We may be destroyed, but if we are, we shall drag the world with us – a World in Flames!

-Adolf Hitler

That quote inspired Harry Rowland’s title for an epic globe spanning conflict simulation about World War II. It is also the first strategic game about the Second World War I ever played (it’s not the first wargame I played however; I was introduced to strength factors and CRTs by way of Freedom in the Galaxy).

Down Under

As a boy I only really caught the tail end of the 80s and didn’t really fully connect with the 90s, so my own experience favored a mix of both with a big lean to the former decade. Lots of stuff happened in the 80s and culturally speaking various people, events and countries shaped the decade. Japan the corporate powerhouse, the US had Reagan, Wall Street, MTV and the arcade wars. England had Margaret Thatcher. Live Aid with the most impressive rock bands of the decade performing for a world wide audience. Perestroika and the end of Soviet communism. The list goes on.

I’m going to sum up Australia’s contributions to the 80s (knowing full well I’m going to be harassed and insulted) as AC/DC, Mel Gibson (pre-meltdown), Nicole Kidman, Crocodile Dundee and (today’s topic) World in Flames (WiF from here on out).

A Global Epic

WiF depicts the Second World War in all its grandeur. First published in 1985 it’s gone through several iterations and additions up to the present day. The absolute proclivity of editions – eight if you count the collector’s edition – along with spin off’s such as America in Flames or Patton in Flames to name two and various expansion sets (Convoys in Flames, Ships in Flames, Cruisers in Flames, Aircraft in Flames, Noodles in Flames, etc.) has led many a World in Flames aficionado (collectively known as WiFers – pronounced “Whiffers”) to affectionately (and not so affectionately) nickname the franchise: “Wallet in Flames”.

My own introduction to this particular family of games started with a loan of the 2nd edition from my father’s old college buddy who had a sizable game collection of his own. He happily let a pre-teen borrow the game fully convinced that I would be flummoxed by a level of rule complexity that he found fiddly and exhausting. His attitude was no doubt that of a somewhat condescending adult amused when a child takes on a challenge he can’t possibly understand. “This kid doesn’t know what he’s getting into.”

When he found out I had managed to solo two full global war campaign games in a three week span he laughed at his own preconceptions and basically told me to keep the game for as long as I wanted. I still own that worn down and beaten copy in my library. Never underestimate a teenager with oodles of free time. Ah the curse of our hobby; when we have the time to play, we don’t have the money, when we have the money we hardly have any time to play (unless you’re Mark Herman — then you have both).

The Global War that fits on your Dining Room Table

Prior to the final edition this game came with just two maps just a little bit larger than your traditional 22″ x 34″ map. This meant that you could play a Europe / Pacific only war in about the same space as you play any one map game nowadays or combine both maps to fight the whole of World War II in the same space as Unconditional Surrender and its brethren. It’s almost a given that most recently designed theater wide games end up being two map games but WiF was charming at the time for managing to fit so much in a compact size.

It did this primarily by focusing its hex map on detailing the major areas of conflict up to the Axis High-water mark in late 1942, early 43, with other notable map areas introduced via the “Off Map” box (such as northern Norway, the Urals, Western India, etc). The fact that sea movement was accomplished via Sea Zones (with boxes representing time spent by units at sea) meant that the world’s oceans were relatively easy to represent in a compact form allowing for both maps to have easy seaborne communications links for moving between the theaters.

Not that this arrangement is ideal or perfect by any means. For naval forces, the off map boxes worked like a charm since all the action occurs in the sea boxes, but for ground combat based on hexes the fit was awkward and the first set of rules weren’t very good. The 5th Edition added a bit more sense to the chaos and worked a little better.

Evolution Complete (maybe)

Like a few other grand strategy games that evolve over the decades, World in Flames can be split into three phases of development. Throughout the first four editions, the rules and content were kept mostly the same with some polishing around the corners, updates to the map (primarily in the off map boxes where New Zealand was eventually added) and a few cosmetic upgrades.

Things really started picking up with a product called Days of Decision that added components to the 4th edition giving minor nations their own force pools for the first time (except for the traditional axis minor nations of eastern Europe which always shared the German force pool). Until then, all minor countries shared the same force pool and you drew randomly whenever you had to set them up.

This lead to the 5th edition which included the 4th edition upgrade counter sheet as part of the main product along with some significant rule and counter changes. This is the transition period of complexity, when the expansions started adding new values, new maps and new rules. Africa, Central Asia, Scandinavia, America. If you look at the 5th edition Planes in Flames expansion, for the first time air units had individual ranges and specific aircraft models and pictures. Ships in Flames did something similar to give you names capital ships (though 5th edition already started with names in pairs). Units started having calendar entry dates, and so on.

The third phase of development consolidated the transition into the 6th edition of the game (touted as the final edition) which revamped and consolidated the core concepts of all these expansions into a new core package that made mainstream the changes to the air and ship counters from the expansion, consolidated HQ into powerful units of their own and expanded from 2 to 5 maps changing the scale somewhat but now giving more breathing room to the traditional theaters of where while including all of India and eastern Africa and giving America its own map and reshaping off map land boxes into off map hexes that had a a different scale but allowed a better fit for movement and geography (though there is still a separate Scandinavia map if you want one).

From then on the 6th edition still had a deluxe version which grouped all of the different “in flames” expansions into one package and now a Collector’s edition has come out which made one more cosmetic change which was to change the map terrain to something a little less…garish (the mountains from the final edition are quite infamous)

Full Impulse Power

The heart of what makes WiF tick is the impulse system coupled with initiative. Some games have a set pace of offensive operations (like the action rounds in Paths of Glory), or you decide how much activity will occur on a given “front” or theater (like Offensives, Attrition and Pass options in Third Reich) for the current turn which is a moderately long season. Then you execute that option.

In this game offensive operations are conducted in impulses (not unlike action rounds), the number of impulses is heavily dependent on weather, with good weather generally providing more impulses available to move and fight and bad weather causing operations to slow down and end the turn quickly. Furthermore, this is done via a die roll check after each 2nd impulse (guaranteeing that each side, Axis & Allies, get the same number of impulses), which means the actual number of impulses is not known but the weather chart makes it easy to figure out the minimum number of impulses that will occur. This provides an interesting level of uncertainty. Imagine if in Paths of Glory or Twilight Struggle you played a variable set of action rounds and you didn’t know after the 3rd or 4th if the turn would end suddenly!

Air, Land & Sea

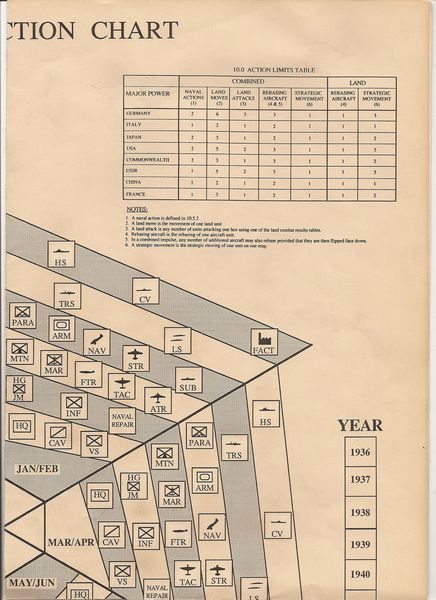

During each impulse, the player has to decide what kind of impulse its major power countries will execute. You have the option of Naval, Land or Combined impulses (later editions added an Air Impulse if I’m not mistaken). So Germany could do a Land impulse while Italy and Japan chose naval impulses.

As the name implies Naval and Land impulses primarily involve moving all your ships and ground troops. Though ground troops can be transported if already sitting in a port with a transport unit (a pick up and deliver mechanic near and dear to the heart of Eurogamers everywhere). Air units are available in both kind of impulses to fly naval air missions (naval) or ground strike and ground support (land). The Combined impulse allows you to move a little bit of everything; subject to each nation’s limits on a chart dictating how many air, land and sea units they can move with and fight in such an impulse. It is also the type of impulse necessary for strategic bombing missions.

The choice of what kind of impulse to execute will drive your overall strategy and tempo of operations. Note that an impulse is chosen per theater. The United States has forces in Europe and the Pacific, so they choose two separate impulses per major theater of war. The same goes for the British Commonwealth and the Soviet Union. The Axis powers generally only have one units in one theater and so don’t have this added flexibility (or complication depending on your point of view)

Strategic Warfare

Most games tend to to treat strategic warfare somewhat abstractly at this level. You commit bombers to a bombing box or subs to a general Atlantic or Pacific box, you add escorts or interceptors and roll a die or two and inflict some generic economic losses. Not WiF. I mentioned factories earlier when referring to production. Such factories exist as actual locations on the map. So too, do the resources. When it comes to such warfare strategic bombing can inflict damage to factories, reducing the potential number of build points. I believe there is also an optional rule allowing for bombing of oil resources. This means you need to build those bombers and put them in the right airbases giving them the range to reach exactly the factory you are bombing. The opponent needs fighters within range of defending said factories making strategic bombing every bit an operational challenge as planning a big eastern front offensive or sweeping central pacific naval strike.

On the sub warfare side of things, resources (and build points) can be transported by sea, a Major power can flip one of its transports to its CONVOY marker side and put it in the sea area. Such a chain of markers across adjacent sea zones is required to establish sea trade and transportation of economic resources. Ports that are connected to this “chain” and move resources across the oceans with these convoy markers. Subs can attack areas with such markers and inflict resource losses. This is another game unto itself especially for the British Commonwealth which has most of its industry in Britain but the vast majority of its resources scattered across the globe. Naval escorts and subs fight at the end of the turn however; unlike strategic bombing it did not occur during an impulse.

The effects of strategic warfare impact the production of the next turn. Some bookkeeping is involved since you need to track the amount of resources moving through convoy pipelines and which factories have been hit, but nothing really cumbersome since the total number of points never goes beyond double digits.

Blitzkrieg!

/pic1209968.jpg)

When it comes to the land combat system things are more traditional with combat and movement factors with the usual ratios for battle. There is an overrun system where you spend movement points to overcome puny garrisons (ostensibly to prevent speed-bumps) but at the heart of land operations are the two CRTs. One is called the Assault CRT and the other the Blitzkrieg CRT.

Before delving into the differences it is important to point out that all ground units in this game are a single step, the back side denotes a spent unit that has already moved and attacked. Ground strikes can flip troops to their back side generally reducing their strength by half but even further if they are isolated and out of supply. Essentially units that are sunny side up are at full strength and ready for action. After moving and attacking most of the time they are flipped. Special headquarters units can be used to reorganize and flip back a small number of units so they can keep fighting in the next impulse. However, another way to keep units fit and running is good combat results.

The CRTs in general have asterisked results which allow attacking units to maintain their front side up. The Blitzkrieg table having more of these results than the Assault table. That’s because the nature of both table sis different: The former is used primarily to win terrain but not really cause large combat losses, while the latter is much more bloody and likely to halt your offensive. Naturally the Blitzkrieg table requires armored formations to take advantage of but also favorable terrain (not, swamps, mountains or cities). The Blitzkrieg table also gives the “B”-Breakthrough result allowing for armored exploitation.

/pic2364487.jpg)

While the defense can lose units in combat, often they will suffer “Shattered” results which means the troops have been broken but will reorganize and reappear; in practical terms this means they are placed on the production spiral for the next turn and arrive as regular reinforcements. This emphasizes the fact that unit destruction did not occur but enough damage inflicted to render them ineffective for some time until its core elements reconstitute. It’s a choice presented to the offensive player; what is more important? destroying enemy forces or capturing territory?

Naval Power!

/pic1209966.jpg)

The most original aspect of World in Flames is the naval and naval air operations. It all starts with the sea box. This box has cells numbered from 0 to 3 (up to the 5th edition anyway, starting with the final edition they added box #4). Each cell represents the amount of time a naval unit is spending in the sea, the theory being the more time you spend in the theater the more you are scouting and securing the sea lines of communication and more likely to face combat. Conversely, the closer to the 0 box the less you are engaged and just passing through and the more likely you are to being surprised. It costs as many movement points as the number in the box to be put there. Once a unit settles into a sea box in an naval impulse it can only go back home and flip (aborted or finished) or slide to a lower numbered box.

In order to initiate combat you must search and find the enemy at sea. The way the mechanics of naval search work is through simple comparison of die rolls, only those units in boxes numbered higher than your roll will be involved in combat. If you didn’t manage to roll low enough your units didn’t find the enemy. Obviously this means that in general units in the 0 box aren’t actively looking for trouble. If only one side rolls low enough that means those forces found somebody and they get to choose which enemy sea box to attack instead of mutual forces finding and attacking each other. The 0 box is not necessarily a safe space, escort your transports people! And amphibious invasions require transports with troops to be in the 2 or 3 box at sea. Likewise naval fire support (whether from carriers or surface ships) also must be in the higher numbered boxes. If you roll too high then your units will be surprised.

There are two types of combat, surface and naval air. If surface you total those factors from all involved ships. If naval air you add carriers, and any air units assigned naval air missions. If both sides have carriers or aircraft at sea then an air battle is fought first (which I’ll get to later).Combat works through a matrix that combined friendly firepower with number of targets. Cross reference your total naval strength with the number of enemy ships and you get two numbers: the first indicating how many dice you roll and the second telling you which number chart to roll on. The higher the numbered chart the more it is filled with possible results that cause harm to the opponent. Rolling several times allows you to accumulate results. They are separated into columns affecting the different categories of naval units in WiF 5th Edition: light surface ships, surface capital ships and carriers. Transports can only be hit if you “overlap” and manage to hit all other escorts first. Submarines have a different combat phase entirely and aren’t involved in the usual naval battles. They can still attempt to intercept and shoot at enemy forces causing trouble (and of course escorts can fire back)

One difference between air naval combat and surface combat is that the attacker gets to choose which ships get assigned damage when it’s naval air (or surprise) and in surface combat it’s the defender. Naval air combat also adds the anti-air rolls to see if bomber factors get reduced or if entire air units are aborted or destroyed.

It works surprisingly well and removes most of the tactical minutiae from the hands of the player (i.e. you’re not lining up ships and shooting at each other as if you’re fighting Trafalgar or Tsushima). There’s still operational aspects of deciding how much force to send into a sea area and which sea box it goes to, considering the scale it’s on par with the land combat in adding good detail but not too much.

The final edition changed things a bit by introducing the concept of a defense value: in addition to applying the combat result against the ship you rolled a die to see if you applied the result or a lesser one. Though the charts now had the results be generic rather than applying to ship classes. Essentially the defense was transferred from the class to each individual ship per their rating allowing defense to be more granular. The final edition added another sea box while changing the way surprise worked: now you had surprise points instead of a surprise number in the box. These points could be spent to avoid combat, choose the type of combat you wanted or to choose the target (regardless of naval air/surface combat).

Air Power

Air combat can occur in any of the impulses, during naval ones it’s usually because of naval air combat. If it’s a land impulse it’s because of air strikes against enemy ground units or ground support missions. The combined impulse can include air battles over strategic bombing. In all cases the mechanics are the same. Each side lines up their fighters and bombers in whatever order they choose and add up the fighter strength by using the “front” fighter’s air to air strength plus one for each additional fighter behind it (regardless of rating) and 1/2 for each carrier. Note also that carriers can also work as bombers so players must choose how the carrier flies. If you don’t have fighters then you use the air to air strength of the front bomber (only).

The air combat table is a differential table so you roll two dice on the appropriate column yielding results that may damage enemy air units, clear the front bomber. This is perhaps the most clunky of the combat systems and can last multiple rounds depending on the size of the air fight. I would have rather had something more akin to the naval system without having to decide if a carrier was committing fighters or bombers. For my taste, this mechanism is a little bit too fiddly for what it is. I can appreciate though that the system allows for bombers to attempt to fight their way to enemy targets since CAP isn’t perfect by any means.

Grinding your Gears

Most strategic wargames of this scope introduce a production system of some kind. A way to put land, air and sea forces on the map to fight for global domination. Third Reich and its successors have points called BRPs (pronounced “burps”) and you spend them to buy whatever is in your force pool and put them on the map or (if it’s a unit that needs more time to build) on a track to come in a later turn. Other than what was in your force pool and the available number of points there aren’t any limits on what you can purchase. Pieces are added to your force pool usually by a schedule dictated by the scenario or via a mechanism called mobilization that let’s spend a different set of points to add pieces to the force pool. In WWII European Theater of Operations and its pacific counterpart there are similar production mechanics and their points are called EPs. Units are added to the force pool via a fixed schedule. Axis Empires uses cards to control the force pool and replacements (air and naval forces are abstracted and are “spent” on the map and return automatically after a number of turns with modifiers).

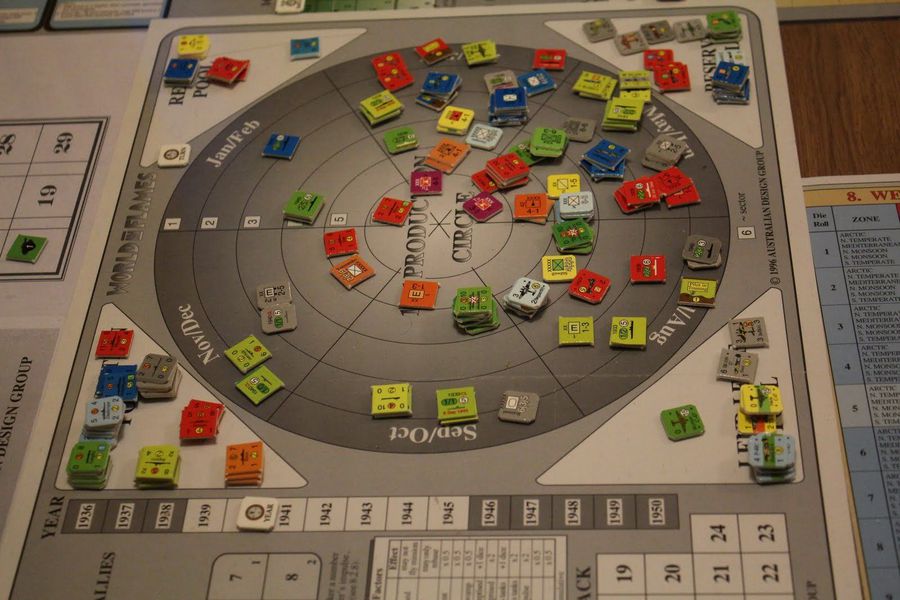

WiF has something called Gearing Limits. This is partially what sets this game apart from its peers in that you can’t just build whatever you want from turn to turn. In those other games production tends to be a seasonal thing, something that happens in the lull between operations. Not WiF, turns are two months long and production occurs every turn. The points used in this game are BPs (Build Points), which are generated by combining points generated from factories (PPs, Production Points) one to one with resources you own and transport to the factories (RPs, Resource Points). Then you can build units but you’re only allowed to build one of each unit per game turn. That sounds very limiting but here is where gearing limits come in: next turn, you can build one of each type of unit plus whatever you built last turn.

This means that on Jan-Feb 1941 if you built 1 infantry unit, on Mar-Apr 1943 you could build 2, then on May-Jun 1941 you could build 3, and so on. In other words, you can’t suddenly decide to build a bunch of airplanes one turn and then switch to tanks in the next turn followed by a half dozen ships in the following month. Building out your force pool requires some thought and planning to make sure you’re supplying your forces with what they need and not suffer a sudden shortfall. Like the other games some units get added to your force pool during specific calendar years (beginning with the Jan-Feb turn of that year).

Diplomacy

For the most part the sides are fairly well defined. Italy, Japan and Germany will always be the Axis of Evil. Russia, France, Britain, China and the U.S. will always be on the same side. That said, depending on the scenario some powers will be neutral and others will start at war. There are a host of rules controlling how and when they can declare war.

The situations cover limited war by Russia and Japan. Vichy France, its formation, which colonies go Vichy and which go Free French and splitting its force pool. Italy and when it can declare war, and some minor neutrals that happen to own real estate on both maps (Portugal and Netherlands). Finland, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria will always join the Nazis and Germany has some rules to follow on when it can activate these nations to its cause.

In the first few incarnations of WiF, Britain can attempt to persuade Yugoslavia to the allied cause while Germany can rustle up trouble in Iraq. Otherwise, if you wanted some neutral piece of real estate (Spain to get to Gibraltar, Turkey to get into Europe or the Middle East) you had to do it the old fashion way: declaring war.

In the 5th edition the Major Powers can play a little cat & mouse with other minor country neutrals but it costs precious build points and you need an established presence in the form of a cell to launch a coup. Cells are set up in the 1939 scenarios and are fixed in place. You never add more and never move them. They are secret, so these are one time firecrackers and it’s possible you picked to put a cell in a country the other side put one too in which case they can cancel your coup. Fun stuff! As far as I can tell, this was taken out of the final edition.

The U.S. Starts the game as a neutral power and it probably has the most complex set of mechanics that govern its behavior as a neutral. It has a track that measures how far along the U.S. has geared up for war and whether the political climate is ready to declare war.

In the first few editions this track was impacted by the behavior of the other powers: the more aggressive the Axis powers behave (especially Japan) the faster the U.S. slides towards war, conversely if the Allies engaged in aggression this would slow U.S. At the same time, the U.S will have options open up that it can select to enable actions that otherwise neutral powers can’t engage in. For example:

- Lending resources

- Escorting Convoys

- Building Chinese aircraft

- Reinforcing the Philippines

- Building & Repairing Allied ships

That’s just to name a few. And some of these actions can slow U.S entry into the war. Up till the 4th edition this track was just a number the U.S kept track of in its build sheet but was fairly easy to keep track of with the Axis/Allies gaming their behavior to min/max the system. 5th Edition introduced more variability and secrecy by drawing U.S entry chits with values in them. Meaning the Axis could no longer be sure what the current U.S score was with certainty (but could more or less estimate it based on U.S entry option choices). This provided uncertainty for the access and they could no longer time with precision U.S entry into the war. The final edition kept this system and polished the U.S. entry options.

Victory at any Cost

The game’s victory conditions center around geographical objectives, essentially certain cities in Europe and the Pacific (or islands as the case may be). There is an automatic victory centered around controlling a subset of these objectives. As you can guess, that doesn’t happen very easily. The first four editions divided these objectives into groups with different VP values for the Axis and Allies. The scenarios had each side pick an objective group (including possibly a strategic objective group which was all about controlling, factories and resources) and they would score the modified value for picking a group at the end of the game. If both sides picked the same group then the scores would double. There were two victory checks: one at the end of Nov/Dec 1944 that didn’t score the secret objective groups and the Jul/Aug 1945 that tallied the modified VP instead of normal VP.

If this sounds overly complicated, Harry Rowland agrees with you. In the 5th edition the objective groups were dropped. You had a total of 20 objective locations in each map. Automatic Victory came if you reduced the opposing side to 2 or less objective cities. If the Allies couldn’t clinch and automatic victory by the last turn of the game the Axis won a sort of moral victory. The final edition had more maps, more cities and more locations so there a total of 11 automatic victory cities and a grand total of 67 locations for the taking. You could bid for each Major Power you controlled and subtracted the bid from the total objectives you controlled by the end of the game.

The edition I grew up with had four scenarios: 2 one map scenarios (for playing just Europe or the Pacific, plus 2 global scenarios; one set in 1939 and one set in Nov/Dec 1941. Later editions added a couple of one map, five turn introductory scenarios. The first centered on Barbarossa, and the second in the Pacific around the time of the battles of the Coral Sea and Midway. More global scenarios were added to begin the game in May/Jun 1941, July 1943 or May/Jun 1944. The final edition had a similar set of scenarios (adapting one map games to two map games, and two map games to four map games) but also added a Jul/Aug 1940 scenario to skip the fall of France. This allowed players to tailor their desired gaming experience by choosing their starting points for a global war.

The End of the Beginning

How does this game play? Overall I’d say very well despite the little quirks and sometimes clunky mechanisms. Things do tend to move along with a great deal of action in the summer months with plentiful impulses and less action during bad monsoons and brutal winters. Each sub-system is its own thing but still feels remarkably well integrated into the production and operational engine.

You never feel like you have plenty of resources to do everything you want. You face hard choices in building more aircraft or more tanks? more bombers or more ships? Perhaps only the Russians have their production priorities relatively simplified because they’re fighting a major land war that requires a lot of infantry, tanks and aircraft. At the same time they tend to be the poorest of the Major allies in production and resources and really need lend-lease that often means they don’t get build every last tank and airplane they want to.

Once you get stuff on the map you have to execute your plan and destroy the enemy forces, control the seas to take the bases that will allow to capture and hold the necessary victory objectives. These dovetail nicely with conquering the enemy but focus too much on map and you may end up losing the game on the other. Overall an engrossing experience that tells a fairly good World War II narrative. This game always felt on the edge of adding just enough chrome without feeling overwhelming (I speak of course of the classic edition without adding all the extra maps, planes, ships, divisions, pilots, mechs and so on that turn World in Flames into something more akin to SPI/Decision’s War in the Pacific).

I played this game to death during high school and formed my early understanding of wargaming World War II. Naturally, I didn’t stop there, as I discovered more titles (Third Reich, SPI/TSR World War II: European Theater of Operations to name but two) I expanded my horizon and enjoyed a lot more gaming goodness. World in Flames marked the end of the beginning for me as a wargamer.

Coda

They say books aren’t finished only published. So it is with wargames, but even more so since if we’re lucky we get a designer to revisit an old game, polish it a bit and provide some extra fluff to play around with making the old new again. In the case of a venerable franchise like this one, we get expansions, editions and iterations successively growing and expanding the game. I would argue that Harry Rowland actually spent 30 plus years designing World in Flames but decided to publish each iteration and benefit from a lot of feedback as he went along rather than wait 10-15 years before finally being satisfied with his vision.

Evidence that the road has more or less reached its end is the proclamation of the final edition with its four map ensemble, a classic edition which while still a monster game is still 1,400 counters (the original game started at 1,000 before 5th edition added another 200). The Collector’s edition is virtually the same as the final edition but with much nicer looking mounted maps and production boards. Not to mention finally changing the Commonwealth armed forces from the hard to see dark blue background to a much nicer khaki. After all is said and done World in Flames has evolved into a fine wargame with lots of entertainment value that I have grown to appreciate as it reaches middle age. If you haven’t checked this game yet you’re missing out on one the hobby’s most interesting gaming experiences. Just make sure you have a large dining table.

-Francisco

Great paper! Hope that some day Alexander and Grant could steer away from Monopoli-like stuff and finally merge into real wargaming

LikeLike

Lol, and give up their lives, jobs and families to play it.

LikeLike

Matrix Games has a PC version, with 3 hardback books and a world map that can cover a wall in your house. I believe it is never ending work in progress though.

LikeLike

The Matrix version has useful tutorials for the absolute beginner; on this count, it is a well-advised pick. Admittedly, though, it is out-dated, for the (nearly) most recent version, i.e., the WiF Collector’s Edition Deluxe Game has by and large superseded (for better or worse) the previous editions. Wiffers, do please stick to the Fifth, please do! (trust an out-and-out Wiffer…)

LikeLike

Wonderful article, but I believe you made a mistake here:

“… this is done via a die roll check after each 2nd impulse (guaranteeing that each side, Axis & Allies, get the same number of impulses)”

The rules have you role to end the action stage every impulse:

“D2.4 End of action

Roll to end the action stage. If it doesn’t end, advance the impulse marker the number of spaces shown on the weather chart for the current weather roll. If it ends, move on to stage E – the end of turn.

D3 Second side’s impulse

If the action stage didn’t end, repeat the steps in D2…”

Perhaps older versions played the way you mention? I’m extremely new to the game (so new that I’m actually playing Fatal Alliances as an on-ramp. Though, I DO have my Deluxe Collectors Edition punched and ready!)

LikeLike

(Also they aren’t chosen by theater)

Ok, I’m gonna stop being That Guy now.

LikeLike

Hi Joe! Thanks for the kind words! I’ll double check because multiple editions did things differently. 2nd Edition I believe rolled every 2nd impulse so each side had the same number of impulses.

LikeLike

Yeah I wasn’t trying to criticize. This article made me more excited than ever to get to WiF.

I just wanted to offer a possible correction.

The setup now has it that the first two pairs of impulses are guaranteed, and then the rolls can end the action stage every impulse.

So everybody goes twice, but then it’s up in the air!

An interesting thing is that if the same side goes first and last in a turn, the initiative marker moves away from them.

A booby prize for the side that didn’t get to go.

(This is a possible reason why the side that won initiative might choose to go second. They may want to move the initiative marker toward their side so they can go first in a later turn. (Odd how often that happens. It’s the example the book gives, anyway.))

LikeLike

Thx for sharing. Great

I planned to go China, but suspended by the coronavirus, so can only learn Chinese at home and took the live online lesson from eChineseLearning

Do you think this method of learning is realistic?

LikeLike