In late 2016, I discovered Compass Games and have been following several of their games over the past few months, culminating in my purchase of Saipan – The Bloody Rock, which shipped last week. I also have done an interview with John Poniske previously covering one of his new upcoming games The Berlin Airlift from Legion Wargames. So, after that interview went well, and due to the fact that I had an interest in one of his Compass Games designs, Revolution Road, which is being designed with the help of Bill Morgal, I asked and they both agreed to indulge me. Thanks John for doing this all over again in such short order. I am a fan of the Revolutionary War and have played several games on the subject, including Liberty or Death: The American Insurrection from GMT Games and Saratoga from Turning Point Simulations, and definitely am always on the lookout for quality games that cover this seminal event. Here is the interview:

Grant: I’m really excited about your upcoming game Revolution Road from Compass Games. Why did you want to tackle a Revolutionary War game?

John: Simply put – John Adams! Decades ago, I became enamored of the Revolutionary  War musical “1776,” in which John Adams was portrayed as an obnoxious but tireless and determined patriot. My interest in our second president was revived with the award winning tv mini-series John Adams. I sought out and read the Pulitzer-prize winning John Adams by David McCullough, which prompted a summer vacation to Braintree and Boston, Massachusetts. While there, my wife and I visited all the Revolutionary War sites and I kept thinking that the conflicts that ignited the Revolution had not been fully covered by our gaming community. There were a couple designs on Bunker Hill, yes, but nothing I could find on the March to Concord. I began design work on the twin games when I got back home and as luck would have it, I learned my good friend Bill Morgal had independently decided the same thing – so we collaborated.

War musical “1776,” in which John Adams was portrayed as an obnoxious but tireless and determined patriot. My interest in our second president was revived with the award winning tv mini-series John Adams. I sought out and read the Pulitzer-prize winning John Adams by David McCullough, which prompted a summer vacation to Braintree and Boston, Massachusetts. While there, my wife and I visited all the Revolutionary War sites and I kept thinking that the conflicts that ignited the Revolution had not been fully covered by our gaming community. There were a couple designs on Bunker Hill, yes, but nothing I could find on the March to Concord. I began design work on the twin games when I got back home and as luck would have it, I learned my good friend Bill Morgal had independently decided the same thing – so we collaborated.

Grant: What other Revolutionary War games did you use for inspiration?

John: Me, none. The only other Revolutionary War game I have played was the American Heritage Series Skirmish, and that was back in grade school. On the other hand, I have followed Mark Miklos’ Battles of the American Revolution series by GMT Games, although I’m pretty sure my ideas for Revolution Road were not influenced by these. Bill may answer this differently.

Bill: I am a big fan of Hold the Line from Worthington Games and I have played some of the GMT Battles of the American Revolution titles. I can’t say that any were any real influence though.

Bill: I am a big fan of Hold the Line from Worthington Games and I have played some of the GMT Battles of the American Revolution titles. I can’t say that any were any real influence though.

John: Oops, totally forgot about Worthington’s Hold the Line. It’s been a couple…, it’s been a while since I played it.

Grant: Who is your co-designer Bill Morgal and how did you decide to design together?

John: Bill is a good friend I met at WBC years ago…but I’ll let Bill tell his own story.

Bill: Board games have always been a part of my life. A few years back, I answered a call to playtest Colonialism by Scott Liebbrandt. It is a hidden gem. I had ideas to improve the prototype and was particularly proud of the cards I made. Unfortunately, the publishers weren’t. I collaborated with Scott on other games and found that I really enjoyed creating game art. I also began creating my own games. One of my pet projects is Roanoke, about early colonial settlements in Maryland and Virginia. Another design I have ready to publish is Newton’s Noggin, although not a wargame, its card mechanics make it rich in strategy. Revolution Road will be the first work I have done to see the light of day.

As for John, I met him at WBC when he asked to join in on a game with my son and I at the Queen demo table. It was the start of a great friendship. I owe him a lot. He promotes my artwork and thanks to him Compass agreed to use my art in Revolution Road. During that first meeting, I learned about his Lincoln’s War and found he needed play testers. He allowed me to help with it a bit and since then I have assisted with some of his other designs including Ball’s Bluff and Black Eagles. Along the way I graduated from Paint to GIMP to Photoshop. I am currently working on the artwork and play-testing for three of John’s latest designs: Belmont, Blood on the Ohio and Wolf Tone’s Rising.

It’s interesting how we came to collaborate on Revolution Road. I had done some reading and early design work on a game about Lexington and Concord and was particularly psyched because, as far as I knew, no one had approached this theme. I took a cue from my mentor, John, who excels at finding unique game topics. While play-testing one of John’s games, he mentioned that he’d returned from a New England vacation and was considering, you got it…Lexington and Concord. My heart sank. He must have heard something in my voice because he asked what was wrong. I told him I’d already started something like that. Great guy that he is, he immediately suggested we throw in together. Several years have passed and the result of that collaboration is Revolution Road.

Grant: What battles does Revolution Road cover? Why include both of these games in the same box?

John: Lexington, Concord, the British retreat from Boston to Concord and of course the misnamed battle – Bunker Hill. As asymmetric as the British march to and from Concord was, it has not been gamed before, whereas, several designs on Bunker Hill do exist (William Marsh’s 1995 board version, and Lloyd Krassner’s 2004 card version, to name two). However, we felt that having done the former, we had to do the latter as it was the culmination of the former actions. Both designs share a number of concepts but are really two entirely different games. The march on Concord is see-saw action that is dependent on maneuver. Bunker Hill is a bloody slugfest.

Grant: What are the challenges with designing a game set in the 16th century? How did you overcome these challenges in the design?

Bill: Fighting myth was one challenge John and I faced with Revolution Road. There is so much myth associated with the American Revolution it is very easy to fall in the trap of accidentally introducing generally accepted inaccuracies into the game. The historical events that occurred in From Boston to Concord and Bunker Hill are prime examples. Thanks to Longfellow, and popular knowledge more infused with patriotism than fact, few people know how events really played out during the night of Paul Revere’s ride. What really happened before the sun dawned along the Boston countryside on April 19th, 1775 is much more fascinating than the glossed over facts many of us were taught in school. The mechanics used for nightriders in From Boston to Concord do not fall into this trap. Paul Revere is not a lone figure galloping through the night. Instead, we incorporated the three most well-known nightriders, Paul Revere, William Dawes and  Samuel Prescott. Nightriders can both be captured, and if captured, can attempt escape. It is John’s and my hope that learning and playing the game will spark an interest in players to find out more of the history the two games are concerned with, especially with those that might think ‘that’s not how I remember it.’ How did we overcome all this? Lots and lots of reading. Paul Revere’s Ride by David Hackett Fischer, American Spring by Walter R. Borneman and Bunker Hill, a City, a Siege, a Revolution by Nathaniel Philbrick are my favorites and were of immense help. John may want to add some of his favorites.

Samuel Prescott. Nightriders can both be captured, and if captured, can attempt escape. It is John’s and my hope that learning and playing the game will spark an interest in players to find out more of the history the two games are concerned with, especially with those that might think ‘that’s not how I remember it.’ How did we overcome all this? Lots and lots of reading. Paul Revere’s Ride by David Hackett Fischer, American Spring by Walter R. Borneman and Bunker Hill, a City, a Siege, a Revolution by Nathaniel Philbrick are my favorites and were of immense help. John may want to add some of his favorites.

John: Bill mentioned my favorites: Bunker Hill, a City, a Siege, a Revolution by Nathaniel Philbrick and American Spring by Walter R. Borneman.

Grant: Let’s first talk about From Boston to Concord. What is the historical significance of this event and the famous saying “The Shot Heard ‘Round the World”?

John: The history preceding these events goes well beyond the truncated version we learn in school. Animosity existed on both sides stretching back to the French and Indian War and beyond even to King Philip’s War. There are two decidedly different points of view on the topic of the American Revolution and to understand one you have to take into account the other. The British no more think they acted wrongly then we think we did. The March out of Boston to Concord was to be a simple police action to locate and capture the leaders of the incendiary Sons of Liberty as well as rumored arms stores. But the ill will between the colonists had boiled over and the New Englanders decided to take a stand. As the British set out, so did a number of night riders (Paul Revere is the only one anyone remembers) to alert the countryside. Companies of veterans and farmers had been in training for just such a day. Forewarned, they gathered in taverns across Massachusetts and beyond. That was only the first step, they then had to concentrate their forces and with no firm command structure or objective other than force the British to back down, their actions seemed overly brave and decidedly dangerous. Bottom line – these early Patriots (as seen by the colonists) or rebels (as seen by the English) were in 1775 exchanging fire in Lexington and Concord and igniting a conflagration that would not burn out for another eight years. How can one not want to know more about the circumstances that lay the groundwork for our nation?

Grant: What units are represented for each side and how do they compare to each other? Which side has the advantage with their units?

Bill: Units in Revolution Road are grouped into the historical military archetypes that participated in the battles. For the Patriot Revolutionaries, units include Leaders, Militia, Minutemen, and Field Cannon. The British Loyalist units include Leaders, British Regulars, Marines, Field Cannon, a fixed battery, and a Fleet. In From Boston to Concord, the British Regulars are more likely to inflict casualties then their Patriot militia and minutemen counterparts.

Militia units were citizen soldiers who had little training other than periodic drilling. Their effectiveness was generally not known until they actually saw battle. In Revolution Road, neither player initially knows how well militia will handle themselves. This is accomplished by using untried militia counters on the map board (they are printed with a question mark). Militia units that vary in strength are mixed up in an opaque container before the game starts. When an untried militia counter first sees combat, the ‘?’ counter is removed from the board and a randomly drawn militia unit that shows its effective strength replaces it.

Militia units were citizen soldiers who had little training other than periodic drilling. Their effectiveness was generally not known until they actually saw battle. In Revolution Road, neither player initially knows how well militia will handle themselves. This is accomplished by using untried militia counters on the map board (they are printed with a question mark). Militia units that vary in strength are mixed up in an opaque container before the game starts. When an untried militia counter first sees combat, the ‘?’ counter is removed from the board and a randomly drawn militia unit that shows its effective strength replaces it.

Minutemen units were well conditioned to act on a moment’s notice and frequently had battle experience from fighting in the French and Indian War. Minutemen have the special ability of quickly mustering when alerted by Nightriders and can also increase the effectiveness of the poorest militia units in combat.

British Regulars make up the majority of the British Loyalist force. Marines are also used in Bunker Hill and are slightly stronger than regulars.

British Regulars make up the majority of the British Loyalist force. Marines are also used in Bunker Hill and are slightly stronger than regulars.

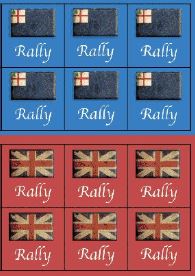

Leaders work similarly for both sides. British Loyalist leaders are better at rallying units than Patriot Revolutionary leaders but there are many more Patriot leaders than British leaders.

Grant: Can you give a little more detail on how Leaders work in the game and what benefit they offer? What Leaders are available?

John: As much as possible we tried to introduce historical leaders in the regions where they would have gathered and fought. Their influence in the game is not so much a combat role as a morale booster. Leaders rally troops by their mere presence. Of special  note is Dr. Joseph Warren, a highly respected colonial on both sides. Although forgotten today (He fell in the defense of “Bunker” Hill), had he survived those early days of the rebellion he might very well been a strong rival to George Washington for the hearts and minds of the young republic.

note is Dr. Joseph Warren, a highly respected colonial on both sides. Although forgotten today (He fell in the defense of “Bunker” Hill), had he survived those early days of the rebellion he might very well been a strong rival to George Washington for the hearts and minds of the young republic.

Grant: What are the Sons of Liberty and the Nightriders and how do they effect gameplay?

Bill: The Sons of Liberty were revolutionaries promoting a split from Great Britain. Two of the most prominent in New England were John Hancock and Samuel Adams. They both appear in From Boston to Concord and each are represented by a counter. It is the belief of many historians that General Gage’s orders for the ‘surprise’ expedition to confiscate rebel arms he believed were hidden in the town of Concord, also included an accompanying objective to find and capture Hancock and Adams and bring them back to Boston to stand trial for treason. One of the objectives for the British Loyalist player is to capture either or both men. If captured, the Patriot Revolutionary can perform escape attempts up until the time the captured patriots reach Boston or the game ends. Both Hancock and Adams are worth a nice chunk of victory points if they are in the hands of the British when the game ends.

Grant: What are Hidden Arms Markers and how are they used?

John: This was a clever mechanic introduced by Bill. Since the British were after arms  caches, we had to introduce them in such a way that would force the British to spend precious time searching towns along the way and to punish the British player if he doesn’t. To this end, we assigned a VP value to the major towns along the route. These are in effect Patriot points if they are ignored. The highest point value is found in Concord at the end of the march. If these VP caches are discovered they are denied to the Patriot player. So what would cause the British to search towns that have no such point value? Every action card has space on it for 0, 1, 2, or 3 hash marks. When the British search a town without a VP value they draw a card. If one or more hash marks are discovered, they translate into VPs for the British player.

caches, we had to introduce them in such a way that would force the British to spend precious time searching towns along the way and to punish the British player if he doesn’t. To this end, we assigned a VP value to the major towns along the route. These are in effect Patriot points if they are ignored. The highest point value is found in Concord at the end of the march. If these VP caches are discovered they are denied to the Patriot player. So what would cause the British to search towns that have no such point value? Every action card has space on it for 0, 1, 2, or 3 hash marks. When the British search a town without a VP value they draw a card. If one or more hash marks are discovered, they translate into VPs for the British player.

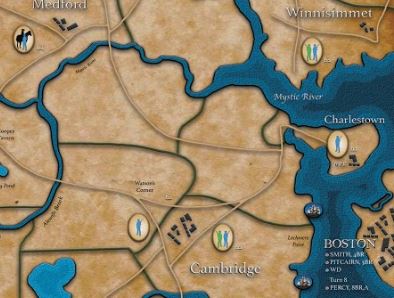

Grant: Please describe the game board and tell us what the different boxes are used for?

Bill: I started to speak to the maps back at question number five when you asked about challenges. There are no lack of maps covering Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill, but while doing research, finding two that agreed with each other made me begin to feel like Sisyphus. One map would have one thing, another map another. One map names something one way, another something else. Between finding more accurate features over time, play tests, and graphic style changes, if you asked me how many iterations of the maps I have made I could not honestly answer you other than to say an awful lot. When in doubt, I went with what the majority of sources had and if still unclear went with what the National Park service uses.

Both boards include game tracks for the turn, player actions, reserve actions and victory points. A space is provided for the draw deck and discards. The Bunker Hill board also has an area that tracks player morale and how much ammunition the Patriots have remaining. Each board has a section showing a list of actions available to each player.

The From Boston to Concord game board represents the countryside between Boston and Concord (imagine that), a distance of around 25 miles as the crow flies if I remember correctly. Area movement is used with the map being split up into regions that encompass several miles in area. Terrain features other than rivers and streams play no part in the game and are not featured. The most important feature on the map is the network of roads The British Loyalist player will tend to stick to the roads because it is

the quickest way to get from region to region. The Patriot Revolutionary player will attempt to set up hinderances along the key points to slow down the British player. Some regions on the board have icons that show gathering places where units muster and what units muster there, where hidden arms markers are located, and where off-board units enter. There is a legend on the board explaining the icons.

The Bunker Hill game board represents the Charlestown peninsula, the rivers bordering it, and a small sliver of Boston. Like From Boston to Concord, the map is split up into regions, but instead of measuring the regions in miles in Bunker Hill the region sizes are

measured in yards. Roads, which are so important in From Boston to Concord, are of only historical interest in Bunker Hill. Instead Bunker Hill is concerned with slopes, ridges, hilltops, staging areas and landing zones. There are Fleet Boxes used in conjunction with the British Fleet and that sliver of Boston mentioned is where the Copp’s Hill battery counter sits pestering the Patriots on the peninsula. There is also an off-board mustering area where Patriot reinforcements are placed before they arrive at Charlestown Neck on the north side of the peninsula. Depending on where the British Fleet is located, the arriving troops may be forced back to the mustering area by the ship’s cannon fire. Regions containing good defensive positions have the combat modifiers printed in them.

Grant: What is the Turn Sequence?

John: Both games follow this simple sequence:

- Draw Action Card

- Reset Action Tracks

- Alternate Performing Actions

- Counter and Marker Reset

- End of Turn

Although Boston to Concord has a Night Rider Action and no Sea Action while Bunker Hill has a Sea Action but no Night Rider Action.

Grant: What different type of cards are there and how are they used?

Bill: Cards are split along the diagonal with one side containing information for the British Loyalist player and the other side the Patriot Revolutionary player. During each game turn, players uses action points (which are kept track of on the action tracks) to perform actions. When the actions run out, the turn ends. The cards also are used to see if hidden arms are found or Sons of Liberty are captured. A card is drawn and the black oval in the center of each card is checked to see if any hash marks are in it which determines the success or failure of these actions.

Grant: How are Action Points obtained? What can they used for? What are Reserve Actions?

John: An Action card is drawn at the start of each turn. On it are found the number of actions allowable to each side that turn. Some cards reveal equal actions, some favor one side or the other by a single action.

The number and types of available actions vary from game to game and from the

standard game to the many solitaire variations. Actions include: Movement, Rally, Search, Volley Fire, Nightriders, Escape, Sniping, Charge, Assault, Artillery Fire, Sea Movement, Pass and Reserve Action. The Reserve Action is allowable only on a player’s final action each turn. Reserving an action allows a player to save one action to be played in a later turn. This offsets the occasional disparity in player actions. Up to two action points may be saved. Saved actions can be crucial.

Grant: Some actions are common to both sides but actions like Snipe, Assemble, etc. are unique to the Patriots. How do these asymmetric actions effect the game? Was this difficult to design?

Bill: The list of actions available to each player is perhaps my favorite part of Revolution Road. The tactics of the British and that of the Patriots were about as similar as the views of an optimist and a pessimist. Having player specific actions available along with common actions for both players is a mechanic that captures the differences between the sides simply and effectively.

An early design iteration had all the various possible actions players could take appearing on the cards. In order for the Patriots to Snipe, they needed a Snipe card. In order to move, they needed a Movement card. Each card showed an action the British player could use it for and an action the Patriot player could use it for. John and I found this both too restrictive and way too random. It also meant having a deck exclusive to each game. A ‘Search for Hidden Arms’ card action had no place in Bunker Hill. A ‘Move Fleet’ card action had no place in From Boston to Concord. After much thought, we realized we should make the actions that are available to the players completely independent from the cards. The cards would provide the action points and the actions would be chosen as needed by the player based on those usable by the player. We started anew forming a list of actions that are common to both players, exclusive to the British Player and exclusive to the Patriot player. The game suddenly became much more strategic and user driven as opposed to the player being restricted to the actions provided by random card draws. The beauty of this system is that it can easily be tailored to any battle by customizing the list of actions that are made available and the rules associated with those actions.

From this point on the ‘actions’ part of the game became easy to design. The hard part was in limiting the selection of actions available to the players. Over time the number of the actions grew considerably. If one of us read something that looked like it might be used as an action, in it went. There have been action purges and action population explosions aplenty (John and I have been at this a few years now).

Grant: How best is the Pass action used? What type of strategy options does this create?

John: First, a player may only pass if he has an equal number of actions or fewer actions available than his opponent. If a player has more actions – he must act. A player might pass and give the initiative to his opponent if he is not sure what to do or, as in chess, refrain from an attack simply to see what your opponent will do and then react to it.

Grant: How does combat work? How does retreat before combat work? Is the retreating side punished in any way?

Bill: Because of the scale of the two maps, combat is handled differently between the two games. In From Boston to Concord, opposing units may enter and remain in the same region. In Bunker Hill, the only time opposing units are allowed in the same region is during an Assault action and the conclusion of the assault will leave only one side in the region. In Bunker Hill, there is a Volley Fire action that allows ranged fire. Because of the size of the regions in From Boston to Concord, it has no Volley Fire action.

In both games, counters have a strength point value printed on the counter which represents the number of dice they roll in combat. British regulars have strength of 2, Marines a strength of 3. Minutemen have a strength of 1. Militia counters have a strength of 0, 1, or 2 the most prevalent being 1’s. Military counters have a functional side and a broken side. Leaders have a healthy side and a wounded side. Players apply hits that are scored against their units as they wish. A hit flips a counter to its broken or wounded  side. Broken units operate under limitations, the worse of which is that it does not contribute to the attack or defense in a battle. Another hit applied to a broken or wounded counter removes it from the game (this does not mean that all the men in the unit were killed or captured, it means the unit has lost any chance of regaining combat effectiveness). The Rally action allows leaders to flip a broken counter to its healthy side. There is no equivalent action for leaders; the only path a wounded leader counter can take is to death.

side. Broken units operate under limitations, the worse of which is that it does not contribute to the attack or defense in a battle. Another hit applied to a broken or wounded counter removes it from the game (this does not mean that all the men in the unit were killed or captured, it means the unit has lost any chance of regaining combat effectiveness). The Rally action allows leaders to flip a broken counter to its healthy side. There is no equivalent action for leaders; the only path a wounded leader counter can take is to death.

In Bunker Hill, retreat before combat is allowed only by the Patriot player during an Assault action taken by the British. Militia can only retreat if paired with a minuteman or leader.

In From Boston to Concord, retreat before combat can have more dire consequences. If defending units that have moved are attacked, the Patriot player better have minutemen or leaders present, or the militia involved will break or likely be lost. Because of the professional nature of the British units, consequences are less likely with a chance a unit might break.

Grant: How does the British Search Action work? What can they search for and why do they need to take this action?

John: I previously explained this, but boiled down, the British need to search for hidden arms because they need to deny the Patriot/Rebel player VPs and they may discover their own VPs along the way. In addition, if they can locate and capture either of the Sons of Liberty markers in Lexington they also gain big VPs. The process is simple. They declare a Search action in a town occupied by British Troops. If unoccupied by colonials their chances of discovery are very good. If colonial troops also occupy the region their chances of discover are decreased. In the case of Colonial VP regions, the result is based on a die roll that may be modified by defending colonial troops. In the case of non-colonial VP regions, the result is based on a card draw and the number of hash marks found thereon. Colonial defenders will reduce the value of the hash marks discovered so it behooves the British player to sweep the area clean before searching.

Grant: You created special rules to reflect 4 key events from the period. These are One if By Land, Two if by Sea, The Shot Heard ‘Round the World, Concord and Percy’s Reinforcements. What are these events and why are they important?

Bill: Here goes…

One if by Land, Two if by Sea:

In the old North Church in Boston a single lantern would be hung to warn revolutionaries if British Regulars were on the march leaving Boston from along the Boston Neck isthmus. Two lanterns would be hung if British Regulars were crossing the Charles River in boats. During the first turn of play, the British Loyalist player has the ability of landing units across the Charles River just as occurred historically. We also allow the British the option of choosing the land route or a combination of both. This way the player can play historically or experiment with a ‘what-if?’

The Shot Heard ‘Round the World:

The first shot fired at Lexington is considered by many the turning point that signaled the true start of the American Revolutionary War. Because of the ultimate importance and consequences triggered by that shot, it became known as the Shot Heard ‘Round the World. No one knows for certain which side fired it. What is known is that the British had no intention of starting a war when they marched. War was the last thing most British Loyalists wanted and if war did break out, neither the Patriots nor the British wanted to be the one blamed for starting it. The SHRTW rule takes all this into consideration. The SHRTW occurs when one player as the result of any action rolls a die or dice and scores the first hit in the game. If the Patriots trigger the SHRTW, the British receive a nice chunk of victory points and can start donkey-konging any Patriot units in their way indiscriminately. If the British trigger the SHRTW, it allows the Patriots to start using two very important actions in that arsenal that up until this time they were restricted from using: Snipe and Ambush. The early part of the game is therefore overshadowed by the players having to decide when and if it is best for them to trigger the SHRTW, or if there is a way for them to try to impel their opponent to do so.

Concord:

The Concord rule was placed in the game to reflect the end objective of the orders given to the marching troops; get to Concord and confiscate or destroy any hidden arms there. If the British do not get at least one unbroken British Regular to Concord by the end of the game, the Patriots win an automatic victory. When the British do reach Concord, the British player gets a chunk of victory points but at the same time the Smith/Pitcairn force (the troops that departed Boston) are the subject of several restrictions designed to reflect the fact that they have marched 25 miles with little rest, have diminishing ammunition, and are by now quite aware of the threat the gathering forces of Patriot militia represent.

Percy’s Reinforcements:

Early on Gage dispatched reinforcements under the command of Percy to assist Smith. Because of a comedy of errors, they were very late in getting underway. If enough units of the Percy force reach Lexington before game end, the British receive victory points, otherwise victory points are awarded to the Patriots. Victory points are also rewarded to the British if Smith/Pitcairn units make it back to Lexington joining up with Percy; points are awarded to the Patriot if they do not.

Grant: How is victory determined? What are conditional VPs awarded for?

John: Victory Points are awarded for the arms caches discovered or left undiscovered, for the elimination of infantry and artillery units, and for the random loss of broken units and wounded leaders at the end of a game. To this end a die is rolled for each broken unit and each wounded leader to see if the former is disbanded or the latter dies. This happens each time a “6” result is rolled. The Bunker Hill solitaire scenarios are scored based on British objectives achieved.

Grant: What are some of the Optional Rules included and why didn’t you add them to the base game?

Bill: Most of the optional rules serve to level the playing field between two players where one player has more experience with the game or simply where one player wants to create more of a challenge. For instance, in From Boston to Concord there is an optional rule that more realistically portrays the combat differences between militia and minutemen, but in so doing makes it slightly harder going for the Patriot player. In Bunker Hill, another optional rule affords the Patriot player more control on ammo expenditure. There is an optional rule that adds a ‘what-if’ option to Bunker Hill that allows the British player to use Landing Zones that were considered but not used historically. All the optional rules can be mixed or matched as long as players agree beforehand.

Grant: How long does From Boston to Concord take to play?

John: Once understood, approximately two hours.

Grant: We already talked about this earlier but I’m looking for a little more detail. The map changes for Bunker Hill. What is different between the two maps? What are the Hilltop Regions and how do they affect the game?

Grant: We already talked about this earlier but I’m looking for a little more detail. The map changes for Bunker Hill. What is different between the two maps? What are the Hilltop Regions and how do they affect the game?

Bill: I covered a lot of this above. The primary difference is in scale. The entire Bunker Hill map barely covers one section of one region found on the From Boston to Concord map. Bunker Hill includes elevations, including both Bunker Hill and Breed’s Hill. The roads appearing on its map are there for historical purposes only and serve no role in game play.

Grant: What terrain combat modifiers are there? What are the Charlestown Regions and Charlestown Neck?

John: There are no terrain combat modifiers in Boston to Concord but in Bunker Hill, there are hilltops, slope sides, defense-works and town regions that provide the defender with a bonus attack when assaulted and a bonus defense against volley fire. There are 10 Charlestown regions. Charlestown was the major port settlement on the peninsula and it served as a base for colonial sniping during the battle. The British were determined to burn it down and they largely succeeded using artillery hotshot. Charlestown Neck is the very narrow isthmus hat connects the Charlestown peninsula to the mainland. It was so narrow that some colonial units balked crossing it under British naval fire.

Grant: What is different about each side’s units in Bunker Hill?

Bill: The British have Marines, a slightly more powerful unit than British regulars and quite handy when attacking a defensive position. Both sides have field cannons. The British have a Fleet and Fixed Battery both of which can be used to bombard Patriot defenses and set Charlestown regions ablaze.

Grant: What does the Wrong Ammo/Ammo Arrives represent and how does it effect the scenario?

John: When the British landed on the Charlestown Peninsula they landed artillery with the wrong size ammunition and had to await the proper ammunition before it could be used. This is simulated by artillery that cannot be used for the first three turns of the game. Thereafter, a die is rolled hoping for a modified “6.” The die roll is increasingly modified each turn thereafter. This however does not affect naval fire, nor does it affect the battery located in Boston. Honestly, artillery plays as minor a role in the game as it did historically – in both games.

Grant: How does the British naval fleet work? How are landing areas used?

Bill: There are three Fleet Boxes on the board used to indicate the location of the Fleet counter. One Fleet Box is for the Charles River, one for Boston Harbor, and one for the Mystic River. Each Fleet Box commands a different field of fire over the Charlestown peninsula. The British have an action that moves the Fleet to an adjoining box and also that allows it to conduct bombardments. If the Fleet is in the Charles River, it has the added advantage of causing each Patriot reinforcement entering along the Charlestown Neck to possibly be retreated back from whence it came. This can greatly slow down reinforcements, but at the same time the Fleet may be of more use elsewhere supporting British landings.

The Charlestown Peninsula has six Landing Zones. These zones represent the historical landing sites the British used and also ones they considered using but didn’t. Arriving British units are placed in a Landing Zone. Based on the distance from Boston and the harassment the patriots could bring to the location, the number of units the British can land using the Land troops action varies for each zone.

Each Landing Zone has either one or two land regions associated with it called Staging Areas. Each Staging Area requires a certain number of units to be landed before any of them can be activated with a Move action. Again this varies by Landing Zone. Once the number of units has been reached, the restriction is lifted and any other units landed in the future can move inland with the next Move action regardless of the number of units in the region.

Grant: Are there new available actions for this scenario? What are they?

John: Yes, the Landing, Sea movement and Bombard actions are all unique to Bunker Hill. One unique aspect of our design is that the alternate landing sites considered at the time are included and may be used along with their corresponding difficulties.

Grant: Line of Site has been added to the rules governing the Bunker Hill scenario. How does this work and why is it in this scenario but not the other?

Bill: Thanks to our developer, Wade Hyett, the Line of Site rules are kept pretty simple and concise. Trust me when I say you would not have wanted to read any of the iterations John and I came up with explaining them. There are only three levels of elevation, sea, slope/ridge and hilltop. In a nutshell, higher elevations block the LOS from lower elevations. Units block LOS if at the same elevation. Charlestown regions block LOS on the peninsula. Regions that are adjacent always have a LOS between them.

Grant: How does Patriot ammunition work? How is it tracked? Why did you want to include this element?

John: It is plausible to suppose that if the Patriots had been fully supplied with all the ammunition they needed that they might have held out until the demoralized British retreated due to inordinate casualties. As it was, the Colonials were desperately short on ammunition and in the end this effectively broke their line…this and unrelenting British assaults.

In the game, Patriots lose an ammunition point anytime the Patriot player uses the Fire option. When this happens, the ammunition marker is advanced and his ammunition is reduced. When firing, the Patriot player determines if he is firing 1-2 units, at which point he retreats the marker 1 space, or more than 2 units at which point he retreats the marker two spaces. When the marker reaches the #16 space on the track, half his ammunition is gone and the Patriot player must subtract one from all his defensive position die rolls. He does not subtract 1 from his dice rolls when not in a defensive position. Units in one region may not split their fire against multiple regions. Sniping does not deplete ammunition. When the marker reaches the end of the Ammunition Track the marker is flipped to its DEPLETED side and the Patriots lose several advantages. When their ammunition is depleted Patriots may still fire but now subtract 2 from their die rolls. Patriot units lose their double hit defense ability and are now removed with a single hit. British units may now advance into their space and ENGAGE regardless of the unit odds.

In the game, Patriots lose an ammunition point anytime the Patriot player uses the Fire option. When this happens, the ammunition marker is advanced and his ammunition is reduced. When firing, the Patriot player determines if he is firing 1-2 units, at which point he retreats the marker 1 space, or more than 2 units at which point he retreats the marker two spaces. When the marker reaches the #16 space on the track, half his ammunition is gone and the Patriot player must subtract one from all his defensive position die rolls. He does not subtract 1 from his dice rolls when not in a defensive position. Units in one region may not split their fire against multiple regions. Sniping does not deplete ammunition. When the marker reaches the end of the Ammunition Track the marker is flipped to its DEPLETED side and the Patriots lose several advantages. When their ammunition is depleted Patriots may still fire but now subtract 2 from their die rolls. Patriot units lose their double hit defense ability and are now removed with a single hit. British units may now advance into their space and ENGAGE regardless of the unit odds.

Grant: How is victory determined?

John: Victory is determined much the same here as it is in Boston to Concord, except that here points are entirely based on casualties. The Solitaire versions add British objective point values based on the objectives achieved.

All in all, Revolution Road is a unique approach to Revolutionary War gaming, and for all of that it remains, simple, fast-playing and most of all, fun!

Thank you both John and Bill for your time and thoroughness in answering my many questions. After this interview, I am even more resolved to add Revolution Road to my collection. I will have to say it appears that you have a winner here that looks historically accurate, yet playable, and most importantly, looks like it will be a lot of fun!

If you are interested in pre-ordering Revolution Road, please visit the game page on Compass Games website at the following link: https://www.compassgames.com/preorders/revolution-road.html

The game is expected to be complete and ready for the public in July 2017, just in time for Independence Day!

-Grant

Pre-ordered today based on the nice article.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading. The game definitely looks good and to make it even better it is 2 games in one. Bonus.

LikeLike

Can’t wait to pick this one up and I only live about 20 minutes from Compass Games!

LikeLike

I had pre-ordered this game. I only hope the game is not as riddled with historic inaccuracies as this interview was.

LikeLike

Grant another great interview and again you have inspired me to purchase another game!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. I will tell you that there are actually two games in that box with one being the Revere Ride and the other being Bunker Hill. Bunker Hill is a real hex and counter wargame and is quite good. The Revere Ride is good fun but more CDG type game with the movement of counters in areas. Enjoy!

LikeLike