determine the impulses, but the game already uses a lot of dice for combat, so the cards avoid this necessity nicely.

Grant: What is the anatomy of these cards? Can you show us a few examples and discuss their use?

Mike: The text in the middle of the card is the event. Each event indicates when an event can be played and what its effects might be. The number at the upper left is the Melee Commitment value. A card can be discarded after rolling for melee commitment to modify the die roll (or rolls) in order to pass the melee commitment attempt. For instance, say a unit must roll three dice and each must be less than or equal to two, but rolls a one, a three, and a six. Since two of those rolls “failed,” a card (or cards) can be played to reduce those failed die rolls. A player could discard a 2 and a 3 valued card to reduce the three to a two and the six to a two. Or, one 5 valued card could do the same thing. A unit that passes these checks is able to perform a melee attack (and possible follow-up melee attacks). The four numbers in squares at the bottom of the card are used to determine the number of actions a player can perform during that impulse. The number used is based upon the color of the command rating on the ranking leader’s unit. The possible outcomes of a draw is numerically skewed to provide better results for better leaders and worse results for worse leaders.

Grant: What different types of units are available throughout the different periods?

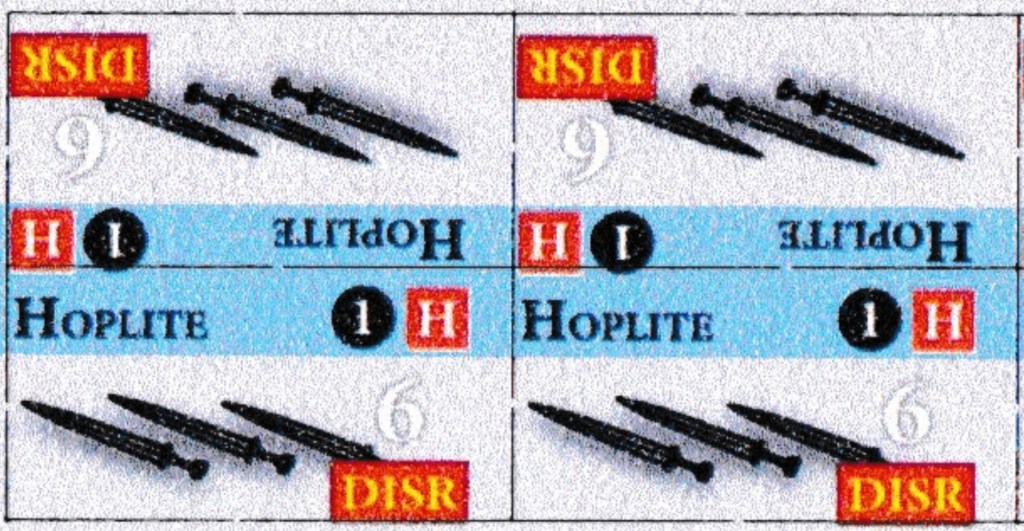

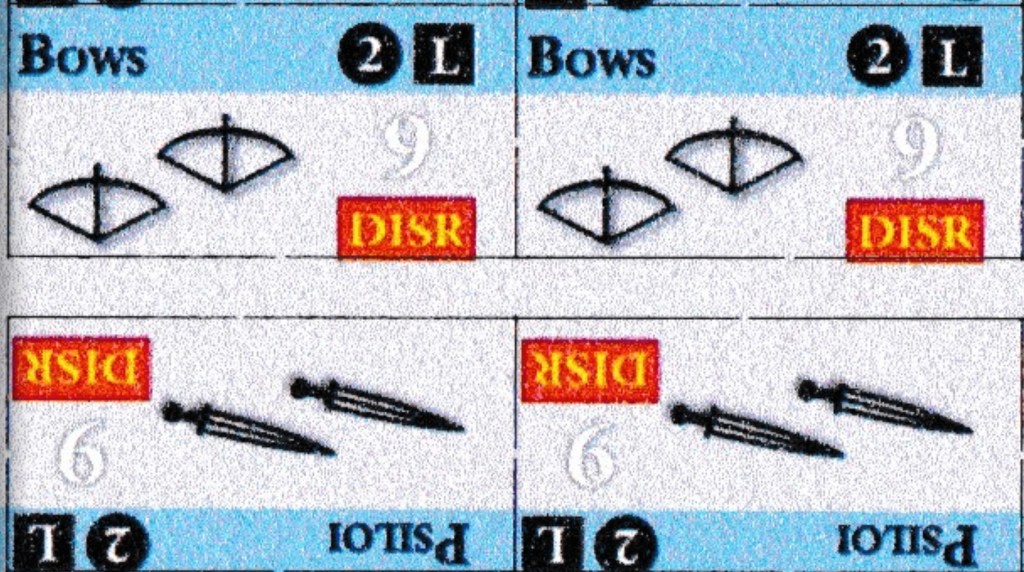

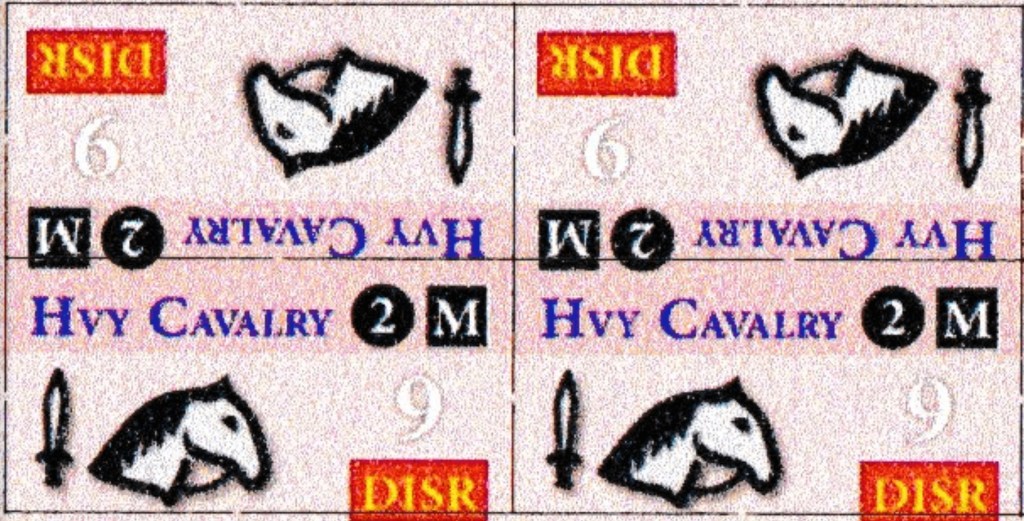

Mike: There are a variety of units available. In the first volume, these include (in no particular order): hoplites (armored infantry), peltasts (lightly armored infantry), spears (masses of mostly unarmored infantry that can perform ranged combat), psiloi (lightly armed and armored … if they’re lucky … skirmishers), bows (like psiloi but with ranged combat ability), immortals (elite Persian infantry), and both heavy and light cavalry. There are also a variety of leaders and camp markers. In later volumes, I’ll be adding Macedonian phalanx units, cohorts, maniples, and maybe some other stuff as well.

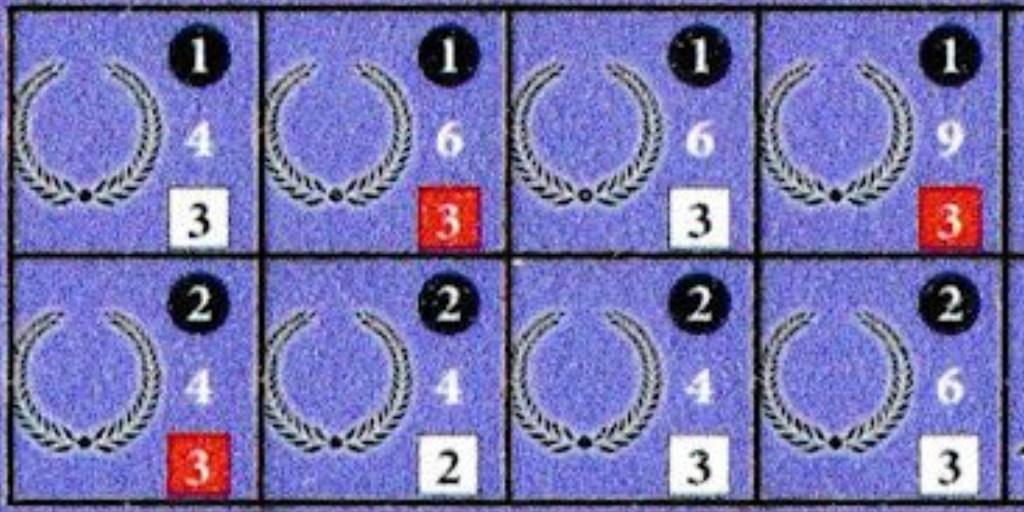

Grant: What is the anatomy of the counters?

Mike: The half-inch leader counters have three values: Command Rank (which determines who’s in charge), Command Radius (how far away a unit can be from a leader and still be part of his formation), and Command Value (providing the overall Morale Value of the army and which colored box to use when drawing for actions). The half-inch by one inch combat units have the following values: The name of the unit (the color of which indicates its broader type: infantry, cavalry, or other). The unit’s missile defense value used when attacked by ranged combat, the unit’s size and density (as I mentioned previously), the unit’s movement value, the unit’s morale modifiers (indicating the number of dice that must be rolled when an enemy unit is attempting to engage it in melee combat; these values may vary when attacking frontally or from the left or right of the unit), and ranged combat values (strength and range for those units that can perform ranged attacks).

Grant: What are Density Markers and what do they represent?

Mike: The Density Markers are placed beneath the heavy infantry units (hoplites in this volume) to indicate the number of ranks that make up the unit. The combat unit itself represents one rank, while the Density Markers represent additional ranks (the game supports up to six, but a scenario may limit how many can be applied). A Density Marker cannot be examined by an enemy player unless a unit is engaged in melee or an enemy unit gets around a heavy unit’s flank. These markers provide a key fog-of-war aspect to the game in that a commander may opt to thin out some of their unit’s ranks in order to beef up others (as happened at the battle of Marathon).

Grant: I notice that the maps use squares rather than hexes. What was your reasoning behind this choice?

Mike: To be blunt, hexagonal grids play merry hell with linear combat. Either a “line” of troops cannot move straight ahead (when facing a hex vertex), or the line itself is not “straight.” In a pinch, the former works better than the latter, but neither work as well as a square grid.

Grant: What advantage do squares provide to your design?

Mike: First of all, they allow units to advance directly forward while retaining an overall linear formation. In this particular design, they also provide a benefit of eight movement vectors instead of six. This allows a unit to move more naturally, but this method does require much higher movement values as the costs to move from square to square is inflated to account for Pythagoras (two points to cross a side, three points to cross a vertex).

Grant: What role does morale play in the game?

Mike: First of all, combat units have to get into melee. If you were negative Fourth Century guy armed with a short sword and armored in a loincloth, would you be eager to get into a brawl with a hoplite in leather armor, a big shield, and a very nasty looking spear? I’m assuming not. This is the effect of morale in the game. When trying to attack an enemy unit, a morale check must be made against just how nasty that enemy unit is. The nastier it is, the more dice have to be rolled, the failure of any of these results in “just say no to melee.” These results are modified by the presence of leaders as well as through the play of melee commitment cards (whose availability is dependent on the quality of leadership). Once a unit gets into melee, it may continue to do so, so long as the impetus (i.e. actions available) is there. Morale rolls are also used to both recover disrupted units (flip them back over to their good-order sides) as well as return routed units to the field of battle.

Grant: How does combat work in the design?

Mike: I think to understand how combat works in Blade & Bow, you need to have an understanding of how ancient combat worked in general. Back “in the good old days,” combat involved masses of dudes trying to shove each other backwards. If successful, vulnerable flanks of a formation would be exposed and the formation would collapse in an attempt to defend itself from the inevitability of “pointed sticks.” A lot of other games on ancient combat (dare I say “most?”) distill combat into a single die roll. I don’t think this really gives players a sense of what’s actually happening. I have opted for a “bucket of dice” approach to combat that I believe works better.

Grant: Why is the combat system a bucket of dice approach? How does this help you tell the story of these Ancient armies and their combat?

Mike: When units are engaged in melee both roll a number of dice based upon their size (the mass of dudes). Light units roll one die, medium units roll two dice, and heavy units roll three dice, plus a die for each additional rank that makes up that unit. This indicates the sheer weight of the two formations pushing against each other. Obviously a larger formation has the advantage here. Then there’s the disposition of the unit itself, which is determined by the result rolled on each die. The lower the value, the more aggressive the unit is, the higher the roll, the more passive it is. One side is shoving harder than the other. Rolls of ones and twos cancel enemy rolls of fives and sixes (and vice-versa). Any uncanceled ones and twos cause hits on the opposing unit. For example, a Persian peltast might roll a one and a five, while an opposing Spartan hoplite with two ranks (itself with one additional rank) might roll a one, a two, a three, and a six. The Persian five cancels the Spartan one, while the Spartan six cancels the Persian one. This leaves one uncanceled Spartan two that causes a hit on the Persian unit. Note that this is regardless of who’s actually attacking. In ancient combat, it’s catch-as-catch-can. Each side may also be able to re-roll results to get a preferable outcome (offensive or defensive). The most dice a side may roll is eight (which means it could be handy to have sixteen dice available, although this is an extreme example that is unlikely to occur in this particular volume).

Grant: What role do Leaders play?

Mike: Leaders play a critical roll in the game. As noted previously, the highest ranking general provides both the morale level of the army, the number of cards that can be held, and determines the number of actions a side receives during an impulse. Leaders are also critical in getting units into melee as well as assisting in rallying and returning units from routed status.

Grant: How do Army Losses and Rout Level determine the outcome of scenarios?

Mike: Each scenario is noted with a Rout Level. Once an army loses this number of units or ranks through routing or destruction, the army collapses and the opposing side wins the battle. It is imperative that a player manage routing units to get them back into combat to avoid a total rout.

Grant: What is the general Sequence of Play?

Mike: First players each draw one card, provided that they do not exceed their hand sizes. Second, players set the number of impulses they each receive during a turn. This value is set by the scenario rules and may be reduced by the loss of leaders or an army’s camp. Third, players determine who holds the initiative for the turn. Fourth, the Impulse Cycle begins where each player alternates the completion of an impulse. The player with the initiative goes first. If players have uneven impulses, one player will have to sit while the other player completes all of their final impulses. During an impulse, a player draws a card to determine how many actions are received during that impulse, based upon the command value of their army’s commander. Each of these actions are spent to have leaders, individual units, or formations of units perform one of the following: Move, Ranged Combat, Melee Combat, Rally, Discard (a card), Purchase (a card), or Pass (doing nothing still burns an impulse). After all impulses are completed, the fifth step involves the management of routing units (do they come back to the battle or are they eliminated?). Finally, the turn marker is advanced and there is a possibility that the battle ends prematurely, based upon a die roll. A game will go at least five turns and as many as twelve (eight or nine is the most likely).

Grant: What role do Camps play in the game? What happens if an enemy Camp is captured?

Mike: Camps are very important. If a camp is lost, the rout level of its army decreases and its morale level goes down. Additionally, it becomes more difficult to bring routed units back to the battle.

Grant: What different scenarios are available in the game?

Mike: The first volume includes Marathon (490 BCE), Thermopylae (480 BCE), Plataea (479 BCE), and Mycale (479 BCE). Each battle has its own map.

Grant: What do you feel the game design excels at?

Mike: Can I say everything? I find that the design works really well, but if I had to pick one thing, I’d say that the combat system goes the extra mile in presenting the bloody struggle of ancient combat.

Grant: What is the future of the system? What other subjects might you attack?

Mike: As I noted early on in these proceedings, there will be at least four volumes in the series, provided that the games are well enough received. The better they do, the more impetus I’ll have to get working on them. Otherwise, they’ll be subject to my design pile (or pileup). Will there be games that use the system for different eras? I won’t say no, but won’t commit to anything, either. So many designs, so little time.

Grant: What other designs are you currently working on?

Mike: At this moment, I’ve got about a half-dozen pots boiling over. Serpents of the Seas (aka Flying Colors Volume 2) has recently been added to the GMT Games reprint list. I’ll be adding several additional small squadron actions to that. The second volume of Captain’s Sea is also in play testing for Legion Wargames. The first two scenario packs for Dawn of Battle (Designer’s Edition) have been released by Blue Panther, and I hope to start testing the third pack’s scenarios in the New Year. I’ve also got a couple of other designs that are nearing completion that will likely make their way to Wargame Vault in the near-ish future. But I’m most excited about my next release from War Diary called Off the Line. Off the Line is a game on man-to-man combat during World War 2. It includes American and German soldiers duking it out over twelve different geomorphic maps across twelve individual scenarios. The game is card-driven and includes a solitaire assistant. Scenarios can be completed in a couple of hours, so the game is ideal for pick-up games and tournament play. I already have plans for lots of expansions that bring in other nationalities along with lots more maps and scenarios. I’m really looking forward to getting it out there.

Thanks for your time in answering my questions Mike and for all of the hard work that you put into your games. I have really enjoyed some of your games and am very eager to play Blade & Bow. I actually have a copy, that is admittedly unopened and unplayed at this point, and I am hopeful to be able to get it to the table soon.

If you are interested in Blade & Bow: The Ancient World at War, you can order a copy for $30.00 plus postage (for a limited time only) from the War Diary Magazine website at the following link: http://wardiarymagazine.com/games.html