A few years ago, we became acquainted with Andrew Rourke through his Coalitions design from PHALANX that went on to a successful crowdfunding campaign. He has since been a busy guy with starting his own publishing company called Form Square Games and also starting the first design in a new series called Limits of Glory that will take a look at the campaigns of Napoleon. We recently reached out to him to get an inside look at the new series and the first volume called Bonaparte’s Eastern Empire.

If you are interested in Limits of Glory: Bonaparte’s Eastern Empire, you can back the project on the Gamefound page at the following link: https://gamefound.com/projects/form-square-games/bonapartes-eastern-empire

Grant: Andrew welcome back to the blog for yet another interview. What is the status of your other Napoleonic design Coalitions from PHALANX?

Andrew: PHALANX have done a great job of developing this game, they have really gone overboard with the quality of the components and making sure all four titles in the series play beautifully. Of course all this attention to detail in development takes time, perhaps more than first thought, so the fulfilment to backers has regretfully been delayed. However the good news is PHALANX have announced that backers will be receiving their games in the third quarter this year and the final version was on display at UK Games Expo recently, therefore people should hopefully have their hands on their copies by September.

Grant: What have you learned about the design process from your first design?

Andrew: I think one of the most important aspects I learnt in the design process is to give yourself a very strict design criteria before you start, then stick to it. For Coalitions, I wanted to design a game with no dice, to reduce randomness of outcomes, no event cards and my design mantra was NO SPECIAL RULES. This forces you to come up with interesting new ways to approach a problem instead of falling back on easier, more well-known mechanics or design options.

Grant: What is your new company? What does the name mean to your vision for its designs?

Andrew: Form Square Games. The Napoleonic period has been my life long infatuation and there is nothing more iconic from this period than the square formation. What attracted me to this symbol were people coming together around a table, often a square or rectangle, to enjoy each other’s company and play games. So the idea of forming a square reflects friendship and the bond we have with fellow gamers because the companions we choose to play with are the reasons we all enjoy games.

Grant: What is your upcoming game Limits of Glory: Bonaparte’s Eastern Empire about?

Andrew: My latest game is looking at the campaign of the French in Egypt between 1798 and 1801. It covers everything from the invasion fleets leaving France trying to avoid Nelson and the British Navy, to the final surrender of the remnants of the French Army to an Anglo-Ottoman force in 1801.

Grant: What is your overall design goal with the game?

Andrew: My design criteria for this game was to come up with a completely new system, using only a single mechanic for every aspect of the game. I wanted the system to be simple to learn but give interesting decision points to players every turn and I wanted the system to be transferable to other campaigns so that once players were familiar with the system they could easily play any game in the series.

Grant: What was the reason for your choice of the title? What does “Limits of Glory” mean in game terms?

Andrew: I remember watching the 1970 Sergei Bondarchuk film Waterloo; in it there is a scene mid-battle where Napoleon is not feeling well. He says to his aid “After I am dead and I am gone, what do you think the world will say of me?” To which his aid replies, “It will say you extended the limits of glory”. This has always stuck with me, if there are limits to glory then it must be measurable, if it is measurable then it must be possible to give it a numerical value. That made me think; what is glory? Is it the outcome of a situation influenced by the skill of the person involved, or is it the outcome that has been dictated by luck? Can glory be considered a combination of skill and luck and do some people have more of this and some less? This is what I wanted to consider in my game design.

Grant: How does the game examine the influence of luck and skill on the timing of events during Bonaparte’s adventures in the East?

Andrew: I believe luck is what happens, skill is how you deal with it. Certain events such as storms and plague are just down to luck, others like perhaps arriving a day too late or not having enough food could be put down to bad luck or poor judgment. However all of these situations could be mitigated by skill; travelling at the right time of year, strict quarantine adherence, marching faster and planning stores better.

I wanted to design a game that put both players in a situation where they didn’t know what might happen next, so no handful of event cards where they could plan their future moves. Instead, the Event Clock drives the game with randomly generated historical events that will occur in roughly the correct chronological order, however, neither player knows what’s coming and both have to react to the situation as presented on the board. This means strategic reserves must be kept and positioned wisely. Decisions about the strength of armies needs to be weighed against the need for garrisons and most importantly, it means decisions about placing the right commanders in the right places.

A player who has skillfully weighed up the needs of all his forces and positioned them well, should be able to overcome whatever luck throws at them with the randomness of the Event Clock.

Grant: What is the scale of the game and the force structure of units?

Andrew: The game is all about managing your commanders and using their Glory wisely. Units have a numerical value that is interchangeable like currency; a unit of 5 French infantry could be broken down into a unit of 2 and a unit of 3 if desired. Each unit represents roughly 1,000 men; the organization of the French invasion force is well documented and it is easy to get an idea of how many French landed in Egypt. In the game, the invasion phase determines how many French units arrive, depending on how well the French player does. This could be as low as 17 infantry, representing 17,000 men, or as high as 26 infantry, representing 26,000 men. Reliable figures for the Mamluk and Ottomans are much harder to establish but again, each unit represents 1,000 men.

The command structure is a very important element of the game; the Glory of the most senior commander in a space is used to mitigate the situation and junior commanders always accompany their more senior commander in the chain of command until they are detached to perform tasks separately.

Grant: What different units are represented in the game and what advantages do they bring to the battlefield?

Andrew: The units in the game are Infantry, which is the standard combat unit for all sides. Cavalry, the Mamluk’s and Ottomans have plenty of these, though the French arrive with none and have to mount their cavalry with locally obtained horses through the Event Clock. The British have no Cavalry. The differences with Cavalry units are that they count double in combats, though following the first assault round of a siege, they no longer contribute to the siege. Artillery units count as triple in combats and sieges.

Naval squadrons are also represented; they may fight enemy squadrons, perform blockades or add their combat strength to sieges fought at coastal built up areas.

Grant: What is a Glory Rating? What role does it play in the game?

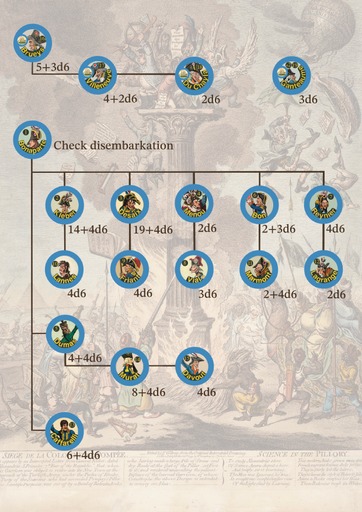

Andrew: A Glory Rating represents a combination of a commander’s historical skill and how lucky they appear to have been in the campaign. All named commanders have a Glory Rating, which is established immediately when his position marker is placed on the map board. This is determined by a mixture of a number of dice which are rolled and totaled and a fixed number that may also be allocated to that commander. In this way each commander has a certain degree of randomness applied to their Glory Rating. For example, Kleber’s Glory Rating is 14+4d6, where as Menou’s is only 2d6.

A commander’s Glory is reduced to re-roll dice during the game at the rate of one Glory point per single re-roll. Any dice can be re-rolled once by the owning player and any successful combat dice of an opponent can be forced to be re-rolled once.

Grant: What area does the Map cover? Who is the artist and how does their style assist in creating theme and immersion?

Andrew: The Map covers a distorted and abstracted area of Egypt, Syria, and the Mediterranean Sea. All the art in the game is by contemporary political satirical cartoonists, James Gillray, Isaac Cruikshank and George Cruikshank.

The European public at this time would have had no idea what Egypt was really like. They depended on paintings and written descriptions, but more importantly, for the masses their only depiction of events would have been through the cartoons of artists like these. So in a way these cartoons are a primary source of information about how the public saw these campaigns.

Grant: What purpose do the various numbers appearing in each space on the Map serve?

Andrew: Spaces on the Map each have a value of between 1 and 4; this indicates the number of dice to be rolled to activate elements in that space. Dice rolls succeed on a 5 or 6 and fail on 1 to 4. Only one dice success is needed to activate the space. Therefore spaces with a value of 1 will be harder to move out off compared to spaces with a value of 4.

Grant: What aspect of the campaign does this reflect?

Andrew: Low numbers can represent areas of desert that were hard to move through or large distances of ocean that took a long time to cross. Higher space values represent a better ability to move through those areas or small distances.

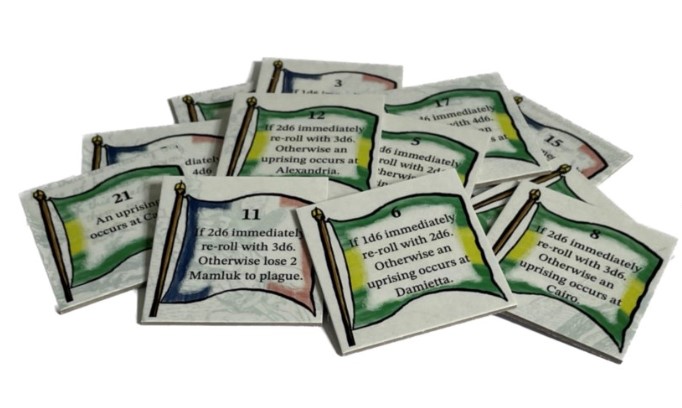

Grant: What is the Event Clock?

Andrew: The Event Clock is the mechanic that drives the game. There are no event cards in the Limits of Glory Series; instead the Event Clock introduces events. There are twenty-four numbered flags on the Event Clock each with an event written on it. The flags represent who will benefit from the event.

At the start of each turn in the Conquest Phase an event is rolled for, initially by rolling 1d6. The number rolled corresponds to the event that is to occur immediately, once the event has occurred the flag is covered by a second event tile unless the event is repeatable, in which case it is never covered. Some events indicate that another dice must be added to the event roll for the rest of the game, so in this way players start by rolling 1d6 for an event, they progress to 2d6, then 3d6 and finally 4d6. This means that as the game progresses more and more events become possible but the probability of particular events happening changes as the number of event dice to be rolled changes. Players need to allow for this in the decision making process during game play. Some events may never happen and others may occur multiple times.

Once 4d6 are rolled for an event then a score of 14 will end the game. This represents the fact that talks for European peace were progressing at the time, in Amiens, in France and no one in Egypt knew when a boat might arrive from Europe saying that a peace treaty had been signed, meaning fighting had to stop.

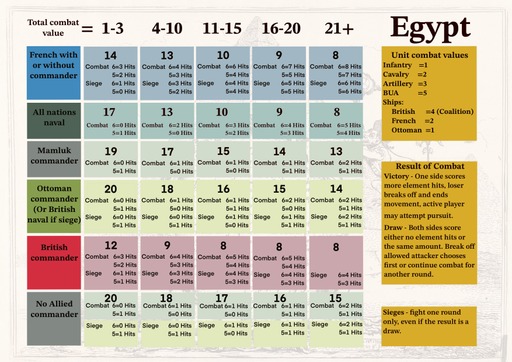

Grant: What is the makeup of the Combat Chart?

Andrew: The Combat Chart is a grid, combat strength running across the top and the type of troops and their commander running down the side. Players cross-reference the combat strength of their forces with their commander status and place their wooden pawn in the box that intersects where they meet. The box indicates the score needed when all four combat dice are totaled. Once this score is equaled or exceeded, then any successful rolls of 5 or 6 inflict hits as indicated by the box.

Grant: How does combat work in the design?

Andrew: Combat is very asymmetric in this campaign as disciplined and trained French troops were fighting what could almost be regarded as medieval opponents in the Mamluk’s, who were highly trained but not trained to face a European enemy.

Using the same mechanic of 5’s and 6’s being a success, each player rolls four dice whatever the value of the space they occupy. If a commander with remaining Glory Points is present, the player may re-roll any failures, then both players may require opponents to re-roll successes. Re-rolls or requests for opponent re-rolls expend one Glory Point for each re-roll from the most senior commander present or a more junior commander in the same space designated as leading the troops before the combat began.

A player’s total final score after all re-rolls, adding together all four dice, must equal or exceed the large number printed in the box of the combat table containing their combat marker for any loss to be inflicted on the opposing elements. If a sufficient total is scored, successful scores (5’s and 6’s) reduce the opponent’s strength by one non-commander element for each combat hit inflicted. The player receiving the hits decides which elements to remove.

To reflect the asymmetric nature of the combats, generally the French require lower total scores to inflict hits and when they do successfully score hits often they score more element hits per successful dice than the Mamluk’s or Ottomans.

Grant: What is the Commander Chart? How does this work?

Andrew: Each player has a Commander Chart that shows the chain of command and the seniority of commanders, it also displays the Glory Value of each commander as a number of d6 rolled plus any fixed amount. During set up all position and Glory markers are placed on the Commander Chart in the appropriate position for ease of access and clear understanding of who has been deployed to the board and who is currently accompanying their more senior commander.

Grant: What is the general Sequence of Play?

Andrew: A complete turn consists of an event from the Event Clock followed by the French player moving elements and fighting combats and sieges until all his momentum markers are placed or he declares the end of his turn. Then the Allied (Mamluk, Ottoman and British) player moves, fights combats and sieges until all his momentum markers are placed or he declares the end of his turn. Due to the interactive nature of the Glory system, both players are involved throughout the turn whether they are the active or non-active player. These three steps are repeated until the game ends.

Grant: How is victory achieved?

Andrew: The French must take control of all the built-up areas that award victory points in Egypt and Syria, plus escort the savants to the Valley of the Kings and maintain them there. If these conditions cannot be met, the French must retain control of Cairo and Alexandria, while keeping more victory points than the Allies and hold on until the Peace of Amiens confirms French control over Egypt, giving them victory in the game.

The Allies must prevent the French incursion into the East with any force available. They must have simultaneous control of Cairo and Alexandria with any combination of British and Ottoman elements at the end of any allied turn, to secure an instant allied victory. If this is not achieved, they will need to have more victory points than the French at the Peace of Amiens to triumph.

If, at any point in the game, a player feels they can no longer achieve the conditions for victory, they may concede the game to their opponent.

Grant: What are you most pleased about with the outcome of the design?

Andrew: The fact that one simple mechanic can produce a game with so much depth and present the player with some really difficult decisions. The Event Clock has also been great to design, taking many iterations and lots of maths!

Grant: What type of experience does the game create for players?

Andrew: Feedback from play testing shows that players really feel like the theatre commander, having to make important decisions on what needs to be done and how urgent it is. Commanders only have so much Glory and when it’s gone it’s gone so the balance between achieving objectives quickly and becoming exhausted is very delicate and puts the player under considerable pressure.

Grant: What other designs are you currently working on?

Andrew: Limits of Glory is designed to be a series, the second game in that series, Maida 1806, is already designed and ready to go and depends on the success of Bonaparte’s Eastern Empire. I am currently working on the Vendee, which will be the fourth title in the series and is proving very interesting. The third title will be a small game designed to be playable in about an hour, covering the British invasion of the island of Santa Maura in 1810.

If you are interested in Limits of Glory: Bonaparte’s Eastern Empire, you can back the project on the Gamefound page at the following link: https://gamefound.com/projects/form-square-games/bonapartes-eastern-empire

The campaign will conclude on August 1, 2023 at 3:00pm EST.

-Grant

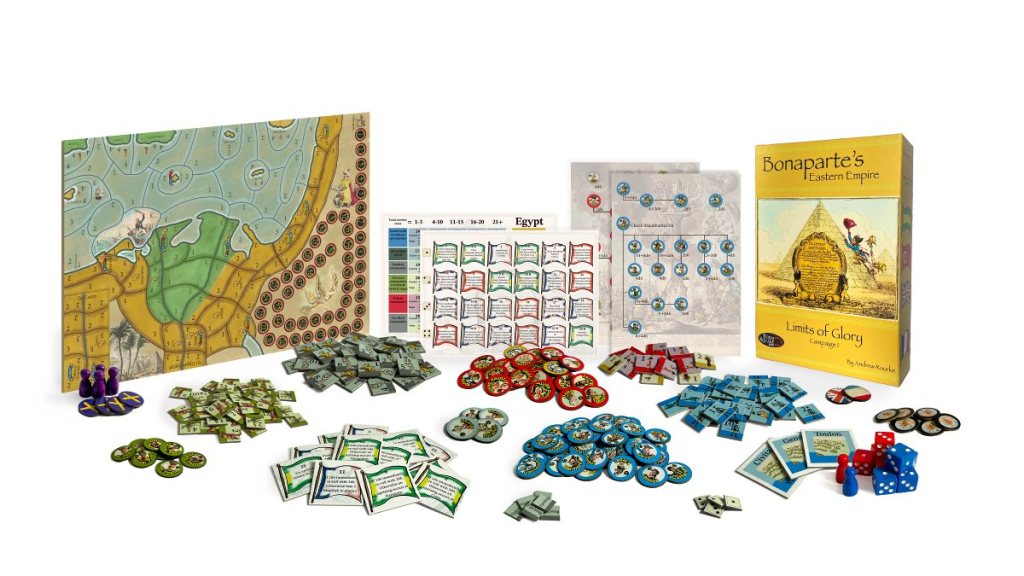

All the illustrations and artwork used throughout the game on all components, tables, charts, the map and the box, are taken from contemporary political satirical cartoons. Their creators’ work brought to life events of the time to a public who had no access to photos, videos, films or social media. Many of the images depicted would never have been seen by the artist. Their imagination of often written accounts, constructed a critical and at the same time ludicrous view of the great and the good from all sides of the political divide, friend or foe.

You can find more information and further reading on all three cartoonists by following these links: