My introduction to the boardgaming hobby (as opposed to say, just boardgames in general) came via my father’s very tiny collection of Avalon Hill titles all the way back in 1983-84. These were Civilization, Source of the Nile, Statis Pro Baseball and Freedom in the Galaxy.

Of the four, Freedom in the Galaxy is my favorite. This game was published by SPI in 1979 and later reprinted in a new edition by Avalon Hill in 1981. This game is very much a product of the late 70’s early 80’s gaming, a time when hex and counter strategy games had reached an apex and had branched out into science fiction and fantasy (led by Ares Magazine, a spin-off SPI game magazine created to deal specifically with those genres).

It’s a two player space opera wargame between an evil oppressive Galactic Empire and an upstart rebellion that initially consists of just a small group of characters intent on overthrowing the tyrannical emperor. If that sounds familiar it should. This game was essentially supposed to be: “Star Wars: The Wargame”. Much like it’s cousin by SPI, War of the Ring, the publisher that obtained a license for a game about Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings books probably tried to do the same for George Lucas’s creation. It’s a favorite among dedicated fans whom have played it for the last 30 years so they could have the closest experience to a Star Wars like wargame. Considering that Fantasy Flight Games recently published Star Wars: Rebellion, we now have THE official Star Wars licensed strategy game which makes Freedom in the Galaxy obsolete right?

For some perhaps. For me this game came into its own with its rich backstory and cornucopia of detail that is quite an achievement considering that the game is smaller than a lot of similar wargames of its time. They are also two different kinds of beasts. Star Wars: Rebellion is a game with deep strategy embedded in its card play mixed in with a simple but robust military engine coupled with a character system that either leads the military forces on the map or goes on missions to fulfill objectives or projects important to their side’s cause. There’s a lot of action in a game that plays out the narrative from the original movie trilogy (Episodes 4 through 6) and takes about 4 hours to finish. It’s a product for a modern audience that generally wants to play a game in a single afternoon or evening.

Freedom in the Galaxy leans much more on the conflict simulation scale of gaming. Rather than creating a game that was playable in one sitting, what John Butterfield (UPDATE: and Howard Barasch, see comments) created was something more akin to a classic operational wargame that rewards long term strategy while remaining flexible enough to respond to an evolving board situation. 20 hour (or more) games were fairly typical products of that era as you peruse through the titles available from that time. It’s a different kind of gaming experience to go through various 2-3 hour sessions executing your blueprint for victory while fending off random events and your opponent whilst trying to throw in wrenches to wreck the opposition’s schemes. Instead of gaining satisfaction after a single play, the payoff doesn’t occur until the end when you’ve had a chance to watch your strategy unfold over time (or collapse in a heap).

Thus, despite the similar subject matter, there’s room for both titles in my collection, depending on what you’re in the mood for at any given time. Note that Freedom in the Galaxy does have shorter scenarios (that deal with smaller portions of the map) which range from 1 to 5 hours but the real meat of the game is playing the campaign scenario which starts with a Galaxy under iron rule and only a small band of rebel characters with a simple dream of revolution but a gleam in their eyes.

These are not the minis you are looking for…

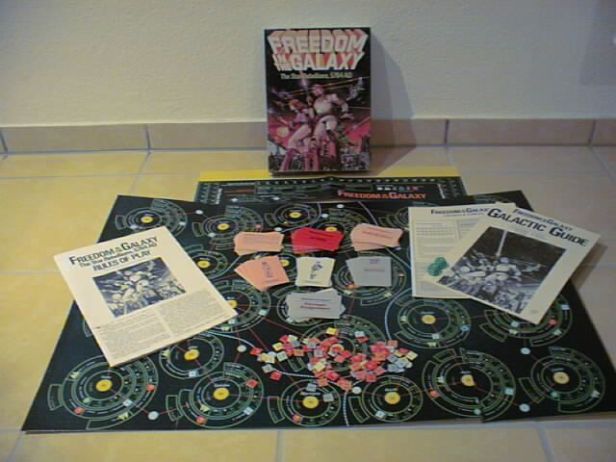

True to its heritage this game comes with a pair of counter sheets of 1/2 inch chits for a total of about 400, unlike Fantasy Flight Game’s production filled with miniatures. These counters are pretty standard in that they are used to represent not just the physical location of characters and military units in the game but also are markers for information purposes (like the state of planetary defenses or political alignments of these planets to just name a couple.) It also comes with about 130 or so cards representing characters, items, missions, outcomes for those missions (called Action events), general random events and cards for restrictions on the movement of imperial units (called Strategic Assignment).

There are some physical differences between the two editions though: the SPI cardstock was thinner and smaller than the Avalon Hill edition. SPI had a paper map while Avalon Hill’s was a mounted map with an additional cardstock for other game tracks and information. Both come with one rule book, one set of charts and a separate book called the Galactic Guide which had most of the game’s back story and descriptions (as well as a bestiary for when your characters encountered the local fauna). The components are all quite functional though a bit dated in style and color. But I grew up with it and other similar games so I find it charming like a favorite old vinyl record album.

This day will long be remembered…

As mentioned before Freedom in the Galaxy is a two player game. One will be the Rebel player while the other becomes the Imperial player. Though I have heard of multi-player games where the rebels split into teams so each member is handling a specific group of characters. For the campaign game the Rebels must acquire 26 victory points by turn 20 or lose the game. The Imperials can win automatically by killing all the rebel characters or destroying the rebel secret base with no rebel controlled planets on the map (it wouldn’t be a Star Wars like game without a secret base or planet busting doomsday weapon!). The rebels get VPs by controlling planets. In the beginning of the game the Empire controls all the planets. The Rebels must work to convince these worlds to revolt and throw off their shackles. Worlds vary in value but award at least 1 VP and can be as valuable as 5 VP.

The conflict plays out on the map of the galaxy. This design goes for an informational “schematic” look to represent the galaxy rather than use an astronomy aesthetic. There are 25 star systems, many with more than one planet for a total of 51 worlds. These systems are grouped into five provinces organized into four outlying provinces surrounding a center one. Each province has a capital and the center province (1) also has the throne planet, the seat of the Empire. Each planet in the game is inhabited by one or more races. Many are native to just the one, but there are 8 in the game that populate more than one planet (the so called “star faring races”) and each of them (with one exception) also have a “home” planet where the alien race originated from. This aspect drives the game’s politics. All planets have an alignment in favor or against the Empire. You keep track of this on the map using a loyalty marker. There are five values which you can think of as +2 to -2 (depending on who it favors) and they bear labels indicating how the planet feels about the Empire: Patriotic, Loyal, Neutral, Dissent, Unrest. Each planet can has its alignment shift due to missions or random events. Significant shifts (two or more spaces at once, open revolt, the Rebels gaining control of a planet) can cause a domino effect and shift more than just one planet at a time. This effect is more pronounced when it impacts a star faring race rather than just a local race, a race’s home world vs just one they happen to occupy or an imperial capital vs just an imperial world. One well timed revolt can cascade and trigger multiple uprisings if the Rebels work hard to put lots of planets into Unrest first. The Empire can benefit from a domino effect but it’s usually more muted.

Each planet also has a planetary defense base (PDB) which is basically a detection and defense infrastructure. The PDB status can be active (Up) or inactive (Down) and has three levels of effectiveness numbered from 0 to 2. Aside from that the planets have physical locations where characters and military units can move around. All have an “Orbit Box” which is exactly what it sounds like: a place where military units and spacecraft are orbiting the planet. There are also spaces called “Environs”, planets have at least one such space and can have as many as three. These represent major regions of the planet surface and they can be one of six types: heavily urbanized areas, wild natural untamed territories and various exotic locales that represent extreme environments, like very hot environments, underground cave systems, very wet or underwater and even high in the upper atmosphere. These locations will be populated by a specific race, they have size that limits how many military units may deploy there as well a resource value. Many will have the name of a native creature that prowls the area or any other special characteristics that can impact game play.

Remember, a Player can feel the Sequence of Play flowing through him

The games plays as a series of game turns up to a maximum of twenty in the Galactic Game. It can end sooner if either side achieves its automatic victory conditions. One game turn consists of five different parts. There is an administrative portion where random game events occur, the Empire gets to collect resources via taxation of planets (if able) and both sides get to spend resources to build up armies and planetary defenses. The rebels get resources primarily through revolts of planets. The next four parts are just player turns alternating between Rebels and Imperials, both will get two each for a total of four.

A player turn typically consists of a movement phase (a.k.a “Operations Phase“), then a search phase and finally a missions phase. The movement portion is subdivided into segments or steps and can be a bit intricate because military units will get to move twice: once to move between any two worlds and fight space battles, and then movement within a world (whether to land from orbit or shift between environs) and fight ground battles. And finally after everything is done moving you need to organize the stacks into troops (With leaders if they have them) and characters ready to go on missions.

It’s noteworthy that unlike other space opera games, military units are both troops and spaceships but they can only function as one or the other depending on where they’re located. Each unit has a surface strength and a space strength (expressed as two numbers separated by dash, like 1-2, 3-2, 4-3 etc). Combat is odds based (3-1, 2-1, 1-2, etc.) with leaders providing favorable shifts and the terrain (if fighting on the surface of a planet) providing similar advantages or penalties. The PDB can also be attacked from space or it can also help defend your units in a space battle by providing odds shifts. Units take losses equal to their strength but there’s no step loss degrading a unit. It’s all or nothing. If you generate two hits against a 3 strength unit it won’t suffer a scratch, if you can assign three it’s destroyed and removed to the force pool. This makes high strength units much more durable than low strength ones (units in the game will vary from 1 to 5 strength points). One interesting wrinkle is that Imperial units (except 1-0 militia) deploy and move face down hiding their value. This allows the Empire to bluff and obfuscate their strength with the Rebels not quite sure what they’re up against until they actually encounter them (whether through combat or other actions).

Characters also move in this phase, either as military leaders with a stack of troops or independently in their spaceships with other characters with the object of slipping undetected into enemy territory to perform missions. Once again the PDB is the primary way to detect opposing enemy agents (with the help of orbiting fleets if any) and even damage their spaceship on their way to the surface. Some results allow for blasting a ship completely out of the sky killing everyone on board, the wise player will do their utmost to avoid the potential for such a result.

The opposing player will get to react to these moves either by intercepting enemy military units in space or on the surface of a planet and forcing battles or if enemy characters have been detected (usually by the PDB) military troops can move and will have the opportunity to try and find these characters and provoke a firefight later in the search phase, which comes after all movement and battle is complete.

The search phase is when the opponent can use friendly troops (or characters) to find enemy characters that are trying to infiltrate your planets. A successful search results in a squad of troops engaging the characters in combat and they might kill or capture them. While this is the official portion when a search occurs, this mechanism can occur again when Characters are going on missions and events allow an opposing player to conduct more searches.

The missions phase is in many ways the heart of the game because while military troops are required to control planets and defeat enemy armies and fleets the characters are the ones than can trigger political shifts, revolts and other dramatic actions in the game via missions. Characters in an environ that aren’t leading military troops can be assigned missions. Diplomacy missions can change the political alignment of the planets. Coups (on places that are susceptible to them) can cause wild shifts of support for or against the rebel cause. Gather information (spying) can obtain secrets, detect enemy characters and reveal Imperial troops. Start/Stop Rebellion triggers the spark (or douses the flame) of open Rebellion once the political alignment has been shifted completely against the Empire (the Unrest space on the planet’s political track), it’s also one of the ways the Rebel player puts troops on the map to challenge the Imperial army and the primary way of adding resources to the secret base. Free Prisoners is basically a jail-break to free characters that have been captured by enemy squads or characters. Sabotage missions can take down PDBs or eliminate an enemy military unit. Start Rebel Camp allows the player to establish a cell or network that that can perform basic missions without risk to your characters which forces the empire to mass troops in order to remove this thorn. Both sides can obtain more characters via missions (Gain Allies), though the Empire starts with 10 characters and can only acquire two more while the Rebels start with 14 and eventually can recruit 6 more. Not to mentions rebels can go on missions to acquire “possessions”, a vast array of interesting items from spaceships and weapons to objects and companions (like pets or androids a la C3P0 of Stars Wars fame). There are twenty of them in the game (including the spaceships) and are represented by cards with pictures and information about their game benefits and limitations. Spaceships also have a counter to pinpoint their physical location like characters and whether they are damaged or not by flipping the counter to the appropriate side.

You form your mission groups with the characters assigned however you want. Each possible mission in the game has an associated letter and you use the “Action Event” deck to draw cards up to the environ’s size and read what happens to your missions while checking for the letters to see if you accomplished them. As long as your characters survive the events they complete the mission but they need to draw the right letters in order to have a positive outcome. A few missions can be dangerous (like Assassination) and have negative consequences if you aren’t successful. Your team might get captured or killed! It should be pointed out that failure is more common than success and sometimes you’ll have to spend a chunk of time in one place to accomplish what you want to do.

Characters have different stats that help with different parts of the game: combat (for encounters with enemy squads or characters, local brawls and most creatures), endurance (basically how many wounds they can take before dying), intelligence (primarily for missions), leadership for military battles or subversive activities, navigation for piloting spaceships and diplomacy for, well, diplomatic missions. Some characters bear titles (Prince, Princess, Knight, Governor) which can give them a leg up on some missions on those planets that recognize them. Even a character on his home planet will an edge. Many have extra advantages applicable to missions in the form of bonus draws (more cards but without nasty events to worry about!), others have talents that give them benefits in other parts of the game or allow them to ignore some types of events. Possessions can work in a similar fashion and a big part of the fun is putting together different characters and items that complement each other and provide synergy for specific missions or a group that is quite flexible and can accomplish multiple mission types.

Character combat, unlike the military one, is a differential combat results table and characters will frequently find themselves in a fight, whether because they encounter unruly natives or creatures during a mission or fight off enemy troop squads that are searching for them or stumble into. Depending on the opponent the combat may be intended to capture characters which gives combat shift benefits to the defender (as the attacker tries to shoot to disable rather than kill), though irate locals and creatures always engage in mortal combat. The defender has to choose which characters are active or inactive and can attempt to break off from the combat round before the fighting starts, though failure to break off results in a negative shift for that round. Still, disengaging and fleeing is often the best course of action even if the odds are favorable since you don’t want to risk your characters suffering hits as it degrades their future performance and lowers their chances of survival. Each hit causes a wound on a character and they can take as many wounds as their endurance rating. These are kept track on a separate sheet of paper with list of character and a number of boxes equal to their endurance rating. Characters must rest during a missions phase (i.e. do nothing) to heal their wounds though there’s a medical kit item that heals all characters and one Rebel character is a doctor as well.

The end of the mission phase is also the end of a player turn, and during the Empire’s player turn you check to see whether any planet’s control status has changed. You would think it’s simple but a chart lays out a combination of whether one side or both’s military units are present on the planet plus the status of the PDB. Status and control are actually two separate concepts in the game. For example, a planet may be nominally in an Imperial controlled state but if the planet is occupied by Rebels and the planetary defense are down the Empire doesn’t actually “control” it (which is important for say… collecting taxes!). Once the Empire’s second player turn is over the entire galactic game turn is finished and you move to the next one starting with the galactic events and admin phase. Repeat until victory or turn 20.

That’s an anatomy of a game turn but it leaves out so much. To explain in proper detail every single game system and how they interact would probably require many individual blog posts. I’ll focus instead on how the general game experience is for each side and how the asymmetric nature of their capabilities drives very different kinds of strategies and concerns during a game.

The more you tighten your grip, the more systems will slip through your fingers…

The Imperial player begins with a winning board position but has to hustle out of the gate. The game setup starts the empire with a very sparse military position and scattered characters. For the most part the setup allows you build up an initial force of units and PDBs and you can balance your expenditures as you see fit. Just remember this start is only temporary and in no way resembles the final configuration of forces you will want on the map. The starting position should lay the foundation for how you want to deploy your forces on the map.

As the empire you have to work around one very big constraint at the beginning of the game: The Strategic Assignment. This is a deck of cards that lists two provinces (from 1 to 5) and you draw one card each turn. That card tells you in which two provinces military units and characters can move freely within those two to any planets, in the three other provinces all units are restricted to the planet they are in with a few exceptions (Capitals, home worlds and planets in rebellion). Prior to game play you set up this deck any way you wish and the challenge will be to organize a schedule such that no province is out of Assignment for too long so you can move and deploy your forces to them and change up the character teams.

You have a force pool of 110 units you have to work with ranging from local militia (1-0) up to front line troops, elite units, suicide squads (units which automatically eliminate found rebel characters and themselves in the process!) and atrocity units. Yes, atrocity units! Like.. The Planetary Stabilizer… basically this universe’s version of the Death Star. That’s how you want to blow up the rebel secret base to try to win the game outright! Though note that if the Rebellion is in full swing you will no longer be able to trigger victory just by destroying the base. Another option is to aggressively hunt down the rebels and try to capture them all or wipe them out. But this is easier said than done thanks to the Strategic Assignment. The Rebels will often scamper away to less protected places and locations where it’s easier to hide. In the end, you can always outlast the rebels and prevent them from gaining control of the necessary number of points to win the game on Turn 20.

Another basic concern is handling the flow of resources provided primarily by taxation. Each galactic game turn one province is scheduled to be taxed and you have to decide whether to tax a planet at full resource value, which will incur a negative political shift, tax at half which changes nothing or no taxation at all which will improve the Empire’s stance with the population (up to a point, no planet can improve beyond the starting political alignment printed on the map). In many cases you can be content with half the resources since it can be very hard to shift political alignments but if a planet is slipping into Unrest it may be worthwhile to not tax the planet or if shifting will set them at Patriotic that is certainly worth doing especially if the current assignment won’t let you deal with it through conventional means. Conversely some of the richest worlds are often a good target for full taxation, especially if they are easily accessible despite the Strategic Assignment and you can entrust the Imperial diplomatic corps (in the form of the Imperial character Senator Dermond) to smooth ruffled feathers.

Another big thing the Empire has to deal with are planet secrets. There are sixteen markers and they are assigned randomly at game start (and which can be a big part of replayability; for some secrets, certain locations can be more or less beneficial to either side). The empire will be able to inspect them and see each world’s secret attribute from the beginning and plan accordingly. For the most part these are important locations with special characteristics the Empire doesn’t really want the rebels to learn about easily and in many cases will want to have a strong garrison. One is an industrial world which provides extra resources for the empire off the books every turn regardless of the province of taxation. A similar one is gem world which is a mining planet. There’s also the Slave world where the labor provides additional resources. If the rebels cause a revolt on these worlds the Empire loses the extra resources permanently for the rest of the game! Another is the cloning planet where a successful “Gain Allies” mission allows you to recover a previously dead character, and control of the planet is irrelevant to this attribute. This planet is the reason why capturing can be more worthwhile than merely killing a character; capture is the only way to guarantee the enemy can’t do anything against you. There’s a casino planet which can make gathering useful possessions much easier for the rebels, a spacecraft industry planet which similarly makes it easier to acquire spaceships. Some worlds are simply peculiar and provide other challenges to characters: a mutant world with very nasty creatures and locals, a drug world which enhances character abilities but inflicts wounds on them which forces you to leave before it’s too late and a hyper world which allows characters to do two missions at once! Some worlds have extreme political alignments: one which secretly hates the empire and makes it really easy to shift into revolt and very hard for Empire to convince otherwise, and an Empire forever planet that automatically shifts to Patriotic upon reveal, can be taxed fully with no bad repercussions and is extremely hard for the rebels to bend to their cause. There’s a dead planet where the Planetary Stabilizer was apparently tested on and the reveal can cause political uproar and negative shifts against the Empire. Lastly, the empire has a few bureaucracies. The IPOC (Imperial Peace Operations Center) that keeps track of all imperial military units and conversion into a rebel controlled world will force the Empire to deploy all units face up. There’s a security planet called “Trap!” which can automatically capture rebels if they land on it revealing the marker (which is why one does not simply land on planet secrets!) It also serves as a prison that requires no units as guards. Finally there’s an archive planet which can reveal ALL planet secrets at once through a single Intelligence mission!

Evacuate in our moment of triumph? I think you overestimate their chances…

For the Empire the game is mostly about building up Imperial forces, assemble a few good teams to shift as many planets as possible into Patriotic in the beginning and positioning their troops with military leaders to help track down rebels and dealing with the occasional rebellion. A big part of planning is where to put the entire force pool on the map, what planets to guard heavily and which ones will have a token force that will pull back once the revolts have begun. You don’t have enough of a force pool to defend strongly everywhere. As the Empire you will have to choose which worlds to let go and which ones to draw a line on the sand. Handling the build up is equally important because the strong elite units and level 2 PDBs cost maintenance. The Empire plays the part of the cat chasing the rebel mice all over the galaxy. For the most part you are just trying to delay the inevitable but if you can capture or kill some rebels along the way so much the better. Once your entire force pool is on the map then it becomes a matter of damage control when the Rebels trigger open revolt (especially if they can cause a domino effect that will cause rebellions in many worlds at once). One fundamental disadvantage for the Empire is that a combat with an equal force of Rebels and Imperial troops the rebels wil generally have the upper hand unless the troops are elite. If you have managed to find out where the Rebel Secret base is then you can move your Planetary Stabilizer to destroy it, only it’s not worthwhile if the Rebels have spent almost all of the resources they accumulated.

You will be doing less missions than the Rebels and your power is in your military units and properly assessing which worlds need a strong garrison, how many strong reserve units should be held at capital worlds to respond to a rebellion and where to keep your strongest fleets with your most able space admirals to crush rebel threats. In this sense the Empire plays along the lines of a more traditional wargame with armies and leaders and picking the places to defend or fall back on, while the characters and missions are executed in support of these goals. Good Imperial play will see the Empire bend and stretch but ultimately not break against the best rebel players.

Never tell me the odds…

The rebellion has much different concerns than its imperial counterpart. You start with 0 military units! But that’s not an issue, your strength is in the vast number of characters and possessions at your disposal. You want to get these in play as quickly as possible and assemble large flexible teams capable of slipping past strong imperial defenses and start working on pushing imperial worlds closer to revolt. Primarily accomplished via Diplomacy but there are still other ways to influence the population and many other useful missions you can do in the meanwhile. Setting up rebel camps, gathering intelligence, gain allies, scavenge for possessions, maybe even steal imperial resources if you’re on a planet that was taxed or you’re in a Capital planet.

While the Empire spends time building up its military force pool you’re building up your pool of characters and possessions. You’re in a race against time and there’s a lot of hidden information you have to plan around; the strategic assignment that tells you which worlds the Empire can move to and react to in the current game turn meaning some provinces and systems are safer than others. Imperial troops move in secret and you don’t know their strength until they reveal themselves for a particular game function. Planet secrets are another hidden source of information with many of them being useful to the rebel cause.

One big thing is that the Rebels should play the long game but at the same time watch out for opportunities to hit the Imperials where it hurts; for example while it’s not advisable to to turn planets over one by one and instead focus on trying to get several of your ducks lined up before triggering the first revolt, many planets are ALWAYS worth an immediate rebellion (like the Imperial secret industry, gem and slave worlds that are a source of important revenue to the Empire). The Rebels must plan ahead but also allow room for some chaos so the Empire doesn’t ignore you and simply set themselves up with no roadblocks.

I find your lack of patience disturbing…

The Rebels will be conducting the most missions in the game so they are heavily affected by the action event deck and the vagaries of mission success. Truth be told, success is hard to come by even when you stack the mission in your favor and maximize the bonus draws. For players who want instant gratification, the mission system will be a severe source of frustration. You have to play the odds and plan for failure to occur often. For many places sheer persistence will be required to accomplish your goals.

Once the Rebels have all the mission groups they want on the map and have turned enough systems to make the galaxy one big powder keg just waiting for a spark, the game for the Rebels shifts into stocking up on those resource points the revolts bring in. The point is to accumulate enough to purchase the elite rebel forces that can only be brought into play via the rebel secret base. Backed by their big fleets and armies the Rebels can start looking to target the tough Imperial Capitals and other big VP worlds to win the game. Of course, once the base is revealed the Empire abandons all pretenses that the Galaxy is all cupcakes and Imperial parades and the strategic assignment restrictions are completely lifted. At that point the game shifts almost completely into wargame mode.

At start, the rebel player’s experience hews more closely to that of a lightweight tabletop RPG focused on the characters, their abilities, picking up useful objects, companions, larger and better spaceships, recruiting allies and running missions. The military aspect of the rebellion doesn’t come into play until much later. It becomes a big shift because the player needs to time it right. Note that for the rebels the point isn’t to utterly defeat the Empire militarily (I don’t think that’s really possible! Just look at the combined space strength of both force pools), just achieve enough local victories to turn planets into Rebel Control, accumulate enough of them and win the game. Even if the Rebels were forced to just settle for 1 VP planets they would need only half the map to claim victory, but the important home worlds and capital planets will bring the actual number of planets required for victory down to much less, maybe as little as just one third of the galaxy. Good rebel play will persevere in the face of frequent failure, exploit opportunities as they become available and sow just enough chaos to keep the Empire off balance until you’re ready to light the match and spark revolution across the stars. Enough of these planets rising up at the same will overwhelm the Empire’s ability to react effectively and may be just enough to break through and take areas the Imperials didn’t plan on giving up.

Do, or do not, there is no Try…

In terms of game balance, the original rules were biased in favor of the Empire. The Nick Palmer variant introduced some crucial rules changes to make the game more competitive, primarily involving tighter restrictions on the Strategic Assignment exceptions and making the PDB irrelevant to planets attaining Rebel Control status (these were released in the magazine The General Vol 20 no. 4).

There is so much more to say about this game, but suffice to say that nearly every aspect and rule is meant to provide options to players in accomplishing their goals. Sure, a lot of stuff is situational (it’s rare to see the Empire land on the rebel secret base to steal its resources; the Imperial treasury would have to be in a really ugly state to be that desperate). The level of detail the game brings means that you can’t chow through the game in just a few hours (unless playing a smaller one province scenario which plays a reduced version of the game in just a portion of the map).

In closing, to truly play and appreciate the scope of the game and all it has to offer you have to absorb it in multiple bite-sized sessions until you can eat the whole elephant. Repeated playings are required to understand how certain strategies or missions impact the game is it unfolds. That’s not to say it’s a game without flaws. Many game mechanics are showing their age and others will simply drive you up a wall, but there’s no better feeling than laying out a long term plan and seeing it through to fruition. This aspect is what makes Freedom in the Galaxy a familiar cousin to today’s complex wargames (whether in cardboard form or computer based) and worth exploring. After all, it IS a John Butterfield game! (UPDATE: and Howard Barasch, sorry Howard!)

Wow, I didn’t even know this one existed! But it seems like the designer of Star Wars: Rebellion did and made sure to incorporate some of the best concepts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glorying in those awesome Avalon Hill covers!!!

I never played this game, but I remember the talk about it in the General magazine when it came out. Wish I had tried it at the time.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I very much enjoyed this detailed profile of a game designed long, long age …

One correction: Howard Barasch was the original game designer and created the backstory, I took over when he left SPI mid-design. We are co-designers of the game.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ah, thanks for the correction and the good words John. I continue to enjoy your game designs as time allows me to get them on the table.

LikeLike

I remember spending considerable time playing this game when I was a teen — enjoyed it signifcantly, though I don’t think I ever finished. I brought it out again to kick around a few years ago, as my son first got interested in Star Wars. Of course, given the limits of time, actually playing the game enough to get/recall a sense of its subtleties seems out of the question, much as is playing through the Grand Campaign of a similarly monstrous game: Victory Games’ old Vietnam 1965-1975.

So the interesting thing is that there are basically two paths toward ‘modernizing’ FITG: the Fantasy Flight Games’ Star Wars Rebellion, which is a great game, comparatively fast, lush, and replayable. The second, which hasn’t occurred yet, is some version of Volko Ruhnke’s COIN (counterinsurgency) system (a la Fire in the Lake or Pendragon).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pretty much. More people will gravitate towards Rebellion because it’s official. I like the idea of COIN based on the FitG universe. Maybe one day it can be done. Lots of things even translate directly (for example: Loyalty vs Support/Opposition).

LikeLike