I love asymmetrical wargames, especially those that are designed by Volko Ruhnke. Some of my favorite designs that he has graced us with are Labyrinth: The War on Terror, 2001-?, Wilderness War, Fire in the Lake: Insurgency in Vietnam and Falling Sky: The Gallic Revolt Against Caesar. He has though taken a step back in history with his last two designs (Falling Sky and its expansion Ariovistus) and focused more on the ancients and now he is taking a stroll into the Medieval period with his latest design Nevsky: Teutons and Rus in Collision, 1240-1242 from GMT Games. While at Origins 2018, we met up with Wendell Albright who is serving as the developer of this game and he gave us a quick intro to the system and I could immediately see that this was destined to be a good game. I immediately contacted Volko and just had to ask him nearly 35 questions on the design. As usual, Volko was extremely gracious and gave me the following answers for you to read through and come to understand whether Nevsky is a game for you.

Please keep in mind that the materials used in this interview of the components, maps, player boards and card are not yet finalized and are only for playtest purposes at this point. Also, as the game is still in development, details about the game may still change prior to publication.

Grant: It seems you have taken a step back in time for your last few game designs, including Falling Sky and it’s expansion Ariovistus and now into the Medieval age with Nevsky. Is this a trend now reflecting your tastes or is it just what’s for dinner tonight?

Volko: It’s a local trend of backing away from topics that are too close to work, as I have eased psychologically into retirement. But it is more the latter: I have always been a tourist wargamer. I mainly want games to transport me to times and places that are new to me. I have the same wanderlust for design. Having recently visited the Ancient World and then the first millenium AD via COIN, the hankering to fill a yawning gap of centuries across the Middle Ages was a big part of my spur toward Nevsky.

Grant: What do you find compelling about the Medieval period that led to your interest in designing a game around one corner of that period?

Volko: Starting with the gap in wargamer attention to the era, the most compelling aspect is the wealth of stories there, yet to be told in our medium. We call it the feudal system for a reason: feuding was near constant, warfare and trial by combat so central to politics and society, that we have a remarkably rich military history to explore as hobbyists.

At the same time, the nature of warfare may strike us as unusual and exotic, perhaps even more so than that of the classical era centuries more distant from our time. The early Medieval period (or Dark Ages) saw a rebuilding of society including military culture from the wreck of the Roman Empire. The high Middle Ages developed that shaky reboot into its own new form that continued for centuries before development into modern professional military practice. This is a long and twisting road that bears detailed examination and simulation well beyond the comparative handful of wargames on medieval topics, particularly at operational scale.

Grant: Why did you choose Nevsky and the Teutons versus the Rus? What is so interesting about this period?

Grant: Why did you choose Nevsky and the Teutons versus the Rus? What is so interesting about this period?

Volko: With so much Medieval action to choose from, I am most eager to visit the most consequential and diverse spots. Just as the boundary of ecosystems tends to host the richest and most varied forms of life, so warfare at the frontiers, at cultural boundaries, tells the most engaging stories. Replaying which German baron will rule a certain Burg for the next several years may be interesting, but how much more interesting to re-fight the campaigns that set borders between Russia and the West that survive unaltered to this day!

That’s consequence. And with cultural as well as straight military clash, we also get diversity—fascinating asymmetrical contests, such as Teutonic Order versus Novgorod republic, warrior monks against princely druzhina, cogs and lodya, trebuchets and perhaps even horse archers from the distant steppe.

Grant: Do you have some recommended books on this subject that you used as reference?

Volko: It should not surprise us, in light of the more limited contemporary sources for the Middle Ages than for 20th Century topics, that so many apparently basic conclusions about Medieval warfare or any given campaign might be controversial. Historians disagree a great deal about who and what was most important on a Medieval campaign and how things went down in 1240-1242 in particular. Was the Teutons’ impulse religious or pragmatic? How far and frequent was the participation of the Danes? How great was Aleksandr anyway? Did the battles involved thousands or merely hundreds on a side? Did Aleksandr employ Mongols?

I have tried to read as widely as I could in the English language. But I have already gotten into trouble in wargamer quarters more expert than I on issues such as the degree of asymmetry between Russian and Western medieval military technology, the possibility of Asiatic horse at the Battle of the Ice, or the uses and impact of carts relative to boats in medieval Baltic warfare. (The feedback has been most helpful to the design, though I don’t for a moment expect to satisfy everyone!)

Here is my bibliography for Nevsky, as of now, with a bit of summation:

Warfare on the Baltic Frontier

Christiansen, Eric. The Northern Crusades (1997 Second Edition of 1980 original). Rich in  cultural and economic description of the Teutonic sweep into a Baltic region of diverse pagan and Russian peoples, including the roles of popes and legates and some pages on the crusade against Novgorod.

cultural and economic description of the Teutonic sweep into a Baltic region of diverse pagan and Russian peoples, including the roles of popes and legates and some pages on the crusade against Novgorod.

Nicolle, David. Lake Peipus 1242—Battle of the Ice (1996). The most detailed discussion in English of the particular campaign covered in the game, albeit full of controversial interpretations such as a timeline at odds with the Novgorod Chronicle, a larger role for the Danes than some other historians accept, and the depiction of Mongol or Kipchak horse archers in Nevsky’s 1242 army.

Selart, Anti. Livonia, Rus’ and the Baltic Crusades in the Thirteenth Century (2007). The academic view from Tartu (once Dorpat), with deep probing of the nature of Teuton-on-Rus conflict, generally downplaying its scale and importance within the larger fabric of an economically and culturally interwoven region.

Urban, William. The Teutonic Knights—A Military History (2003). Focused on the German Order’s conquest of pagans, with rather more on Prussia than Livonia, but with useful discussion of the Teutons’ 1240-1242 attempt at conquest of Novgorod.

Urban, William. The Teutonic Knights—A Military History (2003). Focused on the German Order’s conquest of pagans, with rather more on Prussia than Livonia, but with useful discussion of the Teutons’ 1240-1242 attempt at conquest of Novgorod.

Villads Jensen, Kurt, “Bigger and Better: Arms Race and Change in War Technology in the Baltic in the Early Thirteenth Century”, and Mäesalu, Ain, “Mechanical Artillery and Warfare in the Chronicle of Henry”, in Crusading and Chronicle Writing on the Medieval Baltic Frontier—A Companion to the Chronicle of Henry of Livonia (2011). These two essays examine the Teutons’ military state of the art in the period immediately preceding the war with Rus, including a contention that the Livonian crusaders benefitted from a medieval military revolution of the early 13th Century in the size of horses, siege equipment, and ships.

Medieval Russia

Fennell, John. The Crisis of Medieval Russia 1200-1304 (2014 printing of 1983 original).  Move and countermove across the decades, as the great houses of Rus—in true feudal fashion—bickered, postured, and sometimes fought, until the Mongols arrived and mostly ruined them; essential context for the relationship between the Vladimir’s Grand Prince and his sons Aleksandr and Andrey on the one hand and the untouched but militarily dependent Novgorod on the other.

Move and countermove across the decades, as the great houses of Rus—in true feudal fashion—bickered, postured, and sometimes fought, until the Mongols arrived and mostly ruined them; essential context for the relationship between the Vladimir’s Grand Prince and his sons Aleksandr and Andrey on the one hand and the untouched but militarily dependent Novgorod on the other.

Michell, Robert and Nevill Forbes, translators. The Chronicle of Novgorod 1016-1471 (1914). The near contemporary source most frequently quoted by historians of the 1240-1242 campaign, providing in conjunction with the Livonian Rhymed Chronicle some description corroborated from both sides.

Nicolle, David and Angus McBride. Armies of Medieval Russia 750-1250 (1999). Some details on Russian medieval forces’ organization and equipment, though with more on the Kievan period than on Novgorod and Aleksandr’s day.

Paul, Michael C. “Secular Power and the Archbishops of Novgorod before the Muscovite Conquest”, in Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History, Vol8, No2 (2007). Scholarly look at Novgorod’s particular form of rule, with a focus on the political, administrative, and diplomatic roles of the archbishops there, with useful contrast to the warrior-prince-bishop model in the West.

General Medieval Military Operations

Delbrück, Hans. History of the Art of War within the Framework of Political History, Volume III—Medieval Warfare (1923). The relevant portion of a sort of bible for wargame designers dealing with pre-20th Century military operations, herein analysis of the rise of knights out of the Roman collapse, the 40-day feudal obligation and its blending into mercenary and finally professional soldiery, and much more as the scholar seeks to glean what can be learned from key battles along the way.

France, John. Western Warfare in the Age of the Crusades, 1000-1300 (1999). A more modern version of Delbrückian systemic analysis of medieval warfare: higher political authority, horse and foot, castle and siege, campaign and command, ravaging and supply.

France, John. Western Warfare in the Age of the Crusades, 1000-1300 (1999). A more modern version of Delbrückian systemic analysis of medieval warfare: higher political authority, horse and foot, castle and siege, campaign and command, ravaging and supply.

Keen, Maurice, ed. Medieval Warfare—A History (1999). A collection of essays providing reinforcing assessments of the nature of medieval campaigns and military technology, with details such as the particular challenge of keeping large numbers of heavy horses fed, to name just one.

Oman, C.W.C. The Art of War in the Middle Ages (1885). Brief, readable, fundamental essay on the nature of medieval warfare, later deemed to overemphasize the role of the heavy knight in obtaining decision on the battlefield.

Verbruggen, J.F. The Art of Warfare in Western Europe During the Middle Ages (1997). The most influential 20th-Century work on the general topic; a corrective to or at least elaboration of Delbrück and Oman regarding, for example, the supremacy of the armored horseman, Verbruggen gave more examination to the impact of a combined arms system of elite cavalry, numerous pike-armed foot soldiers, and supporting archers.

Grant: What challenges and opportunities did you find in this design?

Volko: A key challenge has been to turn my own views of feudal politics and Medieval logistics into a game that boardgamers who don’t happen to start with any particular fascination with this more obscure subject will find easy and attractive to play, while also presenting a model that is credible enough for passionate specialists to accept as a worthwhile throw at simulation.

The opportunities are many and interlocking. I have been hankering to get back after so many COIN Series projects to some meatier, two-player wargaming; I have always wanted to provide more satisfying and explicit logistical play than in my earlier designs; I have been looking for a place to exploit Ragnar/MMP Angola’s brilliant column card mechanic; and I have since an undergrad course on English constitutional history wanted to test out the impact of time-limited feudal obligations on a military campaign. So Nevsky scratches a rash of itches for me!

Grant: I know that this game is the inaugural title in the Levy & Campaign Series. What qualifies a game to be included in the series?

Volko: My sense from conversations with Gene Billingsley is that Levy & Campaign offers a system that could efficiently portray military operations in a variety of pre-industrial contexts, including ancient tribal warfare, the Dark Ages, the Renaissance—any campaigns for which limited service obligations by troops had an impact. I had originally conceived of the system as the Medieval Campaign Series, but Gene opened my mind to the larger possibilities.

So the best and first answer is, “who knows?” Of my original idea for four volumes in the COIN Series, only the first idea has seen publication. Where will L&C end up venturing, if it succeeds in any similar way?

To qualify, a setting must offer something new to the Series’ examination of pre-industrial operations. Perhaps that it different kinds of troops, or a different political structure that mobilizes the forces, or different logistical techniques and technology. But that criterion leaves a lot of room to roam!

Grant: What other topics or conflicts might eventually find their way under this banner? Have you already started scratching out notes, mechanics or special elements for any specific one?

Volko: My plan, which may or may not survive contact, is for four volumes in the Levy & Campaign Series to visit the four corners of Europe’s Medieval world: Russian, Scotland, Spain, and the Holy Land. Nevsky, Longshanks, El Cid, Saladin—each volume will allow us to explore a different military frontier with its own sexy cultural clash, diverse asymmetries, some new units and capabilities and some old favorites showing up each game.

I have done some early research on each of these settings and have scratched out or at least made mental notes on special elements, and some of the design decisions in Nevsky are in preparation for how the Series will portray these other settings with as much convenient reliance as possible on what I hope by then will be familiar mechanics to Levy & Campaign players.

I also have gotten early nibbles with regard to potential designers who might one day take the Series further afield—to China or Japan, for example.

Grant: What elements are really important to model in this design to address the way battles were fought, armies were created and the logistics of the time?

Volko: As Wendell said in your recent Origins interview that you mention below, there are a lot of moving parts. He laid them out well, and I encourage anyone interested in getting a quick sense of what our model covers to give that video a view. The big subsystems in nested interaction are:

- The Feudal Calendar, governing who might fight when and how long;

- The Levy of Lords, Vassal Forces, Transport, and special Capabilities to join in the Campaign;

- Logistics, including the Supply and movement of Provender across various Ways in a variety of Seasons; and

- The contest of various Forces and Fortifications in Siege, Storm, and Battle.

Grant: As you mentioned, I was able to meet up with the game’s developer Wendell Albright at Origins and get a sneak peek into the game. What skills and experience does Wendell bring to the table and how have his efforts affected the design to this point?

Volko: As one of his handles, WIFWendell, suggests, he is a World in Flames aficionado, so experienced and adept at hardcore tabletop military simulation. Levy & Campaign is rather more wargamey than my COIN Series designs, so I needed a developer who would be highly competent and comfortable in that genre.

As his other handle, WickedWendell, might imply, he is exacting as a critic and as an editor, and you will have no trouble accepting that such wickedness is the fuel of greatness for the development of any designer’s pet into a market-ready machine.

The way that these traits have played out in development is that Wendell has taken all the playtester feedback—no need for anyone to fret about Volko’s feelings—and brought me in his voice the nature of issues to be solved. I then ask him, what does he think about fixing it this way or that way, to give me confidence that the change is an improvement for both historicity and gameplay. And thus we have changed the design—A LOT, from core sequence to individual event cards, again and again.

Grant: Let’s talk about the feudal calendar and the logic behind it. How does it work in the design? What limits does it place on players plans? What is the reasoning for it being broken into 40 day periods?

Volko: The 40-Day Campaign turns in the Levy & Campaign Series come from 40 days as the basic and traditional feudal obligation of military service (see, for example, Delbrück, page 102). I remembered that number from my undergrad history class, as raising the question in my mind, how must that rule have impacted warfare, if suddenly on campaign or during a siege, a group of knights and their sergeants, men-at-arms, blacksmiths and cart-drivers told their commander, “that’s it, milord, our time’s up—we’re heading home”!

The Calendar in the game integrates that temporal aspect of Medieval operations—Service obligation—with all the other aspects, such as who could Levy whom or what to service, how long did it take to gather a force and move it into enemy territory, what was the effect of silver coin or looted booty or battlefield success on noble warriors’ morale, and so on.

The Calendar, which occupies about a third of the 17×22-inch game board, tracks each Lord’s Service obligation with a marker that is placed as the Lord Musters and slides back and forth depending on what happens to him. If the current turn hits a Lord’s marker, his time is up and he Disbands, perhaps only for a pause of a Season or more, until Levied again.

There is quite a bit more to it, but it seems easy enough to execute and leads to some tasty dilemmas. Your readers can get a fuller idea of Nevsky’s Feudal Calendar in this InsideGMT post (plus of the other big subsystems in later posts), here: http://www.insidegmt.com/?p=20237 .

Grant: How can players keep their armies in the field longer? What must they be aware of when these decisions confront them?

Volko: If anyone checks the Delbrück reference above, they will read that ostensibly feudal armies very quickly became mercenary armies in effect. The Feudal system in large measure reflected the fact that not much money was in circulation, and that wealth was tied up in land and livestock, and direct control of land meant power. But there was money too; silver pennies circulated on the Baltic frontier before and during our period, for example. If your Lords reach the end of their formal obligation in your army, you can always pay them and their Vassals to remain longer—if you have the Coin. Each Coin counter spent will push one Service marker by one turn (40 days) further into the future.

Then, potentially even better, there is Loot. So much of medieval warfare was raiding: Ravaging enemy territory to bring your adversary to terms, but also to reward your friends. In the game, Ravage actions gain you not only victory points but also Provender and Loot. If you can drag and herd that Loot back to your own base—friendly territory or a Castle you may have Conquered or built on the enemy’s land—you can dole that Loot out to your Lords and Vassals to buck them up for more, even more effectively that a relative pittance of Coin you may be carrying. A single Loot counter can extend the Service of all Lords and Vassals involved out by 40 days each.

But all that is harder than it sounds, because so many difficulties might intervene to force your Lords’ spirits in the opposite direction. Lack of Provender, loss of a Battle, Surrender under Siege, and a variety of unexpected external Events might lead your Lords to renege on their agreed Service, sliding their markers on the Calendar back toward the present. If a Lord ever faces a Disband check while his Service marker is to the left of the current turn, that Lord has served beyond his perceived obligation and opts out of the war for good!

Grant: I see a big part of the game as involving planning. What must players plan for in order to have successful campaigns? What elements will trip them up if not planned for?

Volko: That’s right—planning hindered, naturally, by the uncertainties of the campaign to unfold!

Every 40 Days, each side will use Levy by Lords and sometimes Call to Arms by higher authorities to Muster people and equipment that they think they will need. Lordship is limited while possibilities of what to gather are wide. Players will need carefully to weigh and wager what might become necessary this turn.

Then both sides will Plan their Campaign—array a limited number of Command cards in a stack, locking in their desired order in which those Lords they select will undertake actions in the coming Campaign. (See the discussion of Command cards below.) Of course, neither side at this time knows what the other side’s Plan is, nor what the other’s Lords will undertake.

Grant: Another part of the design involves logistics. How did you capture the struggles of keeping armies fed, supplied and clothed?

Volko: Logistics in Nevsky focus on Provender: mostly food and fodder, but also other consumable necessities of medieval warfare such as smithing supplies, crossbow bolts, and so on. (Note, just as an interesting comparison, that Hollandspiele’s Tom Russell, in his innovative Supply Lines games about logistics in the American Revolution, required two types of supplies—Food and War Supplies—because powder and shot become major concerns once guns enter the scene.)

Lords must Feed their Forces at the end of each Command card that they move or fight. If they are performing less stressing or more sedentary activities, or actions that themselves gather Provender, or perhaps nothing at all, the troops are considered to be seeing to their own needs locally for that time. Note that, if the Lord of one side Attacks an enemy—or merely presses him to back away from a potential Battle or works on tightening a Siege—the enemy Lord also has moved or Fought. Thus, a starvation strategy is available to the side that has an advantage in Provender.

Obtaining Provender itself requires Command Actions, typically calling for certain Transport to haul supplies up to the Lord’s Locale. And taking Provender with you as you March will require sufficient Transport also, if the Provender is not to cut a Lord’s March pace in half. And in the case of insufficient Transport, a successful Attacker will snatch away whatever Provender a Defender cannot move by Transport.

Therefore, Lords will need to Levy the right amount of Transport or risk starving their army. And any army that is starving will tend to turn for home: each occasion that a Lord is to Feed his troops but has insufficient Provender or Loot to do so, that Lord’s Service is shortened by 40 days.

To see more about keeping armies fed in Nevsky, see part 2 of the InsideGMT series detailing the game’s mechanics, here: http://www.insidegmt.com/?p=20513 .

Grant: Sleds, carts and boats means lots of ways to move goods. How are each important in the game and when are they useful and not so much? Also, weather impacts the Eastern Front I see but in a different way. How did weather effect Medieval armies in the east?

Volko: Medieval operations had to match the rhythm of the Seasons. Interestingly, the particularly long and harsh winters of Russia did not mean campaigning ended. On the contrary, the frozen ground and water meant that movement across marshland became easier, for example. Armies used sleds in place of the wagons of summer.

But then everything melts, and we have the Rasputitsa mud familiar to WWII East Front gamers. Medieval warfare does not end with the great thaw, but it does bog down along key Ways, even while the rivers and seas open up and the days get longer. Now Boats and Ships come into play. Great river networks were the key to Russian trade and military movement, so Boats can provide quick speedy movement across the game map, for example, and Ships Supply grain from off-map—across the Baltic for the Teutons or from the Asian interior for the Russians.

While roads (or, more likely, trackways) were sparse, Waterways relied on portages over land. So there is also advantage, once Summer brings dry ground, to obtaining a train of Carts. Carts in the game represent not just single-axel vehicles but wagons and pack animals—whatever might haul Provender overland. Carts will work only in Summer—just one fourth of the game—but Summer also features the longest days and best weather, in the game, the most Command cards as well as the ability to Forage. Carts, then, may be worthwhile even for that single Season, for all the hay to be made!

Grant: I also understand that armies can Ravage areas or Forage for food. How are these two actions different? Did the idea of Ravaging have its genesis in your previous Wilderness War design?

Volko: Forage in Nevsky represents gathering supplies off the local land as needed to sustain the army, rather than anything punitive. In fact, once a Locale is Ravaged, no more Forage is available there! Forage in the game simply provides one Provender from any un-Ravaged Locale—but only during Summer, when there is plenty of grain around.

Ravage is bent on destruction: the point is to inflict pain on the rulers of the Ravaged territory. Goods are taken during the burning, of course, but they are incidental to the strategic purpose. In the game, only enemy territory may be Ravaged, but in any Season, earning ½ VP and one Provender plus one Loot (which can be used to reward and encourage your Lords).

The genesis of Ravaging in Nevsky is in the nature of Medieval campaigns as described in the historical works listed above—raiding was a major part of war. But, yes, I did refer to my experience with Wilderness War’s Raiding action and Raid markers—players of Wilderness War will notice the similarity there to Ravage in Nevsky, such as the placement of ½VP markers, as well as lesser similarities between the two designs in the use of rivers and in their Siege subsystems.

Grant: What types of asymmetry are built into the design and how specifically do the Teutons differ from the Rus?

Starting with the tactical level, the differences are not stark, but there are indeed asymmetries. For example, both sides have elite armored horsemen, but the professional standing druzhina of Russian princes is typically described as small in number, while the Latin crusading orders were able to mobilize substantial numbers of knights, if only seasonally. Both sides have archers, with crossbowmen more prevalent on the Teutonic side and archers more numerous in general in the Russian armies. Both sides possess siegecraft, but the Teutons have advantages in more and stronger stone wall Fortifications. At the most exotic, the Russians may field Asiatic horse archers—Steppe Warriors—but only if the Russian player makes the effort to obtain them, giving up something else.

At least as importantly, the structure of the Teutonic Lords and Higher Authority and those of the Russians differ markedly. For example, the Teutons have a variety of potent Lords at the ready, and can call upon a second Marshal—a Lord adept at leading several others—if their first runs into trouble. The Russians, meanwhile, start most scenarios with their best princes—and their only Marshals, Aleksandr and his brother Andrey—unready to Muster on account of a political fracas between Novgorod’s veche (city council of notables) and the princes’ father, Grand Prince Yaroslav Vsevolodvich of Vladimir-Suzdal.

Even once Suzdal is willing to send these Lords to help the great city, the veche might decline in order to demonstrate its independence of the Grand Prince. In the game, the Russian player, in the role of Novgorod, can delay Muster of Aleksandr or Andrey in order to earn VP thereby—but risk those Russians at hand getting steamrolled by the oncoming Teutonic Knights. On the other hand, the player will have to expend VP to Levy the great princes, or to do most anything else during the Russian Call to Arms, as any Levy of Lords shows up the city boyars’ military incapacity and dependence on others.

For the Teuton player, a papal Legate, Henry of Modena, may come and go and lend a hand by encouraging or arbitrating a more forceful crusade against the schismatics. But arranging his arrival distracts Lordship from other tasks—he appears via a Capability card that must, in effect, be purchased—and he must personally be on the scene to have an impact: a Legate pawn on the map shows where Henry is, and he can be captured.

These above are just a few of the aspects of feudal relations in the game. I hope players will try the game to explore the rest!

Grant: What is the force structure of the various units comprising the armies? How does each side’s units differ?

Volko: Before we even get to the units, there are considerable differences in the array of Lords on each side—their Fealty, Service, Lordship, and Command ratings; their starting Retinues and Households; the locations of the Seats; which Events and Capabilities might affect them, and so on—far too many to explain here.

The force structure is that either side will have Mustered some number of up to six Lords each, perhaps with help from their Higher Political Authorities. Each Lord will display on a 5-inch square map some starting units and Assets such as Transport, plus markers for Vassals that he might Levy to add more Forces.

Forces divide into Horse and Foot, Armored and Unarmored (see below). Each unit piece represents from 50 to 200 fighting men, though even that range is a low-confidence one, since the numbers are in so much historical dispute.

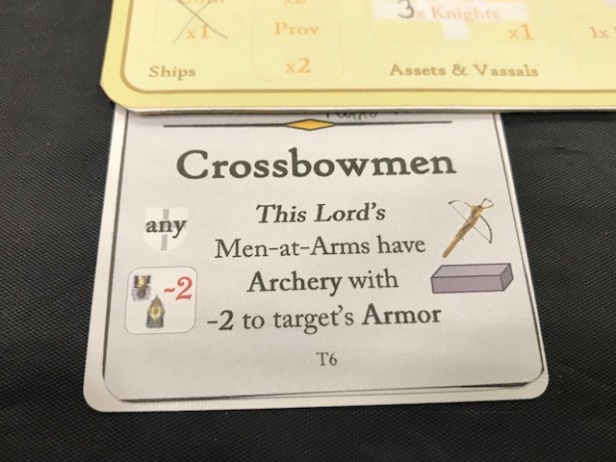

Lords are then augmented in their abilities by various Capabilities that they have Levied or fleeting Events that might occur.

Grant: Are you using counters or wood to represent units? Why did you make this choice? How has it effected the gameplay and immersion by players?

Volko: We have counters for various markers such as Service, Siege, Ships, and the like. But the Lords, their Forces, and a Papal Legate who shows up from time to time are of wood.

One effect on gameplay of using wooden unit pieces is as an enforcer on me: since I can’t associate much information with any given unit type, only what is easily remembered from seeing the shape of the piece, it keeps the combat system quicker and simpler.

One effect on gameplay of using wooden unit pieces is as an enforcer on me: since I can’t associate much information with any given unit type, only what is easily remembered from seeing the shape of the piece, it keeps the combat system quicker and simpler.

With regard to immersion, the use of wood helps me because I can better envision through three-dimensional shapes in appropriate colors the groups of men arrayed on a field than I can with flat counters bearing numbers and images of a single soldier or two each. Medieval cavalry attacked in wedge formation, per Delbruck, while infantry formed rouge phalanxes; so we have wedges for Horse units, brick-shaped blocks for Foot. I have not heard of any complaints in this regard from anyone who has played the game.

With regard to immersion, the use of wood helps me because I can better envision through three-dimensional shapes in appropriate colors the groups of men arrayed on a field than I can with flat counters bearing numbers and images of a single soldier or two each. Medieval cavalry attacked in wedge formation, per Delbruck, while infantry formed rouge phalanxes; so we have wedges for Horse units, brick-shaped blocks for Foot. I have not heard of any complaints in this regard from anyone who has played the game.

Grant: I agree that wood is better and like the idea of the three-dimensional vision of the different type of units. Tell us about the role the Lord Cards Play.

Volko: Each side has three Command cards per Lord that they select to form each Campaign’s Plan stack. During Campaign, players alternate flipping a card and taking actions with the Lord show. It’s simple and quick—lifted from the Column cards mechanic of Ragnar/MMP’s remarkable Angola, where they simulate the confusion at the onset of a civil war.

Here in Nevsky, the stricture of the cards represents poor communications across the countryside once a war council divided, plus iffy obedience within a feudal system that gave subordinate Lords a lot of sway over their own operations.

Grant: As you mentioned a few times above, the game uses Event cards and Capabilities that are found on the same card. How does this work? Why was this your preferred way to deal with cards?

Volko: I tried out similar paired Event/Capability cards in an earlier, unpublished game design on an unrelated topic. They worked well to depict certain tradeoffs between the uncertain chance of a big but momentary benefit and readying a longer-term, strategic capacity. This pairing of Events and Capabilities is only a little bit about simulating explicit historical choices between the top and bottom of any given card, but more about evening out game effects of giving players the high degree of control in shopping from their full deck of goodies. It also gives a fun twist, I think, to each player’s management of that side’s deck and Mustered Capabilities.

Grant: I love multi-use cards and am very intrigued by their use in Nevsky. Can you show us a few examples of the Event/Capability cards and tell us how they work?

Volko: Here’s one.

In this sample playtest Arts of War card, the Event at top and Capability below are mildly related: each represents some aspect of the Russians benefitting from what is going on out in the Baltic, either trade or an island uprising there. The Russian player in considering this card has a choice between exerting effort (Levying) to obtain the Baltic Sea Trade benefit or leaving that on the table for a chance of an Osilian Revolt stinging the Teutons, at no other cost to the Russians.

Grant: How does combat work? How did you go about deciding to assign relative strengths to different unit types? What is the best unit on the field?

Volko: I kept combat straightforward (at least, I hope so), to keep the attention at the operational level. The mechanics are loosely derived from those used in Falling Sky, but with more unit types, differentiation of Melee and Archery, general positioning on the field, and other added aspects. For much more detail on combat in Nevsky, please see my articles on InsideGMT, especially Part 3 and those that will follow, here: http://www.insidegmt.com/?p=20619 .

There is a good amount of discussion in the historiography about the importance and decisiveness of the various combat arms in medieval warfare. So at this very general level—all standard mostly unarmored Foot lumped into a “Militia” type, for instance—it is not too hard to come up with coarse measures such as 1 Hit per unit versus ½ Hit per unit and obtain satisfying combat outcomes. There we have had to make very little adjustments during testing, though, interestingly, we did just decide to bump down Militia Hits caused from 1 to ½, because the big Russian Militia armies were just too overwhelming, and there was too little incentive to put Unarmored Militia out front to absorb Hits—as the Russians did historically (it is thought) at Peipus—to save Armored units that also do just 1 Hit.

You can probably guess that Knights are both the hardest hitting and toughest units around. In field Battle, they Strike two Hits rather than just one to represent their charge with couched lance. And they enjoy the best protection in the game—brushing off Hits and Loss checks on rolls of 1-4 on six-sided dice—representing both their high-quality Armor and their training and zeal.

Grant: How do sieges work? What elements did you feel most important to include in the design? How does it compare to say siege in Wilderness War?

Volko: Lords who are Attacked and/or defeated in the field when they have a friendly Fortification behind them benefit from Withdrawing inside rather than Retreating to another Locale. Whether or not an enemy has Withdrawn inside, an enemy approaching a Fortification, such as a Castle or walled City, immediately gets a Siege marker on the Fortification.

Subsequent Siege actions, under the right conditions, can add more Siege markers—representing the construction of Siegeworks and implements such as trenches, mines, ladders, and so on. Siege can starve out Besieged Lords and force Surrender of the garrison. But if Storming the place becomes necessary, those Siege markers are essential: they both provide protection to the Attackers and determine how many Rounds a Storm may go.

Protection from Walls or Siegeworks is shown in a very similar way to Armor: a die roll range that cancels Hits. Stonework Castles have Walls 1-3, while mostly wooden Forts have 1-2, for example. Each Siege marker adds to the Walls for the Attacker: three markers are Walls 1-3, etc.

Again, please see also the InsideGMT series on Nevsky, which illustrates all these aspects blow by blow!

Grant: Why did you choose point to point movement for the design? How does this create a setting that matches the travel issues of the time?

Volko: Area movement works best for placement-oriented games at a strategic scale, while hex grid is necessary for tactical scale or continuous-front situations. Point-to-point works simply and effectively for maneuver of pre-industrial armies along key ways such as trade routes, valleys, rivers.

In particular, a point-to-point map makes it easy to show the difference between rivers and roads as highways. In Nevsky, for example, longer connections for rivers mean faster movement across the map. So we are showing that sailboats are faster than draft animals, without any special rules. You generally can get between two points in fewer moves along Waterway than Roadway on the Nevsky map—that is, if there happens to be a Waterway in the direction that you want to move!

Grant: The map, as seen above, is interesting. Who is the artist and how does his style effect the game?

Volko: Hah, thanks! We have no official map artist yet – the version that Wendell had at Origins is the lovely rendering from Joel Toppen’s playtest Vassal module. The prototype shown earlier in this interview is by my hand. Wait until we all see what a pro artist can do!

Grant: I actually like the look and feel of the playtest map as it definitely gave me the impression of a period map drawn on a vellum scroll by a Medieval artist. All it is lacking is the statement “Here be dragons!” What have been some changes that have come about through the playtest process? What still needs work?

Volko: There have been many, many changes, from core to periphery—far too much to go into here—and they continue in response to tester feedback even as I write. We are still in alpha test and development. I have even changed the game map many times over recently—both for play effects discovered and as I come across more historical or geographic information. Once the mechanics, card text, and map settle down, we will be ready for beta testing (we hope to identify a few more testers who would be new to the design), and then final balancing of scenarios.

Grant: What are you most pleased about with the design?

Volko: I’m most pleased with the interactions in time and space that the Levy & Campaign Series brings to life via the Calendar, the Levy phase, the geography of the map, and what I hope is straightforward resolution of combat. This larger system in Nevsky seems to produce a coming and going of Lords, maneuvers and sieges, and every now and again decisive battles—all reasonably reproducing the flow of the historical campaign.

Grant: What has been the response of playtesters? How do they feel about the time period now?

Wendell: Playtesters have been enthusiastic about the game; for example the three guys I taught at Origins really liked it. As for the period, most playtesters have said they don’t know much about 13th century Russia! But they all have said part of the appeal is just that – a different era, a different kind of warfare.

Oh and Sleds are da bomb!

Volko: In addition to what Wendell said (and he knows best here, because he is in most direct contact with our official playtest cadre), I have been taken with the number of stories that they have generated from play—always a very good sign! Here’s a peek inside one of their test games:

“Ok, we have a strange situation that just came up in our campaign game. Hermann is alone in Rus-controlled Novgorod (siege marker is placed). Withdrawn inside the walls are the Rus Lords Domash, Aleksander, and Andrey. Gavrilo, acting as Lieutenant over Vladislav, is located in Rusa and marches to Novgorod to initiate battle against the lone Hermann who is thinking . . . ‘I should not be here.’”

“Hermann attempts to Avoid Battle, but the Rus play the ‘Ambush’ card and block him from avoiding the battle. All the Lords within Novgorod Sally out to help crush poor Hermann. Hermann has three ‘Hold’ Events that he decides to play: Ford, Hill, and Field Organ. He would also like to Concede that Battle thinking that the ‘Ford’ Event might allow him to escape relatively unscathed (especially factoring in the +1 armor from Field Organ).”

“So we array for Battle and Hermann is wedged in between 3 Lords on one side (the Sally Lords) and 2 Lords on the other (the active attackers). Hermann opts to Concede the field….”

Now, the testers wrote up this narrative mainly to tee up several questions about mechanics and the card texts concerned, which led to some clarifications. But what a tale, I wish that I had been there!

Grant: What are your expectations for the production of the game based on your experience?

Volko: If you mean timing, I expect that we will be ready for art this Fall, meaning distribution in early 2019. GMT has listed Nevsky for production first half of 2019. Naturally, all sorts of circumstances can change these projections.

If you mean, what are my expectations for the quality of the production, based on my experience with GMT over the past two decades of my designs with them, why, my expectations for Nevsky are sky high!

Thanks for the chance to go into so many aspects of Nevsky!

As always Volko, thank you for your amazingly detailed answers and for the look inside Nevsky. I am going to have to say that after seeing the prototype at Origins (thank you for your time Wendell!), and now this interview, that I have totally changed my mind about the game and am definitely interested.

If you are interested in reserving a copy of Nevsky: Teutons and Rus in Collision, 1240-1242 from GMT Games, you can pre-order a copy at the following link: https://www.gmtgames.com/p-696-nevsky-teutons-and-rus-in-collision-1240-1242.aspx

-Grant

Everything I hear makes me look forward to this even more.

I really think this could be something special if it’s done right, plays well and has value as a historical simulation (something I am still on the fence about with regards to the COIN system).

The levy calendar is genius, the off map army cards showing forces and provisions is another great idea the actions you are able to undertake around movement, pillaging, siege etc all seem pretty accurate. My only concern is perhaps with the ‘column and capability cards’ perhaps being a somewhat gamey way to drive the system.

If this is even half as good as it looks it will provide an incredible series to study and game medieval campaigns.

Something I think has been lacking for the wargame community to this point.

Perhaps due to being a Brit, somethign that sprung to mind for me was how well this system could fit the Anarchy (a period of Anglo-Norman Civil War of 1135 – 1153) a long drawn out seige heavy war containing several smaller campaigns in both England(Britain) and Normandy.

It’s a really great story that seems yet to have beeen told in a wargame, with important leaders from both sides being captured at certain points and nobles switching sides.

Contrary to Volko’s statements about being excited by exploring frontier clashes between differing military/political entities with the system. I actually think that a largely homogeneous nobility able to potentially be levied by either side would make a nice twist on the system.

LikeLike

I agree that this series has some great potential. It will be interesting to see where Volko takes the series, as there are definitely lots of periods and countries to cover. Thanks for reading.

LikeLike

Thanks for the thoughts and the intention to try out Nevsky! re: “I actually think that a largely homogeneous nobility able to potentially be levied by either side would make a nice twist on the system.” … That would indeed be an intriguing twist! I had not thought of that. Best regards, Volko

LikeLike

I am sort of concerned about all the references to Delbruck and Oman. They’re EXTREMELY outdated by now. From the late 1990s and early 2000s on, there has been a revolution of sorts in the study of medieval military history and crusading history. Many older historians have not entirely caught on. And Nicolle sees «asiatic horse» practically everywhere, and is primarily an expert on islamic medieval history. He is very far out of his field on the crusader states. His scandinavian books were complete embarrasments.

LikeLike

Hi! Thank you for the advice! The antidote, I think, is not to refuse to read Delbruck or Oman or Nicolle, but to leaven them with as many other historians as one can access on the topic. At least, that is what I have tried to do, allowing for the likelihood that each historian has something right and other things wrong.

In this respect, a nice feature of games is that they can allow for a variety of interpretations, which players can then modify to taste if so inclined. For example, Nicolle’s asiatic horse will only show up in some play thoughs of Nevsky, and can readily be removed entirely from the game.

If you have any particular recommendations of histories in English on the topic of the design that I have not listed in the interview, please post here in a reply. I will take advantage of that and try to track them down and read them. The game remains in development, so it is not too late to have an impact.

Thanks again and regards! Volko

LikeLike

Hi! Thank you for the advice! The antidote, I think, is not to refuse to read Delbruck or Oman or Nicolle, but to leaven them with as many other historians as one can access on the topic. At least, that is what I have tried to do, allowing for the likelihood that each historian has something right and other things wrong.

In this respect, a nice feature of games is that they can allow for a variety of interpretations, which players can then modify to taste if so inclined. For example, Nicolle’s asiatic horse will only show up in some play thoughs of Nevsky, and can readily be removed entirely from the game.

If you have any particular recommendations of histories in English on the topic of the design that I have not listed in the interview, please post here in a reply. I will take advantage of that and try to track them down and read them. The game remains in development, so it is not too late to have an impact.

Thanks again and regards! Volko

PS: Ah, nevermind, I see that you already provided that on BGG. I will check those out and search for inconsistencies with the design, thank you very much!

LikeLike

Scandinavians are overall, and I say this as being one, ignorant of Russian history, or even eastern European. Consequently it comes as no surprise that Scandinavians are just as bad as most westerners to interpret the mindset and thinking of contemporary Russians, even though our history is quite entangled.

I’m looking forward to this game both for its historical setting and game mechanisms. It’ll probably encourage me to dig a bit deeper into this historical period as well. I’ve visited many locations of historical interest, but when it comes to actual reading my focus has mostly been from the 19th century and onward.

@Endre Fodstad: what historians and works would you recommend? I’m not dependent on only English, so if you know any works in Russian that would be of interest as well.

LikeLike

My complaint was, as noted above, mainly the reliance on Oman, Delbruck and Nicolle. The cure for that is probably to start with the Verbruggen, France and Keen texts mentioned in the interview, and Bachrach as well. Thomas Maddens Concise History of the Crusades is a bit dry, but it provides an excellent base for more recent crusading research. Jonathan Riley-Smith has a good general overview as well in The Crusades: a History (several editions by now). Then read what has been written in later years on the field. The Journal of Medieval Military History (https://boydellandbrewer.com/series/journal-of-medieval-military-history.html?series=658) has been trundling along now for almost twenty years and has a lot of relevant articles. In general, the background for the Teutonic Order and their relations with the Livonian Order is quite essential to understanding the baltic crusades.

On the baltic crusades spesifically, some of the cited works above are quite useful (Fennels “Crisis of Medieval Russia” is a good overview). William Urban is a specialist in the field and has written scores of articles on the subject. Christiansens book is still viable. Dick Harrison has a very useful introduction to the scandinavian participation from 2005 (Gud vill det! Nordiske Korsfarere under Medeltiden). Kurt Villads Jensen goes more in-depth in “Danske Korstog: Mission og omvendelse i østersøområdet” (2004). Janus Møller Jensen also has a useful bibliography on the baltic crusades. Anti Selart has a good book, “Livland und die Rus’ im 13. Jahrhundert” that I believe got translated and is referred to above as well.

But this list will quickly become enormous. If you provide me with an email address I could send you an excerpt of Devries “Cumultative Bibliography of Medieval Military History and Technology” when I get hold of it again.

The primary sources are of course very important, but the sources on this particular campaign are few. The Rhyming Chronicle of Livonia (there is a 1977 english translation by Urban and Smith, and an excerpt of the military matters here: http://deremilitari.org/2016/09/descriptions-of-warfare-in-the-rhyme-chronicle-of-livonia/), the Chronicle of Novgorod (1914 translation here: http://faculty.washington.edu/dwaugh/rus/texts/MF1914.pdf but I am sure you can find it in russian) and the other available materials collected on the deremilitari website, as this one http://www.deremilitari.org/RESOURCES/SOURCES/baltic1.htm from their useful primary sources list: http://deremilitari.org/primary-sources/ . In general, the Deremilitari.org website, which is the source of the JMMH, has a lot of good publicly available material. I could list a lot of it here, but it is probably easier to go for a search on the website to save this becoming an even bigger post.

LikeLike

You can find some below in the response to Herodotus, and I will try to see if I can comb through my library for more. There is going to be a lot of articles rather than histories, I fear.

In regards to Delbruck and Oman, in my response on the BGG source thread, I note that “They are so out of date they should not be read by anyone without the knowledge to sort the chaff (of which there is a lot, they are extremely outdated) from the wheat (of which there is some, although mostly source quotation at this point, and even that needs some correction).” I think this is the only way to treat them. A lot has happened in the field of history in the hundred years since they wrote their histories, and they have been corrected too many times by now in so many more recent works I think I’ll stand by that assertion.

When it comes to Nicolle’s asiatic horse, the Livonian Rhymed chronicle from which NIcolle’s idea of mongol horse at Peipus comes from has the following to say in Urban and Smith’s translation: “But they had brought along too few people, and the Brothers’ army was also too small. They decided to attack the (Russians) regardless. The latter had many archers, and the battle began with their bold assault on the king’s men. The Brothers’ standards were soon flying in the midst of the archers, and the swords were heard cutting helmets apart. Many from both sides fell dead on the grass. Then the Brothers’ army was completely surrounded, for the Russians had so many troops that there were easily sixty men for every one German”. knight. ” (which makes sense since the Livonian Order (ex-Sword Brothers) had taken catastrophic losees in knights-brothers at Saule – 50 out of the 130 they are reported to have had in 1230 – and likely did not bring their fulll strength of brothers to Peipus anyway.

I do not think Nicolle has much more than those “many archers” to argue for the presence of mongols at the battle. At least that is all he refers to, as I remember it. That is pretty thin, especially considering that it would be the very earliest account of mongols fighting alongside novgorodian russian forces (or possibly any russian forces, I am somewhat shaky on that one) that I know of.

LikeLike

Thank you Endre, that is hugely helpful. I had the Novgorod Chronicle translation but did not have Livonian Rhymed, only cites from historians, I’ll go get that and burrow into the rest that you provided.

I will say that I do not think “reliance on Oman, Delbruck and Nicolle” is fair, given what I have pulled from where for the design. You may want to try out the game–would love to have you on the team–to see for yourself what is actually in it. Even with detailed description by a designer, one does not get any game’s interactions without playing it.

There is not really much in NEVSKY from Oman, from Delbruck mainly the reference to 40 days as a tradition and conversion to mercenary service, which I have seen elsewhere too, and the idea to use wedge shaped pieces horse, as he discussed charging in wedge shape (no other effect on play, as this is not a tactical but rather an operational focus).

I would say most in the design came from Selart, Urban, Christiansen, and Nicolle. As for Nicolle, I am well aware of the controversy and feel that I have accounted for that with options for play. Nicolle is useful in providing his take on operational details of this particular campaign that most historians don’t get down to. Where Nicolle contradicts others, I have not relied on him; instead, I have included the various possibilities.

In general, I prefer to read and consider everything that I can get hands on, rather than to rely on anyone to tell me what not to read.

Best, Volko

LikeLike

Thank you. The reason Nicolle can be so detailed on operational details is probably because he makes a lot of stuff up 🙂

Ok, that was probably a bit too harsh. But there is a truth to it. As stated, I was appalled at the quality of his scandinavian books, which is the region I know the most about.

The 40-day period is a odd bird. It is an amalgam of a number of different english and french sources from the 12th to the 14th century where the number 40 pops up a lot, in a lot of different ways. Sometimes., a noble or king will demand a retainer show up with his retinue and 40 days of provisions. Sometimes, there is a document that flat out states 40 days of feudal obligation for a retinue. Other documents say 40 days in peacetime and two months in wartime. Some only tell them to show up if called up, thank you. In all likelihood, there was a great variety of different agreements. Delbruck and Oman decided this was well applicable to half a millenium of history, and some have followed them later.

During the period covered by this game in the better-studied countries (such as England), the feudal obligation was well on the way to be replaced by a tax on nobles and commoners both (Simpkins discusses this on his article on Longshank’s scottish wars here: https://bit.ly/2L5RSgY). And in other regions of Europe, entirely different systems abounded. The norwegian king Haakon IV was able to have the entire leidang out for most of the summer and into october (when the freemen went home: they had harvests to oversee and the campaign was going nowhere).

The general consensus seems to be that the 40-day military obligation is simply too much of an oversimplification. It doesn’t work as described even in its “heyday”.

I can probably get some plays in considering I am. going on paternity leave soon, and I know that ulrik (the BGG fellow who comments on COIN a lot and introduced me to it) would happily oblige spending some summer vacation testing wargames. I am guessing you can send me some files to print or something along those lines? I’ll PM you on BGG and add some details.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Endre, fantastic.

I had a similar impression of the 40-days, which has always struck me as an impractical number. In the game, I call the turns “40 days” in recognition of the tradition (it actually works out closer to 45 days, so there is some wasted time too). But lords and vassals are serving for a range of turns, only a few of them for only 40 days, and that service ends up lengthening or going short from a wide variety of causes including, naturally, payments.

Simpkin–excellent–looks like the chapter is about Edward II not Longshanks, but still, a great start to my research for Volume II!

Thanks that is wonderful about your being able to take a look at the design. I have emailed you and developer Wendell. He will set you up with our Dropbox folders.

Cheers! Volko

LikeLike

Payments and victuals grease the wheels of war 🙂

Ah, sorry about that. I haven’t read the article recentlty. Prestwich has more on that subject.

LikeLiked by 1 person