A good American Civil War game is pretty hard to beat and John Thiessen has done several good games with Hollandspiele over the past few years including More Aggressive Attitudes, Objective Shreveport and Hood’s Last Gamble. Now he is starting a new series called the American Civil War Operational Series and its first volume Our God Was My Shield. We reached out to John and he was willing to share the inner workings of the design.

Grant: First off John please tell us a little about yourself. What are your hobbies? What’s your day job?

John: Music, movies, doing things with my girlfriend. Recently I’ve retired due to health issues.

Grant: What motivated you to break into game design? What have you enjoyed most about the experience thus far?

John: Like others in the hobby, I eventually started tinkering with already published games. From there I went ahead and started designing whole games. The most enjoyable parts of design are doing the research and also trying to come up with ideas that are turned into rules or charts that model historical processes fairly accurately while being as simple as possible.

Grant: What designers have influenced your style?

John: Certainly whoever invented hexes for map grids and the basics of movement and combat for wargaming. I started wargaming in the 1970’s, face to face and solitaire, and experienced the days of Avalon Hill and SPI when they were at their peak.

Grant: What do you find most challenging about the design process? What do you feel you do really well?

John: Making maps and the routine process of typing aren’t exactly the most enjoyable part of the design process for me.

I feel that I translate historical activity into rules and procedures that are playable, not too complicated, and at the same time are historically valid.

Grant: What designs have you completed to date? What do you feel those designs have taught you that help in your current efforts?

John: I have completed some other American Civil War operational games, a Napoleonic operational game, an ancients game, and a couple of World War II games. I try to learn something every time I design a game. The funnest part of the design process for me is creating rules that reflect historical aspects while at the same time are playable. Translating historical processes into game rules, in other words.

Grant: What is your game Our God Was My Shield about?

John: This is about the campaign in the Shenandoah Valley in 1862, when Jackson’s command went on the offense, and then the North eventually sent reinforcements to the area to halt Jackson’s advance and to push him out of The Valley.

Grant: What was your inspiration for the name and what do you want it to convey?

John: My original title was a rather plain Jackson’s Valley Campaign, but Hollandspiele found a quote by Jackson that gave it a more unique title.

“Our God was my shield. His protecting care is an additional cause for gratitude.” – Stonewall Jackson

Grant: What type of system is your American Civil War Operational Series? What type of experience is it designed to create?

John: It is a hex and counter wargame and of classic I go-you go type. I hope that the accessible playability of the design, combined with historical modeling and flavor, give players a good experience. The series is of an operational nature, therefore regimental tactics and counter facings are not involved. The games are of unit maneuver and battles.

Grant: I see it described as a “card-assisted operational sandbox”. What does that mean to us as gamers?

John: Card assisted in this case, as in all of the games in the series, means simply that the cards are memory aids for events that can take place. These events can be deliberately chosen and used by the players. Sometimes when the event is accomplished the card is removed from the game, and other times it is returned to play and can be used again.

Grant: What from the history of Stonewall Jackson’s 1862 Valley Campaign did you want to model in the game?

John: Maneuver and battle at the scale of the game is modeled. Also various individual aspects of leaders are shown, like the benefit to the Confederate cavalry leader in cavalry combat, which is justified historically, but there’s no fudge advantage for Jackson in combat because he wasn’t very good tactically, especially when attacking. I’ve seen some instances in books and ratings of Civil War leaders that frankly were not very accurate. Simplistic reputations have been created over time, but the fact is that Banks was better than some of those reputations and Jackson was not as good.

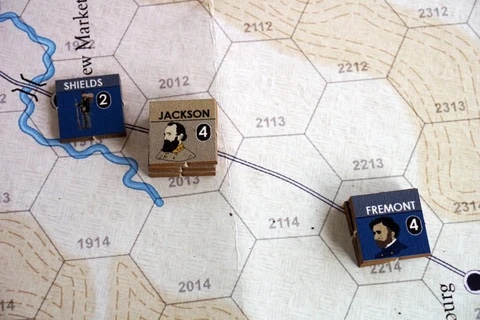

Grant: What is the scale of the game and the force structure of the units involved?

John: The turns represent one day, and each hex represents 4.9 miles across. The units are generally brigades and divisions.

Grant: How does the system hide individual units and their strengths from your opponent? What kind of experience does this create?

John: Players can see the units on the map, but their combat strengths are displayed on a chart. Players therefore are aware of the enemy but not sure of the exact combat strengths. This creates some really blind attacks and guessing but creates a nice real feeling for the battles.

Grant: I see where the game is described as a “tense dance of cat-and-mouse maneuvers” and that when attacks are made there’s a chance your opponent might slip away. What does this mean and what are you trying to represent from the history?

John: When one side’s unit or units tries to attack an opponent occupied hex, there is a chance that the opponent can retreat before combat. This is historically accurate in the sense that opposing forces in reality can be moving simultaneously, and therefore a force that is intended to be attacked can march away. That’s not always the case though. There are times when the attacker can force a battle due to catching the other side by surprise, and this is possible in the game. Of course, retreat before combat is the defender’s choice and can choose to stand and fight at any time.

Grant: How important is the concept of coordination of forces for attacks? How is this coordination attempted and what are the results of failure?

John: This concept of attack coordination is simply that if an attacker makes an attack by units in more than one hex, then there’s a possibility that there are coordination problems among the attacking units. This shows the difficulty in coordinating attackers pre-20th century. One of the attacking columns might arrive late, or orders might be misunderstood or disagreed with. Roll a die and find out! If there’s a problem with attacker coordination, there’s a simple detrimental column shift on the CRT.

Grant: What is the anatomy of the counters?

John: The counters are very simple and show the type of unit and its movement allowance.

Grant: What different types of units are represented on both sides?

John: Infantry and cavalry are represented, and significant leaders are included. Artillery is distributed among the units and is not represented by separate counters.

Grant: How do the units differ? How are cavalry units used?

John: Cavalry units are quite small in strength as compared to the other units in the game, but their advantage is that they can move faster and slow down enemy troops. They can therefore be used to screen and protect slower units. While the cavalry is in the game, being so relatively small, doesn’t add strength to battles involving infantry, pure cavalry vs. cavalry actions can occur.

Grant: How are cards used in the design? Can you show us a few examples of these cards and explain their effects?

John: The cards represent special events, and they simply explain the effect of the event. Sometimes when an event is used it is retired from the game, and other times the event can return later in the game. An example would be a Forced March card which adds 1 to the movement allowance of one unit or stack for the player playing the card. It is possible for this card to return to the player’s hand later. Another example is the Aggressive Ewell card. This allows the South player to ignore the command die roll for Ewell’s command this turn. This card is permanently removed when played.

Grant: What area does the map cover? Who is the artist and what research did they do to get details of the Valley correct?

John: The map shows the Shenandoah Valley area of the historical 1862 campaign, from Staunton in the south to Williamsport in the north. The map artist is Ilya Kudriashov, and I made the original map by hand drawing because I don’t know how to do computer graphics.

Grant: How does combat work?

John: At this scale combat is voluntary between adjacent enemy units. If the player whose turn it is wants to attack, then a straightforward odds based CRT is used. There is a possibility that the defender can retreat before combat. If combat takes place, besides the result from the CRT, there might be additional effects depending on terrain and if the attacker attacked from multiple hexes.

Grant: What is unique about the CRT? What different results are included?

John: Results on the CRT are retreats, disruption, elimination, and strength point loss. There are also possible additional strength point losses on the Casualty Table, and possible other effects if the defender used a defensive works or occupied a Woods hex. I decided to make the effect of woods on combat variable, meaning a die roll, so that players can’t be sure what the effect will be if having combat in a wooded area. At times in the Civil War the defender or the attacker could be helped or hindered by this type of terrain.

Grant: What is Disruption Recovery and how does it affect the game?

John: There was originally a typo in an earlier version of the rules that called this Distribution Recovery. It’s actually Disruption Recovery, and that refers to units recovering from being disrupted in combat.

Grant: How are defensive works built and what benefits do they offer?

John: Defensive works can be built and then improved upon. An infantry unit with 2 or more strength points, if not moving or attacking, may build or upgrade. The benefit is to the defender in combat. Players roll for the effect, which can be: ignore defender retreat, no advance after combat, or decrease the defender’s casualties. Also there’s a CRT column shift in favor of the defender at the highest level of defensive works.

Grant: What are the victory conditions?

John: Victory is achieved by winning combats and occupying certain locations. Players gain Victory Points for successfully achieving these things.

Grant: What are each side’s general strategy considerations?

John: Both sides have geographical considerations in trying to take certain towns and at the same time defend certain locations. Generally the North player is weaker and scattered in strength at the beginning but can expect reinforcements to arrive. This may give the northern side the units to counterattack, though still having to deal with fragmented commands. Confederates are pushing north to take towns, but have to watch out for growing US strength. The South side has a more unified command structure and therefore has an easier time dealing with command.

Grant: What are you most pleased about with the design?

John: I think that all of the historical elements at this scale are represented in a playable way: movement, combat, supply, and leaders. Players can get a feel for the specific era without a heavy rulebook.

Grant: What has been the experience of your playtesters?

John: I have received comments that I’m pleased with, that players can get into the game quickly, have some choices to make, and have fun with the situation without wrestling with complicated rules.

Grant: What other battles are you considering for inclusion in this series? What type of unique rules will be required for these?

John: I have worked on a game of the Peninsula Campaign of 1862, and that’s actually mostly completed. As for any game in the series, there will be some unique rules added to the common rules. Aspects of leaders and cavalry will differ in the other games. Supply will have some variations, and they will always be kept as simple as possible while retaining historical reflection.

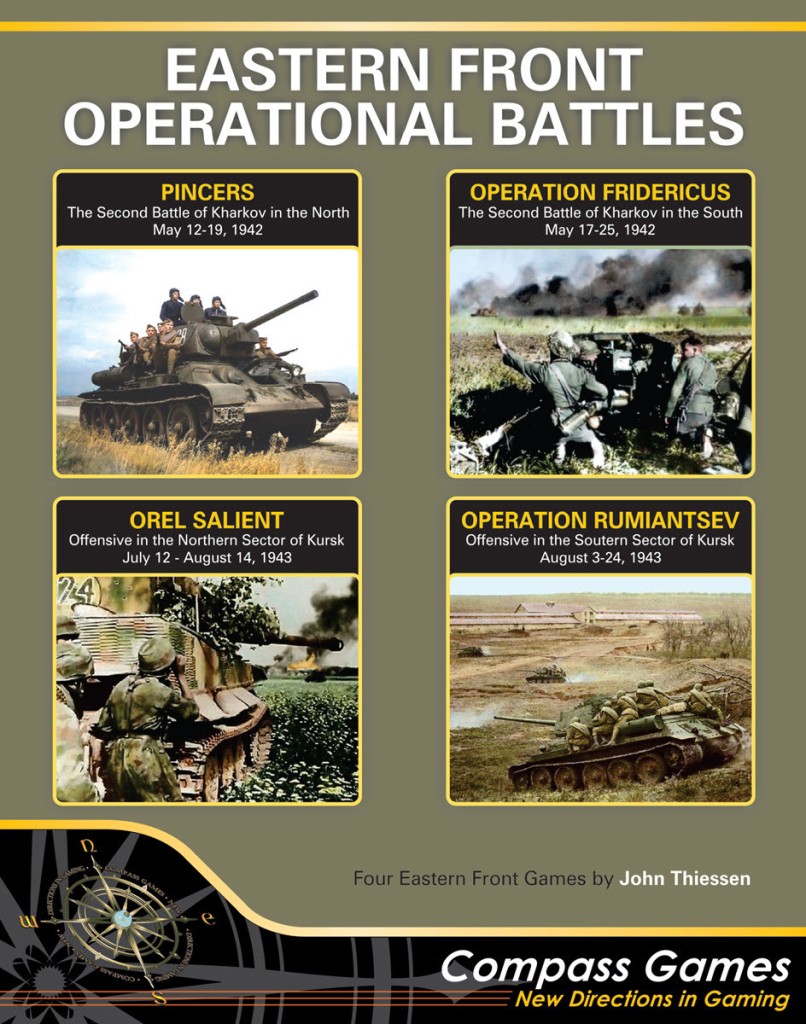

Grant: What other games outside of this series are you working on?

John: Now I’m working on a set of four WWII East Front games for Compass called Eastern Front Operational Battles. This quadrigame, as it’s being referred to, has been announced, though I don’t know exactly when it will be finalized and published. These are operational level games with a common standard rule booklet. The four games are “Pincers” (the 2nd Battle of Kharkov in the North) and “Operation Fredericus” (the 2nd Battle of Kharkov in the North) (1942), and “Orel Salient” (Offensive in the Northern Sector of Kursk) and “Operation Rumiantsev” (Offensive in the Southern Sector of Kursk) (1943).

Thanks for your time John and I am really interested in this new Our God Was My Shield as I love games that focus on maneuver.

If you are interested in Our God Was My Shield the game is available and you can order a copy for $50.00 from the Hollandspiel website at the following link: https://hollandspiele.com/products/our-god-was-my-shield

-Grant

Any chance on a video review/walkthrough of this game? I’d really like to see a few more videos on this one.

LikeLike

The designers upcoming “Operation Fredericus” game will actually cover the 2nd Battle of Kharkov in the SOUTH – just a typo.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Volume 2 coming soon next year )))

LikeLiked by 1 person